Translate this page into:

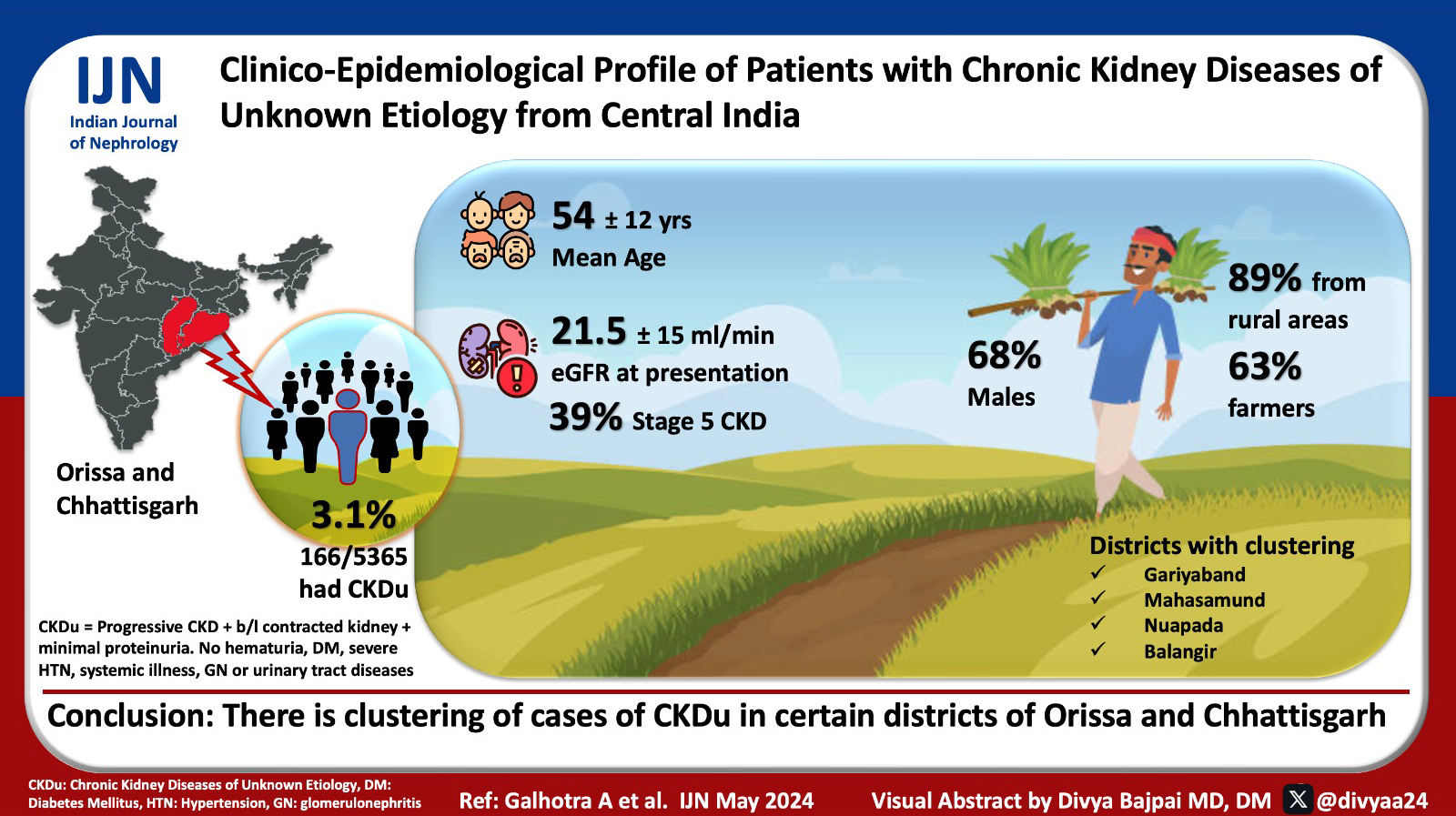

Clinico-Epidemiological Profile of Patients with Chronic Kidney Diseases of Unknown Etiology: A Hospital-Based, Cross-Sectional Study from Central India

