Translate this page into:

Daily Urinary Sodium Excretion Monitoring in Critical Care Setting: A Simple Method for an Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Making an early diagnosis of acute kidney injury (AKI) is crucial. Classical biomarkers are not capable of early detection of AKI, but novel biomarkers that do have this capability are expensive and not universally available. This prospective study attempts to mitigate these limitations through the evaluation of daily urine analysis on patient admitted to a critical care unit in order to detect early AKI.

Methods:

Daily urinary indices were measured on every patient admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) from the time of admission until his/her discharge from the ICU or death. This renal monitoring consisted of daily blood and spot morning urine samples in order to measure creatinine, urea, sodium, chloride and potassium in order to calculate the fractional excretion of sodium (FENa), chloride, urea and potassium. The data collected on these patients in the previous days was analyzed to determine whether or not there was a significant statistical difference in the urinary indices one day before the clinical diagnosis of AKI (day – 1) and 2 days before the diagnosis (day – 2). The statistical test applied was a single rank test, using as a limit of significance a value of P < 0.05.

Results:

Of the 203 patients included, 61 developed AKI. A statistical significant difference was documented only in the value of urinary sodium (UNa) and FENa between day-1 (one day before AKI clinical diagnosis) and day-2 (two days before AKI clinical diagnosis).

Conclusion:

Daily monitoring of UNa and FENa detected a significant change in their basal values 24 hours before clinical diagnosis of AKI was made.

Keywords

Acute kidney injury

critical care unit

diagnosis

renal monitoring

urinary indices

Introduction

An early diagnosis of acute kidney injury (AKI) is crucial in order to achieve its prompt management and optimize its evolution and prognosis. However, classical AKI biomarkers, such as serum urea and creatinine, achieve AKI diagnosis relatively late.[1] Because of this, the use of novel and earlier (subclinical) biomarkers have recently been proposed for this purpose.[234567891011] However, these novel biomarkers are not only expensive and unavailable in all healthcare centers, but they also do not guarantee the immediate detection of AKI since their request also depends on the clinical suspicion of the physician.[34567891011]

It is known that renal physiological changes usually precede renal parenchyma damage, and that this phenomenon can be detected by changes on the urinary indices.[1] It has already been documented that standard values of classical urinary indices, such as urinary sodium (UNa), fractional excretion of sodium (FENa), fractional excretion of urea (FEU), etc. were not absolutely reliable for distinguishing pre-renal AKI (functional) from renal AKI (structural). To our knowledge it has not yet been evaluated whether these urinary indices, independent of their absolute values, could detect subclinical AKI by showing an abrupt and significant change in their basal values when they have been monitored since the patient's admission. In this sense, urinary indices monitoring could be very useful on critical care patients in order to achieve an early diagnosis of AKI since these indices have a lower cost and higher availability compared to monitoring using novel AKI biomarkers (e.g.: neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, etc.), and is a preferable option over treating an AKI with a delayed diagnosis.[1111213] Therefore, we did this prospective study that evaluated whether daily monitoring of urinary indices in critical care patients, who were not suffering from AKI since their admission, could show a significant abrupt change in their values before the clinical appearance of AKI, resulting in an early (subclinical) AKI diagnosis [Table 1].

| Renal condition | Definition |

|---|---|

| Subclinical AKI | This diagnosis is based only on the increased levels of renal injury biomarkers before any clinical manifestation: serum creatinine elevation and/or oliguria. |

| AKI | The clinical manifestation of renal injury which lasts less than 7 days, and depending on its duration can be “transient” (≤48 h), or “persistent” (>48 h) |

| ARD | The clinical manifestation of renal injury which lasts between 7 to 90 days. |

| CKD | The renal injury which lasts more than day 90 from the acute event. |

AKI: Acute kidney injury, ARD: Acute renal disease, CKD: Chronic kidney disease

Methods

Daily measurement of urinary sodium (UNa), urinary chloride (UCl), fractional excretion of sodium (FENa), fractional excretion of chloride (FECl), fractional excretion of potassium (FEK), and fractional excretion of urea (FEU) was carried out on every patient in critical care unit, who was not suffering from AKI, since admission and until discharge or death.

The study was carried out for two months, and each patient's age, gender, cause of ICU admission, and administered drugs were documented, particularly diuretics, inotropic agents, corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB), intravenous contrast, and/or nephrotoxic antibiotics. The presence of these drugs was evaluated due to their potential influence on glomerular and tubular functions, and consequently on their urinary indices values. However, patients on these drugs were not excluded from the study because the objective was to evaluate the utility of urinary indices for renal monitoring in real clinical settings.

The only exclusion criteria was being a patient on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis on admission to the ICU.

