Translate this page into:

Watermelon stomach in end-stage renal disease patient

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), also called watermelon stomach, is a rare cause of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. GAVE is associated with a number of conditions, including portal hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and collagen vascular diseases, especially scleroderma. Limited reports of GAVE are present in CKD patients. Argon plasma coagulation (APC) is an effective therapy for GAVE. We describe the case of a CKD, stage V patient, who presented with recurrent blood loss in stools and transfusion-dependent anemia. Her endoscopy revealed GAVE, which was managed uneventfully with APC.

Keywords

Chronic kidney disease

gastric antral vascular ectasia

watermelon stomach

Introduction

GAVE a rare cause of upper GI bleed has prominent associations with autoimmune disorders and liver cirrhosis. We report a case of Chronic kidney disease stage 5 with Chronic liver disease who presented with blood loss anemia and was found to have vascular ectasia involving both the antrum and duodenum. She was treated successfully with Argon Plasma coagulation.

Case Report

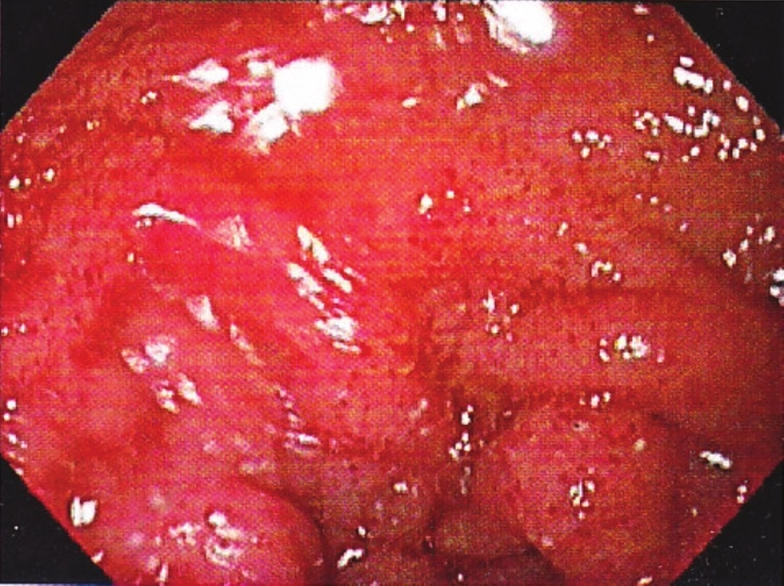

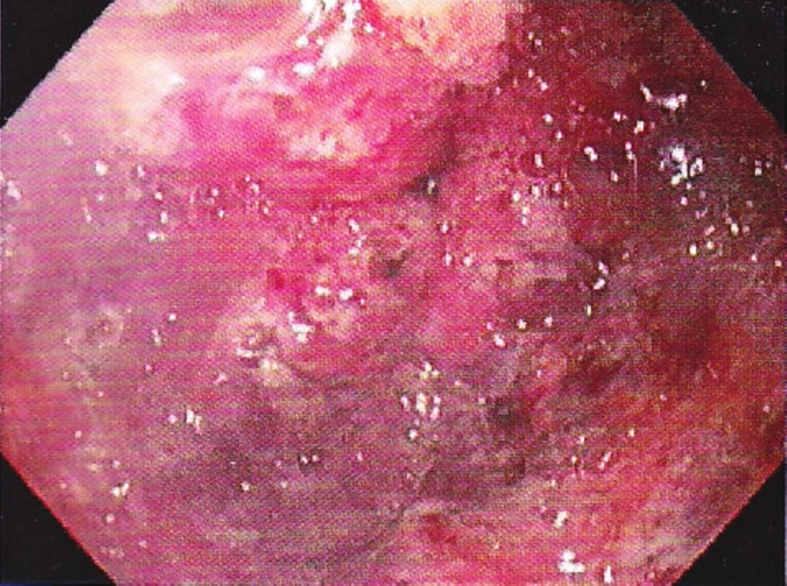

A middle-aged woman, a known case of hypertension and stage V chronic kidney disease (CKD) since 10 years, and on maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) for 6 years, presented with complaints of blood in the stools since the past 8 months, and abdominal distention and discomfort since the past 2 months. She was diagnosed with chronic liver disease (CLD) related to hepatitis C virus (HCV) 8 months back. As a result of continuous loss of blood in the stools, the patient had developed severe anemia, for which she had received multiple blood transfusions during the past 8 months. On examination, her BP was 160/70 mmHg and PR 106/min, and she had severe pallor. An abdominal examination revealed free fluid with no organomegaly, whereas the other systems were unremarkable. Her laboratory investigations revealed severe iron-deficiency anemia with hemoglobin of 4.3 gm/dl. Her HCV genotype was one with the RNA copies of 8.5 × 106 IU/ml. Ascitic fluid analysis revealed high serum-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG). Ultrasonography (USG) of her abdomen was suggestive of CLD with cirrhotic changes, with normal portal vein and bilateral contracted kidneys, without any organomegaly. The hepatic venous pressure gradient was 5 mmHg. During her hospital stay, she was given hemodialysis along with blood transfusion and intravenous (IV) iron in view of the severe iron deficiency. As she had melena, she was taken for upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and colonoscopy, where she was found to have multiple linear gastric vascular malformations in the antrum, compatible with gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), with spurt oozing [Figure 1]. There were also ectasias in the cardia and the duodenum [Figure 2]. There were no esophageal varices. Argon plasma coagulation (APC) was done for GAVE to which she responded well [Figure 3]. Her colonoscopy was normal. Subsequently the altered blood in stools decreased, her blood transfusion requirement decreased, and she was discharged on a conservative line of management.

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia

- Duodenal vascular ectasia

- Antrum post APC

Discussion

