Translate this page into:

Long-term prognosis of IgA nephropathy presenting with minimal or no proteinuria: A single center experience

Address for correspondence: Dr. N. Imai, Division of Nephrology and Hypertension, St. Marianna University School of Medicine, 2-16-1 Sugao, Miyamae-ku, Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Japan. E-mail: imaix006@umn.edu

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The long-term prognosis of patients with IgA nephropathy (IgAN) who present with preserved renal function and minimal proteinuria is not well described. We investigated the long-term outcomes of IgAN patients with an apparently benign presentation and evaluated prognostic factors for renal survival and clinical remission. We studied Japanese patients with biopsy-proven IgAN who had an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and proteinuria <0.5 g/day at the time of renal biopsy. The renal biopsies were reviewed using the Oxford classification. Twenty patients met the inclusion criteria. At diagnosis, the median eGFR (interquartile range) was 76.8 (65.2–91.1) mL/min/1.73 m2, and the median proteinuria level was 0.31 (0.16–0.39) g/day. Only one patient had an increase in serum creatinine of over 50% and no patient progressed to end-stage renal disease. The 15-year renal survival rate was 93.8%. Clinical remission was observed in 9 (45%) patients. Baseline proteinuria was the only factor significantly associated with the absence of clinical remission. The long-term prognosis of Japanese patients with IgAN who presents with minor urinary abnormalities and preserved renal function is excellent.

Keywords

Glomerulonephritis

IgA nephropathy

Japan

Introduction

IgA nephropathy (IgAN) is the most common primary glomerulonephritis worldwide.[1] It is also the most common primary glomerulonephritis in Japan.[2] The dominant mesangial IgA deposits represent the diagnostic hallmark of IgAN. Its clinical features are highly variable, ranging from simple hematuria with or without proteinuria to a rapidly progressive loss of renal function.[3] Progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) occurs in 10–50% of patients, usually developing slowly over 20 years.[45]

Few studies have focused on patient and renal outcomes in biopsy-proven IgAN patients with minimal proteinuria and normal renal function, and the results of previous studies are controversial.[678910] Research performed in Korea found that 4% of patients progressed to ESRD, and 25% of patients achieved clinical remission.[6] On the other hand, a study from Europe found that no patients progressed to ESRD and 38% of patients achieved clinical remission.[9] The Oxford classification system has not previously been applied to IgAN patients with minimal abnormalities at presentation in an Asian population. Our study focused on long-term outcomes and prognostic factors for renal survival and clinical remission in clinically benign IgAN patients using the Oxford classification system.

Subjects and Methods

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of St. Marianna University Hospital, Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Japan. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. As the study was retrospective in design and did not involve any interventions, the Institutional Review Board waived informed consent for this study.

Patients

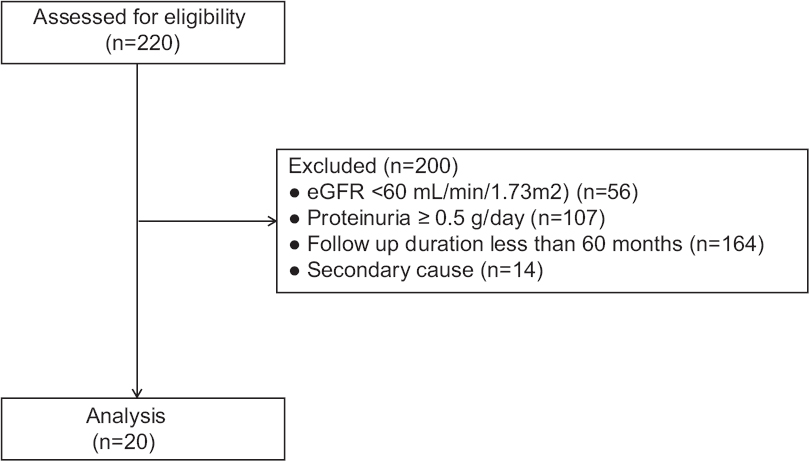

Inclusion criteria were renal biopsy-proven IgAN, preserved renal function (defined by estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2), and minimal proteinuria (defined by urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio <0.5 g/g or 24 h urinary protein <0.5 g/day). All the patients were biopsied for microscopic hematuria or an episode of microscopic hematuria with dysmorphic red blood cells. Patients with Henoch–Schönlein nephritis, liver cirrhosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or any type of secondary IgAN were excluded. Patients who were followed for <5 years were also excluded. Twenty patients met these criteria from 1991 to 2000, and they were included in the study [Figure 1].

