Translate this page into:

Lymphoblastic lymphoma presenting as bilateral renal enlargement diagnosed by percutaneous kidney biopsy: Report of three cases

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Renal involvement by lymphoma can be a diagnostic challenge. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is an unusual manifestation of lymphomatous infiltration in the kidneys. We report three cases of lymphoblastic lymphoma, a very rare form of lymphoma, presenting with AKI and bilateral enlargement of kidneys, diagnosed by percutaneous kidney biopsy. Lymphomatous infiltration should be suspected with such clinical presentation. Kidney biopsy is a valuable diagnostic tool, to establish the correct diagnosis and subtype of lymphoma for timely initiation of therapy for these aggressive hematological malignancies.

Keywords

Acute kidney injury

kidney biopsy

lymphoblastic lymphoma

renal lymphoma infiltration

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)/lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) is a neoplasm of lymphoblasts committed to either T-cell or B-cell lineage and involving bone marrow and blood as defined by World Health Organization classification[1] By convention, the term lymphoma is used when the process is confined to a mass lesion with no/minimal evidence of peripheral blood and bone marrow involvement. The term leukemia is used when there is extensive peripheral blood and bone marrow involvement. LBL accounts for approximately 2% of all lymphomas and arises from immature T-cells in 80–90% and from immature B-cells in the rest.[2] Both subtypes of LBL/ALL are morphologically similar on light microscopy (LM) and require immunophenotyping for differentiation.

LBL can be an extra-nodal disease, with a propensity to involve mediastinum skin, bone, liver, spleen, testis, and central nervous system.[1] Kidney as a sole site of involvement is extremely rare; fewer than 50 cases of lymphoma diagnosed by percutaneous kidney biopsy have been reported.[3] Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common subtype reported and precursor LBL/ALL accounts for very few cases.[345] We report three cases of precursor LBL diagnosed by kidney biopsy. Our cases highlight two unusual manifestations of LBL and renal involvement namely acute kidney injury (AKI) and bilateral diffuse enlargement of kidneys.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 22-year-old male presented with backache of 4 months duration. He was normotensive. He appeared pale; there was no hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy. Hemoglobin was 6.5 g/dl, TLC was 9400/mm3. He had 3 + proteinuria and creatinine of 8.4 mg/dl. Ultrasound abdomen reveal bilaterally, markedly enlarged kidneys, right 18 cm and left 20 cm [Figure 1]. Renal biopsy was performed.

- Magnetic resonance imaging showing bilaterally enlarged kidneys (Case 1)

Histopathological examination revealed diffuse monotonous interstitial lymphoid infiltrate replacing and widely expanding the cortical tissue. The cells had relatively round and uniform nuclei, showed prominent apoptosis and mitotic activity. IF was negative for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, kappa, and lambda light chains. IHC showed that the neoplastic cells were strongly and diffusely CD3 positive with only occasional CD20 positive cells. The cells were also positive for TdT, CDd4, CD8, and CD10. A small subset of cells was positive for CD34. CT scan done subsequently showed enlarged mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Bone marrow examination did not reveal atypical lymphocytes. The pathological findings were consistent with T-LBL, stage IV.

He was referred to an Oncology Centre for further management but was lost to follow-up.

