Translate this page into:

Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Etiology in Telangana: Is It Different?

Corresponding author: Manisha Sahay, Department of Nephrology, Osmania General Hospital, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: drmanishasahay@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Ramavajula A, Sahay M, Ismal K, Kavadi A, Enganti R, Gowrishankar S. Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Etiology in Telangana: Is It Different? Indian J Nephrol. doi: 10.25259/IJN_257_2024

Abstract

Background

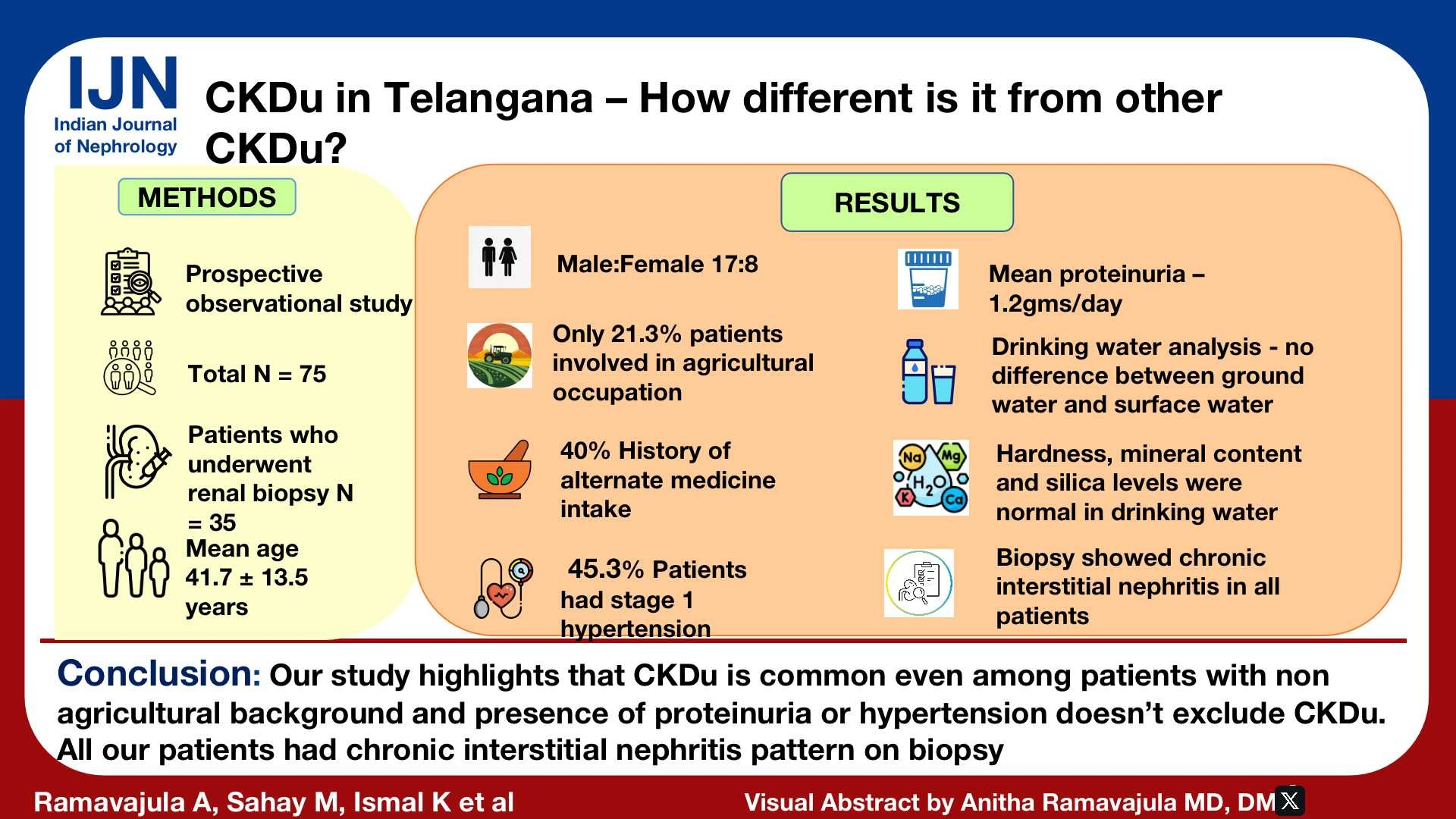

Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) is emerging as an important cause for CKD in various parts of the world, including India. This study was done to determine the risk factors and histology of CKDu in Telangana, a neighboring state of Andhra Pradesh that has CKDu hotspots.

