Translate this page into:

Catheter-related Infections and Microbiological Characteristics in Coiled Versus Straight Peritoneal Dialysis Catheters in Malaysia

Address for correspondence: Dr. Anna M. Abdul Rashid, Department of Medicine, Level 3, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia. E-mail: annamisyail@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Background:

Catheter-related infections remain a threat in peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients. Attempts to improve catheter insertion techniques and catheter type with best infectious outcomes yield heterogenous results. We seek to determine catheter-related infections in two different types of catheters and its microbiological spectrum.

Methods:

Retrospective cross-sectional study conducted in Hospital Serdang, Malaysia. We included end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients who opted for PD and examined catheter-related infections (peritonitis, exit site infection, and tunnel tract infection) and organisms causing these infections.

Results:

We included 126 patients in this study; 75 patients received the coiled PD catheter (59.5%) and 51 patients received the straight PD catheter (40.5%). The majority of patients were young, under the age of 65 years old (77.3% and 72.5%) in the coiled and straight PD catheter group, respectively, and the main cause of ESRD was diabetes mellitus in both groups (78.7% vs. 92.2%). The demographic and anthropometric data were similar between both groups. Peritonitis rate (0.29 episodes/patient-years vs. 0.31 episodes/patient-years, P value = 0.909), exit site infection rate (0.31 episodes/patient-year vs. 0.37 episodes/patient-year, P value = 0.730), and tunnel tract infection rate (0.02 episodes/patient-year, P value = 0.430) were similar in the coiled versus straight PD catheter groups. The predominant organism causing peritonitis was the gram-negative organism; Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. In exit site and tunnel tract infections, there is a predominance of gram-negative organisms; Pseudomonas aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae.

Conclusions:

There was no difference in infectious outcomes between the two different types of catheters. Type of organism in both groups was gram-negative.

Keywords

Exit site infection

microbiological spectrum

peritoneal dialysis

peritonitis

tunnel tract infection

Introduction

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is becoming a more popular choice of renal replacement therapy (RRT) not only owing to its renal protective effects[12] but also conferring patient empowerment and autonomy.[34] Despite improvements in insertion techniques and catheter designs, catheter-related infection continues to be a great source of morbidity and remains a barrier to a successful PD program. This includes peritonitis, exit site infection (ESI) as well as tunnel tract infections (TTI).

While a lot of attention is being spent on the natural history and causative organisms in peritonitis, ESI and TTI impose a similar threat to a PD program. Understanding the microbial spectrum of organisms that occur within these catheter-related infections is important as geographical variations are common worldwide. Therefore, developing a guideline based on local epidemiological and microbial data will empower health-care workers to successfully treat these infections.

Existing evidence suggested no difference in infectious complications between different types of catheters.[5678] However, most of these data are limited by its retrospective nature and small sample size. Furthermore, there is a lack of data comparing the microbial spectrum between the two types of catheter. In this study, we evaluated the different catheter-related infections in PD patients as well as its microbiological characteristics in our center as a means of continuous quality improvement to strengthen our center's success in PD programs.

Method

This is a retrospective study conducted in Hospital Serdang, Malaysia, which is a tertiary center that specializes in Nephrology. We included 126 end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients who required catheter insertion for PD between August 2008 and December 2010. They were assigned to receive a coiled PD catheter versus a straight PD catheter based on the discretion of treating nephrologist during initial assessment according to patients' suitability. The incidence of catheter-related infections which includes peritonitis, ESI, and TTI for these patients were collected in the period of 124 months, from August 1, 2008 to December 30, 2018.

All PD catheters were inserted by a nephrologist using the peritoneoscopic method under conscious sedation, where intravenous (IV) sedation and analgesia such as midazolam and fentanyl are given during the procedure. The catheters utilized were doubled cuffed, coiled, and straight PD catheters at 57.5 cm and 47 cm, respectively. Standard catheter care with mupirocin cream and povidone iodine were employed and IV cefazolin was given as prophylactic antibiotics. Ambulatory PD was delayed for at least 2 weeks after insertion.

