Translate this page into:

Survival analysis of patients on maintenance hemodialysis

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Despite the continuous improvement of dialysis technology and pharmacological treatment, mortality rates for dialysis patients are still high. A 2-year prospective study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital to determine the factors influencing survival among patients on maintenance hemodialysis. 96 patients with end-stage renal disease surviving more than 3 months on hemodialysis (8-12 h/week) were studied. Follow-up was censored at the time of death or at the end of 2-year study period, whichever occurred first. Of the 96 patients studied (mean age 49.74 ± 14.55 years, 75% male and 44.7% diabetics), 19 died with an estimated mortality rate of 19.8%. On an age-adjusted multivariate analysis, female gender and hypokalemia independently predicted mortality. In Cox analyses, patient survival was associated with delivered dialysis dose (single pool Kt/V, hazard ratio [HR] =0.01, P = 0.016), frequency of hemodialysis (HR = 3.81, P = 0.05) and serum albumin (HR = 0.24, P = 0.005). There was no significant difference between diabetes and non-diabetes in relation to death (Relative Risk = 1.109; 95% CI = 0.49-2.48, P = 0.803). This study revealed that mortality among hemodialysis patients remained high, mostly due to sepsis and ischemic heart disease. Patient survival was better with higher dialysis dose, increased frequency of dialysis and adequate serum albumin level. Efforts at minimizing infectious complications, preventing cardiovascular events and improving nutrition should increase survival among hemodialysis patients.

Keywords

Hemodialysis

mortality

survival

Introduction

The prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) is increasing with an enormous financial burden on society.[12] About 50 years ago, ESRD was invariably lethal. Although maintenance dialysis methods have now successfully prolonged the life of patients with terminal uremia, mortality remains high.[3]

Approximately 9-13% of patients on hemodialysis in India die within 1 year.[4] The adjusted rates of all-cause mortality are 6.3-8.2 times greater for dialysis patients than the general population.[5] The adequacy of dialysis and factors such as pre-dialysis care, late referral to specialized nephrological team and non-compliance affect patient survival.

The gold standard of dialysis therapy is yet to be identified. Newer approaches are required to improve overall mortality rates and to achieve an acceptable level of survival and rehabilitation in hemodialysis patients.[6] We investigated the outcome on hemodialysis and the factors, which had an impact on survival in our hemodialysis cohort.

Subjects and Methods

Consecutive patients with ESRD who survived the first 3 months on maintenance hemodialysis were enrolled prospectively over a period of 2 years. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee and an informed consent was obtained from all the patients. Both the patient and his/her relatives were subsequently interviewed and data entered into an electronically compatible proforma. Patients were diagnosed to have ESRD if they had an irreversible decline in renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate by Cockcroft-Gault formula)[7] for more than 3 months. The diagnosis of underlying kidney disease was based on clinical, laboratory and radiological features. Kidney biopsies were done when indicated.

Patients with acute renal failure, those who dropped out or who were switched over to other forms of renal replacement therapy like continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and renal transplantation after inclusion into the study were excluded.

At baseline, i.e. 3 months after the start of dialysis, information was collected on the demographic profile, underlying kidney disease and comorbid conditions. At baseline and every 3 months after the start of therapy, information was gathered on the nutritional status, blood pressure, investigations including hemoglobin, serum albumin, calcium, phosphorus, potassium and hemodialysis characteristics as per the standard proforma. The mean of the 3-month values of all the patients were finally categorized into different groups accordingly (for instance, as low, intermediate and high) and their impact on the outcome was assessed. Nutritional status was assessed essentially by body mass index and serum albumin level. The patients were followed-up for 2 years from the start of study or until death.

Hemodialysis details

Standard bicarbonate hemodialysis was performed for 4 h twice or thrice weekly. Individual proportioning dialysis machines were used with reverse-osmosis treated water. Volumetric ultrafiltration control was available in all the machines. Polysulfone hollow fiber dialyzers of mass transfer area co-efficient of 578 ml/min (500-600 ml/min) and ultrafiltration co-efficient 5.5 ml/h-mmHg were used. Dialyzate flow rate was 500 ml/min and blood flow rates were targeted as per the patient requirement. Dialyzer re-use was uniformly performed using automated methods.