Case 2

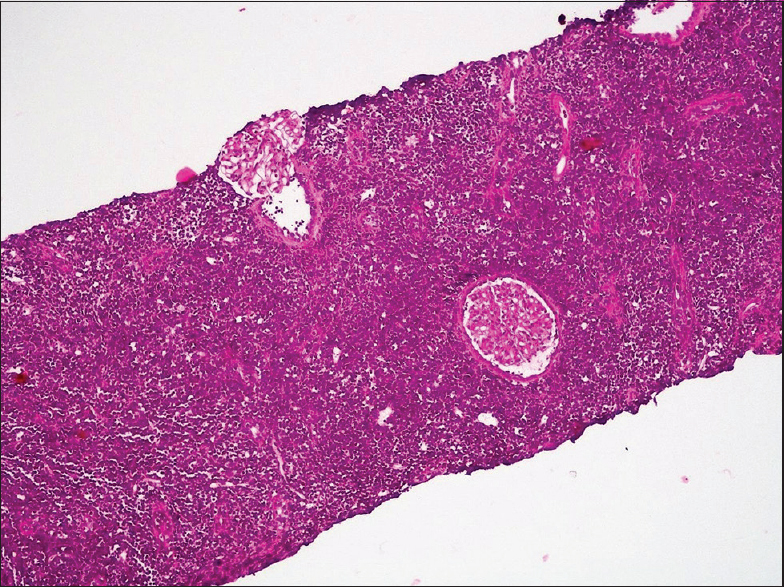

A 27-year-old man presented with breathlessness and vomiting. He was non-oliguric and had no contributory medical history. His blood pressure was 180/110 mmHg. Investigations showed BUN 120 mg/dl, creatinine 14 mg/dl, TLC 14,000/mm3, hemoglobin 11 g/dl, and platelets 1.97 lakhs/mm3. Peripheral blood smear showed normocytic normochromic anemia and presence of lymphoblasts, trace proteinuria was detected, serum corrected calcium was 9.7 mg/dl, lactate dehydrogenase was 486 U/L and uric acid 14 mg/dl. Viral serology for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV 1 and 2 were negative. Bone marrow examination confirmed ALL L2 morphology pre-B in subtype. Flow cytometry showed that blasts were positive for CD19/20/22/10/79a and TdT. There was aberrant expression of CD13. Chest radiograph was normal. Ultrasound abdomen showed bilateral diffusely enlarged echogenic kidneys with right kidney 14 cm and the left kidney 13.2 cm. Percutaneous kidney biopsy was performed after few sessions of hemodialysis. Histopathology showed sheets of tightly packed, monotonous lymphocytes, which obliterated the renal parenchyma but spared glomeruli. [Figure 2] The lymphocytes showed high mitotic and apoptotic activity. IF was negative for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, kappa, and lambda light chains. Immunoperoxidase stains for CD20 and CD3 showed that 99% of the cells were CD20 positive and only scattered cells were CD3 positive indicating B-cell lineage. The neoplastic lymphoid cells were strongly positive for CD10, TdT, Bcl2, and Ki67. A subset of cells was weakly positive for Bcl6. They were negative for CD34. The diagnosis of precursor B-LBL/leukemia was made further imaging studies with CT abdomen showed a few small retroperitoneal nodes. CT chest revealed mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Treatment could not be given because he succumbed to infection complicated by renal failure.

- Renal biopsy of Case 2: Lymphoid cells diffusely infiltrate the renal parenchyma. H and E, ×100 (Case 2)

Case 3

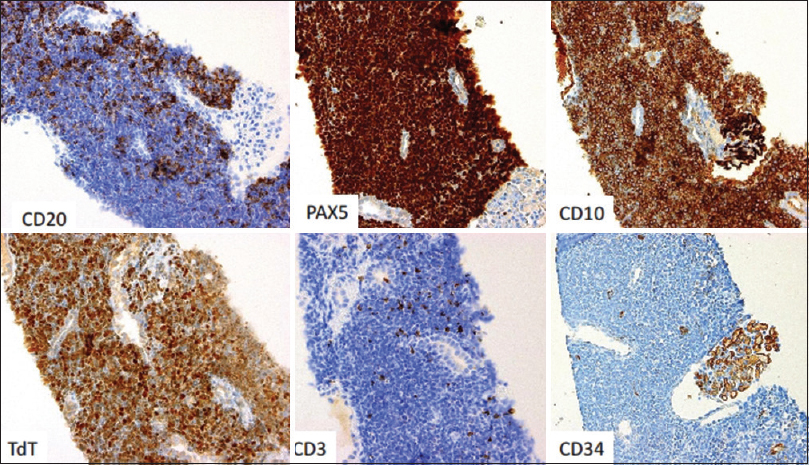

A 12-year-old girl presented with 2 months history of low grade intermittent fever and arthralgia. She was pale, normotensive with no significant lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. Investigations showed blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 12 mg/dl, creatinine 1.3 mg/dl, total white blood cell count (TLC) 6600/mm3, hemoglobin, 10 g/dl and platelets, 2.6 lakhs/mm3. Peripheral smear showed microcytic hypochromic anemia. There was no proteinuria, serum corrected calcium was 9 mg/dl, lactate dehydrogenase 135 U/L, and uric acid 6 mg/dl. Viral serology for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV 1 and 2 were negative. Chest radiograph was normal. Ultrasound showed bilateral diffusely enlarged echogenic kidneys with right kidney 11.8 cm and left kidney 12 cm. Computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral enlarged kidneys with a solitary para-aortic node measuring 1.4 cm. CT chest was normal. Percutaneous kidney biopsy was performed. Histopathology showed renal parenchyma with diffuse infiltration of intermediate sized cells that obliterate majority of the renal architecture. Only rare tubules and morphologically normal glomeruli were observed. The cells displayed large nuclei with scant cytoplasm. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining was negative for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, kappa, and lambda light chains. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) were positive for CD20, PAX5 (strongly and diffuse), CD10 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and negative for CD3 and CD34 [Figure 3]. Bone marrow examination of this patient did not reveal any atypical cells. These findings are diagnostic of precursor B-LBL stage IV. She was started on chemotherapy but developed septicemia and succumbed to the overwhelming infection.

- Lymphoma cells strongly express CD20, PAX5, CD10 and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase. They are negative for CD3 and CD34, confirming the diagnosis of precursor B-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (Case 3)

Discussion

The first description of lymphoma diagnosed by percutaneous biopsy was published in 1980 by Coggins.[6] Since then fewer than 50 cases have been reported in the literature.[3] There seems to be a variation in clinical presentation of the subtypes of lymphomas. B-cell LBL frequently involves the skin, bone, soft tissue, lymph nodes, ovaries, retroperitoneum, and tonsils. On the other hand, T-cell LBL usually presents as a mediastinal mass or with lymphadenopathy in cervical, supraclavicular, and axillary regions. Renal involvement by lymphomatous cells occurs in 30–40% of cases of lymphoma.[789] It usually occurs late in the course of the disease and is clinically silent.[10] Very few cases have been reported in the literature of LBL diagnosed by kidney biopsy.[345]

Precursor B LBL/ALL is morphologically indistinguishable from precursor T LBL/ALL on LM, but differentiation is based on the expression of lineage specific markers.[11] Two of our three cases were diagnosed to have precursor B-LBL and one had T-LBL.

