Translate this page into:

Renal Lymphoma Diagnosed on Kidney Biopsy Presenting as Acute Kidney Injury

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Renal manifestations associated with hematolymphoid malignancies are known. Primary or secondary involvement of the kidney by lymphomatous infiltration has various clinical presentations. Acute kidney injury is not an uncommon finding in relation to lymphomatous interstitial infiltration proven on kidney biopsy. However, diagnosing it solely on renal biopsy remains a challenge and needs expertise and aid of immunohistochemistry as the prognosis is dismal.

Methods:

This is a retrospective study of kidney biopsy-proven cases of renal lymphoma presenting with acute kidney injury.

Results:

The study included 12 patients with ages ranging from 4 to 50 years who presented with serum creatinine ranging 2.1–9.6 mg%. Renal biopsy findings showed interstitial lymphomatous infiltrate. Two cases were diagnosed as primary lymphoma and the other 10 as secondary lymphomas. Among the 12 cases, nine were B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, of which diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was diagnosed in six (50%), low-grade B-cell type in two (16.6%), chronic lymphocytic leukemia in one (8.3%), and three were T-cell-type. Two were acute T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma and one other was a high-grade T-cell lymphoma. Four patients succumbed. The other four patients are alive; one is on chemotherapy, while two of them are on hemodialysis.

Conclusion:

Acute kidney injury as a presenting feature with lymphomatous infiltration of renal parenchyma is not uncommon. The patchy involvement makes it challenging on kidney biopsy with definitive diagnosis being made with the help of immunohistochemistry. Appropriate multidisciplinary involvement improves patient outcome.

Keywords

Acute kidney injury

lymphomatous infiltrate

renal lymphoma

Introduction

Renal manifestations in hematolymphoid neoplasms are known to involve few or all the compartments of the kidney, that is, glomerulus, tubules, interstitium, and vessels. Renal disease prevalence in patients with hematologic malignancies is variable, ranging from 7% to 34%.[1] Depending on the involvement pattern, the clinical manifestations vary from paraneoplastic glomerulopathies to interstitial lymphomatous infiltration where they present with acute renal dysfunction, which requires immediate diagnosis and treatment.[1] Acute kidney injury (AKI) due to lymphomatous infiltration of the kidney is seen in approximately 1%.[2] Renal involvement as a part of systemic lymphoma has been mentioned in the literature in one of the autopsy studies with a prevalence of up to 60%–90%.[123] Primary lymphomas of the kidney are rare, accounting for approximately 1%.[4] In the literature, many single case reports of renal lymphomas presenting with kidney injury are documented, whereas very few case series are available. However, diagnosing it solely on renal biopsy remains a challenge and needs expertise and aid of immunohistochemistry (IHC) as the prognosis is dismal.

Materials and Methods

The present study was carried out as a retrospective observational study of all patients with lymphoproliferative disorders, both primary and secondary lymphoma, diagnosed on kidney biopsy, presenting as acute kidney injury at the Department of Histopathology, Apollo Hospital, Jubilee Hills, Hyderabad between January 1, 1991 and July 31, 2013.

Patient selection

All the renal biopsies received in the laboratory were processed and analyzed in the Department of Histopathology, Apollo Hospital, Jubilee Hills, Hyderabad, India.

Clinical parameters

The clinical information was collected from the electronic database of Apollo hospital, and request forms were used for referral for samples received from other hospitals.

The data included age, sex, lymphoma type, presenting symptoms, and presence of lymphadenopathy or organomegaly. Biochemical data included serum creatinine.

Histological examination

The renal biopsies were processed according to the standard protocols for light microscopy. Hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid Schiff (PAS), Masson's trichrome, and periodic acid silver methenamine stains were done, and immunofluorescence study (IF) was done using antibodies to IgG, IgA, IgM, C3c, C1q, kappa, and lambda. Immunophenotyping of the lymphomas was performed on deparaffinized sections by using the immunoperoxidase and avidin-biotin techniques. The phenotype of the cellular infiltrate was studied using IHC stains with biotinylated CD 3, CD20, and TdT.

Follow-up data were collected from the treating clinicians.

Results

Our study included 12 cases who presented with acute kidney injury where renal biopsies were performed and histology showed interstitial lymphomatous infiltration.

Clinical and biochemical findings

The patient age range varied from 4 years to 50 years with a mean age of 31.5 years. The male to female ratio was 11:1 with a male predominance.

All the patients presented with features of acute kidney injury with serum creatinine ranging 2.1–9.6 mg/dl, with varying signs and symptoms.

