Translate this page into:

Histological Spectrum of Hepatitis-Virus Associated Glomerulonephritis

Corresponding author: Vinita Agrawal, Department of Pathology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, India. E-mail: vinita@sgpgi.ac.in; vinita.agrawal15@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Yadav R, Sengar P, Prasad N, Jain M, Prasad P, Agrawal V. Histological Spectrum of Hepatitis-Virus Associated Glomerulonephritis. Indian J Nephrol. doi: 10.25259/IJN_247_2024

Abstract

Background

Hepatitis virus-associated glomerulonephritis (HVGN) is a recognized extrahepatic manifestation of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. We report the prevalence and histological spectrum of HVGN in a tertiary care center in North India.

Materials and Methods

The study was done on renal biopsies of patients showing serological evidence of HBV and/or HCV infection (2014-2022). Clinical data and viral serological markers were recorded. Renal biopsies were evaluated by light microscopy, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. Surface antigens in HBV-positive patients were detected using immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Results

A total of 5179 native kidney biopsies were collected, of which 49 and 10 tested positive for HBV and HCV infection, respectively. IgA nephropathy (IgAN) (26.5%), followed by membranous nephropathy (16.3%), were the most common histological patterns in HBV-associated renal disease. The most common histologies were membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) pattern of injury (20%) and IgAN (20%). At the time of renal biopsy, liver function tests were deranged in 37% (n=18) and 40% of (n=4) HBV and HCV patients, respectively. IHC of no renal biopsies of patients with HBV infection were positive for HbsAg.

Conclusion

IgAN is the most common glomerulonephritis (GN) associated with HBV infection and MPGN and IgAN were most commonly HCV-related GN.

Keywords

HBV

HCV

Hepatitis virus-associated glomerulonephritis

IgAN

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

Renal biopsy

Introduction

Hepatitis virus-associated glomerulonephritis (HVGN) is a recognized extrahepatic manifestation of Hepatitis B (HBV) and C viral (HCV) infections.1-3 Pathogenesis of HVGN includes immune complex-mediated injury, direct cytotoxic viral effects, and/or due to cryoglobulins.4 Glomerular disease can occur in 2.6–4.3% of patients with chronic HBV infection.5-8 The histological spectrum of HBV-associated GN commonly includes membranous nephropathy (MN), membranoproliferative glomerulonephriti (MPGN), IgA nephropathy (IgAN), and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).9 In HCV-associated GN, the glomerular pathology is commonly MPGN with or without Type 2 cryoglobulinemia, followed by MN, FSGS, and mesangioproliferative GN.3 Studies on hepatitis virus-associated renal disease are limited. The time between the detection of hepatitis via serology and the development of HVGN needs to be documented.

The factors for the renal prognosis of HVGN are not well-documented. There are no reports on HVGN from Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. We report the prevalence and histological spectrum of HVGN in a tertiary care center in North India.

Materials and Methods

The study included renal biopsies of patients with serological evidence of HBV and/or HCV infection over nine years (2014 to 2022) received in the Department of Pathology, SGPGIMS. Patients with HBsAg, HBV DNA, HCV antibody, and HCV RNA positive serology were included.

Clinical data and viral serology, namely HBsAg, HBeAg, HBe-Ab, HBV DNA, and HCV RNA levels were retrieved. Laboratory parameters, including autoimmune workup, urinalysis, seruigm biochemistry, and serum complement levels were noted from the records. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation. Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy criteria of tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis was used to assess the degree of tubulointerstitial injury.

All the biopsies were processed for light microscopy, immunofluorescence (IF), and electron microscopy using the standard protocol and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E).

Sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) renal tissue were analyzed by IHC using prediluted HbsAg (A10F1, Master Diagnostica, Spain). The staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions on a BenchMark-XT slide stainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.). Liver biopsy tissue from an HBsAg-positive patient was used as a positive control. The Institute Ethics Committee approved the study (2024-151-IP-EXP-59) and patient consent was obtained.

Results

A total of 5179 native kidney biopsies were received between January 2014 and December 2022 in the department of pathology, SGPGIMS, Lucknow. HbsAg was positive in 49 patients; HBV DNA levels ranged from 20 to 406 million/IU. HCV antibody was positive in 10 patients, HCV RNA levels ranged from 1.64 to 3319 million/IU. The prevalence of HVGN was 1.1%, mostly due to HBV-related GN (0.95%), which constituted 83% of all HVGN.

