Translate this page into:

Association of Acute Kidney Injury with Ammonia Poisoning: A Case Report

Corresponding author: Abhilash Chandra, Department of Nephrology, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Institute of Medical Sciences, Gomti Nagar, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: acn393@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Pooniya V, Chandra A, Rao S N, Singh AK, Malhotra KP. Association of Acute Kidney Injury with Ammonia Poisoning: A Case Report. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:395-7. doi: 10.25259/IJN_9_21

Abstract

Ammonia may cause poisoning due to inhalation or ingestion. Renal involvement in ammonia poisoning has been reported only once. A 30-year-old male working in an ice factory was accidentally exposed to liquid ammonia from a leaking hose, following which he had burns over his face and neck and severe abdominal pain. On day 2, he had deranged renal function, which was progressive. He was referred to us due to persistent renal dysfunction. A kidney biopsy was performed due to slow recovery of renal failure, which was suggestive of acute tubular necrosis. He was managed conservatively and showed gradual improvement over 12 days of his hospital stay. Renal functions normalized after 14 days of discharge. This case highlights the occurrence of renal involvement in ammonia poisoning.

Keywords

Acute Kidney Injury

Ammonia

Poisoning

Introduction

Ammonia is a colorless, pungent, and irritant caustic gas.1,2 It is stored and transported as a pressurized liquid.2 Poisoning may occur due to inhalation or ingestion and leads to local burns, gastrointestinal (GI) or respiratory manifestations, altered sensorium, shock, and even death. The first report of poisoning due to inhalation of ammonia was published in 1841, and since then, there have been various reports of ammonia poisoning and burns, but renal failure due to ammonia poisoning has been reported only once in the literature.3,4 We report a case of accidental ammonia poisoning which led to acute kidney injury (AKI).

Case Report

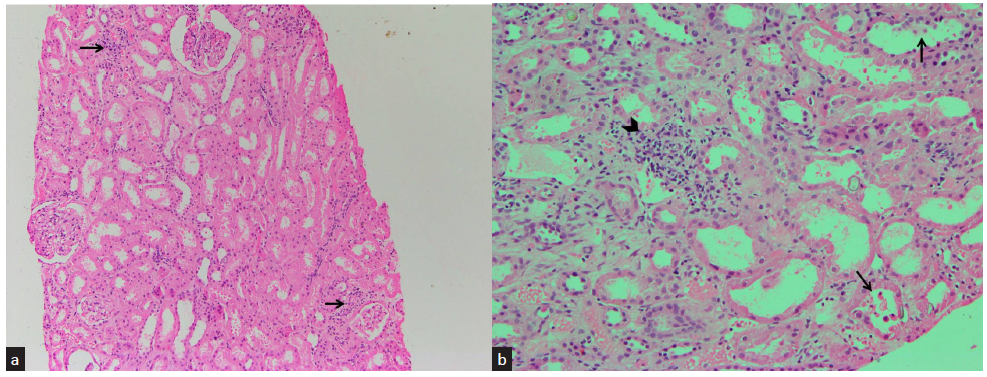

A 30-year-old male who was working in an ice manufacturing factory in North India got accidentally exposed to liquid ammonia while attempting to repair a leaking hose. He developed burns over face, neck, and oral cavity, along with severe abdominal pain. He was taken to a local hospital where he was managed with proton pump inhibitors, drotaverine, and intravenous (iv) fluids. On day 2, he was found to have renal dysfunction (serum creatinine 2.1 mg/dl), although he did not have oliguria. Renal dysfunction was progressive, and serum creatinine rose to 8.2 mg/dl on day 7. He was given three sessions of hemodialysis over the next 7 days, and then he was referred to us for persistent renal failure. There was no history of vomiting, loose stools, or intake of nephrotoxic drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], aminoglycosides, etc.). His medical records did not reveal any evidence of hypotension during his previous hospitalization, nor was any arterial blood gas analysis report available. On admission, he was afebrile and normotensive (blood pressure [BP] 122/80 mmHg). There were multiple shallow ulcers over lips and buccal mucosa, with superficial healing burns over nose, perioral region, and left side of neck. He had no respiratory distress or edema. Examination of chest, cardiovascular system, nervous system, and abdomen was unremarkable. His hemoglobin was 12 g%, total leucocyte count (TLC) was 7600/µl with 75% polymorphs and 21% lymphocytes, and platelet count was 1.51 lacs/µl. His serum chemistry revealed urea 164 mg%, creatinine 5.9 mg%, sodium 141 mEq/l, and potassium 3.57 mEq/l. Liver function tests, serum complements (C3 and C4), and serum creatine phosphokinase were within normal limits. Urine sediment was bland, and ultrasound of abdomen was also unremarkable. Upper GI endoscopy revealed multiple superficial erosions in esophagus and stomach. He was managed conservatively with H2 blockers and antispasmodics with local application of choline salicylate and benzalkonium chloride gel over buccal mucosa. Two sessions of hemodialysis were given over the first 3 days of admission. After 1 week of admission, serum creatinine was 3.9 mg/dl; hence, a kidney biopsy was performed due to a very slow recovery of renal function. On light microscopy, 13 glomeruli were seen, which were unremarkable. Tubules showed focal epithelial cell denudation and occasional red blood cell casts. There was a mild lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with normal blood vessels [Figure 1]. On immunofluorescence, 10 glomeruli were visualized, which did not show any deposits of IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, or C1q. Hence, a possibility of acute tubular necrosis was kept. His pain abdomen gradually resolved. Renal function and urine output gradually improved during hospital stay. After 12 days of hospital stay, he was discharged with a serum creatinine of 2.03 mg/dl. During follow-up, his serum creatinine normalized (0.82 mg/dl) after 14 days of discharge.