AKI clinical diagnosis was based on KDIGO-2012 criteria:[14]

-

Serum creatinine increase >0.3 mg/dl or 1.5-1.9 times baseline value, and/or

-

Urinary output drop to 0.5 ml/kg/hour throughout 6 hours.

The day of the clinical diagnosis of AKI was considered “day zero “ [Figure 1]. Of the patients included in the study, those that did develop AKI had their previous urinalyses evaluated to see if there was a significant statistical contrast in the difference (delta value) between their urinary indices values one day before (day-1) and two days before clinical AKI diagnosis (day-2) [Figure 1].

- Difference between day -1 urinary index and day-2 urinary index (Delta urinary index)

The statistical test applied was a single rank test, taking as a limit of significance a value of P < 0.05.

The study was approved by the Institutional Bioethical Committee, and informed consent was obtained from all the participants included in the study.

Results

This prospective study included 61 patients who developed AKI after their admission to the ICU from a total number of 203 patients admitted during the study period. The median age was 60 years (range: 46-72), and 34 of them were male. In the study group, 66% were on inotropic drugs, 41% on furosemide, 37% on non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, 33% on ACEI/ARB, 26% on nephrotoxic antibiotics. However, none of them were on corticosteroids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories drugs (NSAID) or intravenous contrast at the time of AKI diagnosis. Regarding the etiology of AKI, the following causes were documented: postoperative (30%), cardiorenal syndrome (29%), sepsis (26%), systemic inflammatory response syndrome (9%), and hypovolemic shock (6%); although all these patients were at least on two potential nephrotoxic drugs, thus making AKI etiology multifactorial [Table 1].

None of these patients had a fatal outcome, dialysis requirement, non-resolving AKI before their discharge from ICU. It is worth mentioning that patients who received furosemide were on this drug before AKI diagnose and its prescribed dose was not changed in the period between day-2 day and day zero. In this study, a statistical significant variation was found in the difference (delta value) between serum urea and serum creatinine values of day 0 (the day of AKI clinical diagnosis) and day-1 (one day before AKI clinical diagnosis) [Table 2].

| DAY-2 X±SD | DAY-1 X±SD | DAY 0 X±SD | Delta A X±SD | Delta B X±SD | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sCr (mg/dl) | 0.7±0.2 | 0.7±0.3 | 1.4±0.5 | 0.9±0.3 | - | 0.003 |

| sU (mg/dl) | 38±10 | 39±15 | 53±22 | 14±6 | - | 0.01 |

| sNa (mmol/L) | 139±10 | 139±10 | - | 0 | - | NS |

| uCr (mg/dl) | 20.9±0.1 | 9.8±0.1 | - | -11±0.1 | - | 0.001 |

| uNa (mmol/L) | 74.8±48 | 87±41 | - | - | 38±57 | 0.001 |

| FENa (%) | 1.8±2.3 | 4.5±6.4 | - | - | 2.6±5.5 | 0.007 |

sU: Serum urea, sCr: Serum creatinine, sNa: Serum sodium, uCr: Urinary creatinine, uNa: Urinary sodium, FENa: Fractional excretion of sodium. Delta A: (day 0) - (day-1), Delta B: (day-1) - (day -2)

