Translate this page into:

Abdominal Pain in a Female with Lupus – Opening the Pandora’s Box

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Mohanasundaram S, Samuel MK, Kurien AA. Abdominal Pain in a Female with Lupus – Opening the Pandora’s Box. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:181–4. doi: 10.4103/ijn.ijn_316_22

Abstract

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that can involve multiple organ systems. The most common form of vasculitis seen in SLE is small vessel vasculitis. Aortitis in SLE or antiphospholipid syndrome is an extremely rare complication. Here, we present a 32-year-old female who presented with a history of prolonged abdominal pain, who was evaluated and diagnosed to have aortitis as an unusual involvement in SLE with secondary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Keywords

Abdominal pain

aortitis

autoimmune

lupus

vasculitis

Introduction

The prevalence of vasculitis in systematic lupus erythematosus (SLE) varies between 11% and 36%, of which small vessel vasculitis is the most common manifestation.1 Aortitis, similar to that seen in Takayasu arteritis, is a rare complication in SLE. Treatment remains a great challenge, which includes titrating immunosuppressants and managing complications. Here, we present a young female who presented with abdominal pain for 1 month.

Case Report

A 32-year-old lady presented with complaints of vague abdominal pain, not localized to any particular quadrant, intermittently present for 1 month and aggravated over the last 4 days. Over the past month, the abdominal pain was associated with vomiting and occasional loose stools, which subsided with symptomatic management. There was no specific aggravating or relieving factor for the abdominal pain, nor was it associated with food intake or defecation. A presumptive diagnosis of subacute appendicitis was made, and a nephrology opinion was sought for incidentally detected albuminuria.

Evaluation revealed that she had the sensation of abdominal bloating and had passed black tarry sticky stools in the last 2 days. She had complaints of swelling in both feet, noticed over the last 3 days. She did not have fever, dysuria, or high-colored urine. She denied taking over-the-counter medications. Her past history was significant for four spontaneous abortions and one healthy child delivered normally without any gestational complications. She had also been treated for hypertension for the past 4 months.

Clinical examination showed pallor, facial puffiness, and pitting pedal edema. Her blood pressure was 110/80 mmHg, with pulse rate 98 bpm, without any special characteristics, felt equally in all peripheral vessels, and no radio-radial or radiofemoral delay. Her temperature was 99°F. Examination of the abdomen revealed diffuse tenderness, yet more in the right iliac fossa, without rebound tenderness, guarding, or rigidity, which might have led to the initial working diagnosis of subacute appendicitis. There was no renal bruit, and the fundus examination was unremarkable.

Her laboratory investigations revealed 3+ albuminuria and 2+ blood in urine dipstick. On 24 h quantification, she had proteinuria of 2.84 g/day. Complete blood count showed hemoglobin of 10.2 g %, total leukocyte count 7400 cells/mm3 with differential count being 73% neutrophils, 15% lymphocytes, and 12% monocytes, and platelet count 35,000/mm3. Peripheral smear study showed normochromic, normocytic anemia, adequate white blood cells, and thrombocytopenia. In view of suspected subacute appendicitis, she was initiated on intravenous antibiotics. Since urinalysis showed evidence of glomerular involvement, we sent for serum complements C3 and C4 levels to look for evidence of infection-related glomerulonephritis. Considering her significant past history of abortions, we evaluated her anti-nuclear antibody, anti-double-stranded DNA antibody, anti-smith antibody and anti-phospholipid antibody profile. She had low C3 (34.90 mg/dL [ref.: 82–160 mg/dL]) and C4 (8.0 mg/dL [ref.:10–40 mg/dL]) levels. The Anti-nuclear antibody titer was 1:80 positive, anti-double stranded DNA antibody was 18 U/mL, and anti-Smith antibody was found to be 100 U/mL, suggesting the presence of SLE. She also had high titers of lupus anticoagulant (57.00 U/mL [ref.: 33–41.0 U/mL]) and anti-β2 microglobulin (9737 U/mL [ref.: 609–2366 U/mL]), thus leading to the diagnosis of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) secondary to SLE [Tables 1 and 2].

