Translate this page into:

Emphysematous pyelonephritis: A single center study

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

We present our experience of 22 cases of emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) treated from 1996 to 2012. Medical records were analyzed retrospectively for demographic profile, presence and duration of diabetes mellitus, and mode of clinical presentation. EPN was diagnosed based on demonstration of intra-renal gas by plain X-ray, ultrasound, and/or computed tomography (CT) scan. Details of medical treatment, reason for surgical intervention, and final outcome were recorded. Univariate analysis was performed to identify risk factors for mortality and P value of less than 0.05 was taken as significant. Twenty-two cases (6 males, 16 females) of EPN were diagnosed. Seven cases presented with acute pyelonephritis, seven cases with urosepsis, and the remaining eight patients with multi-organ dysfunction. CT grading of EPN was class IV in three, class III in four, class II in 14, and class I in one. All were initially managed medically with parenteral antibiotics. Ten patients needed additional surgical intervention. The overall survival rate was 86.3% (19/22). Among the risk factors analyzed higher CT grade, altered sensorium and thrombocytopenia were significantly associated with mortality. We conclude that a more conservative approach in managing EPN has become the standard of care. Patients having high CT grade of lesions (III and IV) with altered sensorium and thrombocytopenia at presentation are more likely to die due to the disease and may be better managed by an aggressive surgical plan.

Keywords

Diabetes

emphysematous pyelonephritis

outcome

Introduction

Emphysematous pyelonephritis (EPN) is a rare but potentially life-threatening necrotizing renal parenchymal infection characterized by the production of intra-parenchymal gas. Till mid-1980s, the standard treatment was nephrectomy of the affected kidney because efforts in preserving the kidney by non-surgical treatment led to mortality of upto 60-80%.[1] The situation has improved dramatically in the last two decades with earlier computed tomography (CT) scan based diagnosis and advances in multi-disciplinary intensive care of sepsis syndrome and multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) with the overall mortality estimated to be 20%[1] to 25%.[2] We present our experience of 22 cases of EPN treated between 1996 and 2012 at a tertiary care hospital in South India.

