Translate this page into:

Cardiac and vascular changes with kidney transplantation

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Cardiovascular event rates are high in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), increasing with deteriorating kidney function, highest in CKD patients on dialysis, and improve with kidney transplantation (KTx). The cardiovascular events in CKD patients such as myocardial infarction and heart failure are related to abnormalities of vascular and cardiac structure and function. Many studies have investigated the structural and functional abnormalities of the heart and blood vessels in CKD, and the changes that occur with KTx, but the evidence is often sparse and occasionally contradictory. We have reviewed the available evidence and identified areas where more research is required to improve the understanding and mechanisms of these changes. There is enough evidence demonstrating improvement of left ventricular hypertrophy, except in children, and sufficient evidence of improvement of left ventricular function, with KTx. There is reasonable evidence of improvement in vascular function and stiffness. However, the evidence for improvement of vascular structure and atherosclerosis is insufficient. Further studies are necessary to establish the changes in vascular structure, and to understand the mechanisms of vascular and cardiac changes, following KTx.

Keywords

Ejection fraction

endothelial function

kidney transplantation

left ventricular hypertrophy

pulse wave velocity

Introduction

Cardiovascular changes related to chronic kidney disease (CKD) are common and a major cause of morbidity and mortality.[1] Large population-based studies have demonstrated a high incidence of cardiovascular events in the CKD patients, increasing with deteriorating renal function, with the highest rates in patients on dialysis.[2345]

Kidney transplantation (KTx) is associated with improvements in mortality due to cardiovascular events, namely myocardial infarction.[67] However, the risk is still high compared to the general population.[8]

The pathological changes in cardiac and vascular, structure and function in CKD are relatively well known, however, there is evidence that improvements occur following KTx and thus, may explain the reduced cardiovascular event rates in the transplanted population.[18]

The aim of this review is to summarize the changes in cardiac and vascular, structure, and function, with KTx, from the available evidence.

Methods

A literature search was conducted on PubMed using a generic search as well as a MESH term search involving the following prospective study, renal transplantation, CKD, echocardiography, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), left ventricular function, cardiac systolic function, cardiac diastolic function, pulse wave analysis, carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT), vascular endothelium, flow-mediated dilatation (FMD), endothelial function, endothelial dysfunction, endothelium, endothelial dependent dilatation, augmentation index (AIx), atherosclerosis, and arteriosclerosis.

The search results were then analyzed in order to select the prospective studies that explored any cardiac and vascular, structure and function, changes before and after renal transplantation.

