Translate this page into:

Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Nephrology Training in an Academic Center in India: Looking Forward Through Online Teaching

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

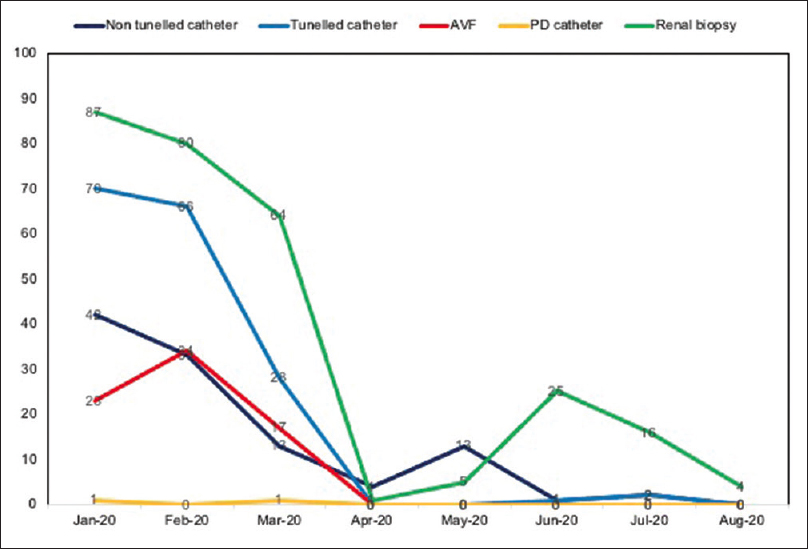

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has greatly impacted medical education. While there is a lot of talk on reforms in undergraduate medical education in India[1] and worldwide,[2] traditional face-to-face didactic teaching is still the standard method of post-graduate teaching in India. Newer solutions must be adopted to continue medical training during COVID-19 pandemic.[3] The usual structure of nephrology training at our center comprises of academics, procedural training, in-patient management skills and research. Nephrology fellows attend both inter- and intra-departmental classes. On an average, each fellow does ~200-250 procedures, including kidney biopsy, tunneled hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis catheter insertion, creation and cannulation of arteriovenous fistula, in their 3-year training period. Typically, admitted patients are analyzed by the fellows and residents with critical thinking and problem-solving approach. Bedside ward rounds with faculty then focuses on decision-making. This also allows soft skill development by simply observing senior faculty interact with patients. Increase in COVID-19 care led to drop in admission facilities for non-COVID patients, cut-down in elective procedures [Figure 1], posting of nephrology fellows in COVID-care areas and quarantine policies restricting fellows and faculties in non-COVID areas. Ward rounds were cut down in terms of number and attendees with resultant cracking down of bedside teaching. Physical face-to-face classes were instantly discontinued in the beginning of the pandemic (April 2020) and replaced by online classes which are held more systematically for the last 3 months. Efforts were made to continue the training program, however, there are obvious and hidden lacunae.

- Trend of elective procedures during COVID-19 pandemic

We undertook a survey among the 14 nephrology fellows in our center in the form of a self-administered checkbox questionnaire [Table 1]. The survey was done on a pilot basis to assess the utility of online learning and identify potential areas for improvisation. All the fellows attended all the online classes conducted in the department for the past 3 months and all of them responded to the questionnaire within 24 hours. The questionnaire (10 questions) response was collected maintaining anonymity. These questions covered 2 domains. There were 6 questions in domain 1; among 5 Likert-scale based questions (questions #2-6), response <3 favored online classes and response >3 favored physical classes. Most (78.6%) fellows found physical classes to be better than online classes (question #1) and common reasons were: “face-to-face classes provide platform for better interaction between fellows and faculty” and “physical presence ensures better attentiveness of all the attendees”. Median scores for all questions in domain 1 (except question no. 2) was >3, suggesting quality of physical classes to be better than online classes. In domain 2, question #8 revealed that 71.4% were interested in having polls or questions during online classes. Among the 4 best ways to continue teaching during pandemic (question #9), 43% opted for online discussion with one-to-one interaction, and 36% opted for small-group didactics with adequate social distancing. Regular virtual rounds (online) with residents and faculty-in-charge were felt to be best substitute of bedside teaching during the pandemic by 85.7% fellows.

| Domain 1: Quality of online classes compared to physical classes | Responses (%; median (IQR) scores) |

|---|---|

| In your last 8 months of experiencing both physical face-to-face classes (in the early part of this year) and online classes (in the last 3 months), what do you think holds true? Physical classes are better than online classes, B. Physical classes are similar to online classes, C. Physical classes are worse than online classes |

A.78.6%, B. 14.3%, C. 7.1% |

| How much effort did you put into adapting to online classes? Almost no effort, B. A little bit effort; C. Some effort, D. Quite a bit effort, E. A great deal of effort |

2 (2-3) |

| How often has the fear of missing out on “usual learning” crossed your mind during the last month? Almost never, B. Once in a while, C. Sometimes, D. Often, E. Almost always |

4 (2.75-4.25) |

| How much are you interested in continuing to have online classes even after the pandemic ends? Extremely interested, B. Quite interested, C. Moderately interested, D. Slightly interested, E. Not at all interested |

4 (2.75-5.0) |

| How important is learning through physical interaction in one-to-one and/or small groups with your fellow trainees while working? Not important, B. Slightly important, C. Moderately important, D. Quite important, E. Essential |

5 (4-5) |

| How important is the informal discussion (reinforcing or defying the content discussed) immediately after the physical classes with your fellow trainees for you? Not important, B. Slightly important, C. Moderately important, D. Quite important, E. Essential |

5 (4-5) |

| Domain 2: Ways to increase utilization of online teaching | |

| How confident are you that simulation-based learning will make you ready for procedures? Not at all confident, B. Slightly confident, C. Moderately confident, D. Quite confident, E. Extremely confident |

2 (1-3) |

| How much are you interested in having polls or questions intermittently during the online classes? Not at all interested, B. Slightly interested, C. Moderately interested, D. Quite interested, E. Extremely interested |

3 (2-4) |

| What, in your view, is the best way to continue teaching during the pandemic? Online discussion with one-to-one interaction, B. Webinars, C. WhatsApp group for discussing important topics, D. Small-group didactics |

A.42.9%, B. 21.4%, C. 0, D. 35.7% |

| How do you think ward rounds and bedside teaching be substituted in this pandemic? Have virtual rounds (online) with residents and faculty-in-charge, B. Have WhatsApp group discuss the important issues, C. Some other way |

A.85.7%, B. 0, C. 14.3% |

While we did not validate the questionnaire, the survey findings provided a quick feedback. It revealed that despite having to put in minimal to no effort into adapting to online classes, most of the fellows were not satisfied with the quality of online classes. This finding is similar to another study among medical graduates attending online classes which found 50% of students to prefer physical classes over online classes despite easy practicability of online learning.[4] With the feedback from the survey, we have planned following improvisations: 1). Online sessions to be better utilized by having chat-box questions, polls, individual-directed questioning, 2). Virtual ward rounds using power point presentation between faculty and fellows for day-to-day patient management, 3). Small-group didactics with adequate distancing on interesting cases and topics. To conclude, online teaching can partly compensate for the academic loss during this pandemic. We believe finding new strategies to increase utility of online classes would not only serve the purpose during this pandemic but also make e-learning a crucial component of training post-graduates in the future.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Medical education in India: Past, present, and future. APIK J Int Med. 2019;7:69-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A single institution experience. Indian Pediatr. 2020;57:678-9.

- [Google Scholar]