- Section from renal biopsy shows (a) unremarkable glomeruli and scant lymphocytic interstitial infiltrate (black arrows) (hematoxylin and eosin, ×100) and (b) tubular epithelial cell denudation (black arrows) and lymphocytic interstitial infiltrate (black arrowhead) (Hematoxylin and Eosin, ×200)

Discussion

One of the important causes of AKI is toxins, both endogenous as well as exogenous. Endogenous toxins causing AKI include hemoglobin (hemolysis), myoglobin (rhabdomyolysis), and uric acid (tumor lysis syndrome). Exogenous toxins leading to AKI include various drugs, radiocontrast agents, nephrotoxic plants, animal poisons, chemicals, and illicit drugs.5

Ammonia is an irritating and caustic gas and is water soluble, which is used as a refrigerant, in fertilizers, and as a cleaning agent.1,6 Poisoning may occur by inhalation or ingestion. On exposure to liquid ammonia, local effects may include burns, mouth and throat pain, abdominal pain, dysphagia, and drooling of saliva. If inhalation has occurred, it may cause airway injury. Shock and death have been reported on inhalation of large amounts.1,7,8 Our patient had small superficial burns over face, neck, and oral mucosa due to exposure to liquid ammonia, along with severe abdominal pain, but there was no respiratory symptom or sign. Upper GI endoscopy also revealed esophageal erosions; hence, the most probable route of exposure was through ingestion in this case. Renal failure due to ammonia poisoning has been reported only once in literature, where a 69-year-old woman ingested 3% ammonia leading to aspiration pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and renal failure and died after several days.3 But the authors did not report whether kidney biopsy was done or not. Ours is the second case where patient developed AKI after ammonia toxicity and the first case in literature where renal pathological findings have been described.

Mechanism of nephrotoxicity of ammonia may be multifactorial. Ammonia may interact with the C3 complement component and stimulate production of reactive oxygen species by neutrophils and monocytes.9 N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor activation may also contribute to nephrotoxicity of ammonia.10 Perfusion of dog kidneys with ammonium salts has been shown to lead to cortical and tubular necrosis and decreased glomerular filtration rate.11 We were unable to find any animal model of ammonia nephrotoxicity without encephalopathy. Serum ammonia levels were normal in this case, but already 14 days had elapsed since exposure and the patient had received four sessions of hemodialysis before coming to us.

Conclusion

This case suggests renal involvement can occur in association with ammonia poisoning and the treating physicians should watch the renal functions in such cases, because early recognition and timely treatment of AKI leads to better outcomes. Acute tubular necrosis may be caused by multiple factors, but we were unable to find any other factor in this case (e.g., hypovolemia/shock, exposure to any other toxin, etc.). Although the exact mechanism of nephrotoxicity of ammonia is unknown, it isn’t easy to elucidate it because of the rarity of its occurrence.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- A Non-accidental poisoning with ammonia in adolescence. Child Care Health Dev. 2005;31:737-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anhydrous ammonia burns case report and review of literature. Burns. 2000;26:493-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caustic injury from household ammonia. Am J Emerg Med. 1985;3:320.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- On poisons in relation to medical jurisprudence and medicine (3rd ed). Philadelphia: Lea; 1875.

- Acute toxic kidney injury. Ren Fail. 2019;41:576-94.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Our chemical burn experience: Exposing the dangers of anhydrous ammonia. J Burn Care Rehab. 1999;20:226-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Airway obstruction due to inhalation of ammonia. Mayo Clin Proc. 1983;58:389-93.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amidation of C3 at the thiolester site: Stimulation of chemiluminescence and phagocytosis by a new inflammatory mediator. J Immunol. 1985;134:3339-45.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerebral oedema is not responsible for motor or cognitive deficits in rats with hepatic encephalopathy. Liver Int. 2014;34:379-87.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Some effects of ammonium salts on renal histology and function in the dog. Nephron. 1976;16:42-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]