Translate this page into:

Towards achieving national self-sufficiency in organ donation in India – A call to action

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

“If you have a line of naked individuals, devoid of external signs of societal position, and you can recognize the rich from the poor simply by counting their kidneys, is that the kind of world you want to live in ?”

Dr. Luc Noel, Coordinator, Clinical Procedures, World Health Organization (New York Times, 17 August, 2014)

“The task before us is clear and that task remains a beckoning frontier… we must increase organs from the deceased and make them available for transplantation”.

“The challenge is to make transplantable organs from the deceased to those in need – not because they are certain class or culture – but because they are our fellows and common man and in need of our help”.

“The work of organ donation is hard but… measures the best of us in humanity”.

Dr. Francis L Delmonico, President, the Transplantation Society (Presidential Oration, World Transplantation Congress, San Francisco, 2014)

Every description of advances in organ transplantation starts by extolling the virtues of surgical technique and medical management of recipients. Indeed the success of modern day transplantation owes a lot to these progresses. However, underpinning all organ transplants is that act of supreme human charity – willingness to donate an organ – either of oneself, or that of a loved one (in the case of deceased donors) even in the face of tragedy.

All transplant professionals and patients with end-stage organ failure are painfully aware that availability of organs is a major limitation in current day practice of transplantation. This shortage has led to suggestions of ways of overcoming this barrier: use of organs from donors after cardiac death, marginal donors, transplantation across ABO barrier, swap and domino transplants, etc. All of these all have met with broad approval and were being practiced increasingly - albeit with varying success – in different parts of the world.

The one suggested solution that has created deep divisions among transplant professionals, ethicists, social scientists, law-makers and even the general public, is the suggestion of incentivizing organ donation.[1] Altruism, consistent with respect for fundamental human rights - in particular that of human dignity - has been the bedrock of organ donation, and the overwhelming consensus so far has been that any kind of payment or reward for organ donation is contrary to the human values, and hence banned throughout the world – with the notable exception of Iran.[2]

Professional societies, transnational organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and other global groups have strongly opposed incentives for organ donation, at the same time supporting removal of any disincentive such as loss of wages, medical bills, medical insurance, travel expenses etc., related to the act of donation.[34567] These voices include WHO Guiding Principles and the Declaration of Istanbul, which provide guidance on how to remove such disincentives. The Indian Society of Nephrology and the Indian Society of Organ Transplantation have endorsed the Declaration of Istanbul, and many countries have enacted laws in accordance with these principles.

Despite such seemingly broad consensus against payments, the appropriateness of financial incentives for organs continues to be debated in the pages of professional journals and the lay press.

While academic debate is always welcome, distressing are regular appearance of reports of continued exploitation of the impoverished vulnerable population as source of organs for the rich in clear violation of existing laws banning such commercial transactions from different parts of the world – the most recent one being an exhaustive coverage of the situation in Israel in the pages of the influential New York Times (http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2014/08/21/how-much-for-a-kidney).

Should this concern us here in India?

India came to limelight in the late 1980s as the preferred destination for rich foreigners in search of organs for a price. This was subsequently termed “transplant tourism.” The details are well documented and need not be repeated here. What is of concern that such reports continue to appear – at least in the lay press – in India even today. Police action, arrests, prosecution and even conviction of the accused have been reported.[891011] The recent amendments in the THOA[1213] have made the penal provision for violations even stricter. Despite these, the law continues to be violated.[14] Some “famous” cases even have their own Wikipedia page.[15]

Almost every transplant professional in India knows that commercial transplants continue in India – albeit the volume is nowhere close to that in the 1990s.[16] Patients suddenly disappear from dialysis units and surface after some time, with a mask covering the face, a sign of having got a kidney transplant. Details are hard to come by, but an ongoing activity is suspected. This phenomenon - that only a small portion of illegal activity is visible - has been called “the dark figure of crime” or “the iceberg of crime”.[17] Practioners of this trade (patients, middlemen, healthcare professionals, administrators) play hide and seek with law enforcement – patients travelling across state borders to seek donors, travelling with paid donors to other states and even overseas, surgeons flying out to other hospitals – innovation knows no bounds. Notably, a majority of these transplants have been done with the approval from the Authorization Committees charged with the responsibility of making sure that there is no commercial transaction.