Cardiac changes with kidney transplantation

Structure

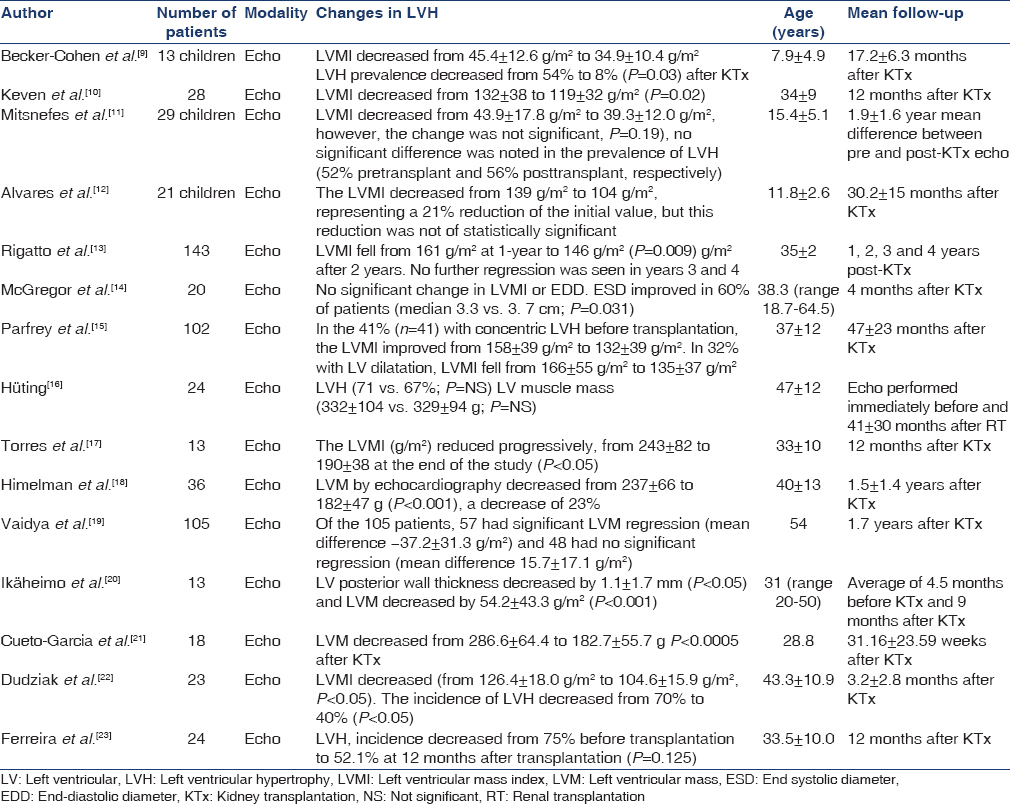

There is ample evidence that the cardiac hypertrophy associated with CKD improves with KTx. Various echocardiographic studies have demonstrated such improvements in LVH with KTx. Table 1 lists the prospective studies of LVH in CKD patients undergoing KTx.

The total numbers of patients included in the review of cardiac structural changes were 612 of which there were 63 children and 549 adults. The average ages spanned 8 ± 5 years in children to 47 ± 12 years in adults. The largest study was conducted by Rigatto et al. consisting of a prospective analysis of 143 patients and the smallest sample size was of 13 patients in three studies.[9131720]

In 11 out of the 15 studies, a significant reduction of mean LV mass index (LVMI) was noted after transplantation. The remaining four studies showed changes in LVH prevalence and LVMI but the differences were not significant.[121416] The greatest improvement in LVMI was noted by Himelman et al., with an average decrease of 55 g/m2 in 36 patients (P < 0.001).[18]

The change in LVMI was noted through a range of follow-up intervals after transplantation: As early as 3.2 ± 2.8 months and as late as 4 years postoperatively. Interestingly, in one long-term follow-up study, significant LVMI regression was observed only in the first 2 years after KTx and noted to plateau and stop beyond this time frame.[13] However, whether this trend is reflective of the general transplanted population and reproducible, remains to be seen. A major drawback of this study was that at 4 years posttransplantation, only 18 out of the 143 initial patients were available for follow-up echocardiograms.[13] Further long-term follow-up studies are, therefore, required in order to establish the potential course of LVH, years after transplantation.

The reduction in LVMI was predominantly significant for adults’ post-KTx. Although an average reduction in LVMI did occur in the studies focusing on children, in 2 out of the 3 studies, this change was not significant.[91112] This questions whether differences exist in the way hearts in children respond physiologically to the effects of a kidney transplant compared to adults.

It is unclear from the studies whether varying ages of adults influences the degree of change in LVMI. The study by Vaidya et al., explored 105 patients with a mean age of 54 years and showed a regression of 37.2 ± 31.3 g/m2 (P < 0.05) in 57 patients after transplantation.[19] In contrast, patients in the study by Ikäheimo et al. had a mean age of 31 years and showed a reduction of 54.2 ± 43.3 g/m2 in 13 patients (P < 0.001).[20] This could possibly indicate that with the exclusion of children and adolescent ages, the younger a CKD patient has a kidney transplant, the more the potential regression of the LVMI and LVH. These observations suggest more research is necessary to compare the LVMI change in younger versus older adults. The encouraging point, however, is that some degree of LVMI regression did occur irrespective of adult age.