Materials and Methods

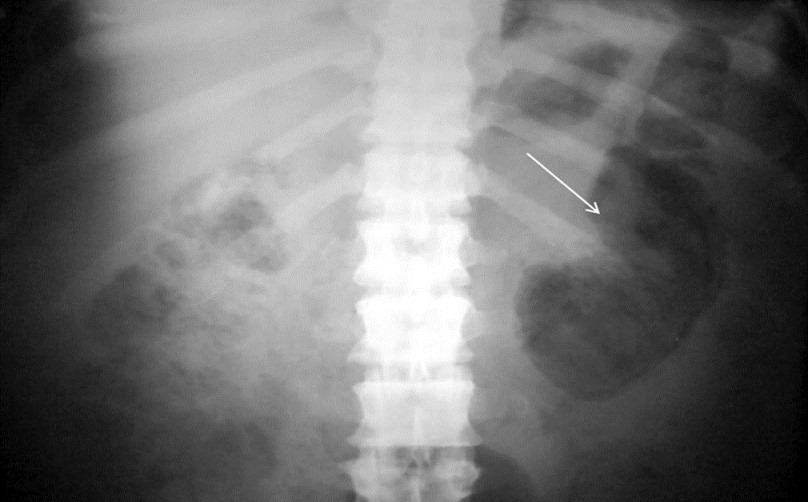

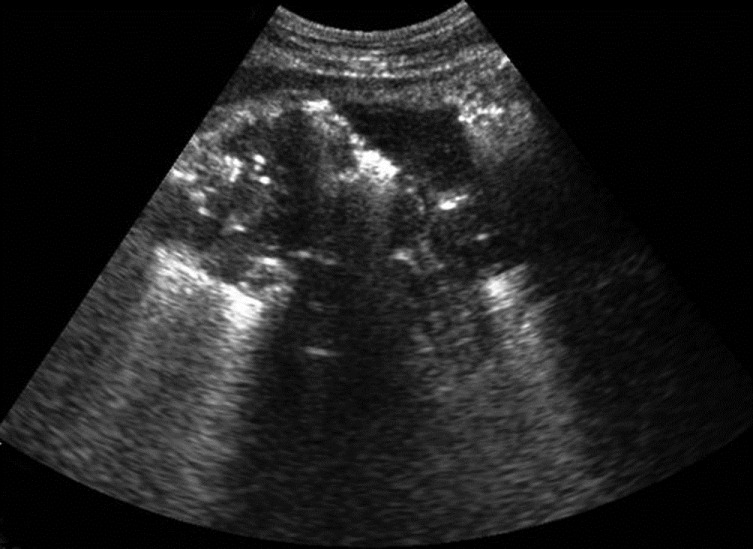

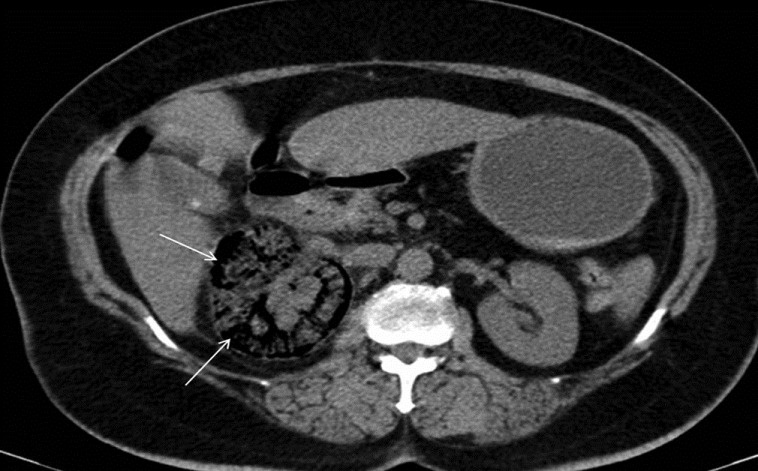

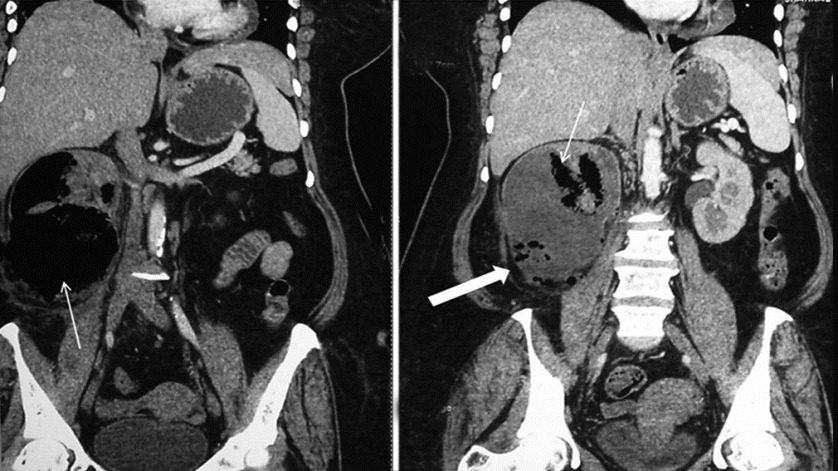

We retrospectively analyzed the medical records of 22 consecutive cases of emphysematous pyelonephritis admitted between 1996 and 2012 for demographic data, clinical and laboratory profile, and outcome. The presence and duration of diabetes mellitus (DM) and the level of glycemic control were noted. The hemodynamic status and the level of consciousness at initial presentation, renal function, and other biochemical parameters were recorded. Initial diagnosis was recorded as acute pyelonephritis (APN), urosepsis, or multi-organ dysfunction syndrome. APN was diagnosed by the triad of fever, dysuria, and loin pain. Urosepsis was defined as bacteriological evidence of urinary tract infection, pyuria with markers of sepsis syndrome, and MODS was defined as clinical or biochemical markers of dysfunction of two or more organ systems in the presence of sepsis syndrome. Acute renal function impairment was defined as persistent elevation of the serum creatinine level of more than 0.3 mg/dl from the baseline or first serum level at the time of admission, after volume resuscitation and excluding significant obstruction. Blood and urine microbiology reports were reviewed. The diagnosis of EPN was initially suspected on abdominal X-ray [Figures 1 and 2] and ultrasonography of the abdomen [Figure 3], which was later confirmed by computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen [Figures 4-6]. Cases were classified into four classes based on CT findings, as described by Huang and Tseng.[3] Class I – gas in ureter/pelvicalyceal system; Class II – gas in renal parenchyma; Class III – gas in renal parenchyma extending beyond the fascia to perinephric (IIIa/pararenal spaces IIIb); and Class IV – bilateral EPN or EPN in solitary kidney.