Materials and Methods

This prospective observational study was done from March 2021 to November 2022 at a tertiary care center in Hyderabad. Patients were included as per the Indian CKDu definition. Sociodemographic data, examination, and investigations were obtained. Drinking water was analyzed. Patients with preserved kidney sizes underwent kidney biopsy. Patients were followed up with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at 0.6 months and one year.

Results

A total of 75 patients were studied. Mean age was 41.72 +/- 13.59 years, where 68% were males. Groundwater was the drinking water source for 77.3%. In all, 40% had consumed alternate medicine and 46.6% patients had undergone kidney biopsy. The main findings were global glomerulosclerosis (>50%) in 54%, 31% had >50% interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, 34.3% had periglomerular fibrosis, and 85.7% had interstitial inflammation. Hypertension was a significant risk factor for progression.

Conclusion

Our study results were like other Indian studies in terms of affecting younger male population, but differed from these studies as the majority of our patients came from nonagricultural backgrounds. Herbal medicine intake was a major risk factor. A vast majority of patients had chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in biopsy at presentation, showing that most presented late.

Keywords

CKDu

Chronic interstitial nephritis

Herbal medicine

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology (CKDu) is emerging as an important cause of CKD in India.1 The term CKDu was first used in El Salvador to describe a disease predominantly affecting agricultural communities. Later, several parts of the world reported CKDu.2 Various hypotheses have been proposed in different geographical locations. These include heat stress, drinking water contamination, especially with high silica and fluoride levels, pesticide exposure, herbal and native medicine intake, leptospirosis infection, and other genetic factors.3 There is paucity of data on the epidemiology, clinical features, laboratory determinants, and histopathological parameters in CKDu in Telangana, a state neighboring Andhra Pradesh, which has many CKDu hotspots. This study was done to document the clinical epidemiological risk profile and assess the kidney histology among CKDu patients in Telangana.

Materials and Methods

This is a single-center, prospective observational study conducted from March 2021 to November 2022 on CKD of undetermined origin patients presenting to Osmania General Hospital, Hyderabad. CKDu was defined as per the Indian consensus criteria.4

Inclusion criteria

Mandatory criteria: Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula and/or urine protein 1+ or more by dipstick.

Ultrasound showing small shrunken kidneys and/or kidney biopsy showing chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis with absence of immune deposits.

Exclusion criteria

Diabetes mellitus diagnosed by hemoglobin A1C (HbA1C) >6.5% and fasting blood sugar (FBS) >126 mg/dL or patient on antidiabetic medications; hypertension defined as blood pressure (BP) more than 140/90 in stages 1 and 2 CKD and BP >160/100 in stages 3, 4, and 5 CKD or patient requiring two or more types of antihypertensive medications for BP control. CKD due to any known cause (such as obstruction, stones, vasculitis, lupus); urine protein creatinine ratio >2 g/g; hematuria [>5 red blood cells/high power field (HPF)].

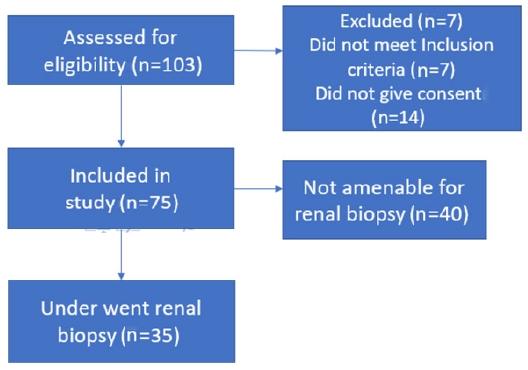

The study was approved by the Institute Ethical Committee. All subjects provided informed consent. The sociodemographics, clinical details, and investigations like complete hemogram, ultrasonography of kidneys, ureters, and urinary bladder (USG-KUB), and kidney function tests, including urine protein estimation, were recorded in a proforma. Renal functions were assessed at 0, 6, and 12 months.

Kidney biopsy was performed on those who gave consent, and the tissue was analyzed for light microscopic findings and immunofluorescence [Figure 1].

- Consort diagram.

Source of drinking water was noted. Surface water included water consumption from streams, lakes, and more, while groundwater was from borewells or municipal water. Drinking water was screened for toxins and heavy metals at the Institute of Preventive Medicine, Narayanaguda.

We analyzed the rate of GFR decline, the need for kidney replacement therapy, and mortality. Fast progressors were defined by a fall of eGFR of ≥4mL/min/1.73 m2 progression and slow progressors by a fall of eGFR of <4mL/min/1.73 m2 in a year. Analyses were carried out to identify the possible risk factors for faster progression of the disease, need for renal replacement therapy (RRT), and death.

