Translate this page into:

Post Renal Transplant Collapsing Glomerulopathy is Associated with Poor Outcomes

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Collapsing glomerulopathy (CG) is a distinct morphologic pattern of proliferative renal parenchymal injury. It differ from focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) by clinicopathologic pattern and its adverse outcome. The clinical significance of CG in renal allograft biopsies is not yet clear due to scant data and less occurrence of CG in renal transplant recipients. We conducted this single-center retrospective study to evaluate the prevalence, clinicopathological features, and outcome of post renal transplant CG.

Subjects and Methods:

We studied 127 renal allograft biopsies performed over a period of 45 months (Jan 2015–Oct 2018). A diagnosis of CG was made if at least one glomerulus demonstrated global or segmental collapse of the glomerular capillary walls, associated marked hyperplasia, and hypertrophy of the overlying visceral epithelial cells. We analyzed clinical, biochemical, and pathological characteristics and its impact on renal allograft outcome. Statistical analysis was performed and continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians (interquartile range and noncontinuous data were expressed in percentage and numerical values.

Results:

The prevalence of CG was 5.3% (7/127) of allograft biopsies. Out of the seven patients, six patients had undergone live donor transplant and one patient had undergone deceased donor renal transplant. The native kidney disease was unknown in these patients except one (IgA nephropathy). The median duration of diagnosis for CG was 17 months after transplantation (range 5–132months). Presenting symptoms were pedal edema and hypertension in 71.4% (5) patients each. All patients had proteinuria of more than 1 gm and renal allograft dysfunction and median serum creatinine of 3.05 mg/dl (1.5–4.8 mg/dl). All patients received standard triple immunosuppression. Over a period of 2–20 months, 57.14% (4) patients developed a graft failure and 43% (3) of the other patients had functioning grafts with serum creatinine of 1.5–4.2 mg/dl.

Conclusions:

CG presents with moderate to severe proteinuria and may lead to rapid graft dysfunction and subsequent graft failure in most of the patients.