One can argue that a section of professionals do not agree to the altruism principle behind organ donation and, therefore, do not believe payment should be prohibited. They are well within their right to hold such beliefs – and join in the often lively debate on the topic.

However, the fact is that making, receiving and facilitating payment of any sort for organ donation is illegal in India. Therefore, no matter how strongly held, such beliefs cannot be translated into practice.

Since transplants are cleared by the Authorization Committees, professionals claim to be operating within the bounds of the law. While literally correct, it is hard to believe they are completely ignorant of the goings on. On the occasion, an enterprising donor-recipient pair might manage to dupe everyone, but when such instances are alleged in large numbers - that too only in some centers - this argument fails to wash, raising suspicions about complicity of healthcare professionals and hospital administrators.[17]

The obvious solution for this is to improve our deceased donation transplant program. The Government of India set up the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization for this purpose about 3 years ago.[1819] The body has largely been inactive, however. Despite the announcement of the National Organ Transplant Policy and framework, the Deceased Donor program remains stillborn in most parts of India. The Union Minister for Health and Family welfare agreed recently that the organization has failed to make an impact.[20]

Notable exceptions have been the state of Tamil Nadu and to a lesser extent Gujarat. The Tamil Nadu Deceased Donor Donation program[21] and the Tamil Nadu Network for Organ Sharing[22] have adopted forward looking policies. There is a declared organ allocation policy, state - wide organ sharing system, and a common wait list. Organ donation data is available on the website. All this has been largely made possible by a dedicated team. The deceased organ retrieval rate in Tamil Nadu is 1.3/million population (pmp),[23] about 10 times more than the rest of the country. Data from the small Union territory of Chandigarh shows an even greater retrieval rate of 9.5 pmp.[24] These examples show that given the will, it is indeed possible to improve performance.

A perusal of Tamil Nadu data shows that whereas 100% of the 603 kidneys and the 268 livers retrieved from deceased donors went to Indian citizens, only about 75% of the 34 hearts were transplanted into Indian Nationals, with the rest going to foreigners (Amlorpavanathan, personal communication). It must be clarified here that this was with full adherence to the organ allocation policy which says that the resident of the state have the first claim over any available organ, followed by Indian citizens from other state, and only if there is no suitable recipient on the wait list would the organ go to a foreign citizen (rather than being discarded, the only available – but much less attractive - alternative).

Do any of us believe that the need of a heart transplants is so limited in our country? This data suggests a diversion to foreigners of a national resource that should benefit the Indian citizens. The admirable improvement in organ retrieval has outstripped the pace at which systems that should allow the use of these organs by the citizens need to progress. However, the factors that deny access to costly heart transplant to the ordinary Indian are beyond the scope of discussion here.

Another area we have largely neglected is providing long-term preventive healthcare to living donors. It has been long believed that living kidney donation is free from risk in healthy subjects. Emerging data, however, suggest that healthy live donors might be at increased risk of developing kidney disease in the long-term,[25] making it imperative that they be assured of continued medical care in return to their selfless act.

What should be done? Reassuringly, the existing rules and laws governing organ transplantation in India are pretty good and prescribe a solution for most of the issues raised above. What we need is transparency, use of information technology and better enforcement of existing rules.

Currently, the law requires that all transplant centers submit regular reports of all transplants; including recipients and donor details to the Regulatory Authority. We know that this is mostly done pro forma. This process should be immediately made electronic, and the donor and recipient information should include a field that will allow them to be identified (such as UID). This will permit immediate and continued verification of donor antecedents and curb people getting away with false claims of relationships. Immediate creation of live donor registries – provided for in the THOA - is imperative. Further, all centers should be obliged to provide preventive care to the donors. Kidney donors have difficulty finding health insurance even in developed countries.[26] Such care should, therefore, be covered under one of the existing Government insurance schemes, such as the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojna.