- Abdominal X - ray showing extensive reniform gas within renal parenchyma

- Abdominal X-ray showing extensive gas with paranephric spread to thigh

- Gas detected on ultrasonography in right kidney as multiple echogenic foci giving distal dirty acoustic shadows

- Non-contrast CT demonstrating gas accumulation limited to the right kidney parenchyma without perinephric extension (emphysematous pyelonephritis class II)

- Non-contrast CT (reformatted coronal) showing gas in the right renal parenchyma extending into perinephric space (emphysematous pyelonephritis class IIIa) (arrows)

- Non-contrast CT (reformatted coronal) showing right - sided (emphysematous pyelonephritis class IIIb) with extension of gas to the perinephric space and in to thigh muscle (arrows)

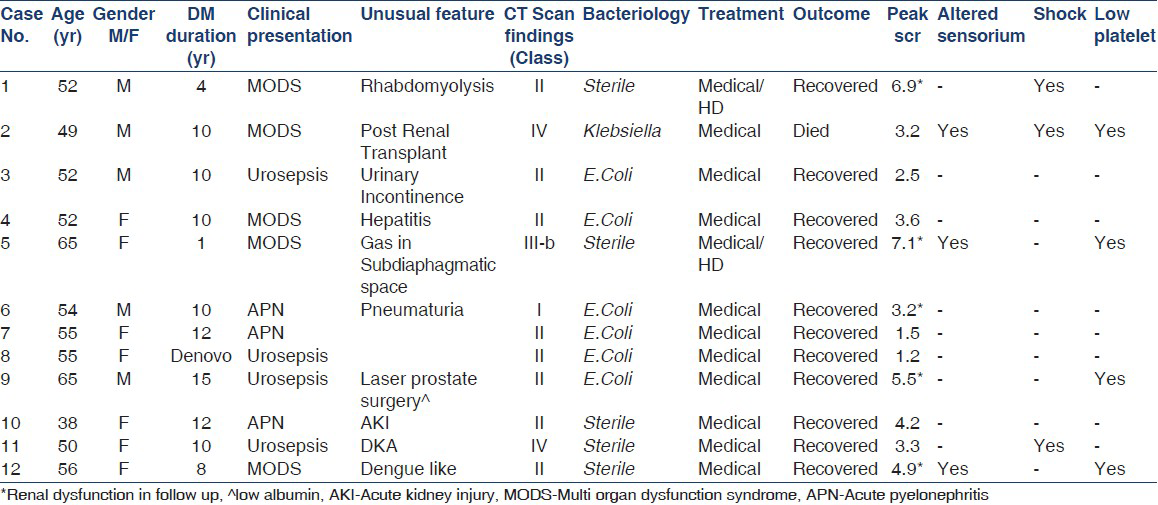

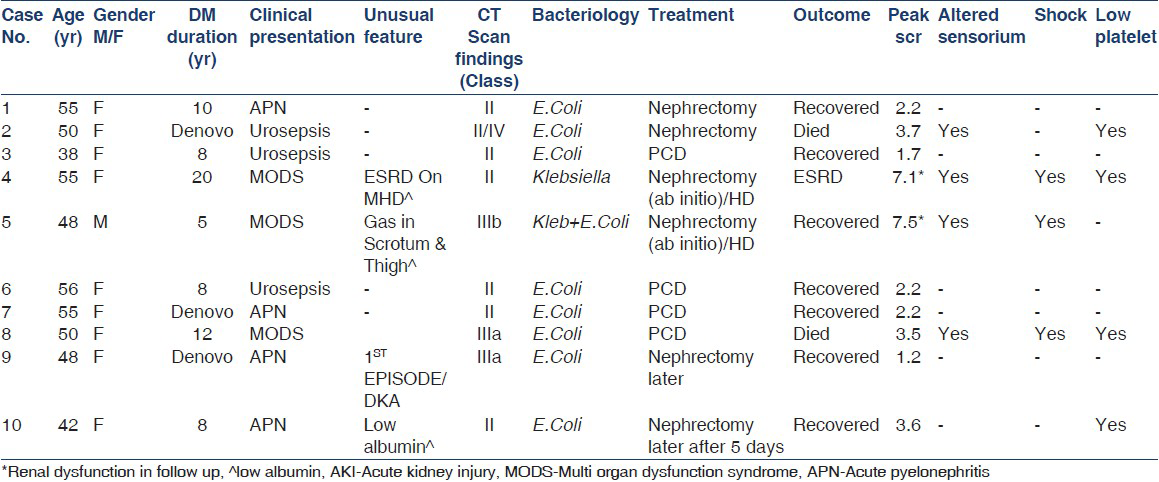

We analyzed the differences in clinical features, management, and outcome among the different classes of EPN. All patients were treated by the multi-disciplinary team comprising of Nephrologist, Urologist, Endocrinologist, and Intensivist. All patients required aggressive fluid resuscitation, hemodynamic support, and insulin infusion for glycemic control. Empirical antibiotics with third-generation cephalosporin or piperacillin + tazobactum along with aminoglycoside dose modified for renal dysfunction were started in all patients and subsequent changes made as required based on urine culture sensitivity results. Surgical approach involved nephrectomy or drainage of intra or perirenal abscess by percutaneous technique (PCD). Risk factors such as thrombocytopenia, acute renal insufficiency, altered mental status, and shock at presentation influenced decisions regarding early or deferred surgical intervention. Dialysis was instituted based on clinical and biochemical indications (S creatinine >5 mg%). Clinical and laboratory details of these cases managed medically and