Keywords

CG-collapsing glomerulopathy

CNI-calcineurin inhibitors

GD-graft dysfunction

GF-graft failure

Introduction

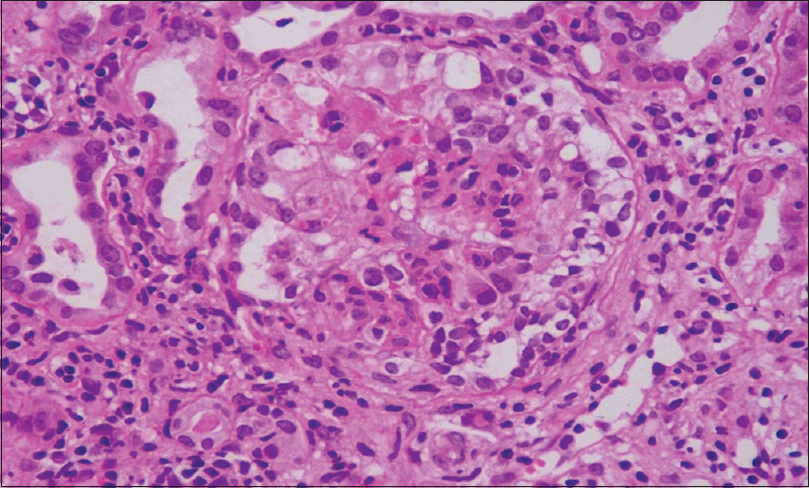

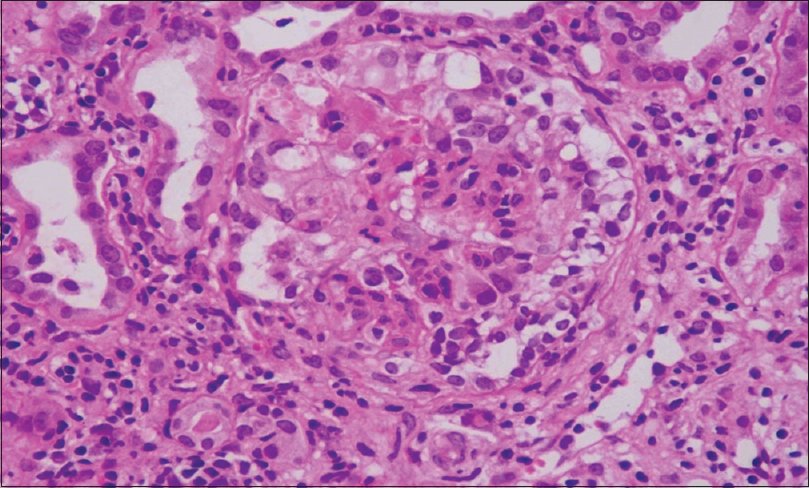

Collapsing glomerulopathy (CG) was first described by Weiss et al.[1] as a distinct variant of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) with progressive renal failure and pathological changes characterized by segmental or global capillary collapse [Figure 1], visceral epithelial cell hypertrophy, and hyperplasia with hyaline droplets and extensive tubulointerstitial inflammation [Figure 2].[2] CG, initially, was recognized as a variant of FSGS, especially associated with HIV infection. Recent studies suggest that CG is a distinct clinicopathologic entity not related to FSGS due to differences in the clinical presentation, histologic appearances, and outcome. We conducted this single-center retrospective study to evaluate the prevalence, clinicopathological features, and outcome of post renal transplant collapsing glomerulopathy.

- Renal biopsy H and E stain: Renal allograft biopsy showing collapse of the glomerular tuft

- Renal biopsy pas stain: Renal allograft biopsy showing collapse of the glomerular tuft with tubular injury

Subjects and Methods

We analyzed renal allograft biopsies performed in our department over a period of 45 months (Jan 2015–Oct 2018). All biopsies were performed by nephrologists under ultrasound guidance using a spring-loaded 16 gauge biopsy gun under local anesthesia (LA). All the biopsy slides were examined by a single pathologist. Renal biopsy tissues were processed for light microscopy, 3 μm thick paraffin sections were stained for hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff (PAS), and Gomori's trichrome stains. Cryostat frozen sections were subjected to interstitial fibrosis (IF) studies and electron microscopy was not performed due to logistic reasons. In addition, C4d were tested by immunohistochemistry using polyclonal antihuman C4d antisera, and the grading and identification of the cellular or antibody rejection were conducted according to the Banff classification. Serological investigations for viral infections (HIV, hepatitis B [HBV], and hepatitis C [HCV]) were also carried out. Institutional Ethical Committee approval obtained.

Clinical data were obtained from a review of the patients' medical records. Their records were reviewed for clinical features, biochemical, pathology and serology reports. Follow-up details were noted. During the study period, seven such biopsies were identified.

A diagnosis of CG was made if at least one glomerulus demonstrated these typical changes.

-

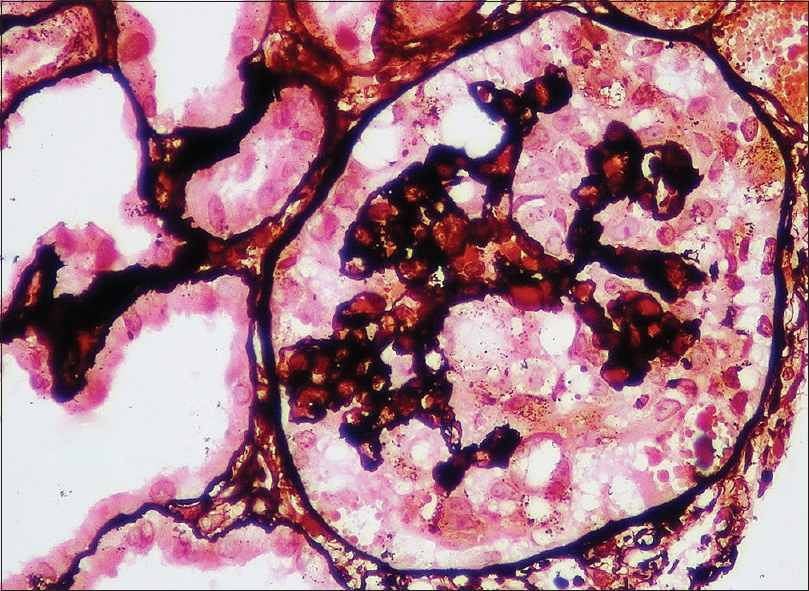

The global or segmental collapse of the glomerular capillary walls was associated with implosive wrinkling and retraction of the glomerular capillary wall [Figure 3]

-

Marked hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the overlying visceral epithelial cells

-

Severe tubular injury along with microcystic tubular dilatation and prominent intracytoplasmic PAS +ve protein reabsorption droplets.