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical features of HBV- and HCV-related GN. Transmission electron microscopy and evaluation were available for 21 biopsies. The findings were incorporated while analyzing the biopsies.

| Parameters | HBV-related GN (n=49) | HCV-related GN (n=10) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||

| Age, years | 35.7 ± 15.7 | 38.2 ± 12 | 0.637 |

| Gender (M/F) | 36/13 (73.5% vs 26.5%) | 7/3 (70% vs 30 %) | 0.822 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 24 (49%) | 4 (40%) | 0.604 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (6%) | 2 (20 %) | 0.151 |

| Chronic liver disease, n (%) | 5 (10%) | 3 (30%) | 0.217 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 3.06 ± 2.7 | 1.9 ± 1.7 | 0.231 |

| Proteinuria (g/day) | 3.8 ± 2.6 | 4.3 ± 5 | 0.359 |

| Serum protein (g/dL) | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 0.108 |

| Serum albumin (g/dL) | 3 ± 0.9 | 3.3 ± 0.67 | 0.370 |

| Proteinuria, n (%) | 43 (87.8 %) | 9 (90 %) | 0.841 |

| Hematuria, n (%) | 28 (57%) | 8 (80%) | 0.176 |

| Serum C3, mg/dL | 100.9 ± 33.2 | 119.5 ± 59.5 | 0.191 |

| Serum C4, mg/dL | 37.4 ± 17.2 | 31.3 ± 14.7 | 0.501 |

| SGOT, IU/L | 47.8 ± 10 | 75.9 ± 7.9 | 0.165 |

| SGPT, IU/L | 40.2 ± 7.2 | 97.9 ± 64.9 | 0.030* |

| ALP, IU/L | 154.7 ± 10.3 | 137.9 ± 24.6 | 0.669 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 53 ± 45.7 | 67.9 ± 43.2 | 0.348 |

| CKD I/II, n (%) | 15 (30.6 %) | 6 (60%) | 0.076 |

| CKD III-V, n (%) | 34 (69.4 %) | 4 (40%) | |

| Histological features | |||

| IgA Nephropathy, n (%) | 13 (26.5%) | 2 (20 %) | 0.665 |

| MN, n (%) | 8 (16.3%) | 0 | 0.169 |

| DGGS, n (%) | 8 (16.3 %) | 1 (10 %) | 0.612 |

| MCD, n (%) | 3 (6.1 %) | 1 (10 %) | 0.656 |

| FSGS, n (%) | 3 (6.1 %) | 1 (10 %) | 0.656 |

| MPGN, n (%) | 2(4 %) | 2 (20 %) | 0.068 |

| Amyloidosis, n (%) | 3 (6.1 %) | 0 | 0.421 |

| Pauci-immune crescentic GN, n (%) | 3 (6.1 %) | 0 | 0.421 |

| Mesangioproliferative GN, n (%) | 0 | 2 (20 %) | 0.002* |

| Cryoglobulinemic GN, n (%) | 0 | 1 (10%) | 0.395 |

| ATN, CTIN, or TIN, n (%) | 6 (12 %) | 0 | 0.243 |

| Overall | 0.361 | ||

| Tubular and interstitial injury scores (as per MEST classification) | |||

| 0, n (%) | 30 (61 %) | 7 (70 %) | 0.319 |

| 1, n (%) | 10 (21 %) | 3 (30 %) | |

| 2, n (%) | 9 (18 %) | 0 | |

ALP: Alkaline phosphatase, ATN: Acute tubular necrosis, CKD: Chronic kidney disease, CTIN: Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis, DGGS: Diffuse global glomerulosclerosis, eGFR: Estimated glomerular filtration rate, FSGS: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, GN: Glomerulonephritis, MN: Membranous nephropathy, MPGN: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, MCD: Minimal change disease, TIN: Tubulointerstitial nephritis, SGOT: Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase, SGPT: Serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase, HBV: Hepatitis B virus, HCV: Hepatitis C virus, MEST: Oxford classification for IgAN-Mesangial proliferation, Endocapillary proliferation, Segmental sclerosis, Tubular atrophy. *significant P value.

HBV-related renal disease

Of 49 patients, 12 were known to be HBsAg positive, and 37 were detected during workup for renal disease. In the former group, the duration from HBV infection to onset of renal disease was 8-168 (median-24) months [Table 1]; five patients (41%) were on antiviral therapy, and three were on remission. They also had a significantly (p=0.028) higher (33%) incidence of chronic liver disease (CLD) as compared to the newly diagnosed (6.8%).