- Participation flow diagram

Data collection

Patients underwent regular assessments at intervals of 3–6 months. Clinical information was collected from a review of computerized medical records. The following data were systematically recorded: sex, age at kidney biopsy, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure at kidney biopsy, serum total protein, serum albumin, serum total cholesterol, proteinuria and urine sediment. Proteinuria and urine sediment were tested at every visit throughout follow-up, even in patients in whom hematuria and proteinuria had disappeared. Urine sediment was examined in a centrifuged and concentrated sample of the urine using standardized methodology. Proteinuria was assessed using either a random urine protein-to-creatinine ratio or 24 h urinary protein measurement (lower limit of detection 0.02 g/day). Absence of proteinuria at baseline was defined by proteinuria lower than 0.2 g/day. Proteinuria was measured using the sulfosalicylic acid method. The new equation proposed by the Japanese Society of Nephrology was used to calculate the eGFRs, as follows: eGFR = 194 × (creatinine)−1.094 × age−0.287 (or × 0.739 if female).[11] Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure >140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg. All treatments were recorded during the follow-up period, including exposure to steroids, tonsillectomy, and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers.

Renal biopsy

Diagnosis of IgAN was established when there was predominant IgA staining using immunofluorescence, and the intensity of IgA staining was more than trace. The distribution of IgA staining included staining in the mesangium, with or without capillary loop staining. IgG, IgM, and C3 could be present, but only if they exhibited a lower staining intensity than IgA. The histologic findings were graded according to the Oxford classification, which scored four key pathologic features in each specimen.[1213] Mesangial hypercellularity was scored as M0 if >50% of glomeruli had fewer than three cells per mesangial area or M1 if >50% of glomeruli had more than three cells per mesangial area. Segmental glomerulosclerosis was scored as absent (S0) or present (S1). Endocapillary hypercellularity was scored as absent (E0) or present (E1). The tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis score was based on the ratio of tubular atrophy to interstitial fibrosis in the total interstitium and scored as T0 (0–25%), T1 (26–50%), or T2 (>51%).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were renal survival (defined by a status free of persistent serum creatinine (SCr) increase >50% from baseline throughout the follow-up and no ESRD) and clinical remission (defined by preserved renal function, proteinuria persistently <0.2 g/day, and the persistent disappearance of microscopic hematuria throughout the follow-up). ESRD was defined as progression to an eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2, initiation of permanent dialysis or kidney transplantation. The date of renal biopsy was defined as the start of the follow-up period. The secondary outcome was the presence of a final proteinuria >0.5 g/day.

Statistical analyses

Quantitative variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). When comparing parameters between two groups, parametric data were compared using unpaired t-tests, and nonparametric data were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Qualitative variables were described using frequency and percentages and were analyzed using Fisher and Chi-squared tests. Cumulative renal survival and clinical remission were determined using the Kaplan–Meier method. Univariate analysis of clinical events was determined by Cox model when applicable. Multivariate analysis was not performed because of the relatively small number of patients selected. A P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software (version 21.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics and histologic findings