Out of the 12 patients, rapidly progressive renal dysfunction was noted in cases 10 and 11, one other patient (case 8) presented with acute uric acid nephropathy and oliguria, and case 9 presented with pain in the small joints. [Table 1].

| Case number | Age in (years)/Sex | Clinical presentation | Serum. Creatinine (mg/dl) | IHC | Diagnosis NHL | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6/M | ARF as initial presentation, Hepatic SOL, Fever, Anemia | 1.9 | CD20+, CD3- | High-grade B-cell lymphoma | Patient died after 3 weeks of diagnosis |

| 2 | 47/M | History of NHL since three years, now ARF | 4 | CD20+, CD3- | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | LTFU |

| 3 | 50/M | History of Thymoma, post CT and RT, now abdominal pain | 5.6 | CD20-, CD3+ | High Grade T-cell lymphoma | LTFU |

| 4 | 45/M | ARF primary presentation, Abdominal lymph nodes, | 4.6 | CD20+, CD3- | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Patient died within one month of diagnosis (CNS Bleed |

| 5 | 25/M | Unexplained ARF | 3.5 | CD20+, CD3- | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | LTFU |

| 6 | 46/F | History of NHL, 6 cycles of chemotherapy, now ARF | 3.2 | CD20+, CD3- | B-cell lymphoma | LTFU |

| 7 | 28/M | Rapidly progressing renal failure (2 weeks) | 4.4 | CD20+, CD3- | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | No systemic disease found; chemotherapy started |

| 8 | 4/M | Unexplained ARF, acute uric acid nephropathy, oliguria for 7 days | 4 | CD20+, CD3- | Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | Patient died within 5 days (severe hyperuricemia) alive |

| 9 | 27/M | Small joints pain. ARF on hemodialysis | 9.6 mg% | CD 20+, CD3- | B-cell lymphoma | |

| 10 | 11/M | RPRF | 8.0 | CD 20-, CD3+ | T-Acute lymphoblastic lymphoma | Died due to sepsis |

| 11 | 35/M | Diagnosed case of NHL, ARF | 4.8 | CD3+, CD 20- | T-cell lymphoma | Alive, on dialysis |

| 12 | 50/M | Diagnosed case of CLL, RPRF, | 5.5 | CD 20+, CD3- | B-cell lymphoma | Alive, on dialysis |

Cases 3 and 7 are primary renal lymphoma and the others are renal involvement in systemic lymphoma, ARF: acute renal failure, SOL: space occupying lesion, NHL: Non-Hodgkins lymphoma, CT-RT chemo and radiotherapy, RPRF: rapidly progressing renal failure, CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, symbol ‘- ‘is negative, symbol ‘+’: positive, LTFU: lost to follow-up

Among the 12 cases, three patients (cases 2, 6, and 11) had a previous history of non-Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL). One patient (case 12) had a history of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), one other patient (case 3) was a known case of thymoma with a history of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and the other seven patients were new cases diagnosed as lymphoma on kidney biopsy done for renal insufficiency.

Out of the 12 cases, two (cases 3 and 7) were diagnosed as a primary lymphoma of the kidney, and 10 cases were diagnosed as secondary lymphomas [Figure 1].

- Typing of lymphomatous interstitial infiltrate

Kidney biopsy findings

On histology, glomeruli and tubules did not show any evidence of involvement. The interstitium showed widening with lymphomatous infiltration in different patterns.

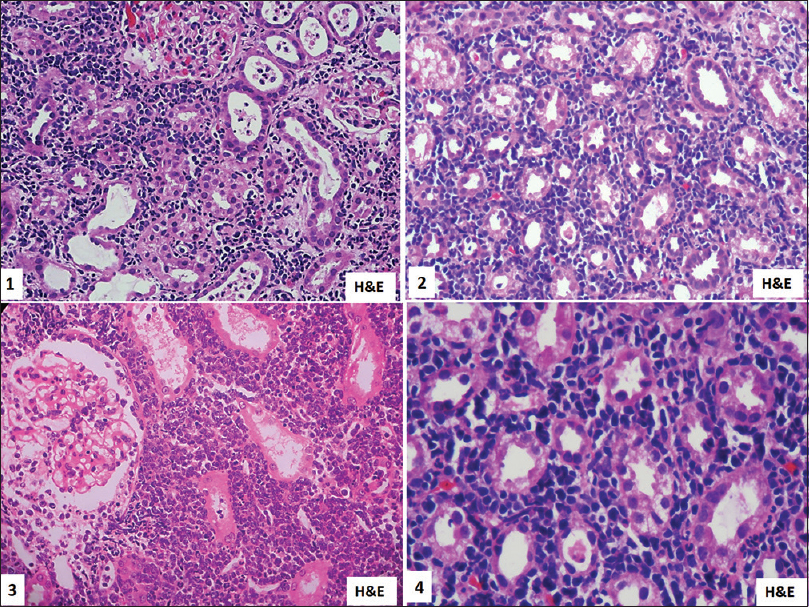

There was a diffuse pattern of lymphomatous infiltration in five cases and patchy infiltration in seven cases [Figure 2] which required further IHC for typing, which was done using CD20 and CD3 immune stains [Figure 3].