Details regarding the type of vascular access, hepatitis B vaccination, erythropoietin use and the complications on hemodialysis including vascular access-related ones were recorded. Dialysis adequacy was determined using the single pool Kt/V (spKt/V) which was calculated using the second generation equation of Daugirdas[8] from pre- and post-hemodialysis blood urea (the product of the urea clearance and the duration of the dialysis session normalized to the volume of distribution of urea plus residual renal function). In accordance with large cross-sectional studies which showed an increased mortality with Kt/V < 1.2 as well as based on the 2006 Kidney Disease Outcome Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines on hemodialysis which considers a Kt/V above 1.2 as minimum dialysis dose for thrice weekly dialysis schedule,[89] the Kt/V cutoff of 1.2 was used in studying the effect of varied dialysis dose on survival in this study. Weekly Kt/V as recommended by the Indian Society of Nephrology guidelines on hemodialysis units was used in comparing the groups undergoing twice weekly and thrice weekly dialysis.[10] However, residual renal function measured by the average of 24-h urea and creatinine clearances was not determined.

The outcome of all patients in terms of survival and mortality was assessed at the end of the study. Causes of death and the factors which had an impact on survival were analyzed. The cause of patient death was determined by review of our medical records if the patient expired in our institution or by review of external death certificates when available.

Statistical analysis

Mean ± standard deviation (SD) and percentages were used for summarizing the data. Continuous variables were studied using the Student's t-test (two tailed, independent). Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square and 2 × 2, 2 × 4 Fisher's exact tests. The primary endpoint of the analysis was death. Patient followed-up was censored at the time of death or at the end of 2-year study period. Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazard analysis were used for calculation of survival. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent predictors of mortality. The confidence interval (CI) was 95% and a P < 0.05 was used for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 15.0, Stata 8.0, MedCalc 9.0.1 and Systat 11.0.

Results

A total of 113 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Nine were transplanted, 1 underwent continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD), 7 dropped out of the study and the remaining 96 patients were analyzed.

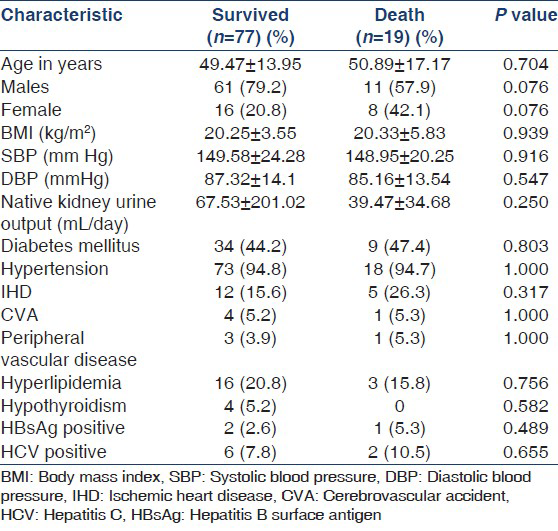

Majority of the patients were above 40 years (age 49.74 ± 14.55) and males outnumbered females in a ratio of 3:1. Diabetics comprised 44.7% of the patient population and diabetic nephropathy was the most common underlying kidney disease (44.7%). Chronic glomerulonephritis accounted for 23.95% of the cases with varied etiology namely, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (2.1%), Ig A nephropathy (3.1%) and lupus nephritis (1%) while the cause was undetermined and therefore, presumed in the remaining 17.7% of them based on clinical grounds. Similarly, chronic interstitial nephritis was presumed to be present in 6.3% patients while 2.1% had chronic pyelonephritis. 3 (3.1%) patients with failed renal transplant inducted to hemodialysis were also included in the study with the diagnosis of chronic allograft nephropathy. 15.6% cases had shrunken kidneys precluding histopathological diagnosis and were categorized as unknown group [Table 1, Figure 1].

- Native kidney disease

Nearly 80.2% of the patients were on twice weekly hemodialysis and Arteriovenous Fistula (AVF) was the permanent vascular access in most of them [Table 2].

