Translate this page into:

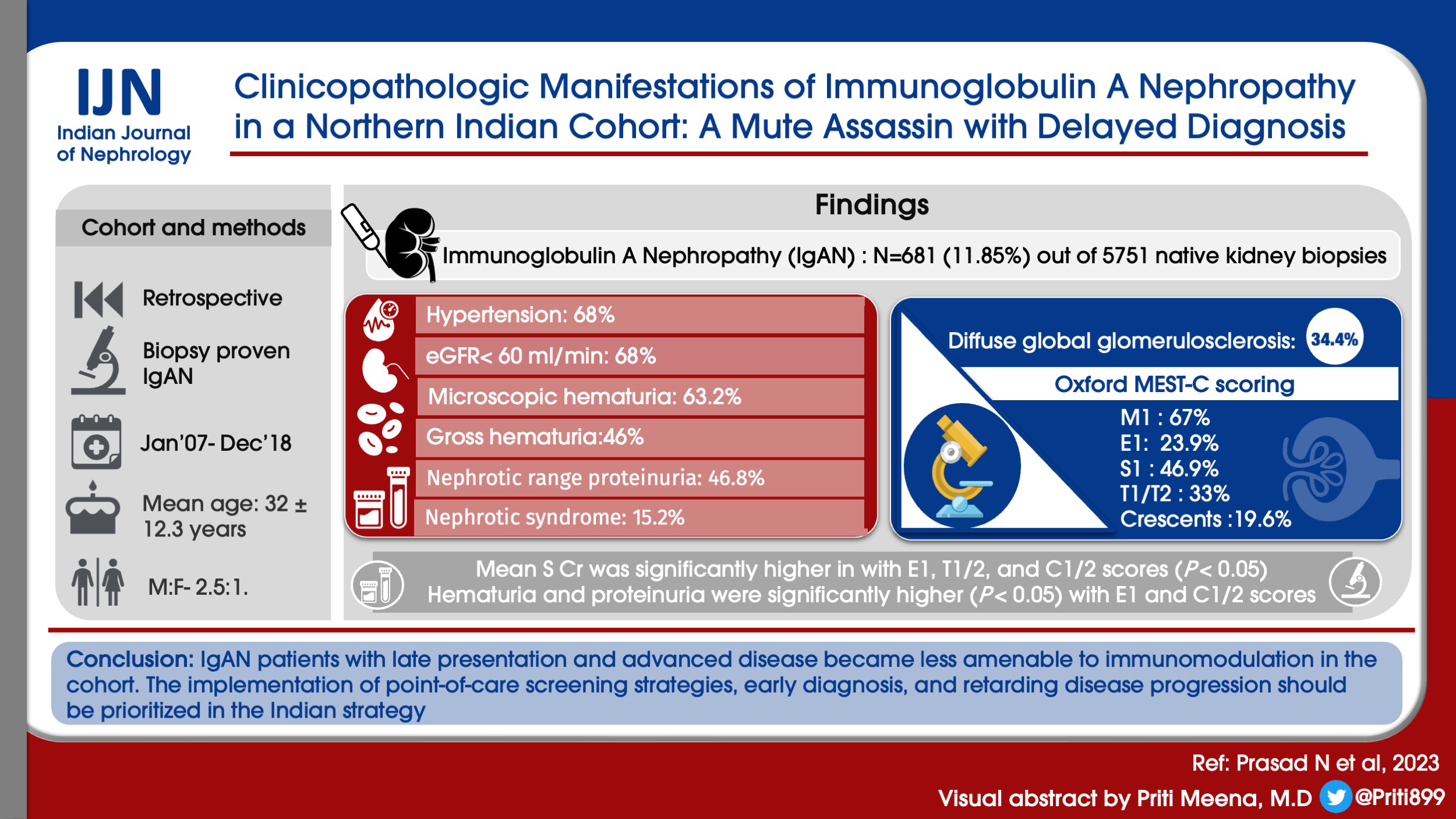

Clinicopathologic Manifestations of Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy in a Northern Indian Cohort: A Mute Assassin with Delayed Diagnosis

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common glomerulonephritis worldwide, but there is a marked geographic difference in its prevalence and prognosis. IgAN is known to have an aggressive course in Asians. However, its exact prevalence and clinicopathologic spectrum in North India are not well documented.

Materials and Methods:

The study included all patients aged above 12 years with primary IgAN on kidney biopsy from January 2007 to December 2018. Clinical and pathological parameters were noted. Two histopathologists independently reviewed all kidney biopsies, and MEST-C score was assigned as per the Oxford classification.

Results:

IgAN was diagnosed in 681 (11.85%) out of 5751 native kidney biopsies. The mean age was 32 ± 12.3 years, and the male to female ratio was 2.5:1. At presentation, 69.8% had hypertension, 68% had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of less than 60 ml/min, 63.2% had microscopic hematuria, and 4.6% had gross hematuria. The mean proteinuria was 3.61 ± 2.26 g/day, with 46.8% showing nephrotic range proteinuria and 15.2% showing nephrotic syndrome manifestation. Histopathologically, 34.4% of patients had diffuse global glomerulosclerosis. Oxford MEST-C scoring revealed M1 in 67%, E1 in 23.9%, S1 in 46.9%, T1/T2 in 33%, and crescents in 19.6% of biopsies. The mean serum creatinine was significantly higher in cases with E1, T1/2, and C1/2 scores (P < 0.05). Hematuria and proteinuria were significantly higher (P < 0.05) with E1 and C1/2 scores. Coexisting C3 was associated with higher serum creatinine at presentation (P < 0.05).

Conclusion:

IgAN patients with late presentation and advanced disease became less amenable to immunomodulation in our cohort. The implementation of point-of-care screening strategies, early diagnosis, and retarding disease progression should be prioritized in the Indian strategy.

