Translate this page into:

A 10-year Study: Renal Outcomes in Patients with Accelerated Hypertension and Renal Dysfunction

Previous Affiliation of Dr. Aleya Anitha: Department of Nephrology, Manipal Hospital, Old HAL Airport Road, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Hypertension is prevalent in 35%–46% of the general population; 1% of them experience accelerated hypertension. Among patients with accelerated hypertension, acute worsening of renal functions occur in 22%-55%. Morbidity and mortality rates are high. Partial renal recovery is seen in some, while others rapidly progress to end-stage renal disease.

Methods:

Patients who presented with accelerated hypertension, renal dysfunction, and had undergone renal biopsy were evaluated and their clinical profile was analyzed. Those who became dialysis dependent were excluded from further follow-up. Study outcome were blood pressure control, renal functions, requirement of renal replacement and mortality.

Results:

Of the 30 patients evaluated, age at presentation was 41.2 ± 15.46 years and 26 (86.7%) were males, 10 (33%) had presented with nonspecific complaints. Mean duration of hypertension and blood pressure were 21.93 months and 196 ± 20.8/129 ± 12.4 mmHg, respectively. Glomerulonephritis and hypertensive nephrosclerosis had similar characteristics except proteinuria (P = 0.04). Average follow-up (n = 25) duration was 3.69 years (range: 0.05–9.6). At the end of study, 6 were dialysis dependent, while in others, mean e-GFR was 23.96 ml/min/1.73 m2. Poor renal prognosis was predicted by glomerulonephritis (relative risk-4.6) and degree of interstitial fibrosis. Five-year patient and renal survival were 94.4% and 71.9%, respectively.

Conclusion:

Accelerated hypertension occurs among patients with both primary and secondary hypertension. It leaves permanent renal sequelae. Though some patients recover renal function partially, further progression is rapid, especially among those with chronic glomerulonephritis.

Keywords

Accelerated hypertension

chronic glomerulonephritis

hypertensive nephrosclerosis

renal and patient survival

reversible renal dysfunctions

Introduction

Hypertension is prevalent in 35%–46% of world's population older than 25 years of age.[1] Accelerated hypertension (AH) occurs in 1%–2% of all hypertensives.[2] Age at presentation is wide.[34] Pre-existing hypertension is absent in 36%.[3] Accelerated phase occurs even among treated patients.[5] Men are commonly involved (M:F = 2:1 to 8:1).[67] Rapid increase in blood pressure (BP) sets a vicious cycle consisting of blood-vessel wall stretch, activation of renin-angiotensin system, endothelial dysfunction and/or damage, and microthrombi formation.[8] End-organs like brain, heart, and kidneys may be irreversibly damaged.[2]

Among patients who present with AH, chronic kidney disease (CKD) is seen in 8.4%–31%; acute worsening of renal functions is in 22%–55%.[34] During acute phase, 6.6%–13% require dialysis.[39] The severity of renal impairment determines prognosis.[310] Death was attributed to uremia in 50%–60%, in one early series[11]; Lip et al. found it to be 40%.[12] Renal failure-related morbidity and mortality declined with the availability of dialysis.[11] Cerebrovascular accident (44%) and cardiovascular events (36%) complicate hypertensive crisis.[13] Other organ involvement also contributes to mortality. Lip et al. found that stroke, myocardial infarction, and heart failure caused 24%, 11%, and 10% of deaths, respectively.[12]

Malignant hypertension (MH) was associated with poor prognosis; some studies have analyzed autopsy samples for histology.[314] Mortality rates have improved to 15% among patients with MH; 3.9% among patients with AH due to primary hypertension.[39] In past, 5 yrs renal and patient survival were 50% and 75%, respectively, however, with the availability of calcium-channel blockers and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors it was 81% and 90%, respectively.[3] Literature analyzing patients with MH is flawed by different criteria used to diagnose MH and non-availability of histology in some studies. Harrington et al. studied 82 patients with MH, diagnosed by the presence of papilledema, after ganglion blocking agents were introduced. They found similar survival rates among patients with essential and renal hypertension during 7 years of follow-up; histology (autopsy) was available in 42 cases.[14] Our study fills the lacunae of a histology proven, long-term outcome study.