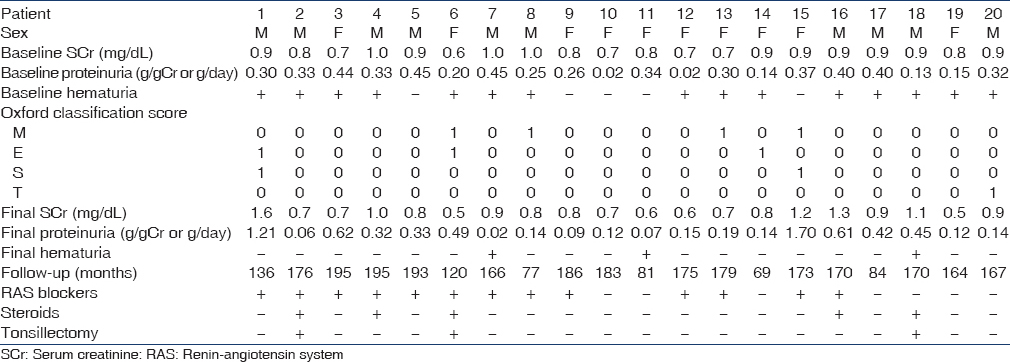

Twenty patients who met the study criteria were selected. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. All patients were Asian, and 50% were male. The median age was 28 (21–34) years. Median BMI was 22.7 (19.6–24.7) kg/m2. Four (20%) patients were classified as overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m2), but none were classified as obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2). Median systolic blood pressure was 120 (112–127) mmHg and median diastolic blood pressure was 70 (61–79) mmHg. All patients had preserved renal function; the median SCr level was 0.90 (0.73–0.90) mg/dl, and the median eGFR was 76.8 (65.2–91.1) mL/min/1.73 m2. The median proteinuria level was 0.31 (0.16–0.39) g/day. In 5 (25%) patients, proteinuria was absent at baseline testing. Furthermore, in 5 (25%) patients, microhematuria was absent at baseline testing. M1 was observed in four patients. E1 was present in three patients. S1 was present in two patients. T1 and T2 were found in one and no patients, respectively.

Follow-up and treatment

The median follow-up duration was 170 (124–182) months. Five (25%) patients received steroid therapy, and three of these patients also underwent a tonsillectomy. A total of 13 (65%) patients received treatment with RAS blockers, either angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists.

Primary outcomes

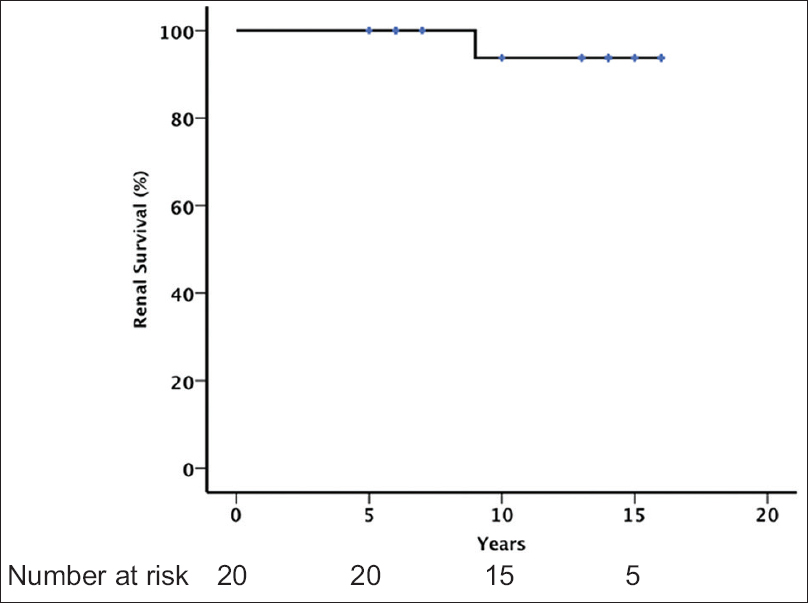

No patient developed ESRD. Only one patient showed a SCr increase of >50% from baseline. The main clinical characteristics of the patient are summarized in Table 2. The patient was a 16-year-old man whose renal biopsy showed M0, E1, S1, and T0. He had a preserved renal function, normal blood pressure, and a minimal proteinuria (0.30 g/day) at presentation. His renal function declined following his initial presentation. RAS blockers were prescribed but he did not receive any steroid therapy. His SCr increased by 50% after 111 months. Renal survival rates (SCr increase <50%) were 100%, 93.8%, and 93.8% after 5, 10, and 15 years of follow-up, respectively [Figure 2]. We were not able to identify any clinical or pathologic risk factors for developing proteinuria >0.5 g/day.