A standardized data collection sheet to record patient details, comorbidities as well as the occurrence of infection (peritonitis, ESI, and TTI) was used, and data were retrieved from our computerized system by trained medical personnel. The primary outcome of this study was catheter-related infections in PD patients, which include peritonitis, ESI, and TTI infection rates. We also studied the causative organism causing these infections to examine whether the type of catheter causes different microbiological characteristics in our patients.

Peritonitis was defined as presence of at least two out of three criteria: (i) signs and symptoms of peritonitis, (ii) cloudy dialysate with white cell count of 100/μL, or (iii) demonstration of organism by PD fluid culture. A peritonitis that occurred within 4 weeks of the previous episode of peritonitis was considered a relapse, thus not classified as a new infection. ESI was the presence of purulent discharge, with or without erythema of the skin at the catheter-epidermal interface.[9] TTI was the presence of clinical inflammation or ultrasonographic evidence of collection along the catheter tunnel.[9] If the diagnosis of peritonitis was fulfilled, PD fluid sample was taken and sent to the laboratory for culture and sensitivity. For ESI and TTI, a swab and blood sample were taken and sent to the laboratory for examination of microbiological spectrum and organism sensitivity.

Inclusion criteria were all patients above the age of 18 with a diagnosis of ESRD who opted for PD (continuous ambulatory PD and automated PD). Patients who had a PD catheter for intermittent PD while awaiting vascular access or those who were referred from another center were excluded. This study was reviewed and approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee of Health Ministry of Malaysia (NMRR-18-865-41205) on July 12, 2018.

Data entry and analyses were done using SPSS version 20, on an intention-to-treat basis. Numerical variables were checked for normality distribution, and appropriate measures of central dispersion were used to describe the data. It was presented in mean (SD), and independent t-test was used to compare means of two groups. Categorical variables were presented in frequencies and percentages. Chi-square test was used to examine associations. A p value of <0.05 level of significance was considered.

Results

Patient characteristics

We included 126 patients in this study; 75 patients received the coiled PD catheter (59.5%) and 51 patients received the straight PD catheter (40.5%). The majority of patients were young under the age of 65 years old (77.3% and 72.5%) in the coiled and straight PD catheter group, respectively. The mean age between the two groups was similar, 49.9 ± 16.79 years in the coiled PD catheter group and 53.4 ± 14.67 years in the straight PD catheter group (P-value = 0.173). In both groups, the majority of patients were male (53.3% vs. 56.9%, P value = 0.696). The anthropometry data were similar between both coiled and straight PD catheter group. The main cause of ESRD was diabetes mellitus in both groups (78.7% vs. 92.2%, P value = 0.049). Table 1 represents the patients' demographical characteristics.

| Coiled (n=75) | Straight (n=51) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.4 (16.79) | 53.4 (14.67) | 0.173 |

| Male | 40 | 29 | 0.696 |

| Race | |||

| Malay | 42 | 31 | 0.034 |

| Chinese | 21 | 19 | |

| Indian | 12 | 1 | |

| Height (cm) | 157.2 (10.88) | 158.6 (9.5) | 0.438 |

| Weight (kg) | 58.0 (14.10) | 60.4 (12.49) | 0.349 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.18 (5.32) | 23.1 (4.02) | 0.946 |

| Cause of ESRDa | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 59 | 47 | 0.049 |

| Hypertension | 3 | 2 | 1.000 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 10 | 0 | 0.006 |