Keywords

Glomerulonephritis

histological changes

IgA nephropathy

MEST classification

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerular disease worldwide.[1] The presentation of IgAN is varied, with symptoms ranging from microscopic to macroscopic hematuria; varying degrees of proteinuria, including nephrotic syndrome; hypertension; and kidney failure in the form of chronic kidney disease (CKD) as well as acute kidney injury (AKI).[2] The condition is also enigmatic in that in a proportion of patients, the course is benign, with intermittent hematuria episodes, and in others, it may present for the first time with crescentic glomerulonephritis and advanced kidney failure. There are also cases between these extremes, and the disease has a variable outcome across populations.[1,2] There is a marked geographic difference in the incidence of IgAN; incidence is modest in the USA (10%–20% of primary glomerulonephritis), higher in some European countries (20%–30%), and highest in developed countries like Japan, Singapore, and Hong Kong in Asia (40%–50%).[2] The frequency of IgAN varies not only from country to country, but also in different regions within countries. This sizeable geographic variability may arise due to differences in policies and threshold for kidney biopsies, early referral, and the variations in access to primary care, particularly in developing countries.[2]

In some Asian countries (namely, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan), urine screening tests are conducted in schools, while in some eastern and western countries, routine urinalyses are performed for military service and/or ahead of employment, which explains the apparent high incidence of IgAN in these regions.[3,4] In addition, indications for kidney biopsy strongly influence the reported incidence of IgAN.[5] Thus, the increased frequency of IgAN seen in some countries is due, at least in part, to a greater willingness of nephrologists to biopsy individuals with normal serum creatinine concentrations or estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) with persistent microscopic hematuria and/or proteinuria. A study showed that 43% of such individuals had IgAN.[6] Other factors that may influence the difference in reported IgAN incidence include socioeconomic status,[7] ancestry, and genetic background,[8,9] age,[10] and gender.[11] Of these, the socioeconomic status of the population strongly impacts health-care access and provision.[7] In developing countries like India, individuals with an asymptomatic persistent urinary abnormality are not referred to a specialist. As a result, IgAN is commonly not diagnosed early and presents much later in its natural history than in countries that offer/act on asymptomatic urine analysis screening.[7]

The prognosis of IgAN equally shows significant geographic and ethnic variation.[12] IgAN is considered to be a severe disease with poor outcomes in most Indian studies.[13-17] The Oxford classification of IgAN[18,19] developed in 2009 provides a histopathologic grading system based on five variables: (1) mesangial hypercellularity (M), (2) endocapillary hypercellularity (E), (3) segmental glomerulosclerosis (S), (4) tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (T), and (5) crescents (C). It has been validated in different populations worldwide.[19-28] It has also been validated in children.[29] The prognostic significance of extra capillary hypercellularity with IgA deposits and crescents was also studied.[27,28] There is, however, a lack of specific data on the natural history of IgAN in Indian populations, where screening urine analysis is not mandatory, referrals to specialists are late, and patients are at increased risk of advanced kidney failure.

The present retrospective study was conducted in a tertiary care public sector teaching hospital in North India. Unlike corporate hospitals, a major proportion of patients visiting this hospital are of low socioeconomic status, and consequently may present late in the course of the disease because of a lack of awareness about their health. We describe the clinicopathologic presentation of IgAN at our center.

Materials and Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we analyzed all the native kidney biopsies of adolescents and adults that were performed at our institute between January 2007 and December 2018. The study had been approved by the institute’s ethics committee. Diagnosis of IgAN was made when immunofluorescence (IF) showed dominant or co-dominant deposits of IgA with at least moderate positivity (2+) for IgA. Case selection included patients with IgAN who fulfilled the following criteria: (1) adult patients (age >12 years), (2) availability of at least six glomeruli for evaluation (light microscopy and IF), and (3) no evidence of secondary causes of IgAN, such as liver disease or Henoch–Schonlein purpura.

Demographic, clinical, and pathological parameters of the study population were studied. Data on age, gender, blood pressure (BP), clinical syndrome at presentation (i.e., at the time of kidney biopsy), proteinuria (semi-quantitative, 24-h urine protein or urine protein–creatinine ratio where available), urine microscopy, serum creatinine, and serum albumin were obtained from the hospital electronic information system. Based on laboratory data and clinical presentation, patients were categorized into one of the following five syndromes: (1) nephrotic syndrome, (2) AKI and acute kidney disease (AKD), (3) macroscopic hematuria, (4) CKD, and (5) asymptomatic urinary abnormality (AUA), based on standard criteria. The eGFR was calculated by using Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation in adults and the Schwartz equation in adolescents.[30] Patients whose kidney biopsy showed diffuse global glomerulosclerosis (DGGS) and/or severe tubular atrophy were also classified as CKD. Hypertension was defined as systolic BP (SBP) of ≥140 mmHg and diastolic BP (DBP) of ≥90 mmHg in adults and SBP of ≥130 mmHg and DBP of ≥80 mmHg in adolescents.[31]

If a patient had a history of even a single episode of macroscopic hematuria, then the patient’s clinical presentation was labeled as macroscopic hematuria. Microscopic hematuria was defined as the presence of three red blood cells per high-power field in urine sediment under light microscopy. Patients who were asymptomatic and were detected to have microscopic hematuria and/or proteinuria were classified as AUA. Wherever possible, patients were classified into a single syndrome, but patients could be classified into more than one clinical syndrome.

Evaluation of kidney biopsies

Light microscopic evaluation of the kidney biopsy included evaluation of the total number of glomeruli, percentage of sclerosed glomeruli, vascular changes, and the degree of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. All histological analyses were performed independently by two kidney histopathologists. The Oxford MEST-C scoring for mesangial hypercellularity (M), endocapillary hypercellularity (E), segmental sclerosis (S), and tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (T) and crescents (C) was performed for all kidney biopsies with >8 glomeruli.[18] The biopsies were also staged according to the Haas classification. In all cases, seven-panel direct IF for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, kappa, and lambda light chain intensity and pattern of distribution were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and their distributions examined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Independent sample t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare normally distributed variables, while the Mann–Whitney test or the Wilcoxon test was used for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s Chi-square test. Bonferroni correction was performed when comparisons were made between multiple variables. All tests were two-sided, and significance was assessed at P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for Windows on a standard computer running Windows 10.

