Translate this page into:

Pregnancy in patients with chronic kidney disease: Maternal and fetal outcomes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Chronic kidney diseases (CKD) adversely affects fetal and maternal outcomes during pregnancy. We retrospectively reviewed the renal, maternal and fetal outcomes of 51 pregnancies in women with CKD between July 2009 and January 2012. Of the 51 subjects (mean age 27.8 ± 7.04), 32 had 19 had estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 ml/min. There was significantly greater decline in eGFR at 6 weeks (55.8 ± 32.7 ml/min) after delivery as compared to values at conception (71.7 ± 27.6 [P < 0.001]). The average decline of GFR after 6 weeks of delivery was faster in patients with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 at −18.8 ml/min (stage 3, n = 13, −20.2 ml/min; stage 4, n = 6, −15.8 ml/min) as compared to −15.1 ml/min in patients with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. Three of the six patients (50%) in stage 4 CKD were started on dialysis as compared to none in earlier stages of CKD (P = 0.002). At the end of 1 year, all patients in stage 4 were dialysis dependent, while only 2/13 in stage 3 were dialysis dependent (Odds ratio 59.8, 95% confidence interval 2.8–302, P = 0.001). Preeclampsia (PE) was seen in 17.6%. Only 2/32 (6.25%) patients with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 developed PE while 7/19 (36.84%) patients with GFR < 60 ml/min developed PE. Of the 51 pregnancies, 15 ended in stillbirth and 36 delivered live births. Eleven (21.56%) live-born infants were delivered preterm and 7 (13.72%) weighed < 2,500 g. The full-term normal delivery was significantly high (50%) in patients with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (P = 0.006) and stillbirth was significantly high - 9/19 (47.36%) patients with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. To conclude, women with CKD stage 3 and 4 are at greater risk of decline in GFR, PE and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes as compared to women with earlier stages of CKD.

Keywords

Chronic kidney disease

fetal outcome

pregnancy

renal outcome

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a growing healthcare problem. About 3% of women in childbearing age are affected by CKD.[12] The central role of pregnancy in the development of acute kidney damage and hypertension (HT) such as preeclampsia (PE)/eclampsia has been known for over a century whereas the relationship between PE and the subsequent CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) risk has been recently elucidated.[3]

CKD leads to poor maternal and fetal outcomes. Small studies on outcomes of pregnancies in women with moderate to severe decline in kidney function (estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2) demonstrated a substantially increased risk for adverse impact on pregnancy outcomes.[45] PE, HT, cesarean delivery and further deterioration of the kidney function are common maternal complications. The offspring that is born to the CKD mother is frequently preterm or small for gestational age. Overall fetal loss rates are also increased compared to that of the general population, and stillbirths have been observed in 4–8%[67] of pregnancies. Small case series during the 1960s showed that fetal mortality in presence of maternal kidney disease was nearly 100%,[89] and the first case of successful pregnancy outcome in a patient on dialysis was considered a “miracle of medicine”[10] Diseased kidneys may be unable to adapt to the normal physiologic changes of pregnancy leading to perinatal complications.[1112] Robust literature evidence in this regard is still lacking from this part of the world where maternal and fetal mortality is very high as compared to the developed world.[131415] We analyzed the risk of adverse renal, maternal and fetal outcomes in women with CKD.

Patients and Methods

This was a retrospective observational study of patients with CKD and pregnancy seen between July 2009 and January 2012. CKD was defined as per standard definition of CKD by kidney disease outcomes quality initiative guideline.[16] Patients with diabetes, other systemic diseases, acute renal failure and patients with history of multiple fetal losses before developing CKD were excluded. Pregnancy in nephrotic syndrome (NS) patients in partial remission was included in the study. NS patients in complete remission were not considered having CKD.