Methods

This study was done in a tertiary care center at Bangalore, in the southern part of India. All consecutive patients who were admitted to Nephrology wards with AH and renal dysfunction and had undergone renal biopsy were studied. Patients who could not undergo kidney biopsy due to small kidneys or those who refused consent for biopsy were excluded. Also, children (≤18 years) and pregnant women, patients with renovascular or urological disease, and those with scarred kidneys on ultrasound were excluded. A total of 30 patients were studied between February 2009 and February 2011 and follow up was available until Jun 2019.

AH included both hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. Hypertensive emergency and urgency were defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) above 179 and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) above 109 mmHg with or without target organ failure, respectively. Hypertensive encephalopathy, intracranial hemorrhage, unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction, acute left ventricular failure with pulmonary edema, dissecting aortic aneurysm, and acute renal failure were considered as target organ failures.[15] Renal dysfunction was defined as any estimated glomerular filtration rate (e-GFR) of less-than 90 ml/min.

All patients were evaluated with a detailed history, physical examination, retinal examination by ophthalmologist, laboratory investigation, echocardiogram, ultrasonography of abdomen, and renal biopsy. BP was recorded by qualified nurses and doctors using a mercury sphygmomanometer (Diamond). Serum creatinine was measured by Jaffe's kinetic method and e-GFR was calculated by CKD-EPI formula, online calculator https://qxmd.com/calculate/calculator_251/egfr-using-ckd-epi. Renal biopsy samples were obtained using disposable automatic biopsy gun (18-gauge needles; cutting length 22 mm) under USG guidance and local anesthesia. All slides were reported by qualified nephro-pathologists. Malignant hypertensive nephrosclerosis (MHN) and benign hypertensive nephrosclerosis (BHN) was defined on standard criteria.[16] CKD was classified as described by the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) guidelines.[17] All patients were followed up periodically by Nephrologists, for changes in BP and renal function; their antihypertensive drugs were modified as required. Renal replacement therapy was advised on standard criteria. Follow-up data was collected for the visits at 3rd, 6th months and then 1st, 2nd, 3rd years, and at the last visit. Statistical analysis was done using MS office excel 2007 version, averages were calculated with one standard deviation, significance was calculated with P value using 2 tailed student t-test. Survival analysis was done by Kaplan–Meier method using SPSS.

Results

Thirty patients who met the inclusion criteria were studied; 26 were males. Average age was 41.2 ± 15.46 years [Table 1]. Eleven patients were less than 30 years of age. Mean duration of hypertension was 21.93 months; 2 were diagnosed to have hypertension at presentation. Mean SBP and DBP were 196 ± 20.8 and 129 ± 12.4 mmHg respectively. Clinical presentation was breathlessness and edema (4), blurring of vision, headache, or seizures (8), and pedal edema (8). AH was detected incidentally among 10 patients when they had visited with nonspecific complaints. Seven (23%) had grade-IV hypertensive retinopathy. All patients had renal dysfunction as per inclusion criteria. Mean e-GFR was 25.3 ± 14.47 ml/min/1.73 m2; average urine PCR was 3.2 ± 2.86 g/g. Among all (n = 30), there was no pre-enrolment renal function evaluation in 17 patients; renal dysfunction was detected within the previous 1–8 weeks in 7. Six out of 30 patients had preexisting CKD; their average e-GFR at presentation was 16.85 ml/min/1.73 m2, while others (n = 24) presented with e-GFR of 27.41 ml/min/1.73 m2. Two (6.67%) needed dialysis on admission.