Nineteen (19.8%) out of the 96 patients studied died. The mean time to death since start of hemodialysis was 176.84 days (5.9 months) and the estimated mean survival time was 570 days (19.2 months).

Sepsis and ischemic heart disease (IHD) were the most common causes of death both accounting for nearly 60% of the overall mortality [Figure 2]. A significant number of those deaths occurred in the first 6 months of starting dialysis therapy. The cause of death was not known in 10.5% cases. Among the infections, vascular-access related infections accounted for 23.5% and the remaining were mostly due to urinary tract infection, pneumonia and cellulitis, more so in diabetics.

- Causes of death in the cohort (n= 19)

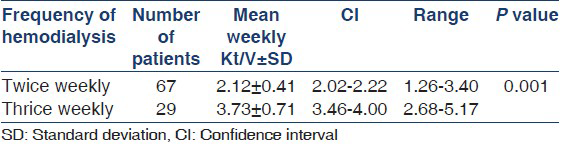

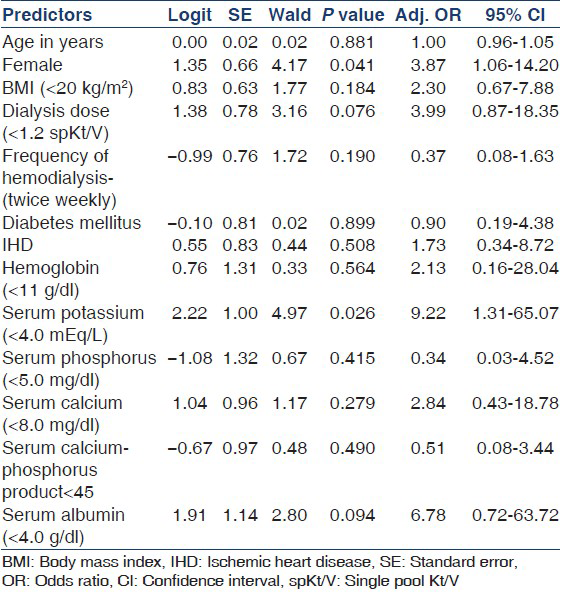

Weekly Kt/V ranged from 1.26 to 5.17 in this study and there was a significant difference between the twice weekly and thrice weekly dialysis groups [Table 3]. There was no difference in the outcome with regard to hemoglobin and calcium-phosphorus product levels [Table 4]. As can be seen in Table 5, the age-adjusted multiple logistic regression analysis showed the female gender and hypokalemia to be the strong predictors of mortality. On the other hand, lower dialysis dose (Kt/V <1.2) and lower serum albumin (<4 g/l) did not predict mortality though they were shown to be associated with poor outcome in the univariate analysis. This probably could be attributed to the interactions and effect modulations between the various independent factors considered in the multivariate analysis.