Corresponding author: Dr. Vinay Rathore, Assistant Professor, Department of Nephrology, AIIMS, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. E-mail: vinayrathoremd@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Galhotra A, Rathore V, Pal R, Nayak S, Ramasamy S, Patel S, et al. Clinico-Epidemiological Profile of Patients with Chronic Kidney Diseases of Unknown Etiology: A Hospital-Based, Cross-Sectional Study from Central India. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:241–5. doi: 10.4103/ijn.ijn_68_23

Abstract

Background:

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) not associated with known risk factors, called CKD of unknown etiology (CKDu), has been reported from several geographically distinct regions across the world. This study reports the clinical and epidemiological profile of patients with CKDu from a new hotspot in central India.

Materials and Methods:

This cross-sectional study describes the sociodemographic, clinical, and laboratory profile of the patients diagnosed with CKDu visiting a tertiary care public hospital in the state of Chhattisgarh in central India between June 2019 and June 2021. CKDu was diagnosed as progressive CKD, minimal proteinuria, absence of hematuria, diabetes, severe hypertension, systemic illness, glomerulonephritis or other urinary tract diseases, and presence of symmetrically contracted kidneyon ultrasound.

Results:

A total of 166 (3.1%) out of 5365 patients with CKD were diagnosed with CKDu. The mean age was 53.6 ± 11.8 years. The patients were predominantly male (n = 113, 68.1%), belonged to rural areas (n = 147, 88.6%), and were engaged in farming (n = 105, 63.3%). The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at presentation was 21.5 ± 15.1 ml/min/1.73m2. Forty-four (26.5%) had stage 3 CKD, 57 (34.3%) had stage 4 CKD, and 65 (39.2%) had stage5 CKD. There was an over-representation of CKDu cases in patients with CKD from Gariyaband (36.0%) and Mahasamund (25%) districts of Chhattisgarh and Nuapada (35.0%) and Balangir (30.0%) districts of Odisha.

Conclusion:

The study suggests clustering of cases of CKDu in certain districts of Orissa and Chhattisgarh.

Keywords

Central India

Chhattisgarh

chronic kidney disease of unknown origin

CKDu

Orissa

Supebeda

Introduction

In the past two decades, several reports have documented clusters of people developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the absence of any known CKD risk factors from several geographically distinct, predominantly rural locations in diverse regions across the world.1 The disease has been called CKD of unknown origin (CKDu), and vigorous research is underway to understand its cause or causes, susceptibility factors, and approaches to mitigate the disease burden and its adverse health and societal consequences.

CKDu was first reported in India from the coastal Uddanam region of Andhra Pradesh and received the eponym Uddanam nephropathy, but it is now being reported from other geographiesas well.2 One such region is in and around Supebeda village of Deobhog block in northwest Chhattisgarh. According to media reports, 130 people have died of CKD in this village that has a population of 1800.3 A recent case series describing 12 patients of CKD from Supebeda reported that the characteristic of the disease is consistent with CKDu phenotype.4

A recent consensus conference in India called for studies to define the extent of existing as well as new geographic areas with high CKDu prevalence in India.5 This study reports the clinical–epidemiological profile of patients diagnosed with CKDu presenting toa tertiary care center in central India.

Materials and Methods

The study reviewed data of adult patients presenting with CKD to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Raipur, Chhattisgarh, between June 2019 and June 2021. Besides Chhattisgarh state, this center also serves as areferral center for patients from parts of the contiguous states of Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Maharashtra, and Jharkhand.

The diagnosis of CKDu was made inpatients who presented with CKD (defined as at least two estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] values of <60 ml/min/1.73m2 measured at least 3 months apart), absent or subnephrotic proteinuria, absence of hematuria, diabetes, severe arterial hypertension (blood pressure <160/100 mmHg in untreated patients or <140/90 mmHg in patients receiving up to two antihypertensive drugs), any systemic illness, glomerulonephritis, or other urinary tract diseases.5-7 Patients were required to have symmetrically contracted kidneys on ultrasound. A kidney biopsy was done in those with normal-sized kidneys.