The existing rule of the requirement of a full time transplant co-ordinator (not assigning it to someone on a part time basis), institution of required request for organ donation and brain death audit in Intensive Care Units – all part of the THOA, should be implemented immediately and it should be the duty of all hospitals to display this information on their websites.

All hospitals that have an active living donor transplant program should be required to adhere to certain performance measures regarding deceased donation.

In their anxiety to appearing to comply with THOA, some states have gone overboard. They require even legitimate donor – recipient pairs (first-degree relatives) to be cleared by the Authorization Committee. This unnecessary step harasses patients, giving them the run around, delays transplant, increasing the expenditure and sometimes leading to recipient deaths (Shah BV, personal communication). Moreover, it increases the work of the Authorization Committees that should be concentrating on the cases that need proper scrutiny rather than wasting time on those where the legal requirements can be satisfied by other methods prescribed in rules (e.g. genetic testing). Clearly, this anomaly needs to be corrected.

Professional Societies and non-government organizations active in the field have an important role in driving the policy agenda that helps development of ethical and equitable transplant program in the country. The Indian Society of Nephrology, the Indian Society of Organ Transplantation, and the MOHAN Foundation (the leading NGO in promoting deceased donation and training Transplant Co-ordinators in India) - along with the Transplantation Society and representation of the WHO, conducted a workshop in February 2013 that led to generation of a consensus document, which provides a roadmap for implanting a deceased organ donation framework [

Supplementary File 1

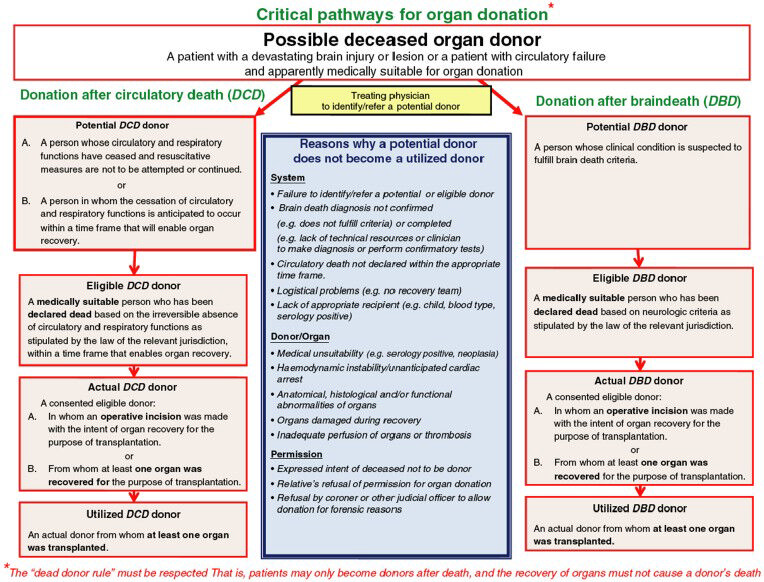

Supplementary File 1 Consensus Recommendations from ‘National Workshop of Transplant Coordinators’ India Habitat Centre, Feb 28-March 2, 2013Alongside education of general public, there is a clear need of educating healthcare professionals, including intensivists, neurosurgeons, neurologists, and hospital administrators. Full understanding of the critical pathway to deceased donation[27] [Figure 1] is critical to this education and suggests how regular ascertainment of donor status can be done, tracked over time and compared. Involvement of other professional Societies, such as those consisting of the above-mentioned fields is critical for progress.

- Critical pathways for organ donation (reproduced from Domínguez-Gil, et al. Transpl Int 2011 Apr;24:373-8)

We need more research on the existing barriers to deceased donation and how can they be overcome. Studies that have examined the attitude of general public and healthcare workers have found overwhelming support for organ donation.[28] Still, the rates of organ utilization from deceased donors remains woefully low in India. Even in Tamil Nadu, the organ procurement rate is well below that in most countries with established programs. In a study from PGIMER, over a 6 month period using an internationally validated pathway for organ donation, only 8% of the eligible brain dead donors could be converted into actual donors.[24] We need to collect more data, including qualitative research to examine the barriers and facilitators to deceased donor transplants including exploring issue like how to engage the intensivists better, and expanding deceased donor pool such as donation after cardiac death.

