Translate this page into:

Multifocal Cryptococcus Neoformans Osteomyelitis in a Kidney Transplant Recipient

Corresponding author: Sanjeev Gulati, Department of Nephrology, Fortis Health Care Limited, New Delhi, India. E-mail: sgulati2002@gmail.com.

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Chauhan S, Gulati S, Naorem GS. Multifocal Cryptococcus Neoformans Osteomyelitis in a Kidney Transplant Recipient. Indian J Nephrol. doi: 10.25259/IJN_2_2024

Abstract

Cryptococcal infections are notoriously difficult to diagnose and have been associated with high morbidity and mortality. Cryptococcus neoformans presenting as osteomyelitis is an unexpected clinical scenario in the transplant ward. A young male who underwent spousal kidney donor transplantation 16 months ago presented with painful and ulcerated soft tissue in upper and lower limbs which were diagnosed as cryptococcus osteomyelitis. He was managed with surgical debridement, liposomal amphotericin B, flucytosine and reduction in maintenance immunosuppression (IS). To our knowledge this is the first reported case of multifocal cryptococcus osteomyelitis in a kidney transplant recipient.

Keywords

Cryptococcus

Osteomyelitis

Transplantation

Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans (CN) is an invasive fungal infection that affects solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients.1 CN infection in SOT has been described as meningitis and pneumonia, but the entity as osteomyelitis is limited to a few case reports in kidney,2,3 lung,4 and liver transplants.5-7 We report multifocal cryptococcus osteomyelitis (CNO) in a kidney transplant (KT) recipient.

Case Report

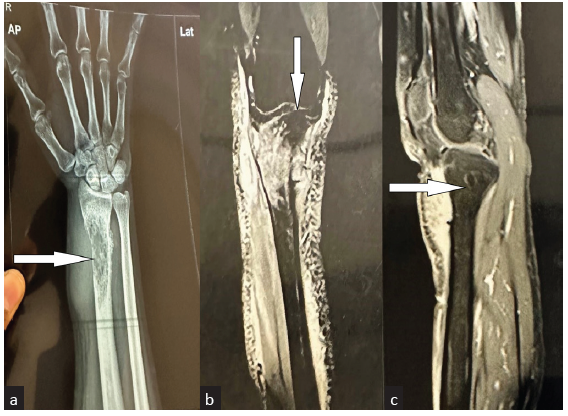

A 35-year-old man underwent ABO compatible living spousal donor KT 16 months back with thymoglobulin induction. His baseline serum creatinine was 1.1 mg/dl (steroid 10 mg once daily, tacrolimus @ 0.1 mg/kg with trough levels of 5 ng/mL, and mycophenolic acid in dose of 25 mg/kg/day). He was in continuation phase of anti-tubercular treatment for extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (isoniazid 150 mg, Rifampicin 450 mg, and ethambutol 800 mg once daily). He also had controlled post-transplant diabetes mellitus. The patient first noticed swelling over his right leg, which progressively increased over 15 days and transformed into a painful tense abscess [Figure 1]. Over the next 2 months, he also noticed localized right fore-arm soft tissue swelling. The swelling was painful, fluctuant, and progressively increasing. As his symptoms did not abate, he visited us nearly 2 months after his symptoms first began. On presentation, his vitals, and general and systemic examination were normal. Initial blood investigations were notable for high C-reactive protein of 71 g/dl. His X-ray right forearm [Figure 2a] showed poorly marginated intramedullary lesion seen in the distal aspect of the radius. Magnetic resonance imaging of the right leg showed infective osteomyelitis [Figure 2b-2c]. Pus sample was aspirated from the right arm wound. The gram stain, acid fast bacilli, nocardia stain, fungal stain, TB culture, MTB gene Xpert, and acid fast bacilli were all negative. In view of the infective osteomyelitis, bone curettage, biopsy, external fixation, and bone cementing were done. Pus aspiration and multiplex polymerase test showed CN growth. Bone biopsy sent for fungal culture and histopathology also revealed CN, for which the patient was started on intravenous liposomal amphotericin B (LAMB) in a dose of 200 mg once daily (5 mg/kg/day) and oral flucytosine (5-FLU) 1250 mg every 6 hours. The baseline immunosuppression was reduced by withdrawing the antimetabolite and halving tacrolimus. During the second week an allograft renal biopsy was done for creeping serum creatinine which showed acute tubular necrosis. His tacrolimus level was 4.4 ng/mL and no further changes were made to immunosuppression. After 1 month, the patient’s clinical condition had improved, and the swelling over his right forearm and right leg had subsided. The renal allograft function was stable and he was discharged on oral fluconazole 150 mg, which was continued for 6 weeks. At 18 weeks, the patient is doing well, with baseline graft function and baseline immunosuppression restored.