surgically have been tabulated [Tables 1 and 2]. Relevant tests of significance for comparison of means between groups were applied (t-test/Chi-square test) and P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Univariate analysis was performed using 11 possible predictors to identify risk factors for mortality namely: Age (<50 years vs. ≥50 years), sex (male vs. female), diabetes (<5 years vs. ≥5 years), presentation categories (acute pyelonephritis, urosepsis, multi-organ dysfunction), CT Grade (II/III/IV), culture positive vs. negative, serum creatinine (peak value), altered sensorium (absent vs. present), shock (absent vs. present), platelets (normal vs. thrombocytopenia less than 1 lakh/ml), and treatment (medical vs. surgical). Online statistical logistic regression package was used from http://statpages.org/logistic.html and P value of less than 0.05 was taken as significant. Variables were categorized before analysis.

Results

A total of twenty-two cases of EPN were diagnosed during the study period (16 females and 6 males). Eighteen patients had pre-existing diabetes mellitus and rest was diagnosed at presentation to have DM. The median duration of DM was 9 years (range: 0-20 years). Glycemic control was poor in all the cases with pre-existing DM (HbA1c >7%). EPN was left sided in 12 patients, right sided in 7, and bilateral in 3 (one renal transplant allograft).

Seven patients presented with acute pyelonephritis (APN), seven with urosepsis, and eight with MODS. Patients were classified according to CT scan findings. EPN class I (one case) presented with APN and pneumaturia, whereas in EPN class II (14 cases), five cases presented as APN, four as MODS, and five with urosepsis. In EPN class III (four cases), three patients presented with MODS and one with APN, whereas in EPN class IV (three cases: Bilateral in two and renal allograft in one case), two presented with urosepsis and one with MODS.