Data were collected both retrospectively (June–September 2019) and prospectively (from October 2019 to May 2021) after obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (AIIMSRPR/IEC/2019/371). Sociodemographic, occupational, clinical, and laboratory data were obtained by interviewing the patients and/or were extracted from their medical records; the data were recorded in a proforma. The eGFR was calculated using Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration-CKD-EPI 2009 equation for non-blacks.8

Results

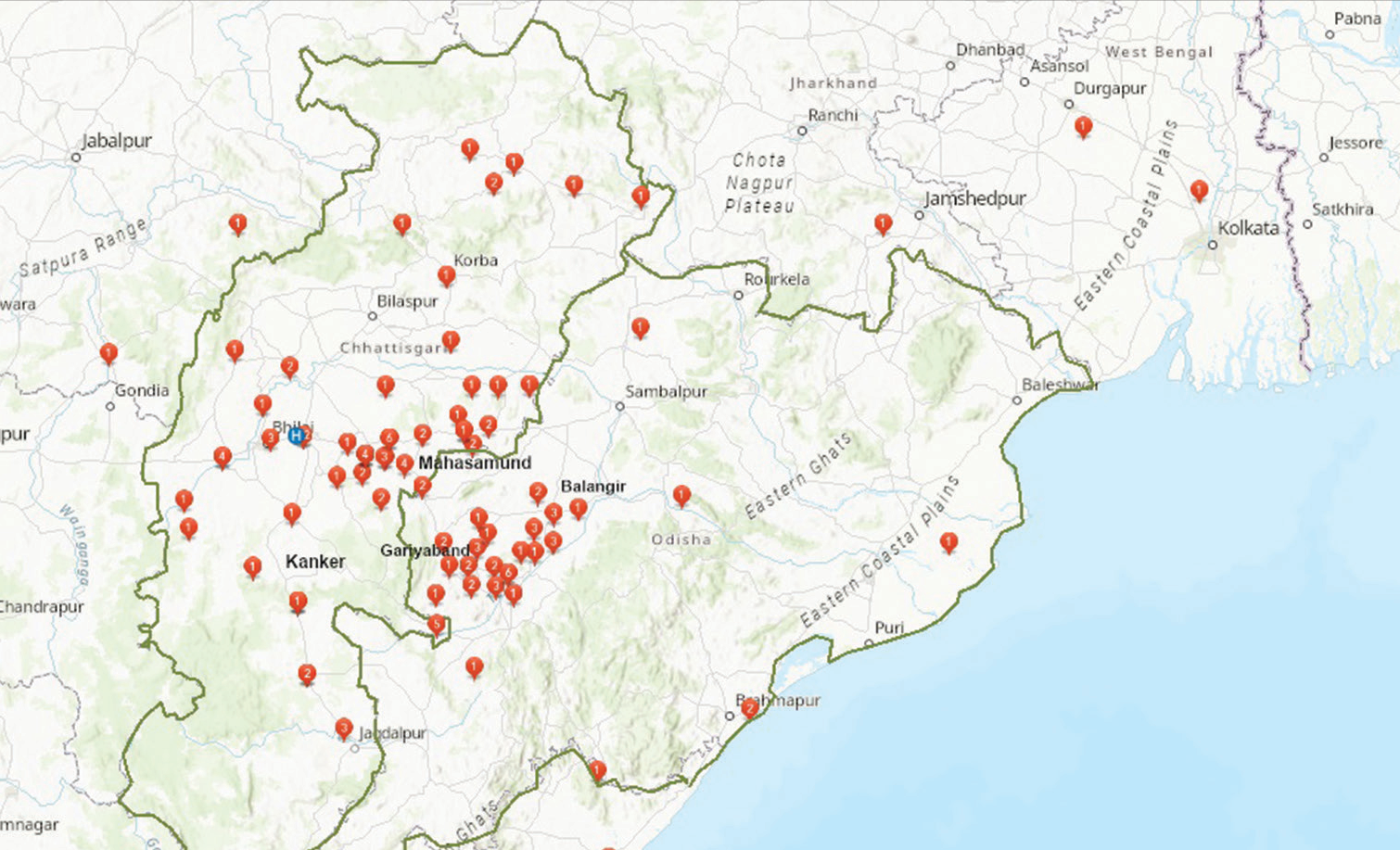

A total of 166 (3.1%) out of 5365 patients with CKD visiting AIIMS, Raipur, during the study period were diagnosed to have CKDu. The mean age of these patients was 53.6±11.8 years. The patients were predominantly male (n = 113, 68.1%) and belonged to rural areas (n = 147, 88.6%).Most of the patients belonged to four districts: 39 (23.5%) to Mahasamund district of Chhattisgarh, 37 (22.3%) to Balangir district of Odisha, 17 (10.2%) to Raipur district of Chhattisgarh, and 10 (6.0%) to Gariyaband district of Chhattisgarh [Table 1 and Figure 1]. Thirty-six percent (n = 10) of CKD patients visiting AIIMS, Raipur, from Gariyaband, 35.3% (n = 6) from Nuapada, 29.8% (n = 37) from Balangir, and 26.7% (n = 39) from Mahasamund had CKDu as a cause of CKD [Table 1 and Figure 1].

| State and district | CKD (n=5365) | CKDu (n=166, 3.1%) |

|---|---|---|

| Chhattisgarh | 4811 | 108 (2.4%) |

| Raipur | 2474 | 17 (0.7%) |

| Durg | 888 | 6 (0.7%) |

| Rajnandgaon | 117 | 6 (5.1%) |