| Laboratory investigations | Reference values | On admission | On day 3 | On day 9 | On day 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinalysis | 3+ albumin 2+ blood |

3+ albumin 2+ blood |

|||

| 24-h urine protein (mg/day) | <150 | 2840 | |||

| Random blood sugar (mg/dL) | 70-100 | 137 | 118 | 124 | 113 |

| Blood urea (mg/dL) | 8-21 | 22 | 23 | 32 | 27 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8-1.3 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 135-145 | 136 | 144 | 142 | 136 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 3.5-5.0 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.6 |

| Serum chloride (mEq/L) | 98-106 | 101 | 101 | 98 | 104 |

| Serum bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 23-28 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 24 |

| Complete blood count: | |||||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.0-16.0 | 10.2 | 10.6 | 10.2 | 9.9 |

| Total leukocyte count (per µL) | 4500-11,000 | 7400 | 6000 | 4300 | 5100 |

| Differential leukocyte count (%) | |||||

| Neutrophils | 40-70 | 73 | 74 | 69 | 72 |

| Lymphocytes | 22-44 | 15 | 16 | 20 | 16 |

| Eosinophils | 4-11 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 12 |

| Monocytes | 0-8 | - | - | - | - |

| Basophils | 0-3 | - | - | - | - |

| Platelet count (per µL) | 150,000-400,000 | 35,000 | 30,000 | 61,000 | 126,000 |

| Investigations | Reference values | Patient’s values |

|---|---|---|

| Serum complements | ||

| C3 (mg/dL) | 82-160 | 34.90 |

| C4 (mg/dL) | 10-40 | 8.00 |

| Serum C-reactive protein | <5 mg/dL | 27 |

| Autoimmune profile: | ||

| ANA | <1:80 | 1:80 |

| dsDNA (U/mL) | <6 | 18.0 |

| Anti-Sm/RNP (U/mL) | <6 | 100.0 |

| (Anti-Smith/anti-ribonucleoprotein) | ||

| Anticardiolipin antibody | ||

| IgM (U/mL) | <12.5 | 11.8 |

| IgG (U/mL) | <15 | 13.2 |

| Lupus anticoagulant (U/mL) | 33-41.10 | 57.00 |

| Anti-β2 microglobulin (U/mL) | 609-2366 | 9737 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 11-13.5 | 19 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (s) | 21-35 | 42 |

| INR | <1.1 | 1.5 |

INR=International normalized ratio, Sm/RNP=anti-Smith/anti- ribonuceloprotein, ANA: Antinuclear antibody, dsDNA: double-stranded DNA, RNP: ribonucleoprotein.