Statistical methods

Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were carried out. Continuous measurements were presented on Mean ± SD (minimum-maximum). Categorical data was represented as frequencies and percentages. Significance was assessed at 5% level of significance. Chi-square test was used as test of significance for categorical data.

Unpaired t-test (for two groups) and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test (for more than two groups) were used as tests of significance for continuous data. P value <0.05 was considered significant. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 22.0 and R environment version 3.2.2 were used for the analysis of the data.

Results

Basic demographic profile and clinical characteristics are mentioned in Table 1. Fifty-two (69%) patients were non-oliguric at presentation; 21 (28%) had a history of nocturia; easy fatigability was seen in 58 (77.3%); and 30 (40%) had history of alternative medicine use for varied indications like infertility, hemorrhoids, joint pains. Edema was seen only in 10 (13.3%); 42.7% were from Hyderabad followed by 10% from Ranga Reddy district; hyperuricemia was seen in 33%; and 40% (n = 30) had CKD5 while 9.3% (n = 7) required RRT at presentation.

| Age | 41.72 ± 13.596 |

| Sex ratio (M:F) | 17:8 |

| Body mass index (cm/kg2) | 20.92 ± 3.628 |

| Education | 25.3%: uneducated (n = 19) |

| Agricultural background | 21.3% (n = 16) |

| Alcohol use | 37.3% (n = 28) |

| Tobacco use | 24% (n = 18) |

| Source of drinking water |

Groundwater: 77.3% (n = 58) Surface water: 22.7% (n = 17) |

| Alternate medicine intake in the preceding three years |

Leaf form: 43% (n = 13) Liquid form: 16% (n = 5) Powder: 30% (n = 9) Tablets: 10% (n = 3) |

| Comorbidities | Hypothyroid: 8% (n = 6) |

| History of excessive analgesic medicine use | 22.7% (n = 17) |

| Daily water intake (L) | 2.5 ± 1.1 |

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 9.47 ± 2.658 |

| Serum sodium (mEq/L) | 136.97 ± 1.074 |

| Serum potassium (mEq/L) | 4.37 ± 1.341 |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 8.60 ± 1.341 |

| Serum phosphate (mg/dL) | 4.66 ± 2.000 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 6.58 ± 2.488 |

| Serum bicarbonate (meq/L) | 17 ± 2.2 |

| Proteinuria (gm per day) | 1.2 |

A total of 26 patients progressed to ESKD. Of the 26 patients, 65.4% were males. A total of 23.1% patients in the agriculture sector reached end stage kidney disease (ESKD). About 80.8% of those patients who progressed to CKD5D had consumed groundwater, 42.3% had significant alcohol use, while 26.9% had history of smoking. The 53.8% patients who needed maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) had developed hypertension during the disease. All our patients recieved RRT in the form of HD only.

After excluding those who died or who needed MHD, it was found that a total of 28 patients had fast progression while 20 had slow progression of the CKD. Among the fast progressors, 75% were males, while 65% were males among the slow progressors (P=0.452). Among the fast progressors, 28.6% of patients had agricultural background and 42.9% patients had hypertension. The results of drinking water analysis are as outlined in Table 2.

| Water analysis | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | 84 | 2028 | 591.59 | 527.672 |

| pH | 7 | 8 | 7.50 | .512 |

| TDS | 55 | 1318 | 379.05 | 342.966 |

| Total hardness | 20 | 412 | 189.82 | 106.245 |

| Magnesium (mg/L) | 2 | 212 | 76.45 | 62.934 |

| Fluoride (mg/L) | 0 | 1 | .55 | .510 |

| Silica (mg/L) | 14 | 63 | 27.73 | 19.000 |

EC: Electrical conductivity, pH: Potential of hydrogen, TDS: Total dissolved solids

Among the 35 biopsies, all had histopathological features of chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) (>50%) was seen in 31.4% (N = 11), IFTA 25–50% in 45.7% (N = 16), and IFTA <25% was seen in 22.8% (N = 8). Serum creatinine correlated significantly with the IFTA (P 0.002) [Table 3]. Nineteen (54.3%) had >50% global glomerulosclerosis. The severity of global glomerulosclerosis correlated poorly with serum creatinine (P=0.616).

| IFTA | N | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| <25% | 8 | 2.2438 ± .61279 | 0.002 |

| 25–50% | 16 | 3.1800 ± 2.06941 | |

| >50% | 11 | 5.3027 ± 1.80014 | |

| Total | 35 | 3.6331 ± 2.09103 |

IFTA: Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy

Discussion

The main finding of the study is that patients with CKD who satisfy the CKDu phenotype as defined from the ‘hot spots’ are not uncommon elsewhere, and not limited to those with traditional risk factors such as agriculture. We document the existence of these cases in Telangana – this is the first report of its type.