- Renal survival (defined by a status free of >50% increase of serum creatinine from baseline and no end-stage renal disease)

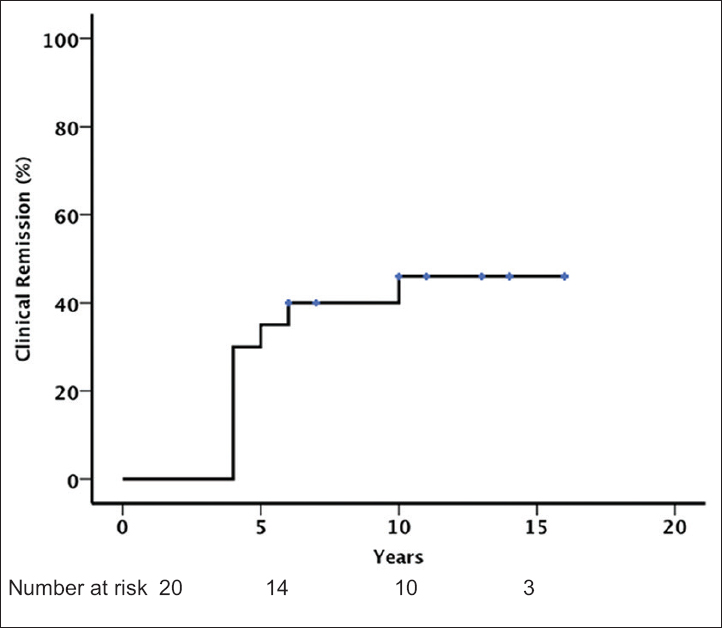

Clinical remission of the disease was observed in 9 (45%) patients [Figure 3]. The median time to remission was 57 months (IQR: 55–68 months). Five of the nine patients who achieved remission did not receive any treatment during follow-up. RAS blockers were prescribed in the remaining four patients, one of whom also received steroid therapy and tonsillectomy. The baseline and final clinical characteristics of all the 20 patients along with Oxford classification are shown in Table 3. The only significant difference between patients with and without remission was a higher proteinuria level at baseline among the patients who did not achieve remission. On univariate Cox analysis, baseline proteinuria was the only factor significantly associated with the absence of remission (hazard ratio = 0.003; 95% confidence interval = 0.00–0.30; P = 0.013).

- Clinical remission (defined by preserved renal function, proteinuria persistently <0.2 g/day, and the persistent disappearance of microscopic hematuria)

Secondary outcomes

Proteinuria >0.5 g/day developed in 4 (20%) patients. All of these patients received RAS blockers and one patient also received steroid therapy. Of those 16 patients who did not develop proteinuria >0.5 g/day, nine patients received RAS blockers. Although the presence of S1 was significantly higher in patients who developed proteinuria >0.5 g/day (P = 0.032), it did not remain as an independent risk factor by univariate analysis. We were not able to identify any clinical or pathologic risk factors for developing proteinuria >0.5 g/day.

Discussion

Information about the long-term outcomes of IgAN patients with benign clinical presentations is scarce. A significant proportion of patients in whom a renal biopsy later establishes the diagnosis of IgAN can present with minor urinary abnormalities. Our study analyzed the long-term outcomes of patients with biopsy-proven IgAN who presented with minor abnormalities (preserved renal function and proteinuria <0.5 g/day). We demonstrated that IgAN patients with clinically benign presentations had a high remission rate. Nine (45%) patients achieved clinical remission as defined by preserved renal function, proteinuria <0.2 g/day, and a disappearance of microhematuria. Only 1 (5%) patients showed a SCr increase of >50%, with no patient developing ESRD.

The previous studies focusing on patient and renal outcomes in biopsy-proven IgAN patients with benign presentation have used various definitions of early IgAN, clinical remission, and renal survival. Among them, two studies using a similar definition with our study have been reported [Table 4]. One is from Europe and the other from Korea.[69] Clinical remission was observed in 45% of our patients, which was similar to that in the European study (38%), but much higher than that in the Korean study (25%). The difference in the remission rate between our study and the Korean study might be explained by the difference in the follow-up duration. More patients might have entered clinical remission with a longer follow-up period as observed in our study. On the other hand, SCr increase >50% with respect to baseline or ESRD was observed in 5% of our patients. Although the Asian origin is reported to be a risk factor for progression to ESRD in IgAN,[14] the rate was similar compared to the European study.