Results

We reviewed all the native kidney biopsies performed between January 2007 and December 2018. Out of 5751 native kidney biopsies, IgAN was diagnosed in 681 biopsies (11.8%). After excluding secondary cases and children less than 12 years of age, a total of 560 (9.7%) cases of primary IgAN were included in the study.

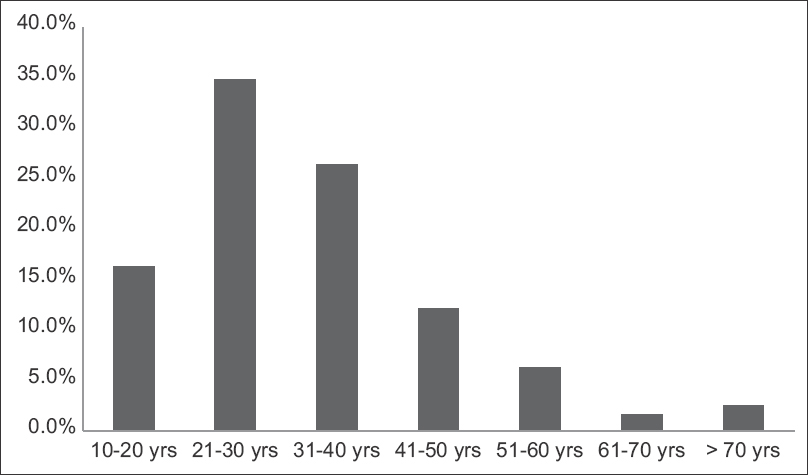

Clinical presentation

The clinical characteristics at presentation are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. The mean age was 32 years (range 12–75, peak incidence between 21 and 30 years) [Figure 1], with a distinct male preponderance (male: female ratio of 2.5:1). The majority of patients presented with an eGFR <60 ml/min (72.5%; n = 406), with a mean eGFR of 45.9 ± 37.3 ml/min/1.73 m2 and a mean serum creatinine of 3.0 ± 2.47 mg/dl. CKD was the most common clinical presentation seen in 307 (54.8%) of the patients. The mean 24-h proteinuria was 3.61 ± 2.26 g/day, and nephrotic range proteinuria was seen in 46.8% (n = 262). However, a clinical presentation with nephrotic syndrome was far less common and only seen in 85 (15.2%) patients. AKI was present in 8% of cases, with recurrent macroscopic hematuria present in 4.6% (n = 26) of cases and asymptomatic urinary abnormalities in 15% (n = 84) of cases. In all patients with AKD, rapidly progressive renal failure presentation was rare, accounting for 22 (3.92%) patients. Microscopic hematuria was common and was seen in 354 (63.2%) patients. Hypertension was defined as SBP/DBP ≥130/80 mmHg. Hypertension was common and seen in 391 (69.8%) with mean SBP of 141.3 ± 18.5 mmHg and mean DBP of 85.3 ± 11.3.

| Percentage (n) | Mean±SD | Median (range) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 32±12.3 | 30 (12-75) | |

| Males | 72.5% (406) | ||

| Hypertension | 69.8% (391) | ||

| SBP (mmHg) | 141.3±18.59 | 140 (100-120) | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 85.3±9.7 | 90 (40-150) | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 3.08±2.47 | 2.3 (0.5-17.5) | |

| eGFR (CKD-EPI) (ml/min) | 45.9±37.27 | 34.29 (3.25-160.4) | |

| eGFR less than 60 ml/min | 72.5% (406) | ||

| 24-h urine protein (g) | 3.61±2.26 | 3.24 (0.19-11.42) | |

| Microscopic hematuria (RBC >2/hpf) | 63.2% (354) | ||

| RBC/hpf | 18.5±32.5 | 8 (0-300) | |

| Proteinuria range | |||

| >3 g/day | 46.8% (262) | ||

| 1-3 g/day | 34.1% (191) | ||

| <1 g/day | 19.1% (107) | ||

| Syndromic presentation | |||

| Nephrotic syndrome | 15.2% (85) | ||

| AKI or AKD | 8% (45) | ||

| Recurrent macroscopic hematuria | 4.6% (26) | ||

| CKD | 54.8% (307) | ||

| ASU | 15.5% (87) | ||

| AKI/AKD with macroscopic hematuria | 0.3% (2) | ||

| Nephrotic syndrome with macroscopic hematuria | 0.5% (3) | ||

| CKD with macroscopic hematuria | 0.9% (5) |

AKD=acute kidney disease, AKI=acute kidney injury, ASU=asymptomatic urinary abnormality, CKD=chronic kidney disease, CKD-EPI=Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration, DBP=diastolic blood pressure, RBC=red blood cells, SBP=systolic blood pressure, SD=standard deviation

- Age distribution

Pathological features

The distribution of histopathologic scores for the cases (Haas classification and Oxford MEST-C score) is shown in Table 2. Diffuse global glomerulosclerosis (DGGS; more than 50% of the glomeruli showing global sclerosis) was seen in 34.4% (n = 193) of our cohort. Crescents were seen in 31.6% (177/560) of cases, of which 32.7% were active crescents (cellular or fibrocellular). Tubular atrophy was assessed in all samples semi-quantitatively on the basis of the percentage of affected cortical surface area. Mild tubular atrophy (10%–25%) was seen in 35.8%, moderate tubular atrophy (>25%–50%) in 38.2%, and severe tubular atrophy (>50%) in 14.5% cases. According to the Haas classification, the majority of cases had advanced disease with 219 (39.1%) showing class IV and 205 (35.6%) showing class V. Classes I, II, and III were observed in 6%, 9.1%, and 8.8% of cases, respectively.