Contrary to the above, rather than age, the length of follow-up time after transplantation may determine the degree of LVMI regression. McGregor et al. analyzed follow-up scans at an average of 4 months after KTx and found no significant difference between pretransplant and posttransplant LVMI.[16] However, Parfrey et al. analyzed patients with an average of 47 ± 23 months after transplantation and found that the LVMI improved from 166 ± 55 g/m2 to 135 ± 37 g/m2.[17] Another research avenue that could be explored is whether the more LVH one has at baseline is associated with greater regression post-KTx.

Function

There is reasonable evidence that shows improvement of cardiac function with KTx. Table 2 displays the prospective studies in adults and children demonstrating this change.

Similar to LVMI, most studies demonstrate significant improvement in both systolic and diastolic function in CKD patients following KTx.

There were 11 studies to our knowledge that described such changes following KTx. These comprised a total of 423 patients, including 29 children and 394 adults. The largest study was conducted by Parfrey et al. in whom 102 patients had their cardiac function assessed before and after KTx.[15] In comparison, the smallest study was undertaken by Sahagún-Sánchez et al. with 13 patients.[27]

A significant increase in LV ejection fraction (LVEF) posttransplantation was noted in 7 of the 11 studies. In addition, one study also demonstrated improvement in stroke volume.[16] There were four studies that showed a significant improvement in the fractional shortening after KTx.[11141527] Similarly, diastolic function had also been shown to improve following transplantation in four studies.[24262729]

The largest increase in systolic function was noted by Casas-Aparicio et al. who found that LVEF of the entire group of 35 patients had increased from 52% to 64% (P < 0.001) by 12 months after KTx.[26] In contrast, a study by Chammas et al., reported no significant change in LVEF in 32 patients at 28 ± 8 months post-KTx: The preoperative EF being 64% ± 5% and postoperative EF at 65% ± 4%.[28] Interestingly, however, in this same study by Chammas et al., there was also differing data on the diastolic function when compared with other studies. The group observed that a total of 6 patients out of 32 (19%) had diastolic dysfunction pretransplant, which decreased to five patients posttransplant. However, at 28 ± 8 months follow-up, diastolic dysfunction had increased to 7 out of 32 patients (22%).[28] Though the study suggests an improvement in diastolic function in the short-term with some deterioration long-term, overall data suggest an improvement in cardiac function. Of the two studies with the longest follow-ups, Hüting and Parfrey et al., showed significant improvements in LVEF of 5% and fractional shortening of 12%, respectively, 41–47 months after KTx.[1516]

Unlike the observation with cardiac structural changes, no difference was noted in cardiac function between studies conducted on children compared to those done on adults when assessing cardiac function, thus, indicating a general improvement across all ages.

In addition to this, no major variation or influence was seen objectively from the time of follow-up on systolic and diastolic function. Sharma et al. 2014 found that LVEF improved in 60 patients from 55% ± 9% to 64% ± 9% (P < 0.001) just 3 months after KTx.[25] In comparison, Hüting, who followed up patients at a mean time of 41 ± 30 months after renal transplantation, found that the LVEF increased from 58% ± 10% to 63% ± 12% (P < 0.02).[16] In fact, the degree of pre- to post-KTx improvement in LVEF was actually slightly smaller in patients who had echocardiograms after a longer follow-up period. Although this could be attributed to a number of factors such as hypertension and cardiac fibrosis due to immunosuppressive medications it needs further exploration with more careful research.

Vascular changes in structure and function with kidney transplantation

Structure

There have been a very limited number of prospective studies exploring changes in vascular structure in patients with CKD undergoing KTx. These are listed in Table 3.

The CIMT, which is a reliable marker of atherosclerosis, was prospectively examined in two studies only. The total numbers of patients were 78 adults and follow-up intervals ranged from 3 months to 12 months posttransplant. Only one study showed a significant reduction in CIMT after KTx.