| Mahasamund | 158 | 39 (25.0%) |

| Balodabazar | 167 | 1 (0.6%) |

| Bilaspur | 146 | 0 |

| Gariyaband | 28 | 10 (36%) |

| Kanker | 86 | 3 (3.5%) |

| Balod | 25 | 1 (4%) |

| Bemetara | 23 | 1 (4.3%) |

| Others | 699 | 23 (3.3%) |

| Orissa | 260 | 50 (21.9%) |

| Balangir | 138 | 37 (30.0%) |

| Nuapada | 17 | 6 (35.0%) |

| Kalahandi | 51 | 6 (12.0%) |

| Others | 54 | 4 (7.4%) |

| Madhya Pradesh | ||

| Anuppur | 26 | 0 |

| Shahdol | 41 | 0 |

| Rewa | 21 | 0 |

| Balaghat | 44 | 1 (2.3%) |

| Others | 39 | 1 (2.6%) |

| Other states (Jharkhand, Delhi, Gujarat, West Bengal, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Andhra Pradesh, Manipur, Maharashtra, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh) | 123 | 4 (3.3%) |

| Total | 5365 | 166 (3.1%) |

AIIMS=All India Institute of Medical Sciences, CKD=chronic kidney disease, CKDu=chronic kidney disease of unknown origin

- Geo-localization of CKDu patients visiting AIIMS, Raipur. CKDu = chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology.

A majority of the patients were engaged in farming (n = 105, 63.3%), unskilled physical labor (n = 20, 12.0%), or were homemakers (n = 20, 12.0%). Seventy-eight (74.2%) farm workers regularly used fertilizers and pesticides without personal protective equipment (PPE). The majority came from families with amonthly income below Rs. 10,000/- (n = 136, 81.9%), and nearly 50% were uneducated [Table 2]. The major source of drinking water was a borewell (n = 116, 69.9%), followed by an open well (n = 23, 13.9%).

