Translate this page into:

Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty of Dysfunctional Hemodialysis Vascular Access: Can Careful Selection of Patients Improve the Outcomes?

Address for correspondence: Dr. Omair A. Shah, 167 Nursingh Garh Karanagar, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir – 190 010, India. E-mail: shahomair133@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Our study aimed to evaluate the role of endovascular intervention in salvaging hemodialysis access in patients of end-stage renal disease with specific attention to features that may predict a poor outcome. We also evaluated the role of ultrasonography (USG) in the management of these patients.

Methods:

Forty-two patients with dysfunctional hemodialysis arteriovenous fistulas (AVF) were taken up for percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) with or without stent placement. All patients underwent a pre- and postprocedural USG Doppler to assess parameters such as mean flow, mean peak systolic velocity, and vessel diameter. Technical and clinical success rates were calculated, and characteristics causing increased failure rates (long-segment and multisite stenosis and diabetes) were noted.

Results:

The most common sites of stenosis were the anastomotic and perianastomotic sites (n = 27, 63%) on the venous side followed by distal venous drainage site (23%) and central venous stenosis (14%). The technical and clinical success rates were 98% and 92%, respectively. Three- and 6-month patency rates were 83% and 71%, respectively. Common characteristics in patients with failure (primary or secondary) were diabetes, increased age, increased length of stenosis (>2cm) and multisite stenosis. USG Doppler parameters showed a significant improvement post-PTA (P < 0.001) indicating clinical success. No major complication was noted in our study.

Conclusion:

PTA is successful for dysfunctional hemodialysis access. Careful selection of patients can improve the success rates and decrease economic burden in a resource-constrained country like ours. USG Doppler is essential in the assessment of iatrogenic hemodialysis AVFs.

Keywords

Arteriovenous fistula

chronic kidney disease

hemodialysis

percutaneous transluminal angioplasty

ultrasonography

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease is a complex disease and requires multidisciplinary management.[1] The answer to this disease at present, short of renal transplant, includes dialysis in the form of either hemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis. Hemodialysis can be done via vascular access in the form of an arteriovenous fistula (AVF), arteriovenous graft (AVG), or a venous catheter. Among these methods, AVF is preferred based on more durability and decreased risk of infections.[2] It is estimated that 60.3% of patients undergoing hemodialysis died within 5 years, 19.0% died within 5 to 10 years, and only 20.7% lived for more than 10 years.[3] The role of a radiologist has now become central in the management of these patients helping in preoperative vascular mapping before surgical AVF creation, its complications, as well as management of those complications. The major issues with vascular access sites for HD include limited durability ranging from 1 to 3 years commonly due to thrombosis or stenosis.[4] A dysfunctional AVF can present in the form of clinical or hemodynamic abnormality, and this occurs in the presence of vascular stenosis causing >50% reduction in the luminal diameter of the blood vessel.[56] Although there are a few sites that can be utilized for a new fistula once one gets dysfunctional, the number of sites can become a shortfall as the life expectancy of the patient increases. Therefore, a way to recanalize these fistulas is required. Percutaneous endovascular radiological management in the form of balloon angioplasty with or without stent placement has emerged as the management of choice with high clinical and technical success rates increasing the durability of the AVFs.[7] This radiological management can have certain complications including venous rupture, hematoma, thrombosis, and so on that can, however, can be well managed radiologically.[89] The cost of the procedure can be a limiting factor especially in developing countries; therefore, careful selection of patients with a good chance of positive outcomes is essential. Our study was aimed to assess the success rates of this endovascular interventional therapeutic procedure. We also assessed preprocedure features that can predict the outcome failed procedure.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a prospective, observational, hospital-based study over the duration of 2 years (2018–2020) including a total of 42 patients. The patients included were those on HD through AVF, who either had a dampened thrill or a lack of pulsatile flow on clinical examination, flow disturbance picked up by dialysis technician, or an outflow vein stenosis (diagnosed on Doppler). We excluded patients with blood coagulation disorder, sepsis or active infection, metastatic cancer or other terminal medical condition with limited life expectancy (<6 months), allergy to iodinated contrast media or heparin, and pregnant patients.