| Obstructive uropathy | 1 | 1 | 1.000 |

| Unknown | 1 | 1 | 1.000 |

aEnd-stage renal disease

Peritonitis and causative organisms

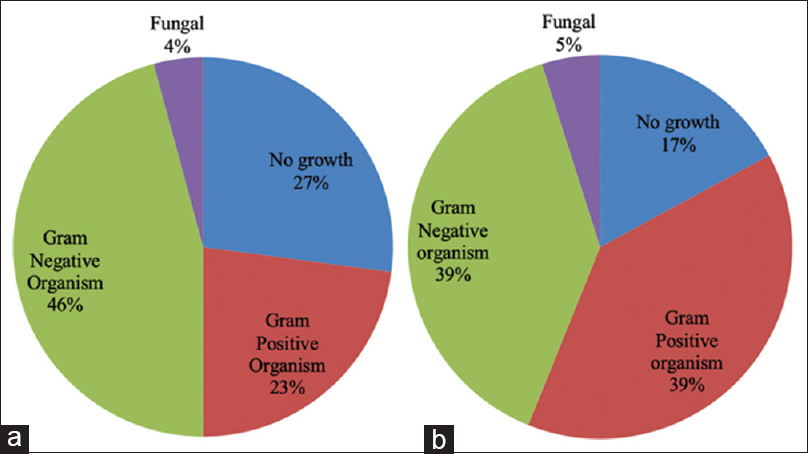

In the coiled PD catheter group, the peritonitis rate was 0.29 episodes/patient-years and in the straight PD catheter group the peritonitis rate was 0.31 episodes/patient-years (P-value = 0.909). There were 48 episodes of peritonitis in the coiled PD catheter group and 41 episodes of peritonitis in the straight PD catheter group [Table 2]. In the coiled PD catheter group, gram-negative organisms were grown in 22 isolates (45.8%), most commonly E. coli, accounting for 16.7%. Eleven episodes (22.9%) grew gram-positive organisms, the most common isolate was Methicillin Sensitive Staphylococcus aureus accounting for 6.3%. There were two episodes of fungal peritonitis (4.2%), growing mostly Candida albicans (C. albicans). Thirteen episodes (27.1%) were culture negative peritonitis [Figure 1a]. In the straight PD catheter group, the proportion of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms causing peritonitis was similar, 16 episodes each (39%). However, the most common gram-negative organism was K. pneumoniae, accounting for seven (17.1%) while the most common gram-positive organism was methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis, accounting for four episodes (9.8%). The fungal peritonitis was similar to the coiled catheter group, two episodes (4.9%) growing C. albicans and culture-negative peritonitis constituted seven episodes (17.1%) [Figure 1b].

| Organism | Coiled n (%) | Straight n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No growth (NG) | 13 (27) | 7 (17.1) |

| MSSA (GP) | 3 | 2 |

| MRSA (GP) | 1 | 2 |

| MRSE (GP) | 2 | 4 |

| Staphylococcus coagulase negative (GP) | 0 | 1 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae (GP) | 0 | 1 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes (GP) | 0 | 1 |

| Streptococcus viridans (GP) | 1 | 2 |

| Streptococcus bovis (GP) | 1 | 0 |

| Streptococcus agalactiae (GP) | 1 | 0 |

| Streptococcus salivarius (GP) | 0 | 1 |

| Streptococcus parasanguinis (GP) | 0 | 1 |

| Group B Streptococcus (GP) | 1 | 1 |

| Bacillus cereus (GP) | 1 | 0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (GN) | 1 | 7 |

| Klebsiella ozaenae (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| ESBL Klebsiella pneumoniae (GN) | 1 | 1 |

| Escherichia coli (GN) | 8 | 4 |

| Enterobacter cloacae (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (GN) | 1 | 3 |

| Burkholderia pseudomallei (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Serratia marcescens (GN) | 2 | 1 |

| Proteus mirabilis (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Citrobacter freundii (GN) | 2 | 0 |

| Citrobacter kaferii (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Shewanella putrefaciens (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Candida albicans (fungal) | 2 | 2 |

| Total NG | 13 (27.1) | 7 (17.1) |

| Total GP | 11 (22.9) | 16 (39) |

| Total GN | 22 (45.8) | 16 (39) |

| Total fungal | 2 (4.2) | 2 (4.9) |

| Total episodes | 48 (100) | 41 (100) |

NG-no growth, GN-gram-negative, GP-gram-positive, MSSA-methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSE-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis

- (a) Organisms causing peritonitis in the coiled PD catheter and (b) organisms causing peritonitis in the straight PD catheter

Exit site infections and Tunnel tract infections

The ESI rate was similar between both groups, 0.31 episodes/patient-year in the coiled PD catheter group and 0.37 episodes/patient-year in the straight PD catheter group (P-value = 0.730). However, the number of surgical interventions (deroofing of ESI) required in the coiled PD catheter group was higher than in the straight PD catheter group, 16 (31.4%) versus 8 (10.7%), respectively (P-value = 0.005). In both groups, we observed higher episodes of gram-negative organisms, 21 (51.2%) versus 20 (52.6%) in the coiled and straight PD catheter groups, respectively [Figure 2a and 2b]. The most common gram-negative organism was P. aeruginosa followed by K. pneumoniae. There was no fungal organism isolated in the straight PD catheter group, while the coiled PD catheter group has one episode (2.4%) of fungal organism, which grew C. albicans. There were 10 episodes (24.4%) versus 8 episodes (21.1%) of culture negative ESI in the coiled and straight PD catheter group, respectively [Table 3].