Caglar assessed CIMT in 42 patients before and 3 months after KTx. CIMT decreased from 8.52 ± 0.96 mm pretransplant to 5.96 ± 0.63 mm posttransplant (P < 0.001).[37] In contrast, Zoungas et al. assessed CIMT in 36 patients before and 12 months after KTx.[32] No significant difference in CIMT was noted between before, 0.76 ± 0.11 mm, and after, 0.75 ± 0.14 mm, transplantation. Lima et al. assessed CIMT in 22 patients, 12–20 weeks following KTx and found that CIMT fell from 0.79 ± 0.02 mm to 0.68 ± 0.03 mm (P < 0.01).[38] Although the study by Lima shows a significant reduction in CIMT, the baseline measurement was taken 2–3 weeks after KTx in contrast to the other two studies in which the measurement was taken before the transplant.

Hence, the convincing evidence is, therefore, lacking for vascular structural changes following KTx. There have, however, been various observational studies showing lower CIMT measurements in the kidney transplant population when compared to the CKD dialysis population.[394041] Thus, more carefully planned prospective studies are necessary to explore the changes in vascular atherosclerosis with KTx.

Function

Arterial stiffness

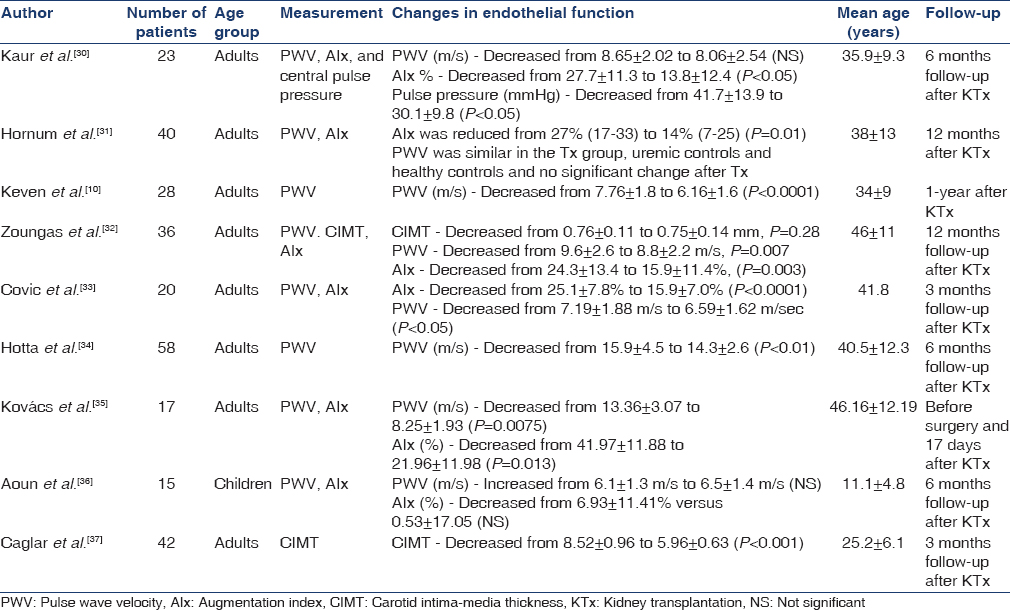

The techniques used to measure arterial stiffness include measurement of arterial pulse wave velocity (PWV) and AIx. There have been a few studies that prospectively analyzed the effects of KTx on PWV in CKD patients [Table 3].

Our literature search found eight studies that prospectively assessed PWV before and after KTx. These studies encompassed a total of 237 patients of which 15 were children, and the remaining were 222 adults. The average age ranged from 11 ± 5 years in children to 46 ± 12 years in adults.