The Indian medical community - including those engaged in the field of organ transplantation - is highly skilled and globally respected. It is time we engage to a greater degree with all stakeholders in improving the organ donation processes, so that the majority of Indians in need of organs have access to them in a way that respects human values and dignity.

References

- The case against a regulated system of living kidney sales. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:466-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The history of organ donation and transplantation in Iran. Exp Clin Transplant (12 Suppl 1):38-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO Guiding Principles on Human Cell, Tissue and Organ Transplantation. Available from: http://www.who.int/transplantation/Guiding_PrinciplesTransplantation_WHA63.22en.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Organ trafficking and transplant tourism and commercialism: The Declaration of Istanbul. Lancet. 2008;372:5-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2010/53/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on standards of quality and safety of human organs intended for transplantation. European Commission. Available from: http://www.eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri.=OJ:L:2010:207:0014:0029:EN:PDF

- [Google Scholar]

- Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine concerning Transplantation of Organs and Tissues of Human Origin. Available from: http://www.conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/186.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. Available from: http://www.conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/Treaties/Html/164.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Gurgaon Kidney Racket Kingpin Dr Amit Convicted. Available from: http://www.zeenews.india.com/news/haryana/gurgaon-kidney-racket-kingpin-dr-amit-convicted_837210.html

- [Google Scholar]

- City Cops to Visit Kolkata on Kidney Racket Trail. Available from: http://www.newindianexpress.com/states/odisha/City-Cops-to-Visit-Kolkata-on-Kidney-Racket-Trail/2014/07/14/article2329847.ece

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney racket probe in Kolkata unlikely to net the kingpins. TOI. Available from: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/kolkata/Kidney-racket-probe-in-Kolkata-unlikely-to-net-the-kingpins/articleshow/38607364.cms

- [Google Scholar]

- Court holds six, including 5 docs, guilty in kidney scam. Hindustan Times. 2013. Available from: http://www.hindustantimes.com/punjab/amritsar/court-holds-six-including-5-docs-guilty-in-kidney-scam/article1.1146772.aspx

- [Google Scholar]

- Organs transplant Act notified. 2014. The Hindu. Available from: http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/organs-transplant-act-notified/article5588655-ece

- [Google Scholar]

- Transplantation of Human Organs (Amendment). Act. 2011. Available from: http://www.isot.co.in/correction/transplnt2011.pdf

- [Google Scholar]

- Available from: http://www.indianexpress.com/tag/kidney-racket

- Gurgaon kidney scandal. Available from: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gurgaon_kidney_scandal

- [Google Scholar]

- Paid transplants in India: The grim reality. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:541-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Invisible Issue of Organ Laundering Transplantation. 2014 Aug 20 [Epub ahead of print]

- [Google Scholar]

- Soon, National Body to Procure, Distribute Organs. 2012. TOI. Available from: http://www.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Soon-national-body-to-procure-distribute-organs/articleshow/11583887.cms

- [Google Scholar]

- National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization. Available from: http://www.notto.nic.in/about-us.htm

- [Google Scholar]

- Organ donation: Centre must change archaic policies. 2014. Niti Central. Available from: http://www.niticentral.com/2014/08/13/organ-donation-centre-mustchange-archaic-policies-235896.html

- [Google Scholar]

- Cadaver Transplant Programme, Government of Tamil Nadu. Available from: http://www.dmrhs.org

- [Google Scholar]

- How deceased donor transplantation is impacting a decline in commercial transplantation-the Tamil Nadu experience. Transplantation. 2012;93:757-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential of organ donation from deceased donors: Study from a public sector hospital in India. Transpl Int 2014 May 23 [Epub ahead of print]

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311:579-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences obtaining insurance after live kidney donation. Am J Transplant 2014 Jul 16 [Epub ahead of print]

- [Google Scholar]

- The critical pathway for deceased donation: Reportable uniformity in the approach to deceased donation. Transpl Int. 2011;24:373-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitude and knowledge of healthcare workers in critical areas towards deceased organ donation in a public sector hospital in India. Natl Med J India. 2013;26:322-6.

- [Google Scholar]