| Variables | All patients | HN vs CGN | MHN vs BHN | IgAN vs Other GN | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (%) | 30 | HN | 14 (46.7) | MHN | 9 (64.29) | IgAN | 9 (56.25) |

| CGN | 16 (53.3) | BHN | 5 (35.71) | Other GN | 7 (43.75) | ||

| Age (years) | 41.2 | HN | 42.57 | MHN | 44.1 | IgAN | 33.56 |

| CGN | 40 | BHN | 39.8 | Other GN | 48.29 | ||

| P=0.66 | P=0.57 | P=0.1 | |||||

| Male : Female | 26 : 4 | HN | 14 : 0 | MHN | 9 : 0 | IgAN | 6 : 3 |

| CGN | 12 : 4 | BHN | 5 : 0 | Other GN | 6 : 1 | ||

| Hypertension and proteinuria | |||||||

| Mean duration months (range) | 21.93 | HN | 35.64 | MHN | 51.75 | IgAN | 1.68 |

| CGN | 9.95 | BHN | 6.63 | Other GN | 20.57 | ||

| P=0.1 | P=0.18 | P=0.0056 | |||||

| Average SBP (range) mmHg | 196 | HN | 191.43 | MHN | 192.22 | IgAN | 204.44 |

| CGN | 200 | BHN | 190 | Other GN | 194.29 | ||

| P=0.27 | P=0.86 | P=0.34 | |||||

| Average DBP (range) mmHg | 129 | HN | 129.29 | MHN | 126.67 | IgAN | 131.11 |

| CGN | 128.75 | BHN | 134 | Other GN | 125.71 | ||

| P=0.91 | P=0.29 | P=0.43 | |||||

| PCR (range) g/g | 3.2 | HN | 2.05 | MHN | 2.66 | IgAN | 3.71 |

| CGN | 4.2 | BHN | 0.96 | Other GN | 4.83 | ||

| P=0.04 | P=0.28 | P=0.43 | |||||

| Renal dysfunction (n=30) | |||||||

| Mean duration (range) months | 2.62 | HN | 2.2 | MHN | 3.08 | IgAN | 0.08 |

| CGN | 2.98 | BHN | 0.6 | Other GN | 6.71 | ||

| P=0.72 | P=0.5 | P=0.02 | |||||

| Mean e-GFR (range) ml/min/1.73 m2 (EPI) | 25.3 | HN | 22.17 | MHN | 20.31 | IgAN | 29.53 |

| CGN | 28.04 | BHN | 25.52 | Other GN | 26.11 | ||

| P=0.28 | P=0.37 | P=0.71 | |||||

BHN – Benign Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis; CGN – Chronic Glomerulonephritis; HN – Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis; IgAN – IgA Nephropathy; MHN – Malignant Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis; Other GN – Other Glomerulonephritis

Histology revealed hypertensive nephrosclerosis (HN) and chronic glomerulonephritis (CGN) among 14 and 16 patients, respectively [Table 2]. Tubular atrophy was ≤25% in 15. The severity of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) was similar among HN and CGN. Baseline clinical characteristics were statistically similar between HN and CGN; except that proteinuria was lower among those with HN (P = 0.04) [Table 1]. Three out of 14 (21.4%) with HN were aged ≤30 years; however, those aged ≤30 years were likely to have CGN (RR = 1.3). IgAN was the commonest CGN. Mean duration of hypertension was lesser (P < 0.01) among those with IgAN (1.68 months) as compared to other GNs (20.57 months). Proteinuria was similar (P = 0.43) [Table 1]. Patients with IgAN (44%) and MHN (44%) were likely to present with symptoms of hypertensive retinopathy.

| HN and CGN | Other histological findings |

|---|---|

| HN (n=14) | Severe arteriolar lesions (n=29) |

| MHN (n=9) | Onion skin appearance (6) |

| Proliferative endarteritis (6) | TMA (7) |

| Fibrinoid necrosis (1) | Fibrinoid necrosis (1) |

| TMA (6) | HN histology was seen in those with CGN (n=6) |

| BHN (n=5) | Wrinkling of basement membrane (1) |

| Wrinkling of basement membrane (4) | Hyaline arteriosclerosis (5) |

| Hyaline arteriosclerosis (2) | TMA (1 in association with MPGN) |

| Intimal thickening (2) | IFTA (n=30) |

| CGN (n=16) | ≤ 25% (15) |

| IgAN (9) | > 25% ≤ 50% (11) |

| Diabetic nephropathy (1) | > 50% (4) |

| FSGS (3)* | ATN was seen in 2 |

| MPGN pattern (3) | CIN was seen in 2 |

ATN–Acute Tubular Necrosis; BHN–Benign Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis; CGN– Chronic Glomerulonephritis; CIN–Chronic Interstitial Nephritis; FSGS–Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis; HN–Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis; IFTA–Interstitial Fibrosis and Tubular Atrophy; IgAN–IgA Nephropathy; MHN–Malignant Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis; MPGN–Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis; Other GN– Other Glomerulonephritis; TMA–Thrombotic Microangiopathy. *All patients with FSGS were considered to be primary, short of electron microscopy, with clinical and histological features