Our study highlighted that CKDu may occur independently of agricultural exposure or exposure to heavy metals, impurities in drinking water, or use of tobacco or alcohol. Alternate medicine use may also be causal. As described in other reports, late presentation was common where the disease was asymptomatic and affected interstitial compartment. Though male sex and hypertension were associated with a faster progression, it was not statistically significant.

A slightly older age was reported by Ookalkar et al. from Maharashtra (40–70 years)5 and Parameswaran et al. reported a mean age of 52 years (tondaimanadalam nephropathy)6 [Table 4]. Male predominance was also reported by Parameswaran et al.6 with 75.2% males. Anand et al. from Sri Lanka reported that up to 40% patients had some formal education.7 In a study by Parameswaran et al., up to 50.9% of the study population did not have any form of formal education.6

| Study by | Parameswaran et al.6 | Tatapudi et al.1 | Anand et al.7 | Brooks et al.16 | González-Quiroz et al.17 | Our study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of study | Cross-sectional: community-based | Cross-sectional: community-based | Prospective | Retrospective observational | Meta-analysis | Prospective observational |

| Study region | Thondaimandalam: Tamil Nadu | Uddanam region: Andhra Pradesh | Sri lanka | Central America | Meso-America | Hyderabad - Telangana |

| Age | 40–50 years | 30–60 years | 40–50 years | 20-50 years | 30-50 years | |

| Gender | Male >female | Male >female | Male >female | Male>female | Male>female | Male>female |

| Occupation affected | Rice, paddy, and sugarcane farming and construction workers | Cashew nut, coconut, rice, and paddy farming | Rice, paddy, and chena farming | Sugar cane, cotton farming, fishing, mining | Sugar cane workers | Rice farming (only 21.3%) |

| Risk factor implicated | Low socioeconomic status, farm-related labor, advancing age, male sex | Male sex, increasing age, agricultural job | Chena farmers, family history of CKD, ayurvedic medicine use, cadmium exposure, pesticide use | Male sex, increasing age, sugar cane and banana farming, heavy metals exposure | Male sex, Family history of CKD, self medication with NSAIDs, Exposure to heavy metals, high humidity, heat stress | Male sex, Younger age, Herbal medicine intake (particularly leaves), NSAID use |

| Histological features | Not studied | Tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis | Chronic tubulointerstitial fibrosis | Chronic tubulointerstitial fibrosis | Not studied | Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis with interstitial inflammation and possible secondary glomerular changes |

CKD: Chronic kidney disease, NSAID: Non steroidal anti inflammatory drugs.

In other studies, the majority of patients with CKDu were agricultural workers—84% (Sri Lanka),8 53.6% (Puducherry), and 65.4% (Uddanam study).1 A systematic review found that sugarcane workers were more involved than paddy cultivation. Our study results indicate that people involved in other occupations are also at risk for the development of CKDu.

In our study, tobacco and alcohol use was higher than that in the study by Parameswaran et al.6 In contrast to our study, the use of alternative medicines was significantly lower in a study from Sri Lanka (1.2–3% used ayurvedic medicines).8 In a systemic review, multiple risk factors like dehydration, substance use, water sources, farming, dietary pattern, and history of leptospiral infection were proposed.9 Our study showed that alternative medicine use may be causal and should be explored further.

In the Parameswaran et al.6 study, hypertension was present in 53.9%. Alhough hypertension is an exclusion criterion in most definitions of CKDu, those with hypertension, especially those with less severe grade, showed interstitial disease in biopsies and no changes of hypertensive nephrosclerosis. Thus, mild hypertension/short duration hypertension should not be an exclusion criterion for CKDu, and if feasible, biopsy should be done to establish etiology in such cases.

