Translate this page into:

Fever of Unknown Origin in a Renal Transplant Recipient

Corresponding author: Subashri Mohanasundaram, Department of Nephrology, Government Stanley Medical College & Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: subashrimohan@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Mohanasundaram S, Srinivasaprasad ND, Fernando E, Thirumalvalavan K, Surendran S, Annadurai P. Fever of Unknown Origin in a Renal Transplant Recipient. Indian J Nephrol. doi: 10.25259/IJN_10_2024

Abstract

A syndrome of exaggerated lymphocytic proliferation and activation, called hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) can occur primarily due to genetic mutation, in children and secondary to infection, malignancy or autoimmunity in adults. It is characterized by a misdirected activation of immune system, which causes cytokine release from macrophages and cytotoxic cells, in an uncontrolled fashion. Most treatment protocols are formulated for primary hemophagocytic histiocytosis, which occurs in children, whereas awareness and therapeutic guidelines for the secondary form of the disease which affects predominantly the adults is limited. We present a 29 year old renal transplant recipient presenting with fever of unknown origin found to have HLH secondary to tuberculosis, who responded to anti-tuberculous treatment.

Keywords

Hemophagocytic lymphocytosis

Tuberculosis

Fever of unknown origin

Renal transplant

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), masquerading as sepsis, is a life-threatening syndrome that results from excessively activated immune system. It commonly presents as febrile illness that progresses to multi-organ dysfunction. It usually presents as a febrile disease progressing to multiple organ failure. Unless the treating physician has a high index of suspicion, the diagnosis of HLH may be missed leading to high mortality rate. While primary HLH results from genetic mutation, acquired (or secondary) HLH occurs mostly in the setting of infections, malignancies, or autoimmune disease. We describe a 29 year old renal transplant recipient who presented with fever of unknown origin.

Case Report

A 29-year-old man with native kidney disease focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) type underwent renal transplantation in 2018. His mother was the donor. In the first year posttransplantation, he had two episodes of acute cell-mediated rejection and posttransplant diabetes mellitus with baseline serum creatinine level of 1.8 mg/dL.

His admission in September 2019 was for fever and loose stools of six to seven episodes per day, for four days. He was on a daily dose of tacrolimus 7 mg, mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg, and prednisolone 5 mg. On examination, he was hypovolemic; his vitals were blood pressure of 100/70 mm Hg, pulse 120 bpm, temperature 102°F. System examination was otherwise normal. He was treated with intravenous fluids, empirical anthelmintics and antibiotics (nitazoxanide, ivermectin, piperacillin-tazobactam in renal adjusted dose) and stopped mycophenolate mofetil. Investigations revealed hemoglobin 8.4 gm percentage, total leucocyte count of 6600 cells/mm3, and platelet count of 109,000 cells/mm3. Urinalysis showed albuminuria (1+) and microscopic hematuria (+1). Blood urea was 94 mg/dL and serum creatinine was 4.4 mg/dL [Table 1]. On day six, since creatinine was 5.5 mg/dL, an allograft biopsy was done, revealing acute tubular injury, FSGS with moderate interstitial fibrosis, and tubular atrophy (40%–50%) without features of graft rejection or viral inclusion bodies.

| Laboratory investigations | Reference values | On admission | On day 6 | On day 15 | At discharge |

| Blood glucose (mg/dL) | 70-100 | 86 | 184 | 132 | 84 |

| Blood urea (mg/dL) | 8-21 | 94 | 129 | 89 | 111 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8-1.3 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| Serum electrolytes | |||||

| Sodium (mEq/dL) | 135-145 | 134 | 147 | 142 | 136 |

| Potassium (mEq/dL) | 3.5-5.0 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 3.6 |

| Chloride (mEq/dL) | 98-106 | 101 | 101 | 98 | 104 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/dL) | 23-28 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 24 |

| Complete blood count | |||||

| Hemoglobin (gm/dL) | 12.0-16.0 | 8.4 | 7.6 | 5.3 | 9.2 |

| Total leukocyte count (per µL) | 4500-11,000 | 6600 | 4000 | 1600 | 4200 |

| Differential leukocyte count (%) | |||||

| Neutrophils | 40-70 | 55 | 34 | 36 | 68 |

| Lymphocytes | 22-44 | 32 | 56 | 56 | 23 |

| Eosinophils | 4-11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| Monocytes | 0-8 | - | - | - | - |

| Basophils | 0-3 | - | - | - | - |

| Platelet count (per µL) | 150,000-400,000 | 109,000 | 98,000 | 64,000 | 113,000 |

| Serum Triglycerides (mg/dL) | <150 | - | - | 331 | - |

| Serum Ferritin (ng/mL) | 30-400 | - | - | 4544 | - |

| Serum Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 200-400 | - | - | 92 | - |

With persisting fever, he was empirically treated for invasive aspergillosis and cytomegalovirus infection.