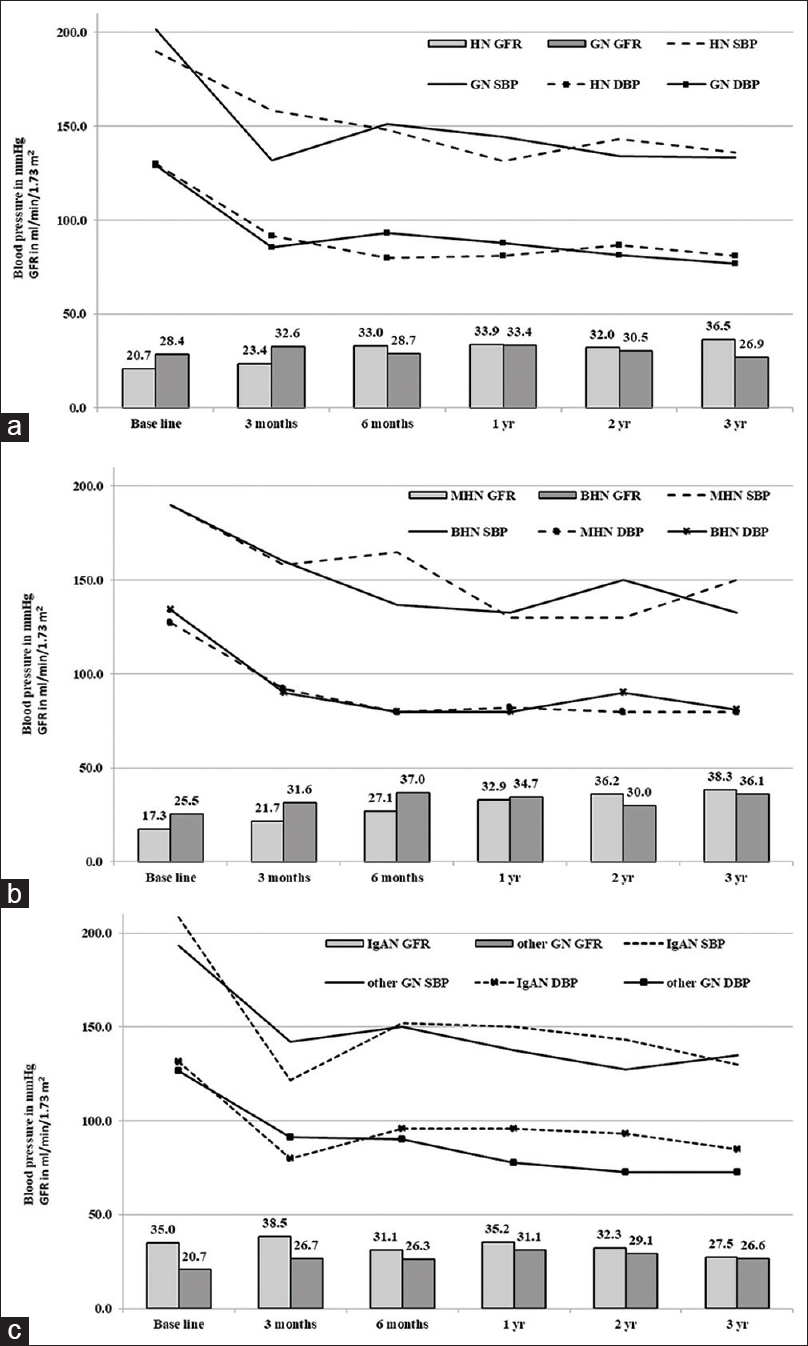

Twenty-five patients were followed up after excluding 5 (dialysis dependent at presentation-1; no visits-4). BP was comparable among those with HN and CGN, MHN and BHN, and IgAN and other GN [Figure 1]. Average e-GFR improved from 24.73 ± 13.53 ml/min/1.73 m2 to 33.6 ± 11.88 ml/min/1.73 m2 over the first year (P = 0.06) and remained stable later Figure 1. The improvement in e-GFR was statistically similar among all subgroups [Figure 2].