| Sociodemographic characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.63±11.76 |

| 21–30 | 7 (4.2) |

| 31–40 | 17 (10.2) |

| 41–50 | 37 (22.3) |

| 51–60 | 62 (37.3) |

| >60 | 43 (25.9) |

| Male | 113 (68.1) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 77 (46.4) |

| Primary/secondary | 58 (34.9) |

| Higher secondary school | 21 (12.7) |

| Graduate andabove | 10 (6.0) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 10 (6.0) |

| Farmer | 105 (63.3) |

| Homemaker | 20 (12.0) |

| Clerk | 2 (1.2) |

| Laborer | 20 (12.0) |

| Shopkeeper | 5 (3.0) |

| Teacher | 4 (2.4) |

| Monthly family income (INR) | |

| <3000 | 42 (25.3) |

| 3001–10,000 | 94 (56.6) |

| 10,001–20,000 | 17 (10.2) |

| Don’t know | 13 (7.8) |

| Water source | |

| Hand pump | 12 (7.2) |

| Open water source | 23 (13.9) |

| Tap water | 15 (9.0) |

| Tubewell/borewell | 116 (69.9) |

| Exposed to pesticide, weedicides/fertilizer | 90 (53.6) |

| Personal protective equipment use in agriculture | 12 (7.2) |

| Substance abuse | |

| Smoking | 50 (30.1) |

| Tobacco | 88 (53.0) |

| Alcohol | 33 (30.0) |

AIIMS=All India Institute of Medical Sciences, CKDu=chronic kidney disease of unknown origin

Table 3 shows the clinical features of these patients. Common symptoms included decreased appetite (42.8%), weakness (40.4%), and pedal edema (39.9%). Sixty-nine (41.6%) patients regularly used over-the-counter analgesics, 51 (30.7%) patients used Ayurvedic medications, and 10 (6%) used herbal medication [Table 3].

| Clinical and laboratory characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Decreased appetite | 71 (42.8%) |

| Weakness | 67 (40.4%) |

| Pedal edema | 58 (39.9%) |

| Vomiting | 39 (23.5%) |

| Joint pain | 36 (21.7%) |

| Back pain | 30 (18.1%) |

| Over-the-counter analgesics use | 69 (41.6%) |

| Ayurvedic medication use | 51 (30.7%) |

| Herbal medication use | 10 (6.0%) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean±SD | 19.97±3.46 |

| ≥18.5 | 55 (33.1%) |

| ≥18.5–24.9 | 99 (59.6%) |

| ≥25 | 12 (7.2%) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean±SD | 121.86±12.97 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean±SD | 76.05±9.78 |

| No. of patients on antihypertensive medications at enrollment | 45 (27.1%) |

| Glycosylatedhemoglobin (%), mean±SD | 4.98±0.60 |

| Fasting blood sugar (mg/dl), mean±SD | 94.54±14.14 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl), mean±SD | 7.81±2.82 |

| Serum creatinine at enrollment (mg/dl), mean±SD | 5.10±4.32 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) at enrollment, mean±SD | 21.55±15.11 |

| CKD stage 3 | 44 (26.5%) |

| CKD stage 4 | 57 (34.3% |

| CKD stage 5 | 65 (39.2%) |

| Urine protein excretion (mg/day), mean±SD | 701.0±294.6 |

| Serum sodium (mmol/l), mean±SD | 135.51±6.62 |

| <120 mmol/l | 5 (3%) |

| 120–130 mmol/l | 25 (15.6%) |

| 130–135 mmol/l | 31 (18.7%) |

| >135 mmol/l | 105 (63.2%) |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L), mean±SD | 5.13±4.28 |

| <3.5 mmol/l | 20 (12.0%) |

| 3.5–5 mmol/l | 112 (67.5%) |

| >5.5 mmol/l | 34 (20.5%) |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dl), mean±SD | 7.70±2.35 |

| <7 mg/dl | 60 (36.1%) |

| 7–10 mg/dl | 83 (50.0%) |

| >10 mg/dl | 23 (13.9%) |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl), mean±SD | 8.74±1.21 |

| Serum phosphorous (mmol/l), mean±SD | 4.70±1.87 |

| Serum protein (g/dl), mean±SD | 6.59±0.97 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl), mean±SD | 3.65±0.64 |

| AST (U/l), mean±SD | 31.48±35.91 |

| ALT (U/l), mean±SD | 26.24±31.22 |

| Alkaline phosphate (U/l), mean±SD | 147.96±106.61 |

ALT=alanine aminotransferase, AST=aspartate aminotransferase, BMI=body mass index, CKD=chronic kidney disease, CKDu=chronic kidney disease of unknown origin, eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate, SD=standard deviation