- Renal biopsy pas-silver stain: Renal allograft biopsy showing collapse of the glomerular tuft

According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guidelines, all recipients received standard triple-drug immunosuppression (Cyclosporine one and Tacrolimus in six). Statistical analysis was performed and continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians (interquartile range andnoncontinuous data were expressed in percentage and numerical values).

Results

A total of 127 renal allograft biopsies were performed over a period of 45 months. Of these, seven showed features of CG, constituting 5.51% of all allograft biopsies. Six patients received allografts from living related donors (mother 3, father 1, sister 1, and spouse 1), except one from a deceased donor. Both males (4) and females (3) were almost equally affected. The mean age of patients was 39 ± 7.5 years, from which the mean age of males was 44.5 ± 3.1 years and of females was 31.6 ± 4.1 years. All patients had an insidious onset of proteinuria with concomitant graft dysfunction for which allograft biopsy was done. Of the seven patients, five presented with pedal edema. The median time of presentation following renal transplant was 17 months (range 5–132 months) [Table 1]. The median time to biopsy from symptom onset was 14 day (range 5–32 days).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) Sex | 43/F | 35/M | 33/F | 27/F | 44/M | 49/M | 42/M |

| Time of biopsy from transplant (months) | 48 | 16 | 132 | 17 | 5 | 32 | 14 |

| Indication for biopsy | GD | GD pedal edema | GD pedal edema | GD | GD pedal edema | GD pedal edema | GD pedal edema |

| Hypertension (>140/90) | + | + | + | + | - | + | - |

| Urine protein 24 h (g/day) | 1.7 | 3.1 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 5.9 | 5.1 |

| S. Cr. (mg/dl) | 1.9 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 3.5 | 1.5 | 2.6 | 1.6 |

| Follow-up (months) | 9 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 20 | 1 | 1 |

| Outcome (S. Cr, mg/dl) | 1.6 | GF | GF | GF | 1.9 | GF | 1.5 |

GD: Glomerular disease, S. Cr.: Serum creatinine

The native kidney disease was unknown in these patients, except in one (IgA nephropathy). All the patients had proteinuria more than 1 gm/day with 24 h urine protein ranging between 1.2 and 5.9 g/day of which three patients had nephrotic proteinuria but classical nephrotic syndrome was unseen. Serum calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) trough levels were within expected ranges in all the patients except one. New onset of hypertension was observed in three patients and two had preexisting hypertension. Two patients had HCV infection after renal transplant, who were treated with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir for 12 weeks. Serology for HBV, HIV, CMV, Parvovirus DNA PCR, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for BK virus done were negative for all recipients [Table 1].

The mean number of glomeruli in this biopsy specimen was 13.1 ± 5.6. All the biopsies had one or more (20.18%) glomeruli, showing a segmental collapse of the tuft with swollen hypercellular podocytes overlying the collapsed tuft. Mild to marked arteriolar hyalinosis was noted in four cases (57.1%). Of the seven biopsies, one showed coexisting chronic active cellular rejection and another one had histological features suggestive of CNI toxicity [Table 2]. Immunofluorescence staining with IgA, IgG, IgM, C3, C1q, Kappa, and Lambda, including C4d, performed in all cases, and all stains were negative.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of glomeruli | 8 | 8 | 23 | 19 | 11 | 11 | 12 |

| Global sclerosis (%) | 4 (50%) | 1 (13%) | 10 (44%) | 6 (32%) | - | 4 (37%) | 6 (50%) |

| Segmental collapse (%) | 2 (25%) | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (13%) | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (9%) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Other glomerular injuries | Hyaline globules + | BK stain −ve | SG 3 | SG 5 | - | Periglom fibrosis 3 | |