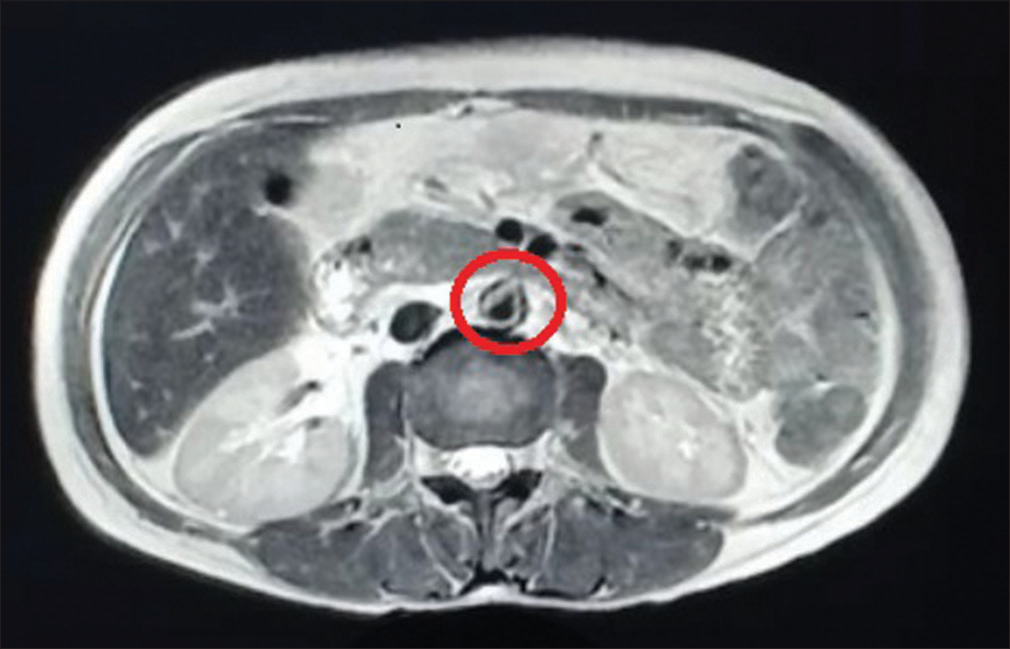

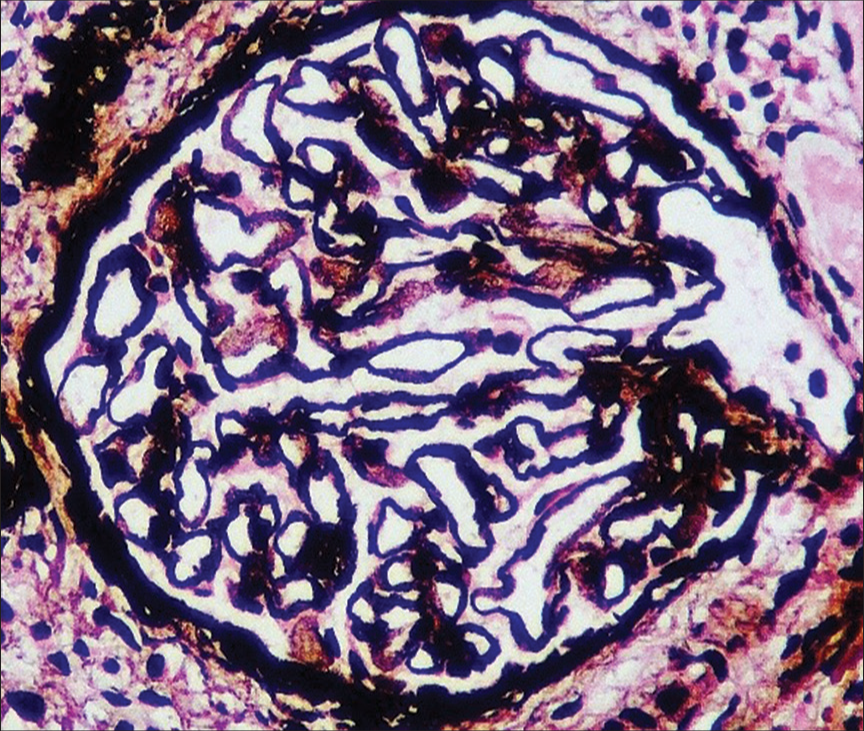

Given active lupus nephritis, we initiated the patient on low-dose steroids (prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/day) under the coverage of antibiotics for a period of 5 days, till the culture reports of stool, urine, and blood showed no microbial growth. Her platelet count improved with the continuation of steroids from 30,000 to 126,000 cells/mm3 over 15 days. Ultrasonography revealed splenomegaly and minimal free fluid. We suspected a vascular etiology and performed magnetic resonance angiography which revealed asymmetric thickening (2–4 mm) along with irregular enhancement of the walls of the aorta, suggesting aortitis, without the involvement of its branches [Figure 1]. With low-dose steroids, her abdominal pain subsided. On improvement of thrombocytopenia and normal coagulation profile, a renal biopsy was done, which showed 18 glomeruli; of these, two glomeruli were globally sclerotic and one was segmentally sclerosed. There was a mild increase in mesangial cellularity. Capillary lumen was patent. Pinhole lesions and early spikes were seen on the glomerular basement membrane. No wire-loop lesion or hyaline thrombus or fibrinoid necrosis was seen. There was no interstitial fibrosis or tubular atrophy. Blood vessels were unremarkable. On immunofluorescence, IgG (+3), IgM (+1), IgA (+1), C3 (+2), and C1q (+2) were positive on the capillary loops and mesangium. IgG and C1q were positive on the tubular basement membrane as well. There was no light chain restriction [Figures 2 and 3]. The activity index was 1/24, and the chronicity index was 1/12. Hence, the histological diagnosis of lupus nephritis – class V (according to the International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society classification) was made.