By day 15, with persisting fever and nadir leukocyte count of 2200 cells per cu.mm, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were stopped. An extensive search for infection turned out inconclusive. He had developed moderate splenomegaly and progressive decline in blood cells of all three lineages. His serum triglycerides was 331 mg/dL, ferritin was 4544 ng/mL, and fibrinogen was 92mg/dL. The diagnosis of hemophagoytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) was made, according to the modified 2009 HLH criteria, due to the presence of five out of nine findings—which included fever, splenomegaly, peripheral blood cytopenia-hemoglobin <9g/dL, platelets <100,000/microL, hypertriglyceridemia, and serum ferritin >3000ng/mL.1

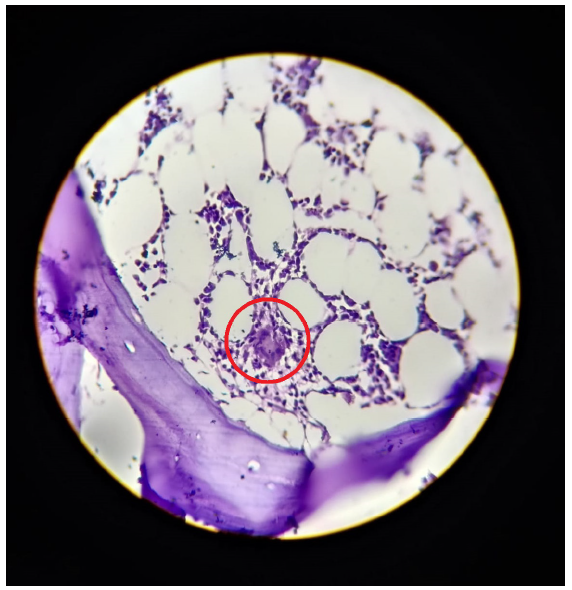

His bone marrow biopsy revealed hypocellular marrow with overall cellularity of about 15%–20% and small granulomas composed of epithelioid cells and langhan giant cells with spotty necrosis suggestive of tuberculosis [Figure 1]. On day 18, he developed minimal exudative pleural effusion with adenosine deaminase (ADA) of 74 U/L, which corroborated with the diagnosis of tuberculosis-associated HLH. He was treated with a short course of intravenous dexamethasone 4mg twice a day and was initiated on renal dose-adjusted antituberculous treatment (ATT) planned for 9 months.

- Bone marrow biopsy showing hypocellularity with small granuloma (within red circle) composed of epithelioid cells and Langhan giant cells with spotty necrosis.

After three weeks, his fever subsided, complete blood count improved, and serum creatinine settled down to 1.6 mg/dL. He was reinitiated on low-dose immunosuppressants and discharged in clinically stable condition.

Discussion

HLH remains an uncommon yet life-threatening condition that occurs as a result of aberrant immune activation and excessive cytokine production due to defective cytotoxic T-lymphocyte function.2 Secondary HLH can be triggered by malignancy, autoimmune disorders, immunodeficiency, and more. The most common precipitating event for secondary HLH in adults is infections due to Epstein-Barr Virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus.

The underlying mechanism of tuberculosis-HLH (TB-HLH) could possibly be due to the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis inside the phagocytes causing Th1-mediated cytotoxicity, thereby activating more macrophages and I confirm that the expansion is right, leading to cytokine storm (including IFN-γ, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), IL-1, IL-6, and IL-18) and the clinical symptoms.3,4

Renal allograft dysfunction secondary to TB-HLH can result commonly from acute kidney injury (due to increased capillary permeability and pre-renal ischemia), minimal change disease, collapsing glomerulopathy, acute tubular injury, and very rarely thrombotic microangiopathy. The pathogenesis behind the renal dysfunction is the surge of inflammatory cytokines, especially TNFα, and cytokine-mediated endothelial injury.5

In our patient, we had withheld all immunosuppressants except steroids and treated with an appropriate dose of ATT. Since the patient started responding to ATT, intravenous immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis was not administered.6 After an adequate improvement in allograft function, the patient was slowly reinitiated on immunosuppressants except mycophenolate mofetil, as the drug may precipitate HLH.7 During the subsequent year, the patient had developed recurrence of FSGS and was initiated on maintenance hemodialysis.

Conclusion

HLH is an uncommon condition resulting from heightened yet defective immune activation. Our patient emphasizes the importance of HLH as an important differential diagnosis among transplant recipients, who present with fever of unknown origin. To our knowledge, our patient is the first renal transplant recipient who has had HLH secondary to tuberculosis.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Dr. A. Viknesh Prabu, Consultant Physician, for his help in editing this manuscript.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;2009:127-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Similar but not the same: Differential diagnosis of HLH and sepsis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;114:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predictive value of interferon-γ release assays for incident active tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:45-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- An update on renal involvement in hemophagocytic syndrome (macrophage activation syndrome) J Nephropathol. 2016;5:8-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Haemophagocytic syndrome – A life-threatening complication of renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2623-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mycophenolate mofetil: A possible cause of hemophagocytic syndrome following renal transplantation? Am J Transplant. 2010;10:2378-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]