The mean eGFR at presentation was 21.5 ± 15.1 ml/min/1.73m2. Forty-four (26.5%) had stage 3 CKD, 57 (34.3%) had stage 4 CKD, and 65 (39.2%) had stage 5 CKD. A total of 54 (30%) required renal replacement therapy. Also, 160 (96.4%) patients presented with contracted kidneys. Sixty-one (36.7%) patients had hyponatremia (defined as serum sodium <135mmol/l), while 78 (47.0%) patients had hyperuricemia (defined as serum uric acid >7.7 mg/dl).All tested negative for hepatitis B and hepatitis C. The mean urine protein exertion was 700.0 ± 294.6 mg/day [Table 3].

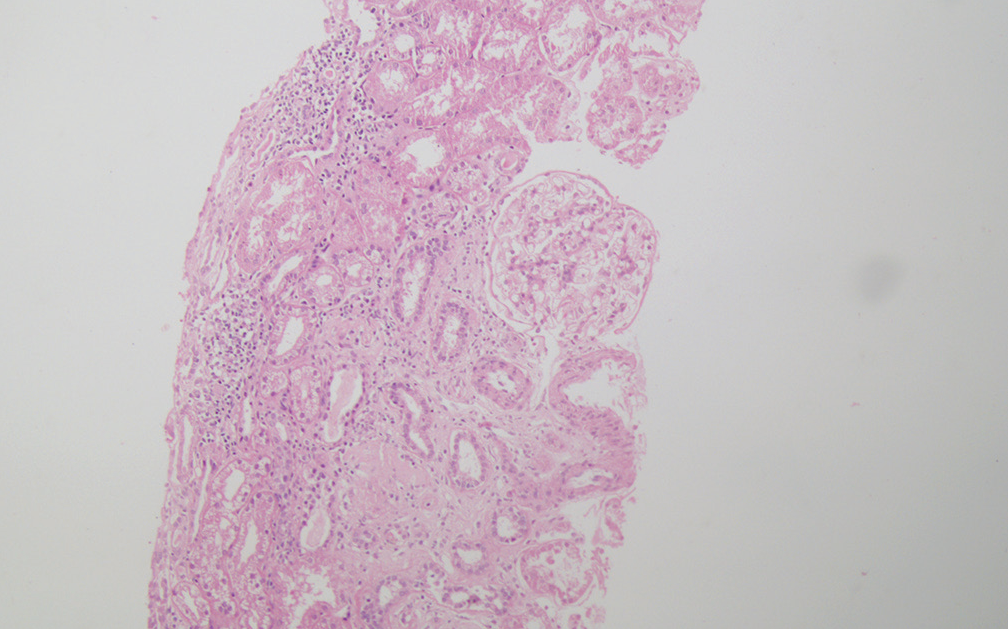

A kidney biopsy was performed on six patients. All of them showed chronic interstitial nephritis and periglomerular fibrosis. There was no immune deposition [Figure 2].

- Photomicrograph of renal biopsy of a 39-year-old male showing focal global glomerular sclerosis, mildly enlarged viable glomerulus with no proliferative activity, and focal chronic interstitial nephritis (H and E ×100). H and E = hematoxylin and eosin.

Discussion

Our study identifies new geographic areas with a relatively high burden of the CKDu phenotype in central India. Our report adds to the growing literature on the possibly unrecognized burden of CKDu in rural India. These findings build upon our initial report of CKDu in one village, which has received attention in the local press. However, this hospital-based study suggests that the geographic extent of the disease may be more extensive than previously recognized. Of note, evaluation of referral pattern suggests that the disease is overrepresented in Gariyaband (36.0%) and Mahasamund (25%) districts of Chhattisgarh and Nuapada (35.0%) and Balangir (30.0%) districts of Orissa.