- Blood pressures and e-GFR of all followed-up patients (n = 25) during the study period

- Comparison of blood pressures and e-GFR during the study period (a) Hypertensive nephrosclerosis (HN) versus glomerulonephritis (GN), (b) Malignant hypertensive nephrosclerosis (MHN) versus benign hypertensive nephrosclerosis (BHN), (c) IgA nephropathy (IgAN) versus other glomerulonephritis (other GN)

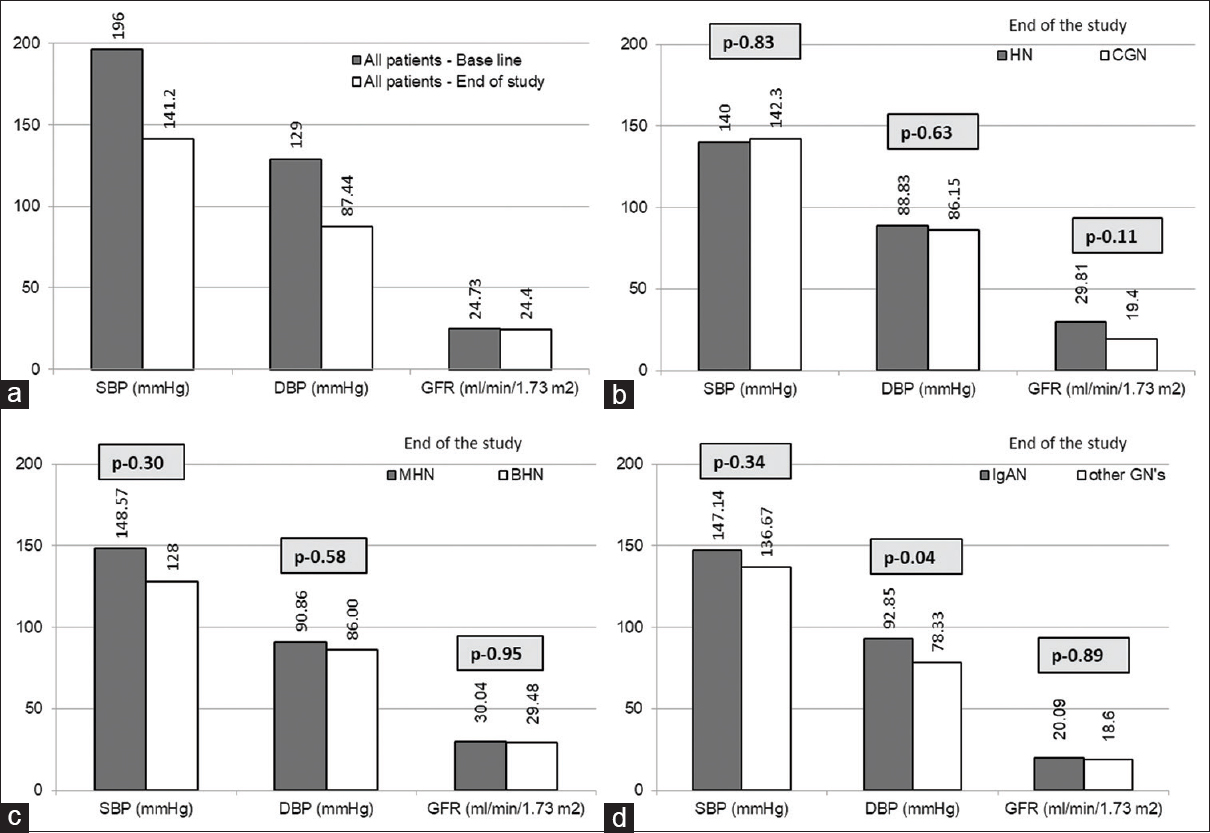

The average follow-up period was 3.69 years (n = 25). The mean BP at the end of the study was 140/86 mmHg. BP was statistically similar among the subgroups [Figure 2]. e-GFR change among those with CGN (7.91 ml/min/1.73 m2/year loss) and HN (0.54 ml/min/1.73 m2/year gain) was not statistically different (P = 0.24). The difference in the e-GFR between BHN vs MHN (P = 0.61) and IgAN vs other GNs (P = 0.12) at the end of the study were statistically similar [Figure 3]. e-GFR among those who were not permanently dialysis-dependent (n = 19) was 29.49 ml/min/1.73 m2 with an improvement of 1.54 ml/min/1.73 m2/year. However, they remained with CKD stages III (9), IV (5), and V not on dialysis (5).