There were six studies that analyzed the AIx before and after KTx. These included a total of 151 patients, of which there were 15 children and 136 adults. Five out of these six studies showed a significant decrease in AIx post-KTx.[303132333536]

Seven studies showed a reduction in post-KTx PWV when compared to pretransplantation. However, five of these demonstrated a significant difference.[1032333435] Of the remaining two studies, both showed nonsignificant changes but one study actually showed an average increase in PWV after KTx.[3136]

The largest reduction in PWV post-KTx was observed by Kovács et al., who showed an average decrease of 5.1 m/s in 17 patients.[35] Kovács also showed a significant reduction of 48% in AIx posttransplantation from 42% ± 12% to 22% ± 12% (P < 0.05). Interestingly, this was also the study with the smallest patient size. Even more strikingly, this change was seen just 17 days after the transplantation. In contrast, the study with the longest follow-up time by Zoungas et al., showed a reduction in PWV of only 1.2 m/s, (P = 0.007) and a 33% reduction in AIx in 36 patients, 12 months after KTx.[32] In addition, the largest study by Hotta et al., conducted on 58 patients showed a reduction in PWV of 1.6 m/s (P < 0.01) at a follow-up period 6 months post-KTx.[34]

Only one of the seven studies looking at PWV involves children and when comparing this to the adult studies, a difference was noted. This study on 15 children, conducted by Aoun et al., observed an increase in PWV of 0.5 m/s after KTx; however, it was not found not to be significant. In addition, the change in AIx posttransplant was also not noted to be significant.[36] In contrast, every study on adults found a reduction in PWV posttransplantation. Due to lack of prospective PWV studies on children, we are unable to comment on whether really there is a difference between the changes in PWV in adults compared to children following KTx. This is, therefore, a potential for further research.

Endothelial function

Endothelial function assessment includes measuring endothelial dependent dilation either from analyzing brachial artery FMD or following angiography with acetylcholine infusion. Measurement of endothelial function has also be assessed by nitroglycerin induced dilatation (NID) and endothelial progenitor cell migration (EPC).

There is increasing evidence to show that the endothelial function improves following renal transplantation. Table 4 summarizes the changes in endothelial function in CKD patients following KTx.

There were eight studies found during the literature search that spanned across the years 2003–2014. In total, 383 patients were assessed, of which all were adults. The age range of patients varied from 25 ± 6 years to 40 ± 3 years. Follow-up intervals ranged from 14 days to 12 months after KTx. Out of the eight studies, seven assessed endothelial dependent dilation: Six with FMD and one with acetylcholine administration. The remaining study assessed endothelial function by analyzing EPC migration to mature endothelial cells. NID was assessed alongside five of the six FMD studies. The largest study was conducted by Yilmaz et al., who assessed a cohort of 161 patients.[42] In contrast, the smallest sample study was conducted by Passauer et al., in which eight patients were assessed.[45]

All eight studies showed some degree of improvement in endothelial function. In five out of six studies assessing FMD and three out of the five studies assessing NID, significant improvements were observed following KTx. In addition, the one study looking at endothelial dependent dilation via acetylcholine administration also showed a significant improvement after KTx.[45] Finally, KTx was also found to increase EPC migration by approximately two-fold.[43]

One of the biggest changes in FMD was observed by Sharma et al., in which 60 Indian patients were assessed before and 3 months after KTx.[25] The study showed an improvement in FMD from 9.1% to 15.7% following KTx. In addition, impaired FMD, defined as FMD <4.5%, was present in 26.8% of CKD patients pretransplant and 3.3% of patients posttransplant.[25] Thus, indicating that KTx can reverse endothelial dysfunction in CKD patients. Interestingly, however, there was no significant improvement in NID in the cohort of 60 patients posttransplantation. In contrast, the opposite was observed in a study by Hornum et al. in which both FMD and NID were assessed in 40 hemodialysis patients. The study found that NID improved significantly from 11% to 18% posttransplant; however, no significant difference was noted in the FMD.[31] Reasons for the variations in observations are difficult to explain but could be due to varied sample sizes and differences in patient characteristics.