- (a) Organisms causing exit site infection in the coiled PD catheter and (b) organisms causing exit site infection in the straight PD catheter

| Organism | Coiled n (%) | Straight n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No growth (NG) | 10 (24.4) | 8 (21.1) |

| MSSA (GP) | 5 | 4 |

| MRSA (GP) | 1 | 0 |

| MRSE (GP) | 3 | 3 |

| Enterococcus faecalis (GP) | 0 | 1 |

| Micrococcus luteus (GP) | 0 | 1 |

| GPC (GP) | 0 | 1 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (GN) | 5 | 2 |

| Escherichia coli (GN) | 0 | 3 |

| ESBL Escherichia coli (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Enterobacter cloacae (GN) | 1 | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (GN) | 7 | 7 |

| Pseudomonas putida (GN) | 0 | 1 |

| Burkholderia cepacia (GN) | 0 | 1 |

| Serratia marcescens (GN) | 2 | 1 |

| Proteus mirabilis (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Citrobacter freundii (GN) | 0 | 1 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii (GN) | 1 | 1 |

| Providencia rettgeri (GN) | 0 | 1 |

| Sphingomonas paucimobilis (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Morganella morganii (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| GNR (GN) | 1 | 1 |

| Candida albicans (fungal) | 1 | 0 |

| Total NG | 10 (24.4) | 8 (21.1) |

| Total GP | 9 (22) | 10 (26.3) |

| Total GN | 21 (51.2) | 20 (52.6) |

| Total fungal | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) |

| Total episodes | 41 (100) | 38 (100) |

NG-no growth, GN-gram-negative, GP-gram-positive, MSSA-methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSE-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis, GNR-gram-negative rod, GPC-gram-positive cocci

The rate of TTI was similar between both groups, 0.02 episodes/patient-year (P-value = 0.430). The majority of TTIs were caused by gram-negative organisms, 2 (50%) in each group. Table 4 shows the causative organisms causing TTI in both groups.

| Organism | Coiled n | Straight n |

|---|---|---|

| No growth (NG) | 1 | 1 |

| MSSA (GP) | 1 | 1 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (GN) | 1 | 1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (GN) | 0 | 1 |

| ESBL Escherichia coli (GN) | 1 | 0 |

| Total NG: 1 | NG: 1 | |

| Total GP: 1 | GP: 1 | |

| Total GN: 2 | GN: 2 | |

| Total Fungal: 0 | Fungal: 0 | |

| Total episodes | 4 | 4 |

NG-no growth, GN-gram-negative, GP-gram-positive

Discussion

The most common catheter-related complication is attributed to infections, where peritonitis accounts for 61%, while ESI and TTI make up 23%.[10] This is not surprising as ESRD patients are chronically immunosuppressed due to chronic inflammation and uremia,[11] rendering them susceptible to infections. While a lot of studies attempted to determine the best insertion technique and catheter type to improve infectious outcomes, the results are heterogenous.[567812] Thus, current guidelines do not favor either method of insertion or specific catheter designs when determining the best PD access.[1314] Instead, an emphasis has been made to encourage each center to have a dedicated team for PD, developing clear protocols for perioperative measure as well as adequate patient training and education as essentials in reducing overall incidence of peritonitis.[15]

In our study, the peritonitis rate in coiled and straight PD catheter is similar (0.29 episodes/patient-year vs. 0.31 episodes/patient-year). The most commonly isolated organism seen in both groups was from the gram-negative strain, E. coli and K. pneumoniae. Overall, gram-negative infections were more common in this series. It is contrary to worldwide reports,[1617181920] except a few. As such, Prasad et al.[21] described a predominance of gram-negative organisms as the cause of peritonitis in India, reporting a worse outcome. Another retrospective study in Sarawak, Malaysia, reported similar occurrence of gram-negative and gram-positive organisms causing peritonitis, with trend of increasing gram-negative infection with time, causing higher rate of catheter loss.[22]

Both of these organisms are commensals of the normal bowel flora that contaminated the sterile peritoneal cavity. We found that most of our patients had a breach in sterile procedure and were not practicing good hand hygiene; thus, these organisms are most possibly of the fecal origin. Hygiene is still a major problem in developing countries where most of our patients were from the working class and lower middle class. This also explained our findings of gram-negative organisms originating from the soil, including Serratia marcescens, Proteus mirabilis, and Citrobacter freundii.