- Kidney biopsy showing interstitial involvement by small to medium-sized atypical lymphoid cells. H and E, 1 is ×10, 2 and 3 is ×200, 4 is ×400

- IHC on kidney biopsy shows interstitial lymphomatous infiltrate is CD 20 positive in 1, CD3 positive in 2, TDT positive in 3, occasional CD20 positive in 4, CD3 positive in reactive lymphoid cells, and negative in atypical cells in 5. ×400

The cases were categorized into B- and T-cell lymphoma, of which nine cases were diagnosed as B-cell lymphoma and three cases were diagnosed as T-cell lymphoma Table 2. Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas constituted six cases out of nine. In the T-cell lymphoma category, two were T-cell acute lymphoblastic lymphoma and one a high-grade T-cell lymphoma.

| NHL | Our study (n=12) | Shi-Jun Li[5] (n=20) | L Corlu et al.[6] (n=34) | Tornroth et al.[7] (n=5) | Javaugue et al.[8] (n=52) | Shakeeb Ahmed Yunus et al.[9] (n=19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DLBCL | 41.6% (5) | 20% (4) | 17%(6) | 40% (2) | 15% (8) | 63% (12) |

| NHL B-cell | 16.6% (2) | 10%(MALT MCL each 1)(2) | 17% (6) | 20% (1) | 21% (10) | 21% (4) |

| ILBCL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40% (2) | 1 | 0 |

| WM, myeloma | 0 | 0 | 35% (12) | 0 | 42% (21+1) | 0 |

| CLL | 8.3% (1) | 40% (8) | 29% (10) | 0 | 21% (11) | 0 |

| LPL | 0 | 10% (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| High-grade T-cell lymphoma | 8.3% (1) | 20% (4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15.7% (3) |

| T ALL | 16.6% (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

DLBCL: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, LPL lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, WM-Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, ILBCL- Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, TALL- T-acute lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia, MALT: mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, MCL: mantle cell lymphoma

There were no deposits in the immunofluorescence (IF) study.

Follow up

Patient outcomes in 12 patients were variable, with no follow-up available in four patients. Four patients succumbed following complications [Table 1]; another four patients were alive, of which one was on chemotherapy and two were on hemodialysis.

Discussion

The most common organ infiltrated by leukemia or lymphoma is the kidney, varying from 60% to 90% of patients in an autopsy study.[2] It showed that factors such as sex, age, and disease duration do not have any significant influence on renal lymphomatous infiltration.[3] Kidney dysfunction can have varied presentations, from asymptomatic to severe where renal replacement therapy is required. The intensity of infiltration corresponds to the grade and stage of the disease. There is a varied proportion of kidney infiltration as observed in a series of 1200 autopsy cases in different variants of lymphomas. It was 63% in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), 54% in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 34% in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), and 33% in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).[2]

The prevalence of renal involvement was reported in 34% of patients with Hodgkin's (HL) and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) in an autopsy study of 700 lymphoma patients.[2]

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders are life-threatening complications of solid organ and bone marrow transplant. The risk of lymphoma in kidney transplant recipients was 11.8-fold higher, with a varying incidence of 1%–3% in the first post-transplant year.[5]

AKI from lymphomatous infiltration was seen in only about 1% of acute leukemias and very less in chronic lymphomas.[2]

Symptoms and signs include fever, flank pain, abdominal distension, hematuria, and hypertension.