| Number of affected biopsies (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Diffuse global glomerulosclerosis | 193/560 | 34.4 |

| Oxford classification | ||

| M | ||

| M0 | 112/339 | 33 |

| M1 | 227/339 | 67 |

| E | ||

| E0 | 258/339 | 66.1 |

| E1 | 81/339 | 23.9 |

| S | ||

| S0 | 180/339 | 53.1 |

| S1 | 159/339 | 46.9 |

| T | ||

| T0 | 227/339 | 67 |

| T1 | 96/339 | 28.3 |

| T2 | 16/339 | 4.7 |

| C | ||

| C0 | 230/339 | 67.8 |

| C1 | 60/339 | 10.7 |

| C2 | 49/339 | 8.8 |

| Haas staging | ||

| Class I | 34/560 | 6% |

| Class II | 52/560 | 9.1% |

| Class III | 50/560 | 8.8% |

| Class IV | 219/560 | 39.1% |

| Class V | 205/560 | 36.6% |

| TA | ||

| No TA | 64/560 | 11.4% |

| Mild TA (10%-25%) | 201/560 | 35.8% |

| Moderate TA (25%-50%) | 214/560 | 38.2% |

| Severe TA (>50%) | 81/560 | 14.5% |

| Immunofluorescence | ||

| IgA (3+or more) | 472/560 | 84.4% |

| IgM (2+or more) | 265/560 | 47.3% |

| C3 (2+or more) | 401/560 | 71.6% |

C=crescent, C3=complement 3, E=endocapillary hypercellularity, IgA=immunoglobulin A, IgM=immunoglobulin M, M=mesangial hypercellularity, S=segmental sclerosis, T=tubular atrophy, TA=tubular atrophy

A total of 339 cases were scored using the Oxford MEST-C classification system; 221 biopsies were excluded as they contained less than eight viable glomeruli or had extensive glomerulosclerosis (>50% globally sclerosed glomeruli). On MEST-C scoring, mesangial hypercellularity (M1) was seen in 67%, endocapillary hypercellularity (E1) in 23.9%, segmental glomerulosclerosis (S1) in 46.9%, tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (T1) in 28.3%, T2 in 4.7%, C1 in 10.7%, and C2 in 8.8% of cases. Semi-quantitative analysis of immunofluorescent staining revealed >2+ C3 deposition in 71.6% cases, >2+ IgM deposition in 47.3% cases, and moderate IgG deposition in 14.6% cases.

Relationship between clinical and pathological features at presentation

There was a significant correlation between the extent of proteinuria at presentation and the presence of endocapillary hypercellularity (E1) and crescents (C1/2) [Table 3]. Similarly, the amount of hematuria correlated with E1 and C1/2 lesions as well as the presence of segmental sclerosing lesions (S1). In parallel, E1 and C1/2 lesions also correlated with serum creatinine at the time of biopsy, as did the extent of tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (T1/2) and the intensity of glomerular C3 deposition.

| Oxford score | Creatinine | 24-h urine protein | RBC/hpf | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean±SD | P | Mean±SD | P | Mean±SD | P | |

| M score 0 | 2.37±2.13 | 0.82 | 3.20±1.92 | 0.09 | 17.8±39.3 | 0.83 |

| 1 | 2.32±1.79 | 3.95±2.63 | 18.6±31.5 | |||

| E score 0 | 2.09±1.67 | <0.001 | 3.54±2.38 | 0.03 | 15.3±29.1 | 0.004 |

| 1 | 3.14±2.36 | 4.20±2.57 | 28.01±46.0 | |||

| S score 0 | 2.35±1.98 | 0.92 | 3.65±2.55 | 0.70 | 22.5±42.1 | 0.014 |

| 1 | 2.33±1.83 | 3.76±2.32 | 13.7±21.4 | |||

| T score 0 | 1.95±1.69 | <0.001 | 3.58±2.3 | 0.24 | 15.7±32.4 | 0.107 |

| 1 | 2.92±1.89 | 4.06±2.7 | 24.4±38.6 | |||

| 2 | 4.42±2.62 | 3.37±1.08 | 20.3±28.8 | |||

| C score 0 | 2.08±1.7 | <0.001 | 3.28±2.17 | <0.001 | 13.0±23.2 | <0.001 |

| 1 | 2.06±1.43 | 4.83±2.7 | 23.0±37.6 | |||

| 2 | 4.21±2.23 | 4.2±2.64 | 37.8±58.3 | |||

| Immunofluorescence | ||||||

| C3 staining | ||||||

| Less than 2 | 2.30±1.98 | <0.001 | 3.61±2.29 | 0.97 | 16.8±34.2 | 0.43 |

| +2+ or more | 3.4±2.58 | 3.62±2.26 | 19.2±31.9 | |||

| IgM | ||||||

| Less than 2 | 3.17±2.42 | 0.37 | 3.54±2.27 | 0.39 | 18.2±33.1 | 0.81 |

| +2+ or more | 2.99±2.5 | 3.70±2.26 | 18.9±32.0 | |||

| IgG | ||||||

| Less than 2 | 3.14±2.70 | 0.19 | 3.58±2.28 | 0.37 | 17.4±31.3 | 0.08 |

| +2+ or more | 2.76±1.8 | 3.82±2.19 | 24.6±38.6 | |||

| IgA | ||||||

| Less than 3 | 2.8±2.18 | 0.23 | 3.37±2.2 | 0.29 | 24.1±31.3 | 0.06 |

| +3+ or more | 3.14±2.52 | 3.65±2.2 | 24.6±38.6 | |||

C=crescent, C3=complement 3, E=endocapillary hypercellularity, IgA=immunoglobulin A, IgG=immunoglobulin G, IgM=immunoglobulin M, M=mesangial hypercellularity, RBC=red blood cells, S=segmental sclerosis, SD=standard deviation, T=tubular atrophy

Clinicopathologic characteristics of IgAN according to the clinical syndrome at presentation

Patients who presented with the nephrotic syndrome had, as expected, lower serum albumin and higher serum cholesterol and triglycerides when compared to other groups [Table 4]. Kidney dysfunction was observed in 24%, microscopic hematuria in 55.8%, and hypertension in 30% of cases. Also, 67% of these cases had an M1 and 32% also had crescents on kidney biopsy.