- Comparison of blood pressures and e-GFR (a) Base line versus end of the study values of all follow-up patients (n = 25), (b) Hypertensive nephrosclerosis (HN) versus glomerulonephritis (GN) at the end of study, (c) Malignant hypertensive nephrosclerosis (MHN) versus benign hypertensive nephrosclerosis (BHN) at the end of study, (d) IgA nephropathy (IgAN) versus other glomerulonephritis (other GN) at the end of study

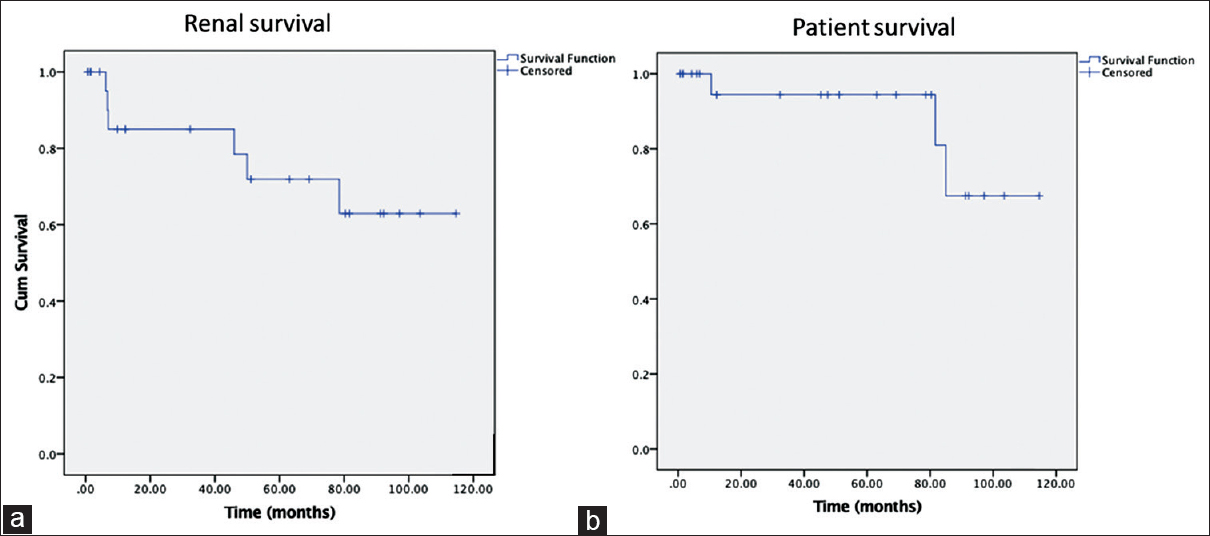

Six patients on follow-up became dialysis dependent during the study period; their e-GFR had dropped by 20.94 ml/min/1.73 m2/year. There was a bimodal distribution; 3 patients required dialysis within 7 months, while another 3 after 46 months. Mean duration to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) was 32.51 months. One additional patient with MHN required dialysis for 7 weeks until he recovered renal functions. Factors predicting progression to ESRD were CGN as compared to HN (RR = 4.6), and IFTA >25% as compared to IFTA ≤25% (RR = 4.6). Renal survival was 85% at 1 year and 71.9% at 5 years. Mortality occurred in 3 (10%); cause of death was vascular events in 2 and unrelated in the other. Patient survival was 94.4% at 5 years [Figure 4].