Some variable clinical features included bilateral kidney enlargement, lymphadenopathy, renal impairment, and proteinuria.[2]

The mechanism behind the acute kidney injury due to lymphomatous infiltration is the diffuse interstitial infiltration of one or both the kidneys by tumor cells. The interstitial infiltration causes tubular and peritubular capillary compression, which leads to obstruction of the tubules and post-glomerular vascular resistance increases.[6]

Primary renal lymphoma (PRL) is extremely rare, with an incidence of 0.7% among the extranodal lymphomas. PRL commonly presents as AKI and hypertension. Biopsy findings show a predominant interstitial lymphomatous infiltrate with less fibrosis and an associated poor prognosis.[2]

In imaging studies, this can be identified as unilateral or bilaterally enlarged kidneys.[6]

Histologically, this atypical infiltrate can be identified based on the architecture of the cells. In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the kidney, diagnoses can be made by virtue of the large atypical cells whereas a diagnosis of a low-grade lymphomatous infiltration can be difficult and can be easily misdiagnosed as interstitial nephritis. Therefore, IHC is required for confirmation and subtyping of the diagnosis.[6]

The renal lymphomatous infiltrate is focal nodular in low-grade lymphoma and is focal in lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma but diffuse and massive in CLL.[7] Chronic lymphocytic leukemia infiltrate can be diffuse and nodular associated with the granulomatous reaction.[2]

However, renal involvement cannot be predicted based on clinical and biochemical features. Thus, kidney biopsy would be required for confirmation of a radiological and clinical suspicion of lymphoma.[7]

This study, which included 12 cases who presented with acute kidney injury, found lymphoma on renal biopsy, either as a part of systemic lymphoma or as a primary renal lymphoma (two cases).

The common presentation was an increase in serum creatinine, which is similar to that of many articles published in the literature.[78910111213141516] Acute kidney injury in lymphoma occurs due to various causes, including infection, obstructive uropathy, uric acid nephropathy, and leukemic infiltration itself contributing to the pathogenesis of renal failure.[12]

Radiological findings were not documented as it was a retrospective observational study.

On histology, renal biopsy revealed interstitial lymphomatous infiltration with diffuse pattern in five cases and patchy pattern in seven cases, which is in contrast to other studies where a diffuse pattern was predominant.[789] The glomeruli and tubules were spared in this study. Based on IHC, lymphomatous infiltrate was further categorized into B- or T-cell type. This study showed a predominance of B-cell type of NHL, similar to other studies [Table 2].[7891011]

Primary lymphoma of the kidney (PRL) is very rare, with mostly single case reports and very few case series available in English literature.[1718192021222324]

PRL has three diagnostic criteria: 1) lymphomatous infiltration in kidney, 2) non-obstructive kidney enlargement in one or both kidneys, and 3) no extrarenal disease.[25]

PRL constitutes less than 1% of the extranodal lymphomas.[26] In our study, two cases of PRL [Table 1] were detected with no other associated systemic disease. On kidney biopsy, one was diagnosed as a high-grade T-cell lymphoma, and the other case was diagnosed as a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, which was similar to other studies on primary renal lymphomas.[1718192021222324]

In this study, of the 10 cases of secondary renal lymphomas, few had other associated clinical findings as described in Table 1. All the cases presented with acute kidney injury with increased serum creatinine, similar to that of various articles published in the literature,[178910111213141516] and were categorized into different variants of lymphomas [Table 2].

Glomeruli and other compartment changes were nonspecific in our study, unlike other series where there were glomerulopathies and tubulointerstitial injury.[78] Few studies such as Shi-Jun Li et al. (40%)[8] had a predominance of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, whereas other cohorts of Corlu et al. (29%)[7] and Javaugue et al. (21%)[9] had a predominance of Waldenström macroglobulinemia followed by chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

In this study, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma was the dominant type, constituting50% of the total cases of lymphomas, whereas other authors, namely Corlu et al.[7] had 17%, Shi-Jun L et al.[8] had 20%, Javaugue et al.[9] had 15%, Yunus et al.[10] had 63%, and Tornroth et al.[11] had 40%, of documented DLBL in their case series.

T-cell lymphomas were less common, being approximately 20% in this study, which is similar to the other studies by Shi-Jun L et al. [8] (20%) and Yunus et al. (15.7%).[10]

Intravascular large B-cell lymphomas were observed in approximately 40% by Tornroth et al.[11] and were not seen in this study.

Patients had varied clinical outcomes. Among the 12 cases, four patients were lost to follow-up, of which one was a primary renal lymphoma and three had secondary lymphomatous involvement. The duration of the disease ranged from 5 to 30 days in the patients available for follow-up. Among these eight patients, one child died within 3 weeks of diagnosis (case 1), another patient (case 4) died within 1 month of diagnosis due to central nervous system bleed, a 4-year-old child (case 8) died within 5 days due to severe hyperuricemia, and another 11-year-old boy (case 10) died due to sepsis.

In the study of L Corlu et al.[7] the median survival was 29 months (0.7–119.2 months) and on follow-up, 12 patients (35.3%) died due to various hematological reasons (41.7%), end-stage renal disease (25%), cardiorespiratory disease (25%), and other malignancies (8.3%).