AKI due to lymphomatous infiltration is quite rare and in a series of 48 patients with aggressive lymphomas with renal involvement, only three patients had AKI as the presenting feature.[12] All three patients reported here presented with AKI. Other causes of renal failure in lymphoma include ureteric obstruction, hypercalcemia, urate nephropathy, sepsis, radiation nephritis, and paraproteinemia.[13] None of our three patients had any features of the above factors. The mechanism of renal failure when lymphoma infiltrates the kidneys has not been fully explained. There is an increase in interstitial pressure due to tumor infiltration which causes tubular obstruction, compression of peritubular capillaries, and alteration in the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism.[14] A case of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma presenting with polyuria, in addition to renal insufficiency with enlarged kidneys, has also been reported.[15]

The clinical suspicion of lymphomatous infiltration should arise when patients present with unexplained AKI and/or bilateral nephromegaly. While other causes of increased renal size can be considered, a definitive diagnosis requires a kidney biopsy. The indications for biopsy in previous case reports were unexplained renal failure or proteinuria except for few cases where the indication was bilateral nephromegaly detected on radio imaging.[3] All our three patients had bilateral nephromegaly; two were biopsied for unexplained renal failure and the third patient was biopsied for diffuse bilateral enlargement of the kidneys suggestive of infiltrative disease.

Radiographic interpretation of renal lymphoma is difficult and needs skill and experience. Contrast enhanced CT is the preferred method for diagnosing renal lymphoma, but has the disadvantage of nephrotoxicity.[1617] Recently, magnetic resonance imaging has been proposed to be superior, especially in patients with renal failure, in diagnosis of lymphoma.[5]

Two of the three cases in our series were suspected to have infiltrative disease based on sonographic findings. Plain CT abdomen narrowed the diagnosis toward lymphoma mainly based on the retroperitoneal lymph node involvement in one case and in the remaining two cases, CT abdomen was done only after the histological diagnosis to assess the extrarenal involvement. Extrarenal involvement at the time of biopsy or shortly after that has been described in around 44% of the lymphoma cases diagnosed through kidney biopsy in the literature.[3] All our three cases had extrarenal involvement evidenced by imaging studies.

Renal involvement by lymphoma can be of intraglomerular type[18] or interstitial type as in all our three cases. Intraglomerular lymphoma appears as endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis, requiring IHC for confirmation.[19]

The treatment of choice is systemic chemotherapy using a CHOP regimen. Median survival is usually <1 year,[20] but the addition of rituximab to the combination chemotherapy has improved the survival rate.[21] Two of our patients died, within 6 months of diagnosis, due to overwhelming infection. The third patient is lost to follow-up.

Conclusion

Lymphomatous infiltration of the kidneys should be considered as a differential diagnoses in patients presenting with AKI and bilateral diffuse enlarged kidneys. A low threshold for percutaneous kidney biopsy is needed to establish early diagnosis. Therapy options exist but prognosis remains poor.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- T lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. In: Swerdlow S, Campo E, Lee Harris N, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. p. :168-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A separate entity? Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9(Suppl 3):S214-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphomas diagnosed by percutaneous kidney biopsy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:960-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia as a cause of a bilateral nephromegaly. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:679-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute kidney injury and bilateral symmetrical enlargement of the kidneys as first presentation of B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:1044-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Precursor B-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. A study of nine cases lacking blood and bone marrow involvement and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115:868-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinico-biological features of 5202 patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia enrolled in the Italian AIEOP and GIMEMA protocols and stratified in age cohorts. Haematologica. 2013;98:1702-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal lymphoma: Radiologic-pathologic correlation of 21 cases. Radiology. 1982;144:759-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunophenotype of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia, clinical parameters, and outcome: An analysis of a prospective trial including 562 tested patients (LALA87).French group on therapy for adult acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Blood. 1994;84:1603-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aggressive lymphomas with renal involvement: A study of 48 patients treated with the LNH-84 and LNH-87 regimens. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Br J Cancer. 1994;70:154-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure due to lymphomatous infiltration of the kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1348-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma presenting with polyuria and acute renal insufficiency. Ren Fail. 1995;17:165-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal lymphoma: Spectrum of CT findings and potential mimics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1067-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Further evidence that “malignant angioendotheliomatosis” is an angiotropic large-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:943-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- A case of non-Hodgkin lymphoma presenting primarily with renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:535-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure due to a malignant lymphoma infiltration uncovered by renal biopsy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2657-60.

- [Google Scholar]