- Magnetic resonance angiography revealing asymmetric thickening (circled) along with irregular enhancement of the walls of the aorta at places, features suggestive of aortitis.

- Renal biopsy showing early spikes and pinhole in the glomerular basement membrane (periodic acid Schiff-silver stain, ×400).

- Renal biopsy showing IgG (+3) in glomerular capillary wall, mesangium, and tubular basement membrane (immunofluorescence IgG stain, ×400).

In the presence of subnephrotic range proteinuria (2.84 g/day) in secondary membranous nephropathy with minimal activity index, she was advised salt restriction, low-dose steroids (prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg/day), tablet enalapril 5 mg twice a day, tablet aspirin 75 mg/day, and tablet hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/day. She was counseled regarding the prerequisites before future conception. She is currently under biochemical and immunological remission with normal functioning kidneys and is on an outpatient basis follow-up for the past 10 months.

Discussion

The spectrum of vasculitis in SLE is broad due to the inflammatory milieu affecting the vasculature of all sizes. However, aortitis is an extremely uncommon occurrence. Without intensification of immunosuppression, aortitis can be life-threatening.2

Clinically, aortitis presents with nonspecific symptoms such as fever, weight loss, easy fatiguability, abdominal pain, or low backache. In cases where it is associated with thromboembolic manifestations, patients present with chest pain or intermittent claudication.3

There are a few case reports describing heterogeneous presentations such as aortic thrombus and aortic dissection in patients with aortitis secondary to SLE. Also, the aorta being a major blood vessel, histopathologic confirmation in these case reports has not been done. Hence, diagnosis is generally established using imaging techniques such as computed tomography with angiogram, magnetic resonance imaging angiography, or positron emission tomography.4

Most case reports in the literature have described aortitis commonly in men, in the ascending aorta. The presence of aortitis, associated with high levels of C-reactive protein (range: 21.4–33.7 mg/dL) and positivity of anti-DNA occurred mostly in the absence of major organ involvement, unlike our patient who had lupus nephritis.5-7

This patient had associated APS, which could be possibly secondary to antibodies against the vasculature in the inflammatory milieu and makes our case unique.8

There has been an association between long-term steroids in the pathogenesis of aortic aneurysms and dissections, due to histologic changes in the tunica media of blood vessels. Paradoxically, low doses of steroids cause adequate improvement in symptoms and radiological findings.9 The presence of catastrophic APS (CAPS) or severe activity in renal biopsy would warrant rituximab or plasmapheresis.10 Since our patient presented with mild activity in renal biopsy and subnephrotic range proteinuria, she was treated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, hydroxychloroquine and low-dose steroids to keep the inflammation under control. She is currently asymptomatic and is under follow-up on an outpatient basis.

Conclusion

Aortitis in SLE with secondary aPLA syndrome is a very rare complication. Considering the rarity, there has been no clear evidence on management of these patients. Currently, the dose of glucocorticoids is controversial. Further studies are needed regarding the different treatment protocols, in order to propose better therapeutic management.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2014;16:440.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupus aortitis: A fatal, inflammatory cardiovascular complication in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2020;29:1652-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aortic vasculitis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Reumatol Clin. 2016;12:169-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aortitis: Imaging spectrum of the infectious and inflammatory conditions of the aorta. Radiographics. 2011;31:435-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large artery inflammation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2013;22:953-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aortitis and aortic thrombus in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2006;15:541-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathologic quiz case: An unusual complication of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:324-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupus aortitis: A case report and review of the literature. J La State Med Soc. 1996;148:55-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lupus aortitis successfully treated with moderate-dose glucocorticoids: A case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2020;59:2789-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aortitis in the setting of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2020;29:1126-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]