Although previously reported in the literature, GAVE or watermelon stomach was first described definitively by Jabbari et al.[1] Although known to be associated with a number of conditions like cirrhosis, CKD, collagen vascular diseases and pernicious anemia, the exact etiopathogenesis of GAVE remains unknown.[2] The most common reported association is with autoimmune disorders, whereas cirrhosis accounts for 30% of the condition in these patients.[3] The incidence of GAVE in CKD is unknown, with few relevant publications in the literature.[4]

Our case was interesting as incidentally the patient had both CKD and CLD, both of which are associated with GAVE. However, as the history of CKD was of 10 years, whereas HCV-related CLD was recently diagnosed, the possibility of CKD-associated GAVE was more likely. Moreover, her USG revealed a normal portal vein, with a normal size cirrhotic liver. Absence of portal hypertension ruled out the possibility of portal hypertensive gastropathy, which has an endoscopic appearance similar to that of GAVE.[5] Besides the antrum, the patient also had vascular ectasias affecting the first part of the duodenum. There are reports of duodenal vascular ectasia in association with GAVE, even in patients with a normal antrum.[6]

The treatment modalities for GAVE include pharmacological, surgical, and endoscopic therapies. Pharmacological treatments with documented efficacy are tranexamic acid, estrogen–progesterone therapy, especially in renal failure,[7] and octreotide injections. However, these are mainly case reports or small case series. Even as surgical antrectomy provides the most definitive therapy for GAVE, it is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

Various endoscopic treatments have been described to manage GAVE, including Neodymium: yttrium–aluminum garnet (Nd: YAG) laser, APC, and a heater probe. Of these, APC is the most frequently used endoscopic treatment, as it is easier and safer to use, with limited depth of penetration and a tendency for the ionized electric arc to deflect away from the coagulated tissue to the surrounding mucosa.[8]

The number of sessions needed to eradicate GAVE depends on the pattern, extent, and number of lesions. In our case, the patient was managed effectively with APC in a single session, with a decline in gastric blood loss and requirement of blood transfusion.

To conclude, GAVE is a rare cause of persistent GI blood loss, with a known association with CKD. Presenting as transfusion-dependent anemia, it can be effectively eradicated by endoscopic therapies, especially APC, as in our case.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia: The watermelon stomach. Gastroenterology. 1984;37:1165-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia successfully controlled by argon plasma coagulation. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2007;36:702-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;47:e77-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gastric antral vascular ectasia in cirrhotic patients: Absence of relation with portal hypertension. Gut. 1999;44:739-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Massive gastro-intestinal haemorrhage due to vascular ectasia of the duodenum. A case report. S Afr J Surg. 1992;30:111-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Watermelon stomach. An unusual cause of recurrent upper GI tract bleeding in the uraemic patient: Efficient treatment with oestrogen-progesterone therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:871-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review article: Current therapeutic options for gastric antral vascular ectasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:157-65.

- [Google Scholar]