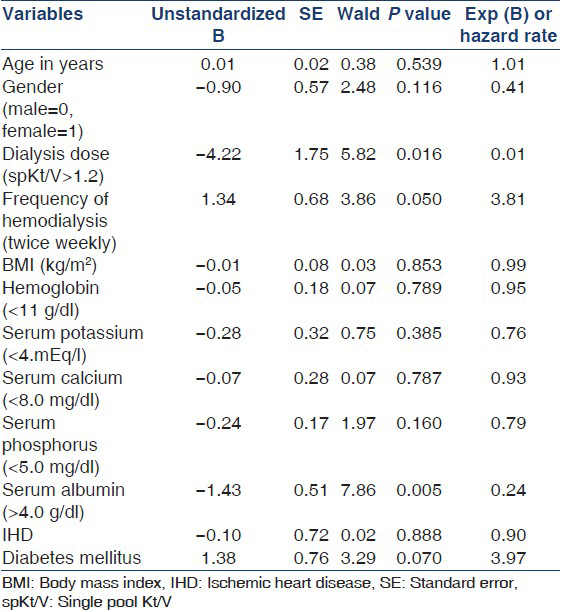

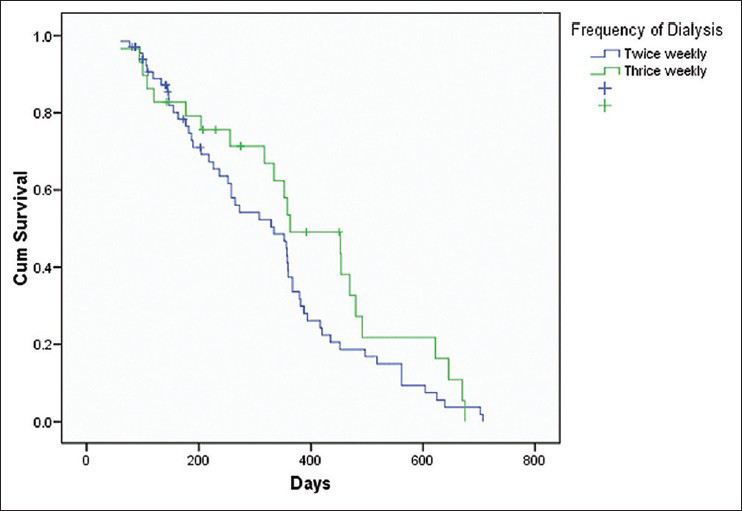

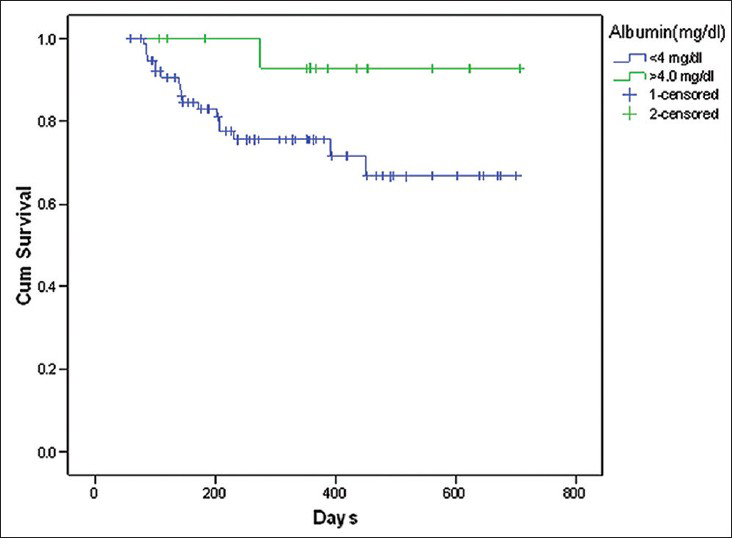

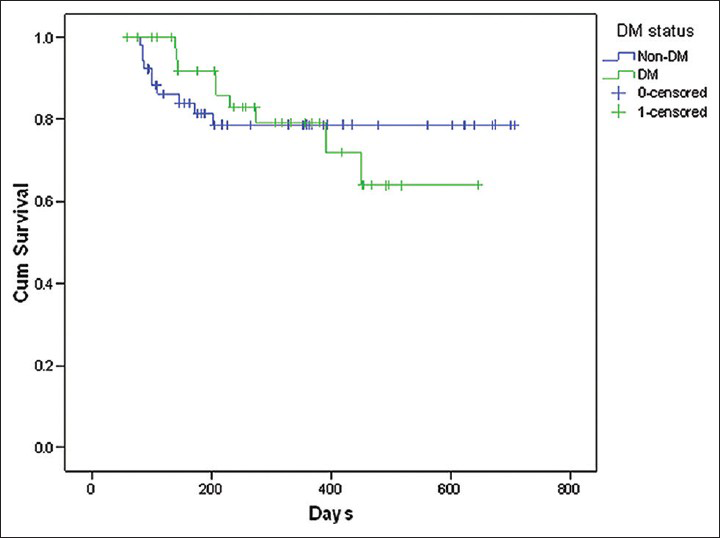

Among the variables included for assessing survival functions using Cox-regression model, dialysis dose delivered (spKt/V), frequency of hemodialysis and the level of serum albumin were found to be significantly affecting the survival [Table 6]. The patients who received a higher dose of dialysis (Kt/V >1.2) had a survival advantage over those with lesser delivered dose of dialysis (Kt/V < 1.2). This was statistically significant (Hazard Ratio [HR] 0.01, P = 0.016). Similarly, those who underwent twice weekly hemodialysis had 3.81 times lesser chances of survival when compared to those with thrice weekly dialysis (P = 0.05). Serum albumin level >4 g/dl was associated with better survival (HR 0.24, P = 0.005). Though the proportion of patients with diabetes mellitus was large, there was no significant difference between those with and without diabetes in relation to survival [Figures 3-6].