| Nephrotic syndrome* (n=105) | Asymptomatic urinary abnormality (n=87) | Macroscopic hematuria* (n=16) | CKD (n=307)* | AKI/AKD (n=45) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 27.4±11.1 | 34.96±11.50 | 22.4±9.3 | 33.2±11.96 | 31.4±14.2 |

| Males (%) | 64.4% (n=68) | 63.1% (n=53) | 70.6% (n=12) | 76.9% (n=236) | 75% (n=33) |

| S. creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.30±1.1 | 1.16±0.33 | 1.76±1.16 | 4.07±2.54 | 4.52±4.16 |

| Renal dysfunction (eGFR <60 ml/min) | 29.8% (31) (n=25) | 29.9% (26) | 29.4% (n=5) | 98.7% (n=303) | 91.1% (41) |

| Microhematuria (%) | 55.8% (n=58) | 46.4% (n=39) | 32.3% (n=11) | 64.5% (n=198) | 97.7% (n=43) |

| Serum cholesterol (mg/dl) | 278.6±121 | 210±214 | 181±68.3 | 179±65 | 233±184 |

| Serum triglyceride (mg/dl) | 219.0±126 | 175±112 | 159±57.8 | 168±105 | 209±144 |

| S. albumin (g/l) | 2.82±0.19 | 4.0±0.54 | 3.72±0.64 | 3.5±0.6 | 3.0±0.52 |

| Hypertension (%) | 32.7% (n=32) | 50% (n=42) | 17.6% (n=3) | 91.9% (n=282) | 59.1% (n=26) |

| Global glomerulosclerosis (>50%) | 2.9% (n=3) | 7.1% (n=6) | 15.4% (n=4) | 57.3% (n=176) | 6.8% (n=3) |

| M score 1 | 62/93 (66.7%) | 44/74 (52.4%) | 11/18 (61%) | 86/115 (74.8%) | 27/41 (34%) |

| E score 1 | 23/93 (24.7%) | 9/74 (12.2%) | 3/18 (16.7%) | 24/112 (20.9%) | 22/41 (53.7%) |

| S score 1 | 40/93 (43%) | 30/74 (40.5%) | 8/18 (44.4%) | 68/115 (22.1%) | 14/41 (34.5%) |

| T score 1 | 16/93 (17.2%) | 9/74 (12.2%) | 3/18 (16.7%) | 56/115 (48.7%) | 15/41 (36.6%) |

| T score 2 | 0/93 (0%) | 0/74 (0%) | 0/18 (0%) | 15/115 (13%) | 1/41 (2.4%) |

| C score 1 | 27/93 (29%) | 7/74 (8.3%) | 2/18 (11.1%) | 23/115 (20%) | 2/41 (4.9%) |

| C score 2 | 3/93 (3.2%) | 0/74 (0%) | 3/18 (16.7%) | 15/115 (13%) | 29/41 (70.7%) |

| Proteinuria | |||||

| 1-3 g/day | 0% (n=0) | 53% (n=45) | 42.3% (n=11) | 38% (114) | 15/41 (34.9%) |

| More than 3 g | 100% (n=104) | 7.1% (n=6) | 23.1% (n=6) | 47% (141) | 21/41 (48.8%) |

AKD=acute kidney disease, AKI=acute kidney injury, C=crescent, CKD=chronic kidney disease, E=endocapillary hypercellularity, eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate, M=mesangial hypercellularity, S=segmental sclerosis, T=tubular atrophy. *At the time of analysis, patients with nephrotic syndrome and gross hematuria or CKD and gross hematuria or AKI/AKD with gross hematuria were classified as nephrotic syndrome, CKD, and AKI/AKD, respectively

As compared to CKD patients, patients with AKI had similar serum creatinine values; however, microscopic hematuria was observed in 97.7% of AKI and 64.5% of CKD patients. Hypertension was observed in 91.5% of CKD patients and 59.1% of AKI patients. AKI patients had higher triglycerides and cholesterol and lower serum albumin levels compared to those with CKD. M1 and T1/2 scores were more common in CKD patients, and E1, S1, and C1/2 scores were more common in those with AKI. DGGS was seen in 57.3% of CKD patients, and 33% of these cases had coexistent crescents on biopsy. Crescents were identified in 75.3% of cases of AKI, with 70% of cases having crescents in more than 25% of the sampled glomeruli (C score of 2).

The patients with macroscopic hematuria were younger (mean age 22.3 years), and 32% of cases had kidney dysfunction at the time of presentation. Hypertension was seen in 34.6% of cases, M1 in 61%, and crescents in 27.8% of cases. Patients presenting with an AUA had normal kidney function; however, there was evidence of significant disease activity with an M1 score in 52.4% of cases, with an S1 score in 40.5% of cases, and with a C1 score in 8.3% of cases. No case had a C2 score. Sub-nephrotic proteinuria was seen in 53% of patients.

Discussion

The geographic and ethnic variations in biopsy prevalence of IgAN are well known. Table 5 summarizes the clinical and pathological data reported in studies from other parts of the world, and Table 6 summarizes the published data from India. IgAN is relatively more common in Asia, especially in Japan, Singapore, and China.[12,32-35] In a worldwide survey of 42,000 biopsies, the prevalence of IgAN varied from 6.1% in Latin America to 11.8% in USA/Canada, 22.8% in Europe, and 39.5% in Asia.[32] Studies from East Asia report a biopsy prevalence as high as 50% in China,[28,33] 47.2% in Japan,[34] and 40% in Singapore.[35,36] A better primary health-care system may partly explain this high prevalence delivering an early diagnosis and more robust screening programs to identify the disease in these countries including India.[4,11,16,37,38] In the present study, we observed that the biopsy prevalence of IgAN was 11.85%, of which 9.7% had primary IgAN. Previous studies from India report a biopsy prevalence of 4.5%–16%.[13,16,17] A multicenter study from South India by Gowrishankar et al.[17] revealed a prevalence of 13.2%, which mainly included biopsy specimens from corporate sector hospitals of the southern part of India. The variation in reported prevalence in India is likely due to the varying health-care infrastructure and screening programs in different Indian states and differing biopsy thresholds, particularly for asymptomatic patients, and the availability of IF studies in different hospitals in India. Our institute is a tertiary care government health center that caters mainly to people of lower and middle socioeconomic status. One of the most important observations in our study was the high prevalence of diffuse glomerulosclerosis at the time of presentation, highlighting the late presentation of our patients to nephrologists.