In contrast to our study which showed acceptable water quality, in Sri Lanka increased hardness and electric conductivity of water are thought to be associated with CKDu. In a Sri Lankan study, surface water was the major source of drinking water.10 Surface water is found above the ground in streams and lakes and groundwater is underground that can be accessed from wells. Surface water can contain high amounts of contaminants and chemical pollutants while groundwater is relatively cleaner.10 Total hardness of drinking water was higher in a study from Sri Lanka,10 while in another study from the same region the hardness was 16.6–162 mg/L and the electrical conductivity was 35–2890 μΩ/cm.11 Liyanage et al. from Sri Lanka reported a higher fluoride level (0.28–6.8 mg/L) versus controls (0.02–0.70 mg/L).11

We were able to do biopsies in a significant proportion of cases, and found chronic interstitial nephritis to be the most common histological lesion. In El Salvador and Egypt, this form of CKDu is known as chronic interstitial nephritis in agricultural communities (CINAC).12 Gowrishankar et al. reported similar findings in Uddanam nephropathy.13 In a study by Wijkström et al., among 16 patients, 31% had >50% global glomerulosclerosis and 94% had periglomerular fibrosis. Global glomerulosclerosis and periglomerular fibrosis indicate the chronicity but do not help in establishing the etiology. These changes also indicate glomerular ischemia that is often found in nephrosclerosis. Among those with faster progression, significant global glomerulosclerosis was seen in 47.4%; 89.5% of patients had either diffuse or patchy interstitial inflammation. The chronicity in CKDu biopsies indicates the relatively asymptomatic early phase of this disease.14-17

The traditional definition of CKDu excludes patients with hypertension and/or proteinuria >1 gm per day. In our study, even patients with mild hypertension and/or proteinuria up to 2 gm had chronic interstitial nephritis on biopsy without any changes of hypertensive nephrosclerosis or glomerular involvement. Thus, CKD in such cases cannot be explained by either hypertension or glomerular disease and can be classified as CKDu. The Indian consensus group on CKDu has also included patients with proteinuria up to 2 g/gm creatinine and those with mild hypertension. This needs to be validated in larger studies that include biopsy.

Our study has certain limitations — it is a single center study, where we have used an unconventional definition of CKDu based on the Indian paper, which may limit comparison with other studies. Some of these cases could be due to other causes that were missed because of late presentation. Biopsy could not be done in all, as many had small kidneys at presentation. Finally, the water analysis was done at one point only due to logistic difficulties in outsourcing it for analysis, especially from a government hospital.

Our study documents the presence of CKDu phenotype in Telangana, outside the well-known hotspots. Agricultural background isn’t a necessity for the development of CKDu. Kidney biopsies showing chronic interstitial nephritis emphasizes that primary pathology driving the disease process could be in the tubulointerstitial compartment, and hence specific histopathological pointers toward CKDu should be looked for in the future biopsies, including electron microscopy study, as emphasized in the new position statement from the International Society of Nephrology’s (ISN’s) consortium on CKDu.15 There is a need for long-term multicentric studies utilizing demographic data, biochemical parameters, proteomics, metabolomics, and genomics and biopsy studies to determine the exact cause of CKDu.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- High prevalence of CKD of unknown etiology in Uddanam, India. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;4:380-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in India: What do we know and where we need to go. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:2743-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease of undetermined etiology around the world. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2021;46:142-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology: case definition for india – A perspective. Indian J Nephrol. 2020;30:236-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical profile of chronic kidney disease of unknown origin in patients of Yavatmal district, Maharashtra, India. J Ren Endocrinol.. 2020;7:e01.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A newly recognized endemic region of CKD of undetermined etiology (CKDu) in South India – “Tondaimandalam nephropathy”. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:2066-73.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Prospective biopsy-based study of CKD of unknown etiology in Sri Lanka. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:224-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Regulation of herbal medicine use based on speculation? A case from Sri Lanka. J Tradit Complement Med. 2016;7:269-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for endemic chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Sri lanka: Retrospect of water security in the dry zone. Sci Total Environ. 2021;795:148839.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Significance of mg-hardness and fluoride in drinking water on chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Monaragala, Sri Lanka. Environ Res. 2022;203:111779.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Significance of Mg-hardness and fluoride in drinking water on chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Monaragala, Sri Lanka. Environ Res. 2022;203:111779.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic Interstitial Nephritis in Agricultural Communities (CINAC). 2022.

- Pathology of Uddanam endemic nephropathy. Indian J Nephrol. 2020;30:253-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Renal morphology, clinical findings, and progression rate in Mesoamerican nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69:626-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidney biopsies among persons living in hotspots of CKDu: A position statement from the International Society of Nephrology’s Consortium of Collaborators on CKDu. Kidney Int. 2024;105:464-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CKD in Central America: A hot issue. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59:481-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- What do epidemiological studies tell us about chronic kidney disease of undetermined cause in Meso-America? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Kidney J. 2018;11:496-506.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]