The dysfunction of hemodialysis was confirmed by ultrasonography (USG) Doppler analysis prior to angioplasty in the form of significant stenosis (>50%), decreased flow volume in the draining vein (<250 mL/minute), and/or a peak systolic velocity (PSV) ratio of ≥3 (PSV at stenotic site/ PSV in distal draining vein). All the USG Doppler examinations were done using the GE LogiqP5 machine equipped with both a linear probe (6–13MHz) and a curvilinear probe (3–5MHz) along with a sterile wrap. The assessment was done just before the procedure and 24 to 72 hours after the procedure by the same radiologist having experience of more than 5 years in Doppler assessment using the same Doppler parameters and a comparison of Doppler indices pre- and postprocedure was made. Any postprocedure complication was also documented using USG.

After confirming the fistula dysfunction and the culprit lesion, a plan for angioplasty with or without stent placement was chalked out. Informed consent was taken from all the patients, and all the procedures were done in our interventional lab using digital subtraction angiography (DSA) guidance (Siemens Artis zee). The patients were started on prophylactic antibiotics and anticoagulation in the form of heparin (in consultation with the nephrologist and a hematologist). This anticoagulation was given in patients with thrombosis and also helped lower postangioplasty thrombosis events. Antibiotics are generally given for a few days at our center to cover for any lapse in antisepsis that can be disastrous. The fistula was accessed retrograde, anterograde, or dual depending on the anatomy and location of the stenosis. Under DSA guidance, a preprocedural fistulogram was obtained using iodinated contrast (Omnipaque/Contrapaque 300 mg/mL) identifying the site of stenosis, and with an angled-tip hydrophilic guidewire, the stenotic lesion was crossed and procedure was completed. Check angiogram was immediately performed after PTA, and the procedure was considered successful if there was <30% residual stenosis. After obtaining a satisfactory result, the sheath was removed, and gentle pressure dressing was applied, and the patients were discharged after a brief period of observation.

A postprocedural USG Doppler was performed 24 to 48 hours after the angioplasty, and the functional success was confirmed (i.e., an increase in the flow volume of the draining vein of >400 mL/minute, a decrease in PSV ratio of <2). The patients were followed up over a period of 8 to 12 months confirming the success or failure of the procedure.

Statistical methods

The recorded data were exported to the data editor of SPSS, Version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and the categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. A paired t test was employed for comparing hemodynamic parameters before and after angioplasty. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All P values were two tailed.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients

In our study, we evaluated a total of 42 patients with a mean age of 53.34 ± 18.46 years and male 26 (62%). In our study, 57% (n = 24) of patients had radiocephalic AVF, 29% (n = 12) had brachiocephalic AVF, and 14% (n = 6) of patients had brachiobasalic AVF. Our patients had a fistula on the left side in 33 (79%) patients, and on right side in the remaining nine (21%) patients. We had 13 (31%) patients presenting with inadequate flow across AVF, 11 (26%) patients with inadequate flow with limb edema, eight (19%) patients had inadequate flow with difficult cannulation (six out of 26 patients), and 10 (24%) patients with inadequate flow with decreased thrill. Prolonged bleeding after access puncture was not seen in any of our patients.

Stenosis

In our study, the predominant site of stenosis was the draining vein followed by the anastomosis, whereas no arterial side stenosis was noted. Ten (23%) patients had anastomotic stenosis, 17 (40%) had perianastomotic venous stenosis (within 4 cm of anastomotic site), 10 (23%) had distal venous stenosis (>4 cm distal to fistula site), and five (14%) had central stenosis. Also, the majority of our patients had a single stenotic lesion (n = 39, 93%), whereas three (7%) others had two or more stenosis. Majority of our patients (n = 36, 86%) had a short-segment stenosis (<2 cm), whereas the rest (n = 6, 14%) had long-segment stenosis.