- Cumulative patient survival and dialysis dose (Kt/V)

- Cumulative patient survival and frequency of hemodialysis

- Cumulative patient survival and serum albumin level

- Cumulative patient survival and diabetes status

Discussion

Analysis of our data at the end of 2 years revealed that 19 out of 96 patients died with an estimated mortality rate of 19.8% which is considerably higher than what is reported by Mittal et al. (12.5%)[11] and Rao et al. (9.5%)[4] but compares favorably with the United States renal data system (USRDS) data (21%).[12]

The patients who expired were in general as a cohort, middle aged (50.89 ± 17.17). Though there were thrice as many males as females in this study, females had a greater risk for death with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 3.9 and were found to predict mortality independently on an age-adjusted multivariate logistic regression analysis. This, however, does not agree with the findings of Depner et al.,[13] who demonstrated a survival advantage in females with increased dialysis dose as compared to males. It is worth noting that there was no significant difference in the dialysis dose delivered between males and females in our study.

The mean time to death since start of hemodialysis was 176.84 days (5.9 months) and the estimated mean survival time, 570 days (19.2 months). The largest loss of life occurred (63.12% deaths) within the first 6 months. USRDS data[12] also portrayed a consistent pattern of higher mortality rates in the first few months of dialysis, especially in the second to fourth months of treatment.

Infection and IHD were the most common causes of death in our study together leading to 63.12% of overall deaths consistent with other studies.[412] About 36.8% of the deaths occurred due to sepsis alone, mostly as a result of vascular access-related infections like an abscess of the AVF and catheter-related bacteremia. IHD contributed to 26.3% of the deaths. The mean age of those dying due to IHD was 62.8 years and majority (60%) of them were diabetics and nearly one-third smoked tobacco. Congestive cardiac failure occurred in 40% of those cases and many had moderate left ventricular systolic dysfunction (mean ejection fraction 54%). Intractable pulmonary edema as a consequence of inadequate dialysis in poorly compliant patients accounted for 15.8% of the mortality. Though there is a decline in the cardiovascular deaths in the general population presently, a similar trend has not been observed in dialysis patients owing to the fact that most dialysis patients are diabetic and many have underlying cardiac disease at the initiation of dialysis therapy itself.[14]

Withdrawal from dialysis is being recognized as yet another important cause of mortality among dialysis patients. It accounted for only 5.3% of the deaths in our study, lesser compared to 15-25% of all yearly deaths in the United States making it the third most common cause there (after cardiovascular and infectious diseases).[12] The reasons implicated for foregoing dialysis are failure to thrive (42%), medical complications (35%) and vascular access failure (4%) as well as older age and absence of external financial support.

Causes of death also vary substantially according to whether the patient dies in the hospital or at home. Majority of deaths (52.6%) in our study occurred in the hospital and mostly were due to sepsis. On the other hand, it was difficult to ascertain the cause of death in patients who died at home. Among those who were brought dead, cause of death was not known in two cases, one had withdrawn from the dialysis and three cases were presumed to have had IHD (cardiac arrest).

It is a known fact that the optimum dose of hemodialysis is to maximize rehabilitation in ESRD patients. The National Cooperative Dialysis Study showed that treatment failure and patient morbidity were related to inadequate dialysis dose.[15] The Indian Society of Nephrology guidelines on hemodialysis units recommends a target weekly Kt/V of 4.2-4.8.[10] The recently conducted frequent hemodialysis network Trail reported that the total weekly Kt/V was significantly higher in the frequent-hemodialysis group than that in the conventional-hemodialysis group (3.60 ± 0.57 vs. 2.57 ± 0.26, P < 0.001). The improved outcomes persisted when residual renal function was excluded (3.54 = 0.56 vs. 2.49 + 0.27, P < 00.01).[16] Our study too documented a significantly higher weekly Kt/V in thrice weekly hemodialysis group than in the twice weekly hemodialysis group (3.73 ± 0.71 vs. 2.12 ± 0.41, P < 0.001). This establishes that inadequate dialysis is a contributor to increased mortality, which in turn implies that more intensive dialysis may improve overall survival, as possibly with nocturnal hemodialysis. Observational data reported from Tassin, France (Kt/V > 1.6) and Minnesota, United States (Kt/V > 1.3) where patients, even those in high risk groups, were more intensively dialyzed have further substantiated this.[1718]