| Author | Country | Year | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Hypertension (%) | Proteinuria (mean) | Gross hematuria (%) | Renal failure | M1 | E1 | S1 | T1 | T2 | C1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | ||||||||||||||

| Shi[38] | China | 2011 | 410 | 31 | NA | 1.7 g/day | 34 | 19% (CKD-III) | 56% | 57% | 75% | 14% | 8% | 60% |

| Katafuchi[19] | Japan | 1994 | 225 | 32 | 22 | 16% (>3 g/day) | 20 | 20% (CKD-III) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Katafuchi[39] | Japan | 2011 | 702 | 30 | NA | 0.9 (UPCR) | 20 | 30% | 12% | 42% | 79% | 18% | 12% | 63% |

| Kang[40] | Korea | 2012 | 197 | 32.4 | 24.4 | 2.07 g/day | 11.2 | NA | 74% | 11% | 56% | 26% | 8% | NA |

| Shima[29] | Japan | 2012 | 161 | 11.7 | NA | 0.7 g/day | 66 | NA | 64% | 58% | 8% | 1% | 0% | 52% |

| Zeng[22] | China | 2012 | 1026 | 34 | 33 | 1.3 g/day | 34 | 59% | 43% | 11% | 83% | 24% | 3% | 48% |

| Lee[24] | Korea | 2012 | 69 | 34 | NA | 1.2 g/day | 27 | 64% | 61% | 32% | 80% | 25% | 12% | NA |

| Le[25] | China | 2012 | 218 | 14 | 6.5 | 1.5% | 57 | NA | 45% | 23% | 62% | 7% | 1% | 56% |

| Kataoka[41] | Japan | 2011 | 43 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 81% | 53% | 81% | NA | NA | 53% |

| Moriyama[42] | Japan | 2012 | 42 | 34.2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 60% | 43% | 83% | 40% | 26% | NA |

| Yoon[43] | Korea | 2012 | 377 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 20% | 23% | 61% | 11% | 0% | NA |

| Zhang[28] | China | 2018 | 1152 | 35.4 | 33.1 | 1.42 g/day | NA | NA | 43% | 42% | 77% | 33% | 0% | 36% |

| Current study European | India | 2020 | 560 | 32 | 69.8 | 3.61 g/day | 4.6 | 68% | 67% | 24% | 47% | 28% | 5% | 20% |

| Edstrom[44] | Sweden | 2011 | 99 | 9.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 31% | 10% | 23% | 12% | 5% | 18% |

| Almartine[23] | France | 2011 | 183 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 21% | 14% | 54% | 20% | 10% | 5% |

| Coppo[26] | Europe | 2014 | 1147 | 36% | 65 | 1.3 g/day | NA | 37% (CKD-III or more) | 28% | 11% | 70% | 17% | 45 | 11% |

| Stefan[27] | Romania | 2016 | 121 | 40.1 | 58 | 2.0 g/day | NA | NA | 72% | 23% | 79% | 71% | NA | 31% |

| Elkarou[45] | France | 2011 | 128 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 34% | 25% | 69% | 26% | 23% | 24% |

| Gutirrez[46] | Spain | 2012 | 141 | 23.7 | NA | 0.2 g/day | 100 (MSH) | NA | 33% | 9% | 16% | 5% | 0% | NA |

| North America | ||||||||||||||

| Yau[47] | USA | 2011 | 54% | 41 | 48 | 72% (>1 g/day) | 24 | 31.1% | 72% | 20% | 81% | 13% | 22% | 19% |

| Multinational | ||||||||||||||

| Oxford[18] | Multi | 2009 | 265 | 30 | 31 | 1.7 g/day | NA | 64% (CKD-III or more) | 80.6% | 42% | NA | NA | NA | 45% |

| Barbour[48] | Multi | 2015 | 901 | 38.1 | NA | 1.5 g/day | NA | NA | 43% | 18% | 75% | 18% | 4% | 17% |

C=crescent, E=endocapillary hypercellularity, IgAN=IgA nephropathy, M=mesangial hypercellularity, S=segmental sclerosis, T=tubular atrophy, uPCR, urinary protein creatinine ratio

| Author | Year | Sample size | Mean age (years) | Hypertension (%) | Proteinuria (nephrotic) (%) | Gross hematuria (%) | Renal failure (%) | M1 | E1 | S1 | T1 | T2 | C1/2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhuyan[49] | 1992 | 83 | NA | 39 | 24 | NA | 34 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Muthukumar[50] | 2002 | 98 | 25.7 | 9.2 | 25.6 | 5.1 | 13.5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chacko[13] | 2005 | 478 | 32 | 58 | 55 | 16 | 60 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Chandrika[14] | 2007 | 227 | 30 | 35 | 36.7 | 18.9 | 5.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mittal[15] | 2012 | 66 | 29.9 | 78.8 | 23.1 | 81 (Microscopic) | NA | 79.6% | 29.6% | 57.4% | 74.2% (T1+T2) | NA | 56.6% |

| Bagchi[51] | 2012 | 103 | 28.8 | 39.4 | 63.1 | 91 (Microscopic) | 16.5 | 77.7% | 9.7% | 43.7% | 39.8% (T1+T2) | NA | 10.7% |

| Swarnlata[17] | 2019 | 3345 | 35.8 | 60.4 | 41.7 | 79.9 (Microscopic) | 78.9 | 59.3% | 38.8% | 60.3% | 20.5% | 4.2% | 29.9% |

| Alexander[52] | 2021 | 201 | 36 | 84.1 | 34 | 10 | 79.3 | 11.4% | 43.8% | 80% | 37.8% | 41.1% | 16% |

| Current study | 2020 | 560 | 32 | 69.8 | 46.8 | 4.9 | 68 | 67% | 23.9% | 46.9% | 28.3% | 4.7% | 19.5% |