| IF/TA | 10-20% | 40% | 40% | 30-35% | - | 60% | <10% |

| Acute/chronic rejection | - | - | - | - | - | Chronic ACMR | - |

| Arteriolar hyalinosis | + | + | + | + | - | - | - |

IF/TA: Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy

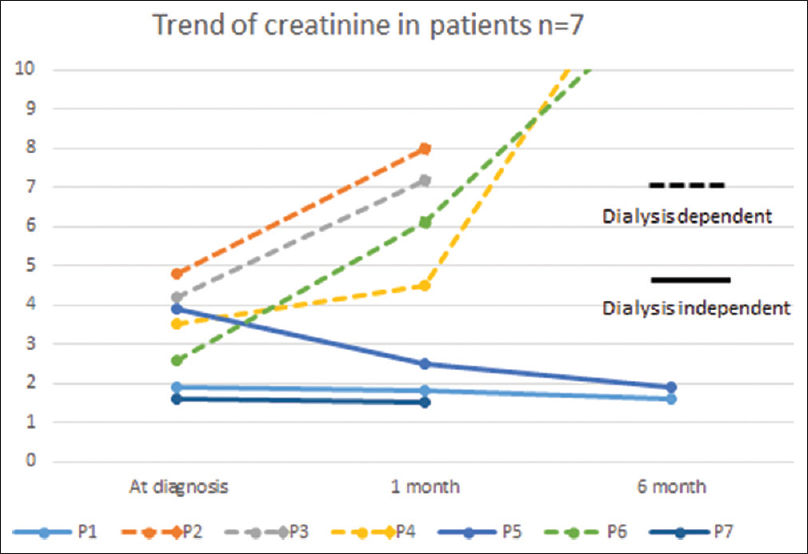

We did not attempt any experimental therapeutic interventions, such as plasma exchange or rituximab. Tacrolimus dose was adjusted to achieve a C0 tacrolimus level of 3–5 ng/mL. Angiotensin receptor blockers at maximum tolerated dose were also prescribed. The follow-up details were in seven patients at a mean duration of 7 months (1–20 months). At the end of the follow-up period, four patients (57.14%) had graft failure (S. creatinine >5 mg/dl or return to dialysis) while the other three patients had functioning grafts with serum creatinine ranging between 1.5 and 4.2 mg/dl.

Discussion

CG was initially described as “malignant FSGS” in 1978 due to the clinical presentation of rapidly progressive nephrotic syndrome.[2] Thirty-five years ago, this morphologic pattern of diagnosis typically is seen in the setting of HIV infection.[3] In 1986, Wiess et al. described HIV-positive patients with proteinuria, who showed features of collapsing glomerulopathy,[1] and in 1988, Cohen and Nast elaborated the morphological features of segmental tuft collapse with overlying podocyte hypertrophy and hyperplasia along with microcystic tubular dilatation with inspissated proteinaceous material and extensive protein resorption droplets within proximal tubular epithelium.[4]

Collapsing FSGS is a distinct variant of FSGS that may occur in HIV-infected individuals or in an idiopathic form. In 1994, Detwiler et al. reported 16 predominantly African-American, HIV-negative patients and suggested it was a variant of FSGS.[5] Subsequently, others corroborated these results and with a larger study by Valeri et al., the term collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis was introduced in the literature.[6] CG is now recognized as a, distinct pattern of proliferative parenchymal injury that portends a rapid loss of renal function and poor responses to empiric therapy.[7] Both recurrent and de novo CG with features similar to these have been described in allograft recipients, usually, presenting within 25 months after transplantation.[89] Our study showed CG in the allograft biopsy at a median of 17 months after transplantation (range 5–132months). Similarly, other reports showed that CG in allograft can occur in anytime from 5 to 98 months after renal transplantation.[101112] In the present study, the overall prevalence of CG was 5.5%, which is higher compared to other studies. One of the studies reported a similar frequency of 3.2%,[10] other studies reported an overall prevalence is 0.6–0.83%,[1314] which shows an increasing awareness in recent years. All the patients had proteinuria more than 1 gm (1.2–5.9 g/d), three of them had the nephrotic range and the serum creatinine was 1.5–4.8 mg/dl and other reported studies show similar results [Table 3].[1011121314]

| Present study 2015-18 | Kanodia et al.[14] 2007-15 | Gupta et al.[10]2008-09 | Meehan et al.[13] 1993-97 | Stokes et al.[11] 1988-98 | S.Swaminathn et al.[12] 1994-2003 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of Patients | 7 | 21 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 10 |