E. coli (14/17) and Klebsiella (2/17) were the most common organisms identified on urine culture. One patient was co-infected with both the organisms and cultures were sterile in five cases. Of the three patients who died, two underwent surgical procedures (one of EPN class II and other of EPN class III) and one, who was post-renal transplant, was managed conservatively (EPN class IV) due to poor clinical status even though deferred surgical intervention was contemplated.

The overall survival rate in our series was 86.3% (19/22). Twelve cases were managed with antibiotics alone (Medical group, Table 1) and 10 required surgical management [Table 2]. Mean age and duration of DM were 53.6 years and 8.5 years in medical group and 49.7 years and 7.1 years in surgical group, respectively (P value = 0.3 and 0.53, respectively). The mortality of the patients treated with antibiotics alone was 1/12 (8.3%) and 2/10 (20%) in those requiring surgical management. Surgical treatment was offered ab-initio in two patients due to extensive local disease in the presence of high-risk factors and subsequently in eight patients who did not respond appropriately to medical management alone.

Indications for delayed surgical management were significantly renal or perirenal collections with rising serum creatinine, and uncontrolled sepsis after 72 h of medical treatment. The success rate of management by percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) combined with antibiotic treatment was 75% (3/4). Six patients underwent nephrectomy (open nephrectomy) and all of them survived.

Of the 11 parameters analyzed, CT grade (Chi-Square: 8.2603, P = 0.0041), altered sensorium (Chi-Square: 7.9648, P = 0.0048) and thrombocytopenia (Chi-Square: 6.9405, P = 0.0084) were associated with mortality.

Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <1,00,000/μl) was noted in eight cases (four med/four surgical) but was not life-threatening. Shock was noted at initial presentation in six patients and altered sensorium in seven. All three patients having shock, thrombocytopenia, and altered sensorium together died. Low albumin was noted in three patients with underlying diabetic nephropathy and was not associated with mortality.

There was complete recovery of renal function in 15 cases (S. creatinine <1.5 mg/dl), 6 developed chronic kidney disease (CKD) one with EPN class I, three with EPN class II, and two with EPN class III) and one patient went on to develop end-stage renal failure (EPN class II) requiring maintenance hemodialysis. Out of the total, 20 patients had non-oliguric acute kidney injury and five out of them required dialysis before recovery.

Discussion

In this series of 22 cases of EPN treated by a multi-disciplinary management team with a standard protocol, 19 (86.3%) survived the illness, with seven of them having residual CKD. Eight patients presented with MODS and only 2 of them died, whereas one patient out of seven in urosepsis group died. None of the patients in group with classical APN died. In our series, the outcome/prognosis correlated more with higher CT grade (III/IV) of classification than the mode of presentation of EPN (CT grade Chi-Square: 8.2603, P = 0.0041).

All 22 cases were initially managed medically with broad spectrum parenteral antibiotic. Ten out of 22 cases went on to need surgical intervention (percutaneous drainage of the abscess needed in 4 cases and nephrectomy in six cases). Indication for surgical intervention included extensive disease (two patients) and or failure to improve medical treatment (eight patients). These two groups were similar in age of the patients and their duration of DM (P = 0.3 and 0.53, respectively). Three patients died (one in 12 medically and two in 10 surgically treated). We had patients having predominant left-sided involvement (54.5%) as in other series (67%[3] and 60%).[4] Bilateral disease was uncommon (3 of 22) in our series too. All our patients had poor glycemic control at presentation. Duration of DM was similar in the patients who underwent nephrectomy than those who were managed medically or by PCD (7.2 years vs. 8.5 years and 7 years, respectively). Recovery in two of the denovo diagnosed diabetic patients with EPN was complete with resumption of normal renal function. In our patients, nephrectomy was done as a secondary intervention rather than as primary. All our nephrectomised patients survived possibly due to initial stabilization and better patient selection. A systematic review of 10 retrospective studies including 210 patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis regarding the timing and nature of intervention noted that mortality associated with medical management plus percutaneous catheter drainage was significantly lower than medical management plus emergency nephrectomy (13.5 vs. 25 percent, respectively).[5]