Comparatively, the study by Yilmaz et al. was conducted on a larger sample of 161 chronic hemodialysis patients receiving KTx. At 6 months posttransplant, there was a significant improvement of 1.4% in FMD from 5.2% ± 0.8% to 6.6% ± 0.8% (P < 0.001) as well as a significant improvement of 0.6% in NID from 11.9% ± 0.9% to 12.5% ± 0.7% (P < 0.001).[42] In addition to improved vascular function, this study also showed a parallel improvement in the FGF23, serum phosphorus, and 25 (OH) Vitamin D levels. Thus, highlighting a potential link between improvement of CKD-mineral bone disease and reduction in cardiovascular risk.[42]

The study with the shortest follow-up time was conducted by Kocak et al., who assessed FMD in 30 patients 3 days before and 14 days after KTx. The study found a 57% improvement in FMD, from 6.7% to 10.5%, posttransplantation (P < 0.001).[46] In comparison, Oflaz et al. followed up patients both at 6 months and 12 months after KTx. The study found that FMD improved from baseline (5.6%) at both 6 months (8.3%) and continued to improve at 12 months (12.1%).[44] Hence, a total improvement of 116% posttransplantation. This indicates that KTx potentially result in a sustained improvement in FMD and thus, improve atherosclerosis in long-term, which needs further research.

An interesting question is whether there is a difference in endothelial function between the preemptive and dialysis patients, post-KTx. Sharma et al. found that CKD patients with GFR of <15 had poorer average FMD (8.8%) compared with those patients who had a GFR of 15–60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (12.9%).[25] Potential research could, therefore, help identify whether KTx has a more beneficial effect on endothelial function in predialysis versus dialysis patients.

Finally, no prospective studies assessing endothelial function in children were found during our literature search. This is another area for further research in order to establish the effect of KTx on endothelial function in children.

Risk factors and pathophysiology

The heightened cardiovascular event rates in the CKD population have been predominantly attributed to atheromatous and nonatheromatous vascular disease. Traditional risk factors, though frequently present do not fully explain this increased risk in the CKD population. Interestingly, the nontraditional risk factors such as inflammation, oxidative stress, abnormalities of calcium, phosphate and PTH balance, as well as Vitamin D deficiency and anemia are increasingly being recognized as causes of the high cardiovascular event rates.[47]

The vascular changes related to the improvement in uremic milieu are not very well known, however, may be attributed to improvements in the inflammatory profile. Inflammation contributes to chronic dysregulation of nitric oxide in vascular smooth muscle, and hence, results in endothelial dysfunction; the consequence of which is vessels being at risk of becoming proatherogenic.[4849] Down regulation of inflammatory pathways and intercellular adhesion molecules responsible for the endothelium-leukocyte interaction, could contribute to the improved nitric oxide generation and endothelial function following KTx.

LVH is caused by inflammation, fibrosis, and increased afterload. In addition, anemia and fluid overload results in left ventricular dilation with LVH and the resulting structural abnormalities contribute to both systolic and diastolic dysfunction.[50] A large proportion of the studies discussed in this review show regression of LVH and improvement of cardiac function following KTx. More recent research has found a relationship between endothelial dysfunction and LVH.[51] We propose that improvement in LVH may be related to improvement in endothelial dysfunction.

Conclusion

There is substantial evidence to show that KTx results in a reduction in LVH. There is some evidence to suggest an improvement of cardiac function in CKD patients following KTx. There is a lack of prospective research assessing the effect of KTx on vascular structure, especially CIMT. There is increasing evidence describing the improvement of endothelial function in CKD patients following KTx in adults; however, further research is required in children.