Of the nine patients in our study who achieved clinical remission, five patients received RAS blockers and one patient received steroid therapy in addition to a tonsillectomy. The remaining 4 (44%) patients achieved spontaneous remission. Patients who developed clinical remission had lower baseline proteinuria at presentation. Spontaneous clinical remission of IgAN is a well-known characteristic of the disease, although its precise incidence has not been widely reported.[15] Our study showed that clinical remission is common among IgAN patients with minor abnormalities at presentation.

Our results also confirmed that the level of proteinuria has a significant influence on long-term renal outcomes, even in IgAN patients with minor abnormalities at presentation. On univariate Cox analysis, the baseline proteinuria showed a significant association with the probability of remission. These results are in agreement with many observational and prospective randomized controlled trials that have emphasized the crucial role of proteinuria in the long-term outcome of the disease.[9161718]

The Oxford classification, proposed as a reproducible method for the interpretation and scoring of histologic lesions in IgAN,[121319] has mainly been validated in patients with proteinuria >1 g/day. Information about its application in patients with minor abnormalities is very scarce. Our study also provides interesting data on the histologic characteristics of IgAN patients presenting with minor abnormalities. M1 was the most common finding, observed in 4 (20%) patients. E1 was observed in 3 (15%) patients. S1 and T1 were uncommon lesions and were observed in 2 (10%) patients and 1 (5%) patient, respectively. Contrary to the previous report,[89] we could not find any association between the presence of S1 and poor renal survival or the development of proteinuria >0.5 g/day. This might due to the small sample size and further studies are needed to clarify the applicability of the Oxford classification to IgAN patients presenting with minimal or no proteinuria.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study; second, the sample size was small; third, the presence of a lead-time bias cannot be excluded and fourth, some of the patients received treatment. However, our study has important implications for the clinical management of patients presenting with minor urinary abnormalities. Particular strengths and insights are gained from the long follow-up duration and the histopathology assessment using the Oxford classification in our study. In comparison with the European and Korean studies, our study had a longer median follow-up time. In addition, as far as we know, this is the first study to assess the outcome of Asian patients with IgAN presenting minor abnormalities using the Oxford classification. Further studies are needed to clarify the applicability of the Oxford classification to IgAN patients with minimal or no proteinuria.

Conclusion

Although the renal function can decline in an exceptional case, sustained clinical remission was observed in nearly half of the patients. The long-term prognosis of Japanese IgAN patients presenting with preserved renal function and minimal or no proteinuria can be excellent.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- IgA nephropathy, the most common glomerulonephritis worldwide. A neglected disease in the United States? Am J Med. 1988;84:129-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Japan Renal Biopsy Registry: The first nationwide, web-based, and prospective registry system of renal biopsies in Japan. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2011;15:493-503.

- [Google Scholar]

- How benign is IgA nephropathy with minimal proteinuria? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1607-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term prognosis of clinically early IgA nephropathy is not always favorable. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:94.

- [Google Scholar]

- The natural history of immunoglobulin a nephropathy among patients with hematuria and minimal proteinuria. Am J Med. 2001;110:434-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term outcomes of IgA nephropathy presenting with minimal or no proteinuria. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1753-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical course and prognostic factors of clinical early IgA nephropathy. Neth J Med. 2008;66:242-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. 2009;76:546-56.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: Rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int. 2009;76:534-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Individuals of Pacific Asian origin with IgA nephropathy have an increased risk of progression to end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2013;84:1017-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-standing spontaneous clinical remission and glomerular improvement in primary IgA nephropathy (Berger's disease) Am J Nephrol. 1987;7:440-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term beneficial effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with nephrotic proteinuria. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20:240-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Oxford IgA nephropathy clinicopathological classification is valid for children as well as adults. Kidney Int. 2010;77:921-7.

- [Google Scholar]