In the series of Shi-Jun Li et al.[8] nine patients died. Three of these had T/NK-cell lymphoma who succumbed to secondary infection while on chemotherapy, and six died within 2 years of diagnosis. In the cohort of Javaugue et al.,[9] 20 patients (38%) died after a median follow-up of 21 months (range: 2–144 months) from the day of diagnosis. Causes of death were infection (n = 6), hematological relapse/progression (n = 6), cardiovascular disease (n = 3), or unknown causes (n = 5).

In this study, four patients out of 12 were alive on last follow-up, with two being on dialysis and one undergoing chemotherapy. In the study by Shi-Jun Li et al,[8] three cases had normal serum creatinine, five patients had stable renal function or, after chemotherapy, they improved and permanent hemodialysis was required as in one patient.

All these studies indicate that a diagnosis of renal lymphomas, either primary or secondary, has a poor prognosis. Kidney biopsy has two roles, one is to know the location of infiltration and its extent which can influence prognosis, and another is to identify the subtype of lymphoma or leukemia which determines the course of the treatment and the disease.[2]

Identification of lymphomatous infiltrate on kidney biopsy is critical and needs expertise; when it is patchy and focal, it is challenging, especially when it is a low-grade lymphoma requiring clinical correlation and extensive IHC workup to differentiate from reactive lymphomononuclear cells in the interstitium. However, a timely renal biopsy can confirm the diagnosis, allowing early institution of therapy. Thus, awareness of this entity enables early correct diagnosis and effective therapy to improve patient survival.

Conclusions

Lymphomatous infiltrate of the kidney can cause acute kidney injury. The diagnosis can be suspected on light microscopy by paying attention to the cellular details of the infiltrating cells and can be confirmed with a panel of immune stains. Systemic work up is necessary as acute renal insufficiency may be the primary manifestation of systemic lymphoma. Kidney biopsy is therefore essential for a diagnosis of renal lymphoma, especially in primary renal lymphoma, to institute early treatment and for benefit of cure in patients. Second, it helps identify the exact subtype of hematolymphoid malignancy to ensure appropriate treatment. However, most publications of acute kidney injury in renal lymphoma constitute single case reports. To the best of our knowledge, not many case series like this study have been published in English literature.

Rarely, kidney infiltration has been reported in acute myeloid leukemia and in the post-transplant setting in the form of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, though not seen in this small series.[2]

A high index of suspicion is required to identify lymphoma cells with IHC, and a multidisciplinary approach is warranted for appropriate treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Renal Diseases Associated with Hematologic Malignancies and Thymoma in the Absence of Renal Monoclonal Immunoglobulin Deposits. Diagnostics. 2021;11:1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney involvement in leukemia and lymphoma. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014;21:27-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma presenting as primary renal lymphoma with acute renal failure. NDT Plus. 2011;4:289-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in adult renal transplant recipients: case series and review of literature. Cent Eur J Immunol. 2020;45((4)):498-06.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney injury and disease in patients with haematological malignancies. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17:386-401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal Dysfunction in Patients with Direct Infiltration by B-Cell Lymphoma. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4:688-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal Involvement in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Proven by Renal Biopsy. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathological spectrum of renal parenchymal involvement in B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders. Kidney Int. 2019;96:94-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal involvement in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: the Shaukat Khanum experience. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8:249-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphomas diagnosed by percutaneous kidney biopsy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:960-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure due to lymphomatous infiltration of the kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1348-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia presenting with acute renal failure: report of two cases. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:512-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary bilateral T-cell renal lymphoma presenting with sudden loss of renal function. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:1487-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The spectrum of kidney involvement in lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:1191-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary renal lymphoma: a case report and literature review. Intern Med. 2015;54:2655-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary renal lymphoma does exist: case report and review of the literature. J Nephrol. 2000;13:367-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure due to lymphomatous infiltration: an unusual presentation. In: Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. Vol 17. Mumbai, India: Medknow Publications Pvt. Ltd; 2006. p. :395-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapidly progressive renal failure due to tubulointerstitial infiltration of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified accompanied by uveitis: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Presenting with Bilateral Renal Masses and Hematuria: A Case Report. Turk J Haematol. 2016;33:159-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary renal lymphoma: unique presentation in a rare disease. J Surg Case Rep. 2021;3:1-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary renal lymphoma: An incidental finding in an elderly male. Urol Case Rep. 2019;26:1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary renal lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. AME Case Rep. 2020;4:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enormous primary renal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2019;47:2728-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary renal lymphoma: a population-based study in the United States, 1980-2013. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]