This review highlights the changes in cardiovascular structure and function following KTx; however, further research is necessary to establish the vascular changes, as well as to investigate the mechanisms behind these changes.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chronic kidney disease: Effects on the cardiovascular system. Circulation. 2007;116:85-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1296-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associations of kidney disease measures with mortality and end-stage renal disease in individuals with and without diabetes: A meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380:1662-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- CKD and cardiovascular disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: Interactions with age, sex, and race. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:691-702.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 cliniical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1-150.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney transplantation halts cardiovascular disease progression in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1662-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute myocardial infarction and kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:900-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular complications after renal transplantation and their prevention. Transplantation. 2006;82:603-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved left ventricular mass index in children after renal transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2008;23:1545-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative effects of renal transplantation and maintenance dialysis on arterial stiffness and left ventricular mass index. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:360-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in left ventricular mass index in children and adolescents after renal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2001;5:279-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac consequences of renal transplantation changes in left ventricular morphology. Rev Port Cardiol. 1998;17:145-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term changes in left ventricular hypertrophy after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;70:570-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early echocardiographic changes and survival following renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15:93-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of renal transplantation on uremic cardiomyopathy. Transplantation. 1995;60:908-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Course of left ventricular hypertrophy and function in end-stage renal disease after renal transplantation. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70:1481-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphologic course of the left ventricle after renal transplantation. Echocardiographic study. Rev Port Cardiol. 1991;10:497-501.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac consequences of renal transplantation: Changes in left ventricular morphology and function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;12:915-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of renal transplantation for chronic renal disease on left ventricular mass. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:254-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of renal transplantation on left ventricular size and function. Br Heart J. 1982;47:155-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Echocardiographic changes after successful renal transplantation in young nondiabetic patients. Chest. 1983;83(1):56-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular effects of successful renal transplantation: a 30-month study on left ventricular morphology, systolic and diastolic functions. Transplant Proc. 2005;37(2):1039-1043.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular effects of successful renal transplantation: a 1-year sequential study of left ventricular morphology and function, and 24-hour blood pressure profile. Transplantation. 2002;74(11):1580-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of echocardiographic alterations in the first six months after kidney transplantation. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;98:505-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of endothelial dysfunction in Asian Indian patients with chronic kidney disease and changes following renal transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2014;28:889-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of successful kidney transplantation on ventricular dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3524-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of kidney transplant on cardiac function: An echocardiographic perspective. Echocardiography. 2001;18:457-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early and late effects of renal transplantation on cardiac functions. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2680-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Left ventricular function before and after kidney transplantation. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:821-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal transplantation normalizes baroreflex sensitivity through improvement in central arterial stiffness. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2645-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney transplantation improves arterial function measured by pulse wave analysis and endothelium-independent dilatation in uraemic patients despite deterioration of glucose metabolism. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2370-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arterial function after successful renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1882-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful renal transplantation decreases aortic stiffness and increases vascular reactivity in dialysis patients. Transplantation. 2003;76:1573-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful kidney transplantation ameliorates arterial stiffness in end-stage renal disease patients. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:684-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Noninvasive perioperative monitoring of arterial function in patients with kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:3682-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aortic stiffness in ESRD children before and after renal transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1331-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endothelial dysfunction and fetuin A levels before and after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;83:392-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term impact of renal transplantation on carotid artery properties and on ventricular hypertrophy in end-stage renal failure patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:645-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on structural changes of the carotid arteries and the heart in asymptomatic renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:160-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of arterial structure and function in pediatric patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis and after renal transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:480-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endothelial dysfunction, inflammation and atherosclerosis in chronic kidney disease – A cross-sectional study of predialysis, dialysis and kidney-transplantation patients. Atherosclerosis. 2011;216:446-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Longitudinal analysis of vascular function and biomarkers of metabolic bone disorders before and after renal transplantation. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37:126-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney transplantation substantially improves endothelial progenitor cell dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal disease. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2922-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in endothelial function before and after renal transplantation. Transpl Int. 2006;19:333-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney transplantation improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in patients with endstage renal disease. Transplantation. 2003;75:1907-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of renal transplantation on endothelial function in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:203-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiovascular complications of chronic kidney disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:4-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endothelial function and dysfunction: Testing and clinical relevance. Circulation. 2007;115:1285-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: A statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Hypertension. 2003;42:1050-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Left ventricular hypertrophy and endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:56-61.

- [Google Scholar]