C=crescent, CKD=chronic kidney disease, E=endocapillary hypercellularity, IgA=immunoglobulin A, M=mesangial hypercellularity, S=segmental sclerosis, T=tubular atrophy, UPCR, urinary protein creatinine ratio

The geographic and ethnic variation in the clinical presentation of IgAN is also very pronounced.[3,4,5] The frequency of hypertension at presentation varies widely between reported studies, ranging from 6% to 65%[23,26-28,39,47,48] [Table 5]. The prevalence of hypertension in the current study was high at 69.8%, consistent with a late presentation. Other Indian studies have similarly reported a high prevalence of hypertension, ranging from 35% to 84.1%.[49-52] In contrast to studies from India, which are predominated by patients who present late with advanced IgAN,[16,17] studies from East Asia[25,35,36,39] report a lower prevalence of hypertension, likely reflecting a patient population that presents earlier with greater access to screening programs and kidney biopsy [Table 6]. The geographic and genetic susceptibility differences is known in IgAN.[53]

In terms of risk factors for progression, our population was remarkable for the degree of proteinuria at presentation. The mean proteinuria of our cohort was 3.6 g/day, and 46.8% had nephrotic range proteinuria. Nephrotic syndrome is a rare presentation of IgAN, with previous studies reporting occurrence in 5%–10% of patient cohorts.[24,25,28] In this study, 15.2% of our patients presented with nephrotic syndrome. The higher incidence of nephrotic syndrome in our cohort may be due to inclusion of adolescent patients in the study. Prevalence of nephrotic range proteinuria at presentation has been reported in 23%–63% of previous Indian studies.[13-15,49-52] This is in sharp contrast to non-Indian studies [Table 5], where proteinuria at presentation is commonly much lower, ranging between 0.7 and 2 g/day and nephrotic range proteinuria is uncommon.[24,25,28,46,54,55] In Japan, a country known to have a high incidence of IgAN, nephrotic range proteinuria at presentation was seen in only 16% of patients.[19]

The reported prevalence of macroscopic hematuria also varies widely across studies, ranging from 11% in a study from South Korea[24] to 66% in a Japanese study.[29,32] Indian studies report a history of macroscopic hematuria in 5%–19% of cases.[14,15,40] In this study, macroscopic hematuria was seen in only 4.6% of cases, while microscopic hematuria occurred in 63.2% of cases. The higher prevalence of macroscopic hematuria found in the studies of Shima et al.[29] and Le et al.[25] may be due to the high number of children in their cohorts. Our cohort excluded pediatric cases less than 12 years of age; however, we included adolescent patients up to 18 years of age in our study cohort. Kidney failure at the time of presentation was also variably observed [22,24,38] [Table 5]. In the current study, the mean creatinine was 3 mg/dl, and 68% of cases had a raised serum creatinine at the time of presentation, with 54.8% of these patients having evidence of CKD at the time of presentation with eGFR less than 60 ml/min for more than 3 months. These findings again support a late presentation in our cohort.

Several clinical[40-42] and histological factors[43-45,56,57] affect the course and prognosis of IgAN patients. Studies from South Korea,[24] Japan,[19] and some studies from India[17,50,52] report mesangial hypercellularity as the most common histological lesion in IgAN. In parallel with the clinical findings in our cohort, advanced glomerulosclerosis was a common histological lesion, with 34.4% of cases showing DGGS at a mean age of 32 years. By contrast, in the study by Tsuboi et al.[56] from Japan, advanced glomerulosclerosis was seen in only 13.0% ± 14.8% of glomeruli in patients of similar age at presentation (mean age of 34 years). Consistent with our data, a high prevalence of advanced glomerulosclerosis has also been reported in another study from a tertiary care teaching institute in India.[15]

In the three most extensive validation studies of Oxford Classification from Japan,[19] China,[22] and Europe,[26] which included 702, 1026, and 1147 patients, respectively, there were distinct patterns of pathological features in each population. In the European cohort, endocapillary hypercellularity and crescents were reported in only 11% of cases.[26] The most common histopathologic lesion in this cohort was segmental sclerosis.[39] In the Chinese cohort, again, endocapillary proliferation was reported in 11%, but crescents were far more common and were seen in 48% of cases.[22] Again, the most common lesion in this cohort was segmental sclerosis. A study from Japan reported endocapillary proliferation in 42% of biopsies and crescents in 63% cases.[39] Table 5 summarizes the histopathologic features of published cohorts, demonstrating that these features vary both between countries and between regions in a country. The general trend appears to be that crescent and endocapillary proliferation are more common in the East Asian population compared to their western counterparts [Table 5]. In studies from India, mesangial hypercellularity and segmental sclerosis are the most commonly reported lesions.[15,17,50,52] The incidence of crescents varies from 10.7% to 56.6%.[15,50,52] In a recently published study from South India, there was a very low frequency of inflammatory glomerular lesions, but extensive glomerular segmental and global sclerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis at diagnosis, although this may reflect the inclusion criteria applied in this cohort.[42] The median global sclerosis was 32% only, though S and T scores were high. Crescents were low due to exclusion of eGFR <15 ml/min in the study by Alexander et al.[52] In our study, comparison of Oxford MEST-C scoring[20,57] showed mesangial hypercellularity (M1) in 67%, endocapillary hypercellularity in 23.9%, and crescents in 19.6% of cases. Consistent with the late presentation of our patients, moderate to severe tubular atrophy (>25% of cortex) was seen in 52.7% of our cohort. In line with the current literature, we identified a number of associations between clinical parameters and MEST-C score. Hematuria and proteinuria were significantly greater in patients with inflammatory glomerular lesions (E1 and C1/2). We also observed that increased mesangial C3 deposition, presumably reflecting glomerular complement activation through the lectin and alternative pathways (C1q was ubiquitously negative), was associated with a higher serum creatinine at presentation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study shows that patients are presenting late to our tertiary center in North India, resulting in a delayed diagnosis. This is reflected by a kidney biopsy demonstrating advanced glomerulosclerosis and significant interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Our IgAN population tends to have greater proteinuria, a higher incidence of kidney failure, and hypertension at the time of presentation than western and East Asian cohorts. There is, therefore, an urgent need for strategies to deliver an earlier diagnosis of IgAN, not only in North India but across the entire country.