- Kaplan Meier survival curves - a) renal survival, b) patient survival

Discussion

This study highlighted that HN can occur at younger age. BHN is not benign. Recovery of renal functions after an episode of AH is partial, both among those with HN and CGN. AH occurs in 1%–2% of all adult hypertensives with male predominance.[267] Time from the detection of hypertension to accelerated phase is variable; we found the range to be 0–180 months.[6] Age of onset for primary and secondary hypertension (Sec.HT) are different, though the spectra overlap. We found that both groups presented with AH, at a similar age (P = 0.66); however, ranges were wide. Younger age (≤30 years) were more likely to have Sec.HT (RR = 1.3). AH commonly presents with neuro-retinopathy or volume overload. Some patients remain asymptomatic, despite the presence of end-organ involvement, while others present with nonspecific symptoms.[518] Ten out of our 30 patients had presented with nonspecific symptoms. Patel et al. reported 4.6% of all out-patients visiting multispecialty health care system to have asymptomatic severe hypertension (≥180/110 mmHg).[19]

Papilloedema, diagnostic of MH, is a subjective finding, with discordance even among experts; its presence is inconsistent.[20] Degree of hypertensive retinopathy does not linearly correlate with severity of renal dysfunction or progression to ESRD.[21] Our results concurred with these findings.

While both essential and Sec.HT lead to AH, their individual proportions in any given study population depend on the selection criteria. Clinical parameters cannot differentiate them. We found that severity of hypertension (P = 0.27) and renal dysfunction (P = 0.28) at presentation were similar between the two groups. Proteinuria was higher among CGN (P = 0.04); however, the ranges were wide. Common secondary causes are renal parenchymal and renovascular; we found Sec.HT in 53.3% even after excluding renovascular diseases and scarred kidneys. Often when renal biopsy is deferred among patients with bland sediments, serum creatinine <2 mg/dL, and slowly progressing renal dysfunction, presuming it to be HN; CGN can be missed. When lesions of HN and CGN co-exist in the same biopsy, it is difficult to distinguish as to which one of them was primary or attribute their individual contribution to chronicity.[16]

Lesions of HN are considered to occur in patients with long-standing hypertension and, hence, in older age group.[16] Episodes of AH can silently overwhelm autoregulatory protective vasoconstriction, at any time after detection of hypertension.[19] Wide and rapid fluctuations in BP leads to end-organ damage.[13] We found 3 out of 14 (21.4%) were younger than 30 years of age; 7 (50%) were known to be hypertensive for ≤6 months and 10 were on antihypertensive medications. Average age at presentation was similar between those who had MHN and BHN. Dichotomy of hypertension and normotension fails to recognize the risk of end-organ damage which are directly related to increasing levels of BP even within the conventional normal levels.[22]

BHN is a misnomer. HN, in both its benign and malignant forms, can cause renal dysfunction[23] More than 50% of patients with BHN progress to ESRD in 10 years; it was 80% by 20 years.[24] At the end of study period, we found e-GFR of patients with MHN (30.04 ml/min/1.73 m2) and BHN (27.32 ml/min/1.73 m2) were similar (P = 0.75). Rate of e-GFR drop among BHN (n = 5) was 3.33 ml/min/1.73 m2/year; none required dialysis over 66.4 months.

During an episode of AH, precipitous drop in e-GFR is attributed to microangiopathic hemolysis, loss of auto regulation, and ischemia. Overenthusiastic and rapid correction of BP enhances the risk of poor perfusion. Renal functions improve with time or remain stable following an episode of AH.[3] Some of them especially MHN with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia can attain dialysis independence over time.[2526] Among those who did not require dialysis during the study period, there was 1.54 ml/min/1.73 m2/year gain in e-GFR; this average was contributed by those with HN especially MHN. One patient with MHN, who required dialysis at presentation recovered renal functions at the end of 7 weeks.