| Prevalence (%) | 5.51 | 0.83 | 3.5 | 0.6 | - | - |

| Age (years) | 39±7.59 | 35±3.65 | 32.4±11.2 | 31±66 | 23±55 | 37±9.7 |

| Duration (months) | 5-132 | 1.4-101 | 12-98 | 6-25 | 18-144 | 1.2-7.2 |

| Sr.Cr. (mg/dl) | 1.5-4.8 | 1.06-4.31 | 1.6-5 | - | 3.4-9.4 | 4.2±2.6 |

| U.protein g/d | 1.2-5.9 | 1.09-7.14 | 2.5-5.8 | 1.8-11.8 | +1-+4 | 11.9±6.8 |

| Follow-up (months) | 5-22 | 5-46 | 3-12 | 6-30 | 3-16 | 36 |

| Graft failure (%) | 57.14 | 52.38 | 50 | 100 | 72 | 100 |

S. Cr.: Serum creatinine

The exact pathogenic mechanism of CG in renal allograft has not been described until now, but various post-transplant factors, such as immunosuppressive medication, immunological injury, microvascular disease and infection, medication (IFN and Peg IFN) are believed to be involved in pathogenesis. AT1-receptor AB-mediated pathway may contribute not only to antibody-mediated rejection but also to de novo CG.[15] Nadasdy et al. observed the zonal distribution of glomerular collapse in three allograft nephrectomies with obliterative vascular changes.[16] Meehan et al. reported that the role of CNI induced hyaline arteriosclerosis and ischemic changes in the development of CG.[13] We also observed associated CNI toxicity in one patient. Graft dysfunction may be due to the acute rejection and immune complex glomerulopathy in CG.[10111213] We observed a case of CG with rejection (Chr. ACMR). In this present series, out of the seven patients, four patients had graft failure (57.14%), one was associated with rejection (Chr. ACR), one had associated CNI toxicity, and other two patients had HCV infection. The predominant native kidney disease was chronic kidney disease (CKD) of unknown etiology (57.14%), leading to end-stage renal disease, so we could not ascertain whether our cases were denovo or recurrent.[14]

CG after renal transplantation, as in native kidneys, has a uniformly poor prognosis. In their studies, Meehan et al. observed ESRD in 100% of the patients after an average of 9.8 months (range of 2–24 months).[13] Stokes et al. observed that 71% of the patients reached ESRD during the period of follow-up (2.6 months; range of 0–4 months).[11] Similarly, all patients with cFSGS progressed to graft loss within three years of diagnosis as compared with 40% graft loss in ncFSGS in Swaminathan et al.'s series.[12] Kanodia et al. reported 11 (52.38%) out of 21 patients in IKDRC study developed graft failure over a period of 2.2 ± 1.7 years.[14] Similarly in our study, graft failure was 57.14% [Figure 4]. There is no recommendation for therapy in allograft CG, but plasmapheresis and high-dose steroids were tried, especially when CG was associated with rejection.[17]

- Trend of Serum creatinine among patients

Conclusions

CG manifests usually with graft dysfunction and proteinuria. Graft failure occurred in more than half of affected individuals. Even though prevalence of CG is less in renal transplant recipients, it is an important entity because risk of graft loss is very high.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nephrotic syndrome, progressive irreversible renal failure, and glomerular “collapse”: A new clinicopathologic entity? Am J Kidney Dis. 1986;7:20-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with rapid decline in renal function (“malignant FSGS”) Clin Nephrol. 1978;10:51-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associated focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:669-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV-associated nephropathy. A unique combined glomerular, tubular, and interstitial lesion. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:87-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy: A clinically and pathologically distinct variant of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1994;45:1416-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Idiopathic collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: A clinicopathologic study. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1734-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy—Recurrence in a renal allograft. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:503-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy in renal transplant patients: Recurrence and de novo occurence. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;17:1331.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy in renal allograft biopsies: A study of nine cases. Indian J Nephrol. 2011;21:10-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy in renal allografts: A morphological pattern with diverse clinicopathologic associations. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:658-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing and noncollapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in kidney transplants. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2607-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- De novo collapsing glomerulopathy in renal allografts. Transplantation. 1998;65:1192-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Angiotensin antibodies and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:971-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zonal distribution of glomerular collapse in renal allografts: Possible role of vascular changes. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:437-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy in transplanted kidneys: Only a tip of the iceberg? J Transplant Technol Res. 2011;1:105e.

- [Google Scholar]