Statement of ethics

The study was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. The study has been approved by the ethics committee of the institute (2020-301-DM-EXP-23).

Data availability statement

The research data are not publicly available on ethical grounds. The data are available with the corresponding authors and can be accessed after request from the corresponding author.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the histopathology technicians of the Department of Pathology for all help in carrying out the study.

References

- Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy and factors predictive of disease outcome. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24:179-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- The changing pattern of primary glomerulonephritis in Singapore and other countries over the past 3 decades. Clin Nephrol. 2010;74:372-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney disease screening program in Japan:History, outcome, and perspectives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:1360-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- A-nationwide study of mass urine screening tests on Korean school children and implications for chronic kidney disease management. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2013;17:205-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- The incidence of biopsy-proven IgA nephropathy is associated with multiple socioeconomic deprivation. Kidney Int. 2014;85:198-203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discovery of new risk loci for IgA nephropathy implicates genes involved in immunity against intestinal pathogens. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1187-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenesis of immunoglobulin a nephropathy:Recent insight from genetic studies. Annu Rev Med. 2013;64:339-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal disease in the elderly and the very elderly Japanese:Analysis of the Japan renal biopsy registry-(JRBR) Clin Exp Nephrol. 2012;16:903-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- A-retrospective analysis of the natural history of primary IgA nephropathy worldwide. Am J Med. 1990;89:209-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcomes and predictors of ESRD and mortality in primary GN. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1401-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Presentation, prognosis and outcome of IgA nephropathy in Indian adults. Nephrology-(Carlton). 2005;10:496-503.

- [Google Scholar]

- IgA nephropathy in Kerala, India:A-retrospective study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:14-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary IgA nephropathy in north India:Is it different? Postgrad Med J. 2012;88:15-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The spectrum of glomerular diseases in a single center:A-clinicopathological correlation. Indian J Nephrol. 2013;23:168-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlation of oxford MEST-C scores with clinical variables for IgA nephropathy in South India. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4:1485-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy:Pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. 2009;76:546-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation study of oxford classification of IgA nephropathy:The significance of extracapillary proliferation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2806-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy:A-systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62:891-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A-genome-wide association study in Han Chinese identifies multiple susceptibility loci for IgA nephropathy. Nat Genet. 2011;44:178-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- A-multicenter application and evaluation of the oxford classification of IgA nephropathy in adult Chinese patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:812-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The use of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy to predict renal survival. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2384-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy:A-single-center study in Korean adults. Korean J Intern Med. 2012;27:293-300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy for pediatric patients from China. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:158.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy in cohorts with different presentations and treatments. Kidney Int. 2014;86:828-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validation study of Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy:The significance of extracapillary hypercellularity and mesangial IgG immunostaining. Pathol Int. 2016;66:453-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A-validation study of crescents in predicting ESRD in patients with IgA nephropathy. J-Transl Med. 2018;16:115.

- [Google Scholar]

- Validity of the Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27:783-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the Schwartz and CKD-EPI equations for estimating glomerular filtration rate in children, adolescents, and adults:A-retrospective cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001979. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed. 1001979

- [Google Scholar]

- Glomerular disease frequencies by race, sex and region:Results from the International Kidney Biopsy Survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2018;33:661-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The clinicopathological characteristics of IgA nephropathy in Hong Kong. Pathology. 1988;20:15-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Natural history and risk factors for immunoglobulin A nephropathy in Japan. Research group on progressive renal diseases. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:526-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary glomerulonephritis in Singapore over four decades. Clin Nephrol. 2019;91:155-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global evolutionary trend of the prevalence of primary glomerulonephritis over the past three decades. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010;116:c337-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary IgA nephropathy:A-preliminary report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1995;38:233-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathologic predictors of renal outcome and therapeutic efficacy in IgA nephropathy:Validation of the Oxford classification. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:2175-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- An important role of glomerular segmental lesions on progression of IgA nephropathy:A-multivariate analysis. Clin Nephrol. 1994;41:191-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Oxford classification as a predictor of prognosis in patients with IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:252-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Overweight and obesity accelerate the progression of IgA nephropathy:Prognostic utility of a combination of BMI and histopathological parameters. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2012;16:706-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Severity of nephritic IgA nephropathy according to the Oxford classification. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44:1177-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical usefulness of the Oxford classification in determining immunosuppressive treatment in IgA nephropathy. Ann Med. 2017;49:217-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of outcome in paediatric IgA nephropathy with regard to clinical and histopathological variables-(Oxford classification) Nephrol DialTransplant. 2012;27:715-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis plays a major role in the progression of IgA nephropathy. II. Light microscopic and clinical studies. Kidney Int. 2011;79:643-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcomes of IgA nephropathy presenting with minimal or no proteinuria. J-Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1753-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy:A-retrospective analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2011;34:435-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- The MEST score provides earlier risk prediction in lgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2016;89:167-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prognostic factors in immunoglobulin-A nephropathy. J-Assoc Physicians India. 2002;50:1354-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and histopathologic profile of patients with primary IgA nephropathy in India. Renal Fail. 2016;38:431-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology, baseline characteristics and risk of progression in the first South-Asian prospective longitudinal observational IgA nephropathy cohort. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:414-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geographic differences in genetic susceptibility to IgA nephropathy:GWAS replication study and geospatial risk analysis. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002765.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features and outcomes of IgA nephropathy with nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:427-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glomerular density in renal biopsy specimens predicts the long-term prognosis of IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;5:39e44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy 2016:An update from the IgA nephropathy classification working group. Kidney Int. 2017;91:1014-21.

- [Google Scholar]