However, in contradiction to the above findings, the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study has demonstrated that longer dialysis 3 times/week did not improve clinical outcomes.[19] Rather, an increased relative risk of death has been observed among patients with extremely high values for Kt/V (>1.6) or urea reduction ratio (URR between 75% and 79%). Since these values reflect increased urea clearance and/or an extremely low body volume (that may represent poor nutrition), the increased mortality has been attributed to the effects of marked malnutrition.[2021]

Malnutrition per se is yet another important determinant of adverse outcome in dialysis. Factors like anorexia associated with uremia, medications, intercurrent illness, depression, economic constraint and the catabolic stress of the hemodialytic technique itself due to increased interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor contribute to undernourishment.[22] Studies by Owen et al. and Dwyer et al.[2324] have demonstrated an increased mortality in undernourished and small dialysis patients (as noted by a low body mass index) with hypoalbuminemia. For instance, a plasma albumin concentration below 4 g/l was shown to be the single laboratory finding most closely associated with an increased probability of death. Our study too revealed a 6.7 times greater risk of death in patients with a serum albumin level <3 g/l whereas those with higher serum albumin level (>4 g/l) had a statistically significant increased survival (HR = 0.24, P = 0.005) on the Cox regression. Similarly, undernutrition (Body Mass Index <20 kg/m2) carried an increased mortality risk by an OR of 2.3. Further, there was a significant association between lower dose of dialysis (Kt/V < 1.2) and decreased serum albumin (P = 0.0069) suggesting that underdialysis could adversely affect the nutritional status of the patients as shown by another study from Vellore.[25]

Majority of our patients had a hemoglobin level lower than the KDOQI recommended target hemoglobin level of 11-12 g/dl[26] despite a large percentage (51.04%) of them being on intravenous erythropoietin and maintenance iron therapy. Lower hemoglobin level and erythropoietin use did not significantly affect the outcome. Similarly, higher calcium-phosphorus product level (>55) did not show an adverse outcome in our patients. In a study by Kovesdy et al.,[27] serum potassium <4.0 or > 5.6 mEq/l was associated with decreased survival. We noted similar findings and when adjusted for age by multivariate logistic regression analysis, lower serum potassium was found to be an independent predictor of mortality increasing the OR of death by 9.22 significantly (P = 0.026). How exactly this is done is not clear, though Kovesdy has demonstrated a correlation between pre-dialysis serum potassium and nutritional markers.

Among the other factors affecting the survival, the type of native kidney disease, other co-morbid illnesses such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and cerebrovascular disease and chronic infections such as hepatitis B and C did not influence the outcome significantly. Diabetes mellitus per se did not have a statistically significant impact on the study outcome. This is in agreement with a recent study from the United Kingdom,[28] wherein the investigators did not find that diabetes mellitus was an independent predictor of mortality.

Our study attempts to highlight the importance of adequate dialysis and nutritional status in improving the survival outcome of patients on hemodialysis. It emphasizes the need for minimizing the infectious complications, especially the vascular access-related ones, by limiting the use of catheters and ensuring strict adherence to infection control measures by the nursing staff and other clinical personnel. Most of the early mortality occurring within the first 6 months on hemodialysis was contributed by IHD, hence identification of the patients at risk at the start of dialysis itself and use of prompt cardiovascular interventions and preventive care should substantially decrease the deaths related to IHD. This also calls for the role of early referral to a nephrologist which more likely results in appropriate investigations and treatment.