HT was considered present if there were 2 blood pressure measurements >140/90 mm Hg or there was history of antihypertensive drug use. For women without baseline HT and proteinuria, PE was defined as the abrupt onset of HT after 20 weeks of gestation associated with the appearance of proteinuria with protein excretion > 300 mg/day. For patients with baseline HT and proteinuria, doubling of protein excretion associated with exacerbation of HT after 20 weeks supported the diagnosis of PE. For patients with HT and who could not have proteinuria measured because of oligoanuria, the presence of systemic manifestations of the disorder, such as thrombocytopenia, increased hepatic transaminase levels, persistent headache, blurred vision, or epigastric pain, were used to support the diagnosis of PE.[17181920]

During pregnancy, all patients had at least one visit per trimester with clinical and laboratory assessment. Baseline and updated values for hypertensive status, proteinuria and treatments were recorded. Worsening of HT during pregnancy is defined as an increase of 20 mm Hg in diastolic blood pressure from pre-pregnancy values or need for antihypertensive drugs in previously normotensive subjects. Proteinuria was assessed by means of 24-hour urine collection after careful patient instruction and was checked at least twice.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated using the CKD epidemiology collaboration equation and expressed in ml/min/1.73 m2 of body surface area.[21] Rate of progression was assessed before and after pregnancy as loss of GFR in ml/min. Reference points used for the assessment of progression rate were the first GFR at conception, at 6 weeks after delivery, and at the end of follow-up. Serum creatinine measurements, used to establish reference points for the rate of GFR loss, were checked at least twice, and in the case of discrepancies, the mean value was adopted.

Fetal outcome was analyzed in terms of pre-term and full-term delivery, stillbirth and low birth weight. Stillbirth was defined as the occurrence of intrauterine fetal death after 24 weeks of gestation. Preterm delivery was defined as a live birth before the 37th week of gestation. Pregnancy was considered successful if it resulted in a live infant who was discharged from the hospital. Low birth weight is defined as a live-born infant weighing <2,500 g.

Outcome criteria

The primary maternal outcome was decline in renal function after pregnancy at 6 weeks after delivery at completion of puerperium when the physiological changes related to pregnancy is settled. The other outcome criteria were doubling of the serum creatinine and 50% decline in GFR or ESRD at 1 year of follow-up. The fetal outcome was analyzed in terms of full-term and preterm delivery, stillbirth, and low birth weight.

Statistical analysis

All the data were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 16 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Student's t-test was used to compare the mean values between two groups. One-way Analysis of Variance and Bonferroni test was used to compare the differences in mean values of >3 variables. The Chi-square test was used to compare the categorical variables between the groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Fifty-one women satisfying eligibility criteria were included in the study. The demographic profile and clinical characteristics of all patients at baseline of the study, in patients with different stages of CKD are shown in Table 1. The mean systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure, was significantly higher in women with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 compared to that of GFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. The 24-hour urinary excretion at baseline was higher in women with GFR > 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 as compared to women with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 [Table 1]. The proportion of patients who developed PE was significantly higher in women with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 as compared to that of GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. None of the patients with GFR of < 15 ml/min/1.73 m2 at conception continued their pregnancy in our study. Only one women (GFR 11.8 ml/min) with GFR of < 15 ml/min/1.73 m2 had reported with 8 weeks pregnancy during the study period. She had opted for medical termination of pregnancy and was excluded from analysis.

Renal outcomes

Table 2 shows the changes in GFR values in different stages of CKD women with pregnancy at 6 weeks and 1-year follow-up. There was a significantly greater decline in mean GFRs at 6 weeks (55.8 ± 32.7 ml/min) after delivery as compared to values at conception (71.7 ± 27.6 (P < 0.001) in a whole cohort of patients. The decline in GFR at 6 weeks after delivery was observed in all group of patients; however, the average decline was faster in patients with GFR < 60 ml/min−1 −18.8 ml/min (stage 3 n = 13, −20.2 ml/min; stage 4 n = 6, −15.8 ml/min) as compared to − 15.1 in patients with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min. Three of the six patients (50%) in stage 4 CKD reached ESRD and were started on dialysis as compared to none of in earlier stages (stages 1–3) of CKD after 6 weeks of delivery (P = 0.002).

At 1 year follow-up all patients (100%) in stage 4 were dialysis-dependent, while only 2/13 in stage 3 were dialysis-dependent (odds ratio (OR) 59.8, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.8–302, P = 0.001). However, four other patients in CKD stage 3 also had decline in GFR by more than 50%. None of the patients in CKD stage 1 or 2 required dialysis, only four of the 32 had decline in GFR by 50% from the baseline values. The OR of deterioration in GFR was greater in CKD stage 3 (OR: 5.49, 95% CI: 1.04–36.1, P = 0.001) as compared to stages 1/2.