In our study, the coiled catheter group had more gram-negative peritonitis as compared to straight group. Another possible mechanism of infection of these gram-negative bowel floras is from the transmural migration. Several studies have noted a significant trend of tip migration and catheter dysfunction in the coiled PD catheter[723] that could have aggravated inflammatory process, thus promoting transmural bacteria migration. The straight catheter group on the other hand had more gram-positive peritonitis, mostly from the Staphylococci species that is likely due to touch contamination of organisms from the cutaneous origin.

ESI rate was similar in both groups (0.31 episodes/patient-year vs. 0.37 episodes/patient-year, P value = 0.730). Interestingly, the most common organism causing ESI in both groups was P. aeruginosa, a commonly found pathogen in hospital-acquired infections. This could be explained by the fact that ESIs in our hospital were treated with deroofing, which involved surgical procedure to expose and shave the external cuff.[9] As this procedure required use of the operation theater, most of our patients required admission to the ward, thus increasing the risk to hospital-acquired infections.

TTI rate was similar in both groups (0.02 episodes/patient-year in both groups, P value = 0.430). Gram-negative organisms causing peritonitis and ESI were also found to cause more TTI, namely, K. pneumoniae and P. aeruginosa.

Conclusion

There was no difference in infectious outcomes between the two different types of catheters. The spectrum of organism is also similar in both groups of catheters, which are of the gram-negative group.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mortality studies comparing peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: What do they tell us? Kidney Int Suppl 2006:S3-11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001910

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of dialysis treatment modality on the decline of remaining renal function. ASAIO Trans. 1991;37:598-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life and emotional distress between patients on peritoneal dialysis versus community based hemodialysis. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:57-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changes in quality of life during hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis treatment: Generic and disease specific measures. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:743-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparison of two types of catheters for continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) Perit Dial Int. 1990;10:63-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized controlled trial of coiled versus straight swan-neck Tenckhoff catheters in peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:812-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparing the incidence of catheter-related complications with straight and coiled Tenckhoff catheters in peritoneal dialysis patients-A single-centre prospective randomized trial. Perit Dial Int. 2015;35:443-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catheter-related interventions to prevent peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:2735-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- ISPD catheter-related infection recommendations: 2017 update. Perit Dial Int. 2017;37:141-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Peritoneal dialysis associated infections: An update on diagnosis and management. World J Nephrol. 2012;1:106-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of uraemia on structure and function of immune system. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22:149-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study on using coiled versus straight swan-neck Tenckhoff catheters in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Iran J Med Sci. 2008;33:169-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caring for Australasians with Renal Impairment (CARI), Type of peritoneal Dialysis Catheter 2010 :1-9.

- ISPD position statement on reducing the risks of peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Perit Dial Int. 2011;31:614-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictor factors of peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis. J Bras Nefrol. 2010;32:156-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microbial spectrum and outcome of peritoneal dialysis related peritonitis in Qatar. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21:168-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of culture isolates from peritoneal dialysis peritonitis patients in southern India using an automated blood culture system to culture peritoneal dialysate. Nephrology (Carlton). 2011;16:63-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- The surgical management of peritoneal dialysis catheters. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:190-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of gram-positive and gram-negative peritonitis in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: A single-center experience. Perit Dial Int. 2003;23(Suppl 2):S144-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Causative organisms and outcomes of peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis in Sarawak General Hospital, Kuching, Malaysia: A 3-year analysis. Ren Replace Ther. 2017;3:35.

- [Google Scholar]

- A randomized clinical trial comparing the function of straight and coiled Tenckhoff catheters for peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25:85-90.

- [Google Scholar]