Nephrotic-range proteinuria was observed in 27 patients (55%). Liver function tests were deranged in 18 (37%), of which 4 (8%) previously had HBV infection. One patient, positive for HBsAg, was co-infected with HIV. No significant clinical and histological features were associated with the presence of HBeAg.

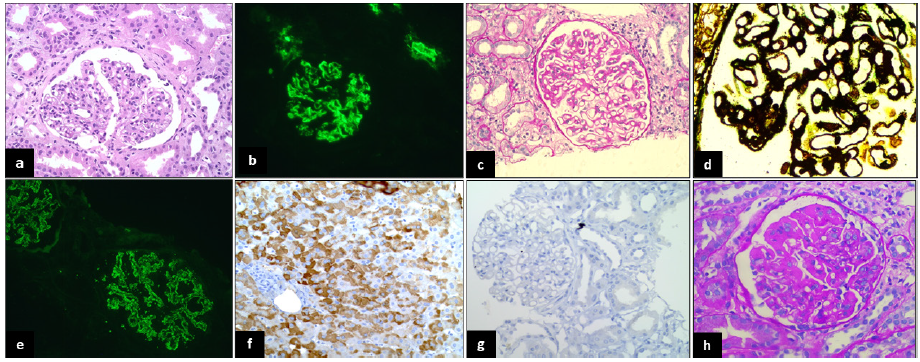

IgAN (n=13; 26.5%) was the most common histological diagnosis [Figure 1a-b], followed by membranous nephropathy (n=8; 16.3%) [Figure 1c-e]. The other histological patterns included diffuse global glomerulosclerosis (DGGS) (n=8; 16.3%), minimal change disease (n=3; 6.1%), FSGS (n=3, 6.1%), amyloidosis (n=3; 6.1%), pauci-immune crescentic GN (n=3; 6.1%), and immune-complex mediated MPGN (n=2; 4%,). Tubulointerstitial pathology (acute tubular injury and tubulointerstitial nephritis) was noted in six (12%) biopsies. Histology for patients co-infected with HIV showed IgAN. Histology of five patients with CLD showed DGGS (n=2), MN (n=1), IgAN (n=1), and MPGN (n=1).

- IgA nephropathy: (a) Glomerulus shows diffuse mesangial hypercellularity (H&E,400x); (b) 3+ glomerular mesangial immune deposit (IF,400x). Membranous nephropathy (MN): (c) Glomerulus is enlarged with thickened and stiff capillary loops (PAS,400x); (d) Glomerulus showing subepithelial argyrophilic spikes (PASM, 400x); (e) 3+ fine granular subepithelial immune deposits (IF, 400x). (f) Positive control of Hepatitis B-virus (HBV) surface antigen IHC in a case of HBV positive liver biopsy (IHC,400x); (g) A case of MN negative for immunohistochemistry (IHC,400x). Cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis: (h) Glomerulus shows fuchsinophilic subendothelial deposits and intra-capillary hyaline thrombi (MT,400X).

Most biopsies of IgAN showed segmental sclerosis (S1) (9/13) and mesangial hypercellularity (M1) (7/13). Only two biopsies showed endocapillary hypercellularity (E1), and one showed crescents (C1); significant tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (T1-2 lesions) were present in six. In MN, one biopsy was PLA2R IHC positive, and three had raised serum anti-PLA2R levels. Two patients were not tested for serum PLA2R. IF did not show light chain restriction in all three amyloids and serum electrophoresis was negative for monoclonal proteins. Two patients had a history of long-standing tuberculosis, suggesting associated Serum Amyloid A (SAA).

IHC was performed in 40/49 biopsies, and none were positive for HBsAg expression [Figure 1f-g].

HCV-related renal disease

Workup for renal biopsy showed HCV infection in 7/10 patients. In already known HCV-positive patients (n=3), the onset of renal disease was after 18-84 months (median-36 months). Treatment with direct-acting antivirals sustained virologic response in all.

Half (50%) of patients had nephrotic-range proteinuria. Liver function test was deranged in 40% (n=4), of whom only one was previously known to be HCV-positive.

The most common histological patterns were MPGN [n=2; 20% (one immune-complex mediated and other C3GN with DN)] and IgA nephropathy (n=2; 20%). Other patterns were mesangioproliferative GN without IgA deposits (n=2; 20%; both had no immune deposits), DGGS (n=1; 10%), MCD (n=1; 10%), FSGS (n=1; 10%), and cryoglobulinemic GN (n=1; 10%) [Figure 1h].