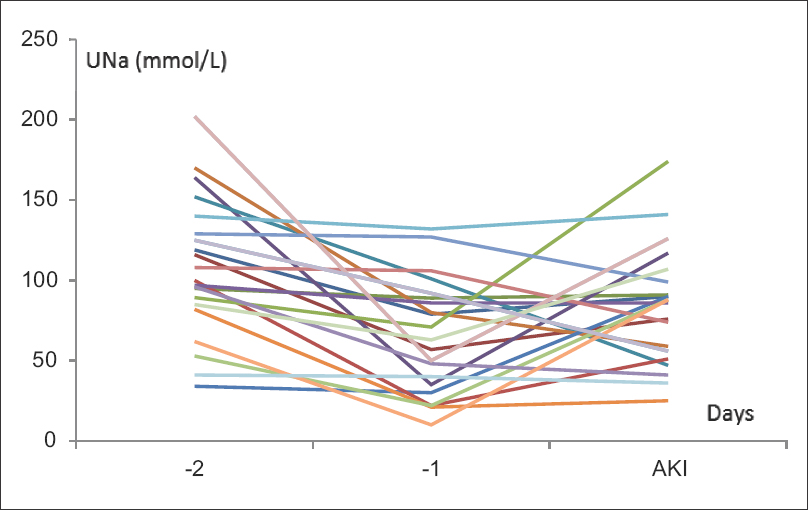

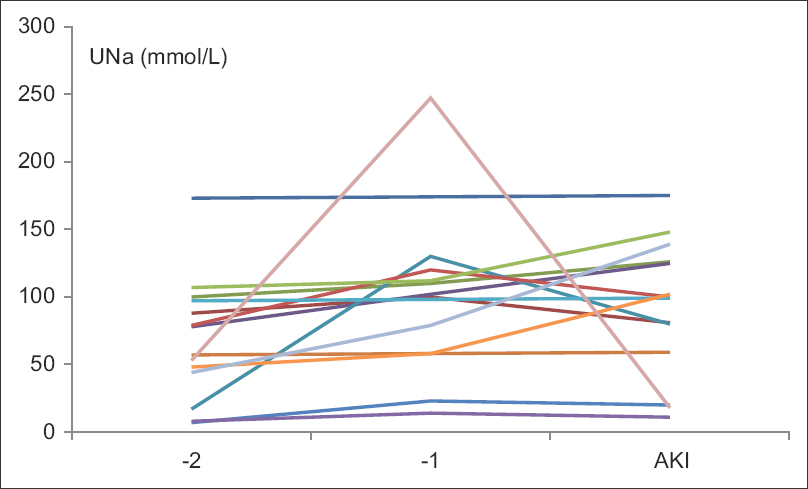

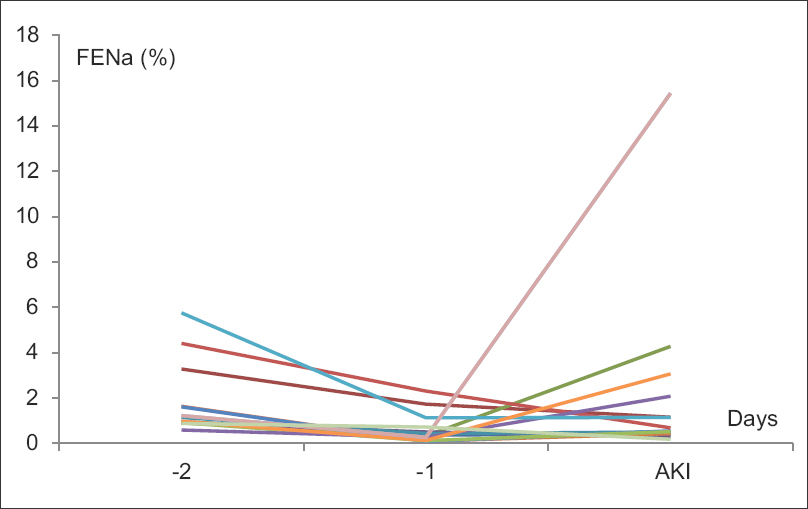

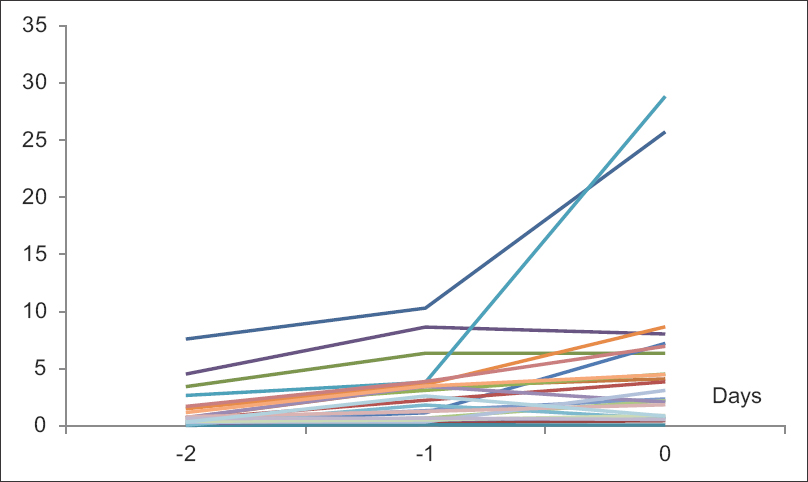

In addition, it was evaluated if there was a significant difference (positive or negative) in the value of the studied urinary indices (UNa, UCl, FENa, FECl, FEU, and FEK) and volume diuresis between day-1 and day-2, and it was found that there was only a statistical significant difference in UNa, and FENa values between these 2 days [Table 2 and Figures 2–5]. In addition, no urinary indices showed significant variation in non-AKI patients during their stay in ICU.