Radiological Procedures

USG was able to detect the culprit stenosis in 37 (88%) patients, whereas no stenosis was identified in five (12%) patients. Preprocedural mean flow volume in draining veins was 210.2 ± 63 mL/minute (140–265 mL), mean PSV of draining vein was 365.4 ± 62.25 cm/second (180–450 cm/second), and mean diameter of draining vein was 4.33 ± 0.768 mm (2–5 mm). DSA was able to identify the culprit stenosis in all of our patients and helped classify them as long or short segment as well as perianastomotic or distal to the anastomosis. Additional stenotic lesions were present in five (12%) patients when compared with USG findings. Therefore, diagnostic venogram was superior to ultrasonography in detecting additional stenotic lesions particularly central venous stenosis. In our study, while all patients had technical success on PTA, anatomic success was not achieved in five (12%) patients [Table 1]. In view of the restenosis/resistant stenosis seen at DSA, stent placement was needed in four (10%) patients with central venous stenosis.

| Intraprocedural | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Technical success | 41 | 98 |

| Anatomical success | 37 | 88 |

Complications

The complications in our study postangioplasty included minor complications (pain and hemorrhage) in 15 (36%) patients, the perivascular hematoma was seen in four patients (9.5%), and four patients (9.5%) had thrombosis postprocedure. One patient was having complete thrombosis, whereas three had partial thrombosis. Aneurysm or pseudoaneurysm was not seen.

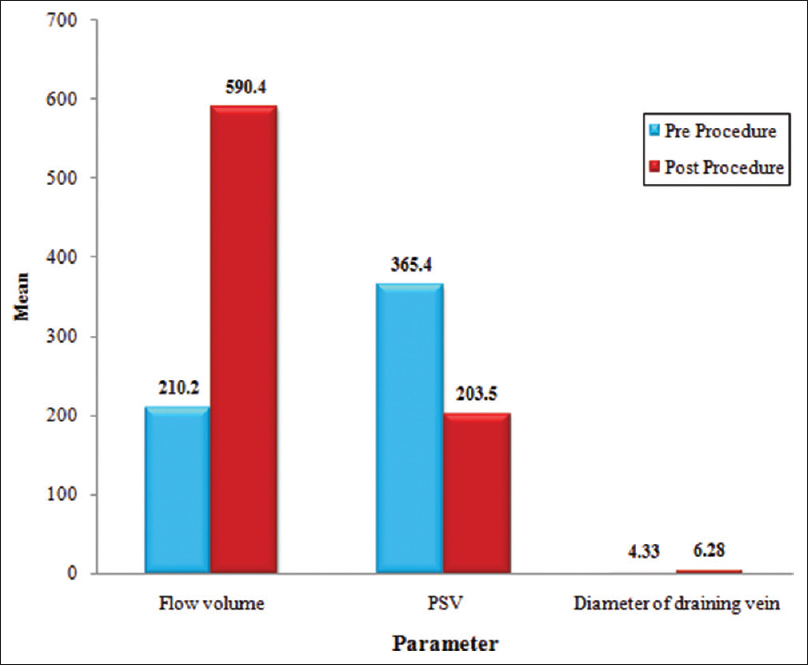

Postprocedural USG

The postprocedural evaluation was done 24 to 72 hours after the intervention. Postprocedural mean flow volume in draining vein was 590.4 ± 148.5 mL/minute (240–685), mean PSV of draining vein was 203.5 ± 53.02 cm/second (110–300), and mean diameter of draining vein was 6.2 ± 0.938 mm (4–8). A comparison between the pre- and postprocedural values was done showing a statistically significant improvement in all three parameters [Table 2, Figure 1].

| Parameter | Preprocedure | Postprocedure | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Flow volume (mL/minute) | 210.2 | 63.23 | 590.4 | 148.5 | <0.001* |

| PSV (cm/second) | 365.4 | 62.25 | 203.5 | 53.02 | <0.001* |

| Diameter of draining vein (mm) | 4.33 | 0.768 | 6.28 | 0.938 | <0.001* |

- Bar diagram showing the comparison of hemodynamic parameters before and after angioplasty

Primary patency rate at 3 and 6 months

In our study, at 3 months of follow-up, 83% (n = 31 out of 37 with anatomic success) of patients had patent AVF, whereas the same figure at 6 months was 71% (n = 26).