Our series is highlighted by female preponderance, greater severity of disease at initial presentation, a case of recurrent EPN, and EPN in renal allograft recipient. Though longer duration of DM, poor glycemic control, multi-organ dysfunction, and greater severity of renal involvement are well known poor prognostic factors, we did not find any single clinical or lab parameter to be associated with adverse prognosis unless associated with multi-organ dysfunction. Thrombocytopenia, acute renal failure, altered mentation, and shock are among the factors proposed by Huang and Tseng to contribute to a poor outcome.[3] The clinical triad of shock, thrombocytopenia, and altered sensorium connoted poor survival in our series too (altered sensorium: Chi-Square = 7.9648, P = 0.0048 and thrombocytopenia: Chi-Square = 6.9405; P = 0.0084).

The risk of developing EPN is increased in females with diabetes as they have a 26% incidence of asymptomatic bacteriuria (a risk factor for pyelonephritis) compared with 6% in non-diabetic females.[67] Most of our patients were middle-aged females with poorly controlled diabetes. E. coli and Klebsiella pneumonia are the most common organisms isolated from urine culture as seen in our patients as well. Non-diabetic patients with EPN have a higher incidence of urinary obstruction though we had no such patients.[248]

A meta-analysis of seven retrospective cohort studies examined 23 risk factors in 175 patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis[2] with the overall mortality rate of 25%. Four major risk factors were significantly associated with an increased risk of mortality: Class IV EPN, renal parenchymal necrosis with either no fluid content or a streaky/mottled gas pattern on imaging, conservative therapy defined as fluid resuscitation and antimicrobials without PCD, and thrombocytopenia. We had similar observation though we had very little mortality to conclude.

Our study is limited by its retrospective design and small size, which limit the strength of statistical inference drawn from it. Greater mortality in surgically treated patients was most likely due to greater severity and poor response to antibiotics. The previous Indian series of 39 cases of EPN with female preponderance had overall mortality rate of 13% similar to our series.[9]

Good glycemic control in diabetics, earlier diagnosis, and prompt management of urinary tract infections may prevent the development of emphysematous pyelonephritis. All patients with complicated urosepsis (especially diabetics) should be evaluated radiologically before being started on empirical therapy. The diagnosis is established radiologically by screening ultrasonography followed by confirmatory CT scan of patient with urosepsis who fail to improve in 48-72 h of treatment. Nephrectomy is indicated only after unsuccessful attempts to salvage the kidney even after appropriate antibiotics, PCD, or stenting of obstructed ureter.

Conclusion

The clinical scenario of EPN has changed over the years, which is reflected in our study. Earlier EPN used to be synonymous with perilous presentations with extensive disease. Owing to widespread availability of better investigative radiological tools, early detection (even small pockets of air in kidney in patients of urosepsis) has become possible. With more effective newer antibiotics and better intensive care including dialytic support services, the outcome in these patients has improved remarkably. There is a distinct trend of managing EPN more conservatively with favorable outcomes and impressive reductions in overall mortality. Managing EPN more conservatively has thus become the standard of care. Within the limitations of a small sample size in our study, we conclude that patients with high CT grade of lesions (III and IV) with altered sensorium and thrombocytopenia at presentation are more likely to die due to the disease and may require a more aggressive surgical plan.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Urinary tract infections in adults. In: Jurgen F, Johnson RJ, Feehally J, eds. Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology (4th ed). Mosby Elsevier Inc: Philadelphia; 2010. p. :638-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for mortality in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis: A meta-analysis. J Urol. 2007;178:880-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emphysematous pyelonephritis: Clinicoradiological classification, management, prognosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:797-805.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emphysematous pyelonephritis: A 15-year experience with 20 cases. Urology. 1997;49:343-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is percutaneous drainage the new gold standard in the management of emphysematous pyelonephritis. Evidence from a systematic review? J Urol. 2008;179:1844-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Asymptomatic bacteriuria may be considered a complication in women with diabetes. Diabetes Mellitus Women Asymptomatic Bacteriuria Utrecht Study Group. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:744-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictive factors for mortality and need for nephrectomy in patients with emphysematous pyelonephritis. BJU Int. 2010;105:986-9.

- [Google Scholar]