Prevention of malnutrition is to be given prime importance by measures like dietary counseling, adequate intake and prompt treatment of infections and correction of anemia by use of erythropoietin. Both hypo- and hyperkalemia have been associated with increased mortality. Maintaining the serum potassium within the normal limits (3.5-5.5 mEq/l) and dialyzing against appropriate dialyzate bath may improve survival.

There were several limitations to our study and foremost is that it is an observational study without a control group. There are survivor bias and selection bias as with all longitudinal studies. Selection bias was eliminated to some extent in our case as all the patients were from only one single center. The relatively small sample size also limits the power to determine risk factors. As many of the patients were referred from other places, the quality of care prior to initiation of hemodialysis, which could have possibly affected the outcome of the study, was not looked into. Serum albumin and body mass index were used as markers of malnutrition. Use of other indicators like subjective global assessment, C-reactive protein (CRP) and serum transferrin would have been more informative. All our patients on twice weekly hemodialysis were offered 8 h/week dialysis. Recent guidelines[10] recommend determination of the residual renal function measured by the average of 24-h urea and creatinine clearances once in 6 months and to offer twice a week (8 h/week) hemodialysis to patients with residual renal function > 2 ml/min and to increase the frequency and duration of dialysis in those with < 2 ml/min. We could not adhere to the above guidelines as our 2-year study began well before the guidelines were formulated. Nevertheless, subsequent efforts to increase the duration of dialysis in those undergoing twice weekly dialysis were unsuccessful due to cost constraints.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that early mortality in patients on maintenance hemodialysis was disproportionately high. The most common causes of death were sepsis and IHD. Female gender and hypokalemia were the independent predictors of mortality. Increased delivered dose of dialysis conferred a survival advantage along with increased frequency of dialysis and serum albumin level. However, there appeared to be no significant difference in terms of survival among diabetics compared with non-diabetics. These data suggest that strategies to minimize the infectious complications, prevent cardiovascular events and improve nutrition should increase the survival outcomes among hemodialysis patients. Though it is highly implausible to address these issues in a large randomized controlled trial, such studies are always desirable.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- The incidence of end-stage renal disease is increasing faster than the prevalence of chronic renal insufficiency. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:95-101.

- [Google Scholar]

- ESRD patients in 2004: Global overview of patient numbers, treatment modalities and associated trends. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:2587-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcome in hemodialysis: Morbidity and mortality. J Nephrol. 2004;17(Suppl 8):S87-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Haemodialysis for end-stage renal disease in Southern India – A perspective from a tertiary referral care centre. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:2494-500.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic hemodialysis prescription: A urea kinetic approach. In: Daugirdas JT, Blake PG, Ing TS, eds. Handbook of Dialysis (4th ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007. p. :146-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy, update 2006. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(Suppl 1):S2-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- ISN Hemodialysis Guideline Workgroup. Indian Society of Nephrology guidelines on hemodialysis units. Indian J Nephrology. 2012;22(Suppl):28.

- [Google Scholar]

- United States Renal Data System. Excerpts from USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;1(Suppl 1):S1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dialysis dose and the effect of gender and body size on outcome in the HEMO Study. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1386-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- United States Renal Data System. Excerpts from USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55(Suppl 1):S1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of the hemodialysis prescription of patient morbidity: Report from the National Cooperative Dialysis Study. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1176-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-center hemodialysis six times per week versus three times per week. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2287-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urea index and other predictors of hemodialysis patient survival. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;23:272-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of dialysis dose and membrane flux in maintenance hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2010-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exploring the reverse J-shaped curve between urea reduction ratio and mortality. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1872-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dialysis dose and body mass index are strongly associated with survival in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1061-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protein and amino acid metabolism in uremia: Influence of metabolic acidosis. Kidney Int Suppl. 1989;27:S205-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The urea reduction ratio and serum albumin concentration as predictors of mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1001-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Are nutritional status indicators associated with mortality in the Hemodialysis (HEMO) Study? Kidney Int. 2005;68:1766-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- KDOQI. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline and Clinical Practice Recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease: 2007 update of hemoglobin target. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:471-530.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum and dialysate potassium concentrations and survival in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:999-1007.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is there a rationale for rationing chronic dialysis? A hospital based cohort study of factors affecting survival and morbidity. BMJ. 1999;318:217-23.

- [Google Scholar]