Consistent with the global literature, most patients had nonspecific symptoms and presented late, with a large proportion needing immediate kidney replacement therapy. Majority of our patients were from a rural background and were involved in outdoor farm work or manual labor. Unlike CKDu from Latin American countries,5,9,10 our patients were older, which is consistent with other reports of CKDu from India.

Many patients in our study had hyponatremia and hyperuricemia. Hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hyperuricemia have been reported from other studies of CKDu and might be reflective of predominant involvement of the tubulointerstitial compartment.9,11,12 However, the mechanism and impact of this electrolyte imbalance are not well understood. Drugs targeting uric acid levels, like allopurinol, showed protection of kidney function in the animal model when exposed to heat stress, laying the groundwork for potential clinical trials.13

Prolonged and repeated dehydration, heat stress, heavy metal toxicity, pesticide and agrochemical exposure, contamination of drinking water, unknown infections, and genetics have been hypothesized to cause CKDu.14,15 Most of our patients were farmers or laborers, which demands strenuous work predisposing them to repeated dehydration. Further, the climate of this region is hot and humid most of the year. Most of the farm workers frequently used pesticides and fertilizers without PPE, potentially exposing them to chronic exposure.

Many of our patients also used over-the-counter analgesics and Ayurvedic and herbal medications to get relief from myalgia and back aches, which are common following strenuous physical activity required in agriculture and labor. These may have a role in the causation or progression of the disease.

The major limitation of our study is its hospital-based nature and therefore its susceptibility to referral bias. Further, the study period coincided with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic, which might have altered health-seeking behavior, potentially preventing patients with relatively paucisymptomatic earlier stages of the disease from seeking care. However, our study does point out toward clustering of cases of CKDu, which needs follow-up community-based studies.

Conclusion

To conclude, the study suggests clustering of cases of CKDu in certain districts of Orissa and Chhattisgarh. Further population-based studies are needed to confirm our findings and identify the geographic hotspots of CKDu in central India.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Snehlata Gahalawat, School of Public Health, AIIMS, Raipur, India, for her help in the preparation of the manuscript.

Statements and declarations

VJ has received grant funding from GSK, Baxter Healthcare, and Biocon and honoraria from NephroPlus and Zydus Cadilla, under the policy of all honoraria being paid to the organization. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was funded by intramural grants from AIIMS, Raipur.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Endemic nephropathy around the world. Kidney Int Rep. 2017;2:282-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddanam nephropathy/regional nephropathy in India: Preliminary findings and a plea for further research. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:344-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- One Chhattisgarh village has 130 kidney disease deaths in 15 yrs. No one knows thecause. 2021. The Print. Available from: https://theprint.in/india/one-chhattisgarh-village-has-30-kidney-disease-deaths-in-15-yrs-no-one-knows-the-cau se/629393/ [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 04]

- [Google Scholar]

- CKD of unknown origin in Supebeda, Chhattisgarh, India. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;6:210-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology: Case definition for India-A perspective. Indian J Nephrol. 2020;30:236-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology-Unit Weekly epidimiological report Vol: 36 No: 49; Research programme for chronic kidney disease of unknown aetiology in Sri Lanka Colombo: Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition; 2009. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10773525.2016.1203097

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in Sri Lanka. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2016;22:259-64.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of mesoamerican nephropathy in a kidney failure hotspot in nicaragua. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68:716-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics of chronic kidney disease of nontraditional causes in Salvadoran farming communities. MEDICC Rev. 2014;16:39-48.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renal morphology, clinical findings, and progression rate in Mesoamerican nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69:626-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics of chronic kidney disease of non-traditional causes in women of agricultural communities in El Salvador. Clin Nephrol. 2015;83(7 Suppl 1):56-63.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive primary health care and non-communicable diseases management: A case study of El Salvador. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19:50. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-1140-x

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CKD of uncertain etiology: A systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:379-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease of unknown etiology in India: What do we know and where we need to go. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:2743-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]