Renal functions and proteinuria at presentation and poor BP control during follow-up are risk factors predicting progression of CKD.[3] On comparing those who became dialysis dependent during the study period versus those who did not, we found at presentation, their e-GFR (P = 0.22) and proteinuria (P = 0.9) were similar; however, the ranges were wide. BP was higher (P < 0.05) among those who became dialysis dependent at 6th month follow-up; however, such differences in BPs were not noted on further follow-up. Secondary etiology for AH is another risk factor for CKD progression.[3] At the end of study period, CGN and HN had statistically similar SBP (P = 0.77), DBP (P = 0.86), and renal functions (P = 0.15); however, those with CGN were likely to become dialysis dependent (RR = 4.6). Those with IgAN, the commonest CGN, were more likely to progress to ESRD as compared to other GNs (RR = 2.6). IFTA is a predictor of progression. We found even IFTA of >25% to ≤50% was associated with increased risk of progression to ESRD as compared to those with IFTA of ≤25% (RR-5.3).

Among patients presenting with AH, efficient antihypertensive medications, sustainable dialysis, and renal transplant have prolonged survival. Mortality and 5-year patient survival were 55%–75% and 63%–75% among earlier studies.[679101227] Roberto et al. in their cohort of patients with AH, in whom secondary causes were excluded, reported a mortality rate of 3.9%, and 5-year patient and renal survival were 96% and 84%, respectively. In our study, which included AH due to both primary and secondary etiology, mortality rate was 10%; 5-year patient and renal survival were 94.4% and 71.9%, respectively.

Strength of this study was availability of histological diagnosis, long-term follow-up, and analysis of renal and patient survival. Our study was limited by the small cohort size and lack of analysis of proteinuria during follow-up. Parallel analysis of patients admitted during the same time period with AH and renal dysfunction but not biopsied would have enhanced the impact of this study.

Conclusion

AH continues to occur and is associated with irreversible end-organ damage. One-fourth of the patients become dialysis dependent with rapid loss of e-GFR. Renal recovery among others is only partial. All patients remained with CKD stage III or worse. CGN and higher degree of IFTA are risk factors for CKD progression. Patient and renal survival have improved with availability of renal replacement therapy and better antihypertensive medications.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 2013. A global brief on hypertension. Available from: http://wwwwhoint/cardiovascular_diseases/publications/global_brief_hypertension/en/

- Long-term renal survival in malignant hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3266-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Practice patterns, outcomes, and end-organ dysfunction for patients with acute severe hypertension: The Studying the Treatment of Acute hyperTension (STAT) Registry. Am Heart J. 2009;158:599-606.

- [Google Scholar]

- The failure of malignant hypertension to decline: A survey of 24 years' experience in multiracial population in England. J Hypertens. 1994;12:1297-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant hypertension (a clinico-pathologic study of 43 cases) J Postgrad Med. 1987;33:49-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving survival of malignant hypertension patients over 40 years. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:1199-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term renal outcome in patients with malignant hypertension: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant hypertension: Aetiology and outcome in 83 patients. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1986;8:1211-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Malignant hypertension and hypertensive emergencies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:133-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complications and survival of 315 patients with malignant-phase hypertension. J Hypertens. 1995;13:915-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypertensive crisis: Hypertensive emergencies and urgencies. Cardiol Clin. 2006;24:135-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Results of treatment in malignant hypertension: A seven-year experience in 94 cases. Br Med J. 1959;2:969-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal disease caused by hypertension. In: Charles J, Silva FG, Olson JL, D'Agati VD, eds. Heptinstall's Pathology of the Kidney (7th ed). 2015. p. :317-423.

- [Google Scholar]

- Definition and classification of chronic kidney disease: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Kidney Int. 2005;67:2089-100.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypertensive urgencies and emergencies.Prevalence and clinical presentation. Hypertension. 1996;27:144-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characteristics and outcomes of patients presenting with hypertensive urgency in the office setting. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:981-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- From malignant hypertension to hypertension-MOD: A modern definition for an old but still dangerous emergency. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30:463-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Progression of renal failure – The role of hypertension. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:8-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hypertensive nephrosclerosis as a relevant cause of chronic renal failure. Hypertension. 2001;38:171-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microangiopathic haemolysis and renal failure in malignant hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:246-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Partial recovery of renal function in black patients with apparent end-stage renal failure due to primary malignant hypertension. Nephron. 1995;71:29-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing mortality in malignant hypertension. J Hypertens Suppl. 1985;3:S405-7.

- [Google Scholar]