- (a) The abscess over the right leg developed insidiously, progressively increased in size, and became painful over 2 months; it was tender to touch and bled intermittently. The patient got it aspirated by a health care practitioner and subsequently it gave way to a nonhealing ulcer. (b) Over the next 2 months, he also noticed another similar abscess developing over his distal forearm, which he got aspirated. The abscess healed with scarring.

- (a) Right hand osteomyelitis: a soft tissue swelling with with bony erosions in the diaphysis, metaphysis regions of radius bone (white arrow). (b) MRI Right knee: Cortical based destructive lesion of the proximal tibia is seen in the region of the tibial tuberosity (white arrow) with a narrow zone of transition and presence of a thin sclerotic rim. It is associated with thick organised phlegmonous collection in the adjacent pretibial subcutaneous space, involving the patellar tendon insertion site and reaching up to the overlying skin. (c) This phlegmonous collection (white arrow) measures approximately 0.8 x 3.5 x 3.6 cm in maximum AP, transverse and craniocaudal dimensions. AP: antero-posterior

Discussion

Nonhealing ulcers are an uncommon problem in KT where infections and malignancies are the predominant causes. CN is a rare invasive fungal infection in SOT with high morbidity, mortality, treatment failure, and relapses.8 Among SOT, the clinical presentation of CN spans a varied spectrum from neurologic to pulmonary symptoms. And, only a few CNO reports have been published in SOT. Per our literature search, we report the first multifocal CNO in a KT. In a recent Swiss multicentric study,9 fungal etiologies represented the least likely etiology of osteomyelitis. In that report, male gender and diabetics are more prone to osteomyelitis which corresponds with our case. In our report, the patient was successfully managed as per the American Society of Transplantation guidelines for infectious disease10 where we have used a combination therapy of LAMB and 5-FU, followed by oral fluconazole as consolidation therapy after extensive debridement of the bone. The various challenges faced were rare clinical diagnosis, morbidity associated with orthopedic surgery, and allograft dysfunction.

Table 1 highlights the snapshot of clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes of previously published CNO in SOT. The highlighting differences in our case are multifocal origin, use of combination therapy, and a concomitant history of tuberculosis. The learning points that are being added for a better understanding of this rare entity is that it affects lower limb axial skeletons predominantly and upper limb involvement is rare. Also, the prolonged duration of therapy is a common factor.

| Author | Country | 2016 | SOT | Years of transplant | Bone involvement | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current case report | India | 35/M | Kidney | 2 years | Right tibia (lower limb) and right radius (upper limb) | Debridement, LAB + Flucytosine + Fluconazole | Alive |

| Shrader A, et al.4 | USA | 11/M | Lung | 2 years | Rib | Flucytosine + Fluconazole | Alive |

| Ghioldi ME, et al.2 | Argentina | 69/F | Kidney | 10 years | Calcaneus | Debridement, LAB for 3 months | Alive |

| Poenaru SM, et al.5 | Canada | 53/M | Liver | 4 years | Patella | Debridement, LAB | Death AKI |

| Pudipeddi AV, et al.6 | Australia | 36/M | Liver | 2 years | Frontal skull | Debridement, LAB | Alive |

| Balaji GG, et al.3 | India | 51/M | Kidney | 12 years | Talus | Debridement, LAB | Alive |

| Lai KK, et al.7 | USA | 55/M | Liver | 2 years | Right tibia | Debridement, LAB | Alive |

| Singh N, et al.10 | USA | 66/M | Liver | 6 years | Left fibula | Fluconazole + flucytosine | Reported outcome of 14 days in hospital only |

USA: United States; M: male; SOT: solid organ transplantation; LAB: liposomal amphotericin B; AKI: acute kidney injury.

In our case, the successful outcome is attributed to a high index of suspicion, extensive laboratory panel availability, and a multi-disciplinary team which are cornerstones for managing such a difficult case.

Conclusion

CNO is extremely rare in a KT and its diagnosis and treatment pose significant challenges by meticulous modification of immunosuppression to minimize the damage to graft function. We suggest clinicians to have a high index of suspicion and practice a thorough investigation profile in all nonhealing ulcers.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- cryptococcosis in solid organ transplantation-guidelines from the american society of transplantation infectious diseases community of practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13543.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryptococcus neoformans osteomyelitis of the calcaneus: Case report and literature review. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211027094.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A rare case of cryptococcal infection of talus with pathological fracture that healed with medical management. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:740-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and treatment of cryptococcal osteomyelitis in a pediatric lung transplant patient. Pediatr Transplant. 2022;26:e14165.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryptococcus neoformans osteomyelitis and intramuscular abscess in a liver transplant patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017221650.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Cryptococcal osteomyelitis of the skull in a liver transplant patient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18:954-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case 19-1999: A 55-year-old man with a destructive bone lesion 17 months after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1981-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: Results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1101-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology and outcomes of bone and joint infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2022;22:3031-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary cryptococcosis in solid organ transplant recipients: Clinical relevance of serum cryptococcal antigen. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:e12-e18.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]