- Urinary sodium (UNa) descending values 24 hours before AKI diagnosis. AKI: Acute kidney injury

- Urinary sodium (UNa) ascending values 24 hours before AKI diagnosis. AKI: Acute kidney injury

- Fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) descending values 24 hours before AKI diagnosis. AKI: Acute kidney injury

- Fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) ascending values 24 hours before AKI diagnosis. AKI: Acute kidney injury

Discussion

Since vital organs must be continuously monitored in ICU patients, continuous electrocardiograms and oxygen saturation monitoring are always performed on critical care patients in order to have an early detection of cardiac or respiratory dysfunction, respectively. However, renal monitoring is usually performed by measuring daily serum urea and creatinine despite they are late AKI markers.[115] Because of that, novel biomarkers such as N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase, interleukin-18, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, midkine, microRNAs, kidney injury molecule, L-type fatty acid-binding protein, etc. have been proposed for achieving an early AKI diagnoses.[23456789101116] However, novel biomarkers are expensive, not universally available in medical centers, and they do not imply an immediate AKI detection, since their request still depends on the suspicion of kidney injury by the physician.[34567891011121314] Therefore, there is not yet an effective tool for achieving an early and simple AKI diagnosis in ICU patients. Thus, this study evaluated whether daily measurement of urinary indices (UNa, UCl, FENa, FECl, FEK, FEU) in every critical care patient that was not suffering from AKI, since his/her admission and until his/her discharge or death, could be useful for a subclinical and affordable AKI detection.[1314]

It is worth pointing out that patients suffering from chronic kidney disease (CKD), and patients on drugs which could modify their urinary indices values were not excluded from the study on purpose, due to the following reasons:

-

CKD and potential nephrotoxic drugs are frequently documented in critical care patients, and the objective of this study was to evaluate weather daily renal monitoring of urinary indices could achieve an early AKI detection in a real clinical setting

-

AKI diagnosis should not be based on absolute urinary indices values (as it was Miller et al.'s classical proposal) but on relative and significant change (increase or decrease) in urinary indices with respect to their basal value.

In this study, it was shown that UNa and FENa were the only studied urinary indices which showed a statistical significant change in its day -1 value compared to its day-2 value, which means that these indices changed before AKI clinical diagnosis. AKI diagnosis was determined by a significant increase in serum creatinine value or reduction in urinary volume based on KDIGO-2012 AKI definition [Tables 1, 2 and Figures 2–5].

This preceding change in UNa and FENa could be explained by the fact that any AKI inducing agent (ischemic or toxic) can alter renal perfusion or sodium pump and/or transporter function (sodium loss) at any nephronal segment, leading to a significant change in urinary sodium excretion, independent of the basal urinary sodium value. It is worth mentioning that variation in dosage of diuretics were not the reason for the above mentioned urinary indices changes since the studied patients who were on diuretics were on them for many days before the evaluated days (days -2, -1 and 0), and there was no change in the prescribed dosage of the diuretics during these days.

Since it was documented that UNa and FENa values significantly changed 24 hours before clinical AKI diagnosis, and these urinary indices are relatively inexpensive and universally available, their daily monitoring in critical care patients who were not suffering from AKI, could be used for monitoring renal function in order to achieve early detection of AKI in this population.

Conclusion

In this study, it was documented that daily monitoring of urinary sodium and fractional excretion of sodium detected a significant change in the basal values of these urinary indices 24 hours before clinical diagnosis of acute kidney injury in critical care unit patients.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants included in the study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Renal Pathophysiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1994. p. :267-90.

- Novel acute kidney injury biomarkers: Their characteristics, utility and concerns. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018;50:705-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary biomarkers at the time of AKI diagnosis as predictors of progression of AKI among patients with acute cardiorenal syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1536-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of urinary midkine as a biomarker in patients with acute kidney injury. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21:597-607.

- [Google Scholar]

- Circulating MicroRNA-188, -30a, and -30e as early biomarkers for contrast-induced acute kidney injury. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5 pii: e004138. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004138

- [Google Scholar]

- Biomarkers in acute kidney injury-pathophysiological basis and clinical performance. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2017;219:554-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early detection of acute kidney injury after pediatric cardiac surgery. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;41:9-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of serum creatinine, cystatin C, and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for acute kidney injury occurrence according to risk, injury, failure, loss, and end-stage criteria classification system in early after living kidney donation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2016;27:659-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictive ability of urinary biomarkers for outcome in children with acute kidney injury. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:521-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of three early biomarkers for acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery under cardiopulmonary bypass. J Intensive Care. 2016;4:41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Urinary indices: Their diagnostic value in current nephrology. Front Med Health Re. 2017;1:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Looking for a better definition and diagnostic strategy for acute kidney injury: A new proposal. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2019;117:4-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1-38.

- Evaluation of osmolar diuresis as a strategy to increase diagnostic sensitivity in acute kidney injury. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2019;117:e202-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute kidney injury pharmacokinetic changes and its impact on drug prescription. Healthcare (Basel). 2019;7:10.

- [Google Scholar]