Characteristics indicating poor outcome

We found diabetes (n = 13, 81%), long-segment stenosis (n = 5, 31%), multisite stenosis (n = 3, 19%), and failure of complete inflation of angioplasty balloon (n = 10, 62%) as important characteristics predicting poor outcome at 6 months postangioplasty in our patients. The difference in these characteristics when compared with those with good outcomes was found to be statistically significant [Table 3].

| Characteristics | Patency at 6 months | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present (n=26) | Absent (n=16) | ||

| Diabetes | 6 (23%) | 13 (81%) | 0.003 |

| Long-segment stenosis (>2 cm) | 1 (4%) | 5 (31%) | 0.001 |

| Multisite stenosis | none | 3 (19%) | <0.001 |

| Failure of balloon waist removal | 2 (8%) | 10 (62%) | <0.001 |

Discussion

We conducted a study to assess the efficacy of angioplasty in salvaging dysfunctional AVFs in patients requiring hemodialysis and included a total of 42 patients with 26 males and 16 females. The mean age of the patients was 53.34 ± 18.46 years. The number of patients, although limited, was comparable with studies done by Higashiura et al.,[10] Kimand Cho[11] Scaffaro et al.,[12] and Gorin et al.[13] The mean age is expected as most of the younger patients usually find a transplant; however, in the transit time, younger patients with AVF are less likely to suffer from fistula failure than older patients.[14]

The most common type of fistula in our study was the radiocephalic variant followed by brachiocephalic and brachiobasilic ones. Also, most of the fistulas were on the nondominant left side except few that were either redo procedures or were done in patients with left dominance. Although this preference varies from one institution to other, there is an overall preference for the radiocephalic variant as is shown by Gjorgjievski et al.[15] and Weale et al.[16] in their studies. Radiocephalic fistula is the preferred site for initial fistula formation although it is associated with higher failure rates because it requires less frequent superficialization and may dilate the more proximal veins to enable easier fistula creation in the future if required.

The most common site of stenosis in our study was the anastomotic and perianastomotic sites on the venous sites followed by the distal venous drainage site and central venous stenosis. One of our patients with central venous stenosis had a history of prior central venous catheter placement and another with permanent pacemaker placement placed in the periphery. Pacemaker placement on the same side of the AVF should, however, be avoided. Thus, the most common lesion resulting in primary failure is an acquired juxta-anastomotic stenotic lesion. These results are quite similar to those of Badero et al.[17] The juxta-anastomotic site is commonly involved in stenosis in view of the intimal hyperplasia that occurs in response to increased flows, while the arterial and distal venous site stenosis may be associated with puncture site inflammatory reaction. The majority of our patients (92.3%) had only one stenotic lesion, and only 7.7% of patients had more than one stenotic lesion. This is probably because most multisite stenotic lesions respond poorly to angioplasty management and are, therefore, less likely to be referred for endovascular intervention to a radiologist or interventional nephrologist than a surgeon for a redo procedure. This is probably owing to the endovascular management being a new modality not known to all and the traditional redo procedures common with the surgeons. The length of stenosis can be an important factor in determining the success of angioplasty. In our study, most of the patients (86%) had short-segment stenosis (<2 cm), whereas long-segment stenosis (>2 cm) was seen in the remaining. We tried to study any effect of the length of stenosis on the success rates of the angioplasty procedure and found that long-segment stenosis is more likely to fail angioplasty treatment compared with short-segment stenosis.