The mean proteinuria was higher in patients with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min group at 1264 mg/day as compared to 633 mg/day in patients with < 60 ml/min group.

All eight patients with NS were at least in partial remission at the time of pregnancy and had GFR ≥ 60 ml/min. Of them, three had minimal change disease (MCD) and five had focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). Only one out of three MCD patients had noticed increased proteinuria to nephrotic range post-delivery while three out of five FSGS patients had nephrotic proteinuria post-delivery and one of them also had increased serum creatinine from 0.98 mg% to 2.3 mg%. These three MCD patients had proteinuria of 480 ± 310 mg/day at conception, which increased to 3.4 ± 0.91 g/day post-delivery after relapse and the five patients of FSGS who had 620 ± 450 mg/day proteinuria at conception, which increased to 4.38 ± 1.24 g/day post-delivery.

Maternal and fetal outcomes

The overall incidence of PE was 17.6%. However, only 2/32 (6.25%) patients developed PE in patients with GFR ≥ to 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 group while 7/19 (36.84%) developed PE in groups of patients with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. The risk of developing PE in patients with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 was 7.3 (95% CI: 1.34–93.4) times greater than the patients with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 group (P = 0.005).

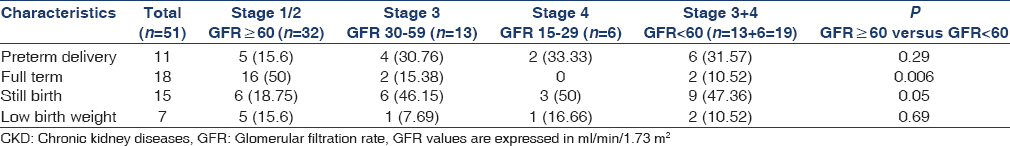

Table 3 shows the fetal outcome of the patients in different GFR categories. Of 51 pregnancies, 15 ended in stillbirth and 36 delivered live births. Eleven (21.56%) of the live-born infants delivered preterm and 7 (13.72%) infants weighed < 2,500 g. The full-term normal delivery was significantly higher (50%) in patients with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 as compared to the patients with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (10.6%) (P = 0.006). The incidence of stillbirth was significantly higher 9/19 (47.36%) in group of patients with GFR < 60 ml/min as compared to 6/32 (18.75%) with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min group of patients. The preterm delivery was numerically greater, though statistically insignificant 6/19 (31.6%) in patients with GFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 as compared to 5 (15.6%) in patients with GFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2. The incidence of low birth weight was similar in both groups of patients.

None of the patients died due to pregnancy-related complications in both groups of patients with GFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 and GFR of <60 ml/min/1.73 m2. However, two patients died, one in CKD stage 3 who reached ESRD after 6 months but did not agree for dialysis, and another in stage 4 CKD who died after 8 months of delivery because of urinary tract infection, sepsis and multi-organ failure. Out of the eight patients who reached ESRD, two died, four were continued on dialysis and two underwent renal transplantation.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that the maternal and fetal outcomes were adversely associated with CKD. The women with GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, CKD stages 4 and 3 were at greater risk of decline in GFR and developing ESRD, PE, stillbirth, and prematurity as compared to CKD women with ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2. The number of pregnancies in different CKD stages with highest number in stage 1 or 2 (n = 32), stage 3 (n = 13), stage 4 (n = 6) and only one stage 5 reflected the expected distribution of pregnancy in CKD population as the fertility also declines with decline in GFR values and moreover women did not want to continue pregnancy with advancing CKD because of poor maternal and fetal outcome.

The important observation in our study was that post-delivery decline in GFR and development of ESRD in CKD patients with pregnancy was faster in patients with stage 3 or 4 CKD at the time of conception as compared to stage 1 or 2 CKD (GFR >60 ml/min/1.73 m2) at conception. In normal pregnancy, there is always a gestational physiological increase in GFR, which is attenuated in moderate renal impairment and is absent if serum creatinine is more than 2.3 mg/dl.[12] To avoid the confounding effect of changes in GFR because of physiological changes during pregnancy, we have estimated GFR at 6 week of delivery when all physiological changes related to pregnancy is normalized and then at the end of 1 year of follow-up. Although, decline in GFR was observed in all groups of CKD patients, faster decline happened in later stages of CKD.