Between patients with HCV- and HBV- associated renal disease, the former had significantly (p=0.030) higher liver enzymes. Patient demographics and laboratory parameters showed no significant difference between HBV- and HCV-associated GN [Table 1].

All patients received appropriate treatment including antiviral therapy. Steroids were deferred in all newly diagnosed patients with HBV or HCV infection to avoid a viral infection flare-up. Patients with FSGS and minimal change disease were given antiviral therapy to which steroids were eventually added.

For 27 patients with HVGN, the follow up duration was 6 -36 months (median- 20 months). Follow-up was available in 22/49 patients with HBV-associated renal disease. Of the six IgAN patients, half and half showed complete and partial remission, one of which was also HIV positive. All three patients with FSGS had a partial response. The two patients with membranous nephropathy showed partial to complete response. All patients with pauci-immune crescentic GN (n=3), DGGS (n=5), amyloidosis, MPGN, and tubulointerstitial nephritis remained dialysis-dependent.

Follow-up was available in 5/10 patients with HCV-associated renal disease. Both patients with IgAN showed remission. However, one patient, each of FSGS and MCD, showed no response to therapy. The patient with DGGS remained dialysis dependent. The latter was recently detected with multiple myeloma and was on a bortezomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (VCD) regimen (with a difference of 7 years from diagnosis to need of renal biopsy).

Discussion

The prevalences of HBV and HCV infection in India are 0.87-21.4% and 0.19- 53.7%, respectively.10 The data on hepatitis virus-associated renal disease from India and Southeast Asia are limited. We studied the prevalence and clinicopathological characteristics of HBV and HCV-associated renal disease over nine years in a tertiary care Institute in North India.

We observed a 1.1% prevalance of HVGN, primarily due to HBV-related GN (0.95%), which is much lower than other Asian countries, like China, where it has been reported as 2.6-4.3%.5-8

The pathogenesis of hepatitis-associated GN involves the deposition of in-situ or circulating immune complexes, virus-induced immunological effector mechanisms, or direct cytotoxic glomerular or tubular injury.11 The size, charge, and molecular weights of hepatitis antigens determine their pathogenicity and location of immune deposits.12 Formed HBeAg antigen-antibody immune complexes are cationic and small and tend to deposit in the subepithelial region. In contrast, HBsAg or HBcAg-antibody complexes are anionic and large and restricted to the mesangial and subendothelial regions.2 Renal tubular epithelial cells have been known to express HBsAg and HBcAg.13 Studies show that serum from patients of chronic hepatitis B promotes apoptosis of renal tubular cells by upregulating the Fas-signaling pathway.14

In our study, IgAN and concomitant MPGN and IgAN were the most common renal manifestations of HBV and HCV-associated renal diseases, respectively. The higher prevalence of IgAN could be related to liver dysfunction in these patients. In contrast, Kong et al.15 and Chen et al.16 reported MN as the most common GN. However, Zhang et al.17 reported mesangioproliferative GN as the most common type. HBV infection was identified as an independent risk factor for CKD in rural China.18

Kong et al., studied 500 renal biopsies and detected HBsAg and HbcAg by IHC in only three (0.6%) and six (1.2%) of them, respectively.15 IHC of all biopsies in our study were negative for HBsAg, despite a positive control in each staining batch. This may be because we performed IHC on FFPE tissue, while many of the previous studies demonstrated immune staining on frozen tissue.15,17 Similar results were observed by Nikolopoulou A et al. when they evaluated the staining in six renal biopsies.19 Zhang Y et al. detected HBsAg in all ten biopsies with acute post-infectious HBV GN.20 Chen et al. and Zhang et al. demonstrated HBsAg in 76.2% and 41.3% of renal biopsies, respectively.16,17 Table 2 shows the summary of various studies evaluating IHC for HBsAg in renal biopsies of positive patients. Prospective studies utilizing more sensitive methods on fresh renal tissue in known HBV/HCV patients are required to understand the pathogenesis of HV-associated renal disease.

| Study | Detection Method (IHC, paraffin/frozen) | HBsAg | HBcAg |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chen L et al.16 | IHC (paraffin section) | 76.2% (48/63) | 42.9% (27/63) |

| Zhang L et al.17 | IHC (frozen section) | 41.3% (136/329) | 43.5 % (143/329) |

| Kong D et al.15 | IHC (frozen section) | 0.6% (3/500) | 1.2% (6/500) |

| Zhang Y et al.20 |

Immunoperoxidase (paraffin section) Only in HBV-PIGN |

100% (10/10) | Not done |

| Nikolopoulou A et al.19 | IHC (paraffin) only in HBV MN | Not detected (0/6) | Not done |

| Present study | IHC (paraffin section) | Not detected (0/40) | Not done |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus, IHC: Immunohistochemistry, HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen, HBcAg: Hepatitis B core-antigen, PIGN: Postinfectious glomerulonephritis, MN: Membranous nephropathy, GN: Glomerulonephritis.

On follow-up, 15% of our patients developed end-stage renal disease, requiring renal transplant. There are studies on the effect of HBV infection in renal transplant recipients. HBsAg-positive kidney transplant recipients face a 2.5- and 1.5-fold higher mortality risk and risk of allograft loss, respectively.21 There was 80% graft survival after 6 months of transplantation in HCV-positive renal transplant recipients compared to 91% in HCV-negative patients (p < 0.001).22 Mo et al. found significant differences in survival between positive and negative HBsAg patients and those receiving antiviral therapy (p = 0.020). The study concluded that lifelong antiviral therapy is essential, and patients with high preoperative HBV titers should be closely monitored for reactivation.23

The European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines suggest that combined liver and kidney transplantation should be considered in cirrhotic patients with renal disease.24 Direct-acting antiviral therapy has significantly improved outcomes in HCV-positive renal transplant recipients.25 Therefore, studies are needed to determine if patients with hepatitis C can undergo kidney transplants with acceptable long-term outcomes.

In conclusion, we present our study of HBV and HCV-related renal disease, with a focus on HBV. IgAN was the most common GN associated with HBV infection, while MPGN, both immune-complex mediated and C3GN, and IgAN were most common in HCV-related GN. We suggest routine screening of all patients with renal disease for hepatitis infection.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hepatitis B virus infection: Implications in chronic kidney disease, dialysis and transplantation. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2006;35:111-9.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis B virus-associated nephropathy in black South African children. Pediatr Nephrol. 1998;12:479-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renal involvement in hepatitis C infection: Cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1998;54:650-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glomerular diseases Associated with hepatitis B and C. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22:343-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of biopsy proven renal diseases in Central China: A 10-year retrospective study based on 34,630 cases. Sci Rep. 2020;10:10994.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of pathological data of renal biopsy at one single center in China from 1987 to 2012. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:1715-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The spectrum of biopsy-proven glomerular disease in China: A systematic review. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018;131:731-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and pathological analysis of 4910 patients who received renal biopsies at a single center in Northeast China. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:6869179.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Viral-associated GN: Hepatitis B and other viral infections. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:1529-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of viral hepatitis infection in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Educ Health Promot. 2023;12:103.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Purified hepatitis B virus induces human mesangial cell proliferation and extracellular matrix expression in vitro. Virol J. 2013;10:300.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Primary glomerulonephritis in China. Analysis of 1001 cases. Chin Med J (Engl). 1989;102:159-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gene expression profile of transgenic mouse kidney reveals pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus associated nephropathy. J Med Virol. 2006;78:551-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic hepatitis B serum promotes apoptotic damage in human renal tubular cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1752-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Detection of viral antigens in renal tissue of glomerulonephritis patients without serological evidence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e535-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Replication and infectivity of hepatitis B virus in HBV-related glomerulonephritis. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:394-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The relationship between HBV serum markers and the clinicopathological characteristics of hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis (HBV-GN) in the northeastern Chinese population. Virol J. 2012;9:200.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Association between hepatitis B virus infection and chronic kidney disease: A cross-sectional study from 3 million population aged 20 to 49 years in rural China. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e14262.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Membranous nephropathy associated with viral infection. Clin Kidney J. 2020;14:876-83.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- HBV-Associated postinfectious acute glomerulonephritis: A report of 10 cases. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0160626.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of kidney transplantation in patients with hepatitis B virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Hepatol. 2018;10:337-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Short and long term outcome of kidney transplanted patients with chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Ann Hepatol. 2010;9:271-7.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcome after kidney transplantation in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11:11744.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of patients with hepatitis C undergoing simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation. J Hepatol. 2009;51:874-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Is it time to rethink combined liver-kidney transplant in hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis? World J Hepatol. 2017;9:288-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]