The post-delivery risk of decline in GFR and developing ESRD was highest in CKD stage 4 followed by stage 3 and stage 1 or 2, respectively. The role of degree of renal impairment at baseline as a major predictor of pregnancy related progression of renal disease was emphasized in a previous study.[6] Severe decline in kidney function in approximately 25% to 50% of cases was also reported from other studies. The comparison of the present study outcome with the literature evidences is difficult because of the different categorizations of the results.[8222324] In one of the largest series on pregnancy in severe CKD and using GFR-based definitions, Imbasciati[15] reported an increased risk for progression to dialysis in patients with GFR <40 ml/min/1.73 m2 and proteinuria over 1 g/day. However, in this large multicenter series the time span of enrolment was wider from 1977 to 2004. At 6 weeks post delivery, none of the patients in stage 3 developed ESRD and 50% in stage 4 reached ESRD and at 1 years post delivery all CKD stage 4 declared ESRD and only two patients from stage 3 declared ESRD. The study results reflect that the pregnancy related risk of decline in GFR has not changed even in present day scenario despite the improvements in the global care and management of the CKD patients as well as the improvement in ante natal care and policies toward in hospital delivery. However, the maternal death related to pregnancy complication was negligible because of the vigilant approach of the nephrologists and obstetricians towards complications arising from pregnancy in CKD patients.

The effect of pregnancy on fetal outcomes depends on the level of renal impairment, presence of HT, proteinuria and urinary tract infection often coexist in women with CKD.[1] Over the past four decades, several studies have described the association between CKD and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes in an internal comparator group of women without CKD. Women with CKD appear to have at least twofold higher risk of developing adverse maternal outcomes compared with women without CKD even in stage 1 with normal GFR. We have observed that women with GFR < 60 ml/min are at seven times greater risk of developing PE as compared to GFR >60 ml/min/1.73 m2. We have also observed poor fetal outcomes with declining GFR in our cohort of patients. Full-term delivery was lesser and stillbirth was higher in women with CKD stages 3 and 4. In a study, Immaculate et al. have shown that premature births occurred at least twice as often in women with CKD compared with women without CKD.[20] Although there is consensus that women with CKD have a higher risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes compared with women without CKD, the magnitude of this risk is not clear, particularly in India. There is also no clear evidence with regards to the degree of risk at various stages of CKD, information needed for informed consent in women considering the risks of pregnancy. There is a need to characterize the risks associated with renal dysfunction separately from other comorbid conditions that can occur with CKD, which may also modify the outcomes of pregnancy.

The major limitations of the study are that it is a retrospective review of the data from a single center and number of patients in the study is small. However, the study population represented the patients from the state with highest maternal and fetal mortality.

Conclusions

The women with GFR of <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (stages 3 and 4) are at a greater risk of decline in GFR, PE and adverse maternal and fetal outcomes as compared to women with GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 in CKD patients. The present data will encourage additional research and prospective studies related to this subject in future.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Historical perspective of pregnancy in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2007;14:116-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preeclampsia and the risk of end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:800-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy outcome in women with primary renal disease. Isr Med Assoc J. 2000;2:178-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of pregnancy in women with moderate or severe renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:226-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney disease is an independent risk factor for adverse fetal and maternal outcomes in pregnancy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:415-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy in chronic renal insufficiency and end-stage renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:235-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Full-term pregnancy and successful delivery in a patient on chronic hemodialysis. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc. 1971;8:74-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- The kidney and hypertension in pregnancy: Twenty exciting years. Semin Nephrol. 2001;21:173-89.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of chronic pyelonephritis on pregnancy. Acta Univ Palacki Olomuc Fac Med. 1996;40:303-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy outcomes in a prospective matched control study of pregnancy and renal disease. Clin Nephrol. 1996;45:77-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy in CKD stages 3 to 5: Fetal and maternal outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:753-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and management of atypical preeclampsia-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:481e1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Report of the national high blood pressure education program working group on high blood pressure in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:S1-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- The value of uterine artery Doppler in the prediction of uteroplacental complications in multiparous women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;23:50-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of patients at risk for early onset and/or severe preeclampsia with the use of uterine artery Doppler velocimetry and placental growth factor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:326e1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy with chronic kidney disease: Outcome in Indian women. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2003;12:1019-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preterm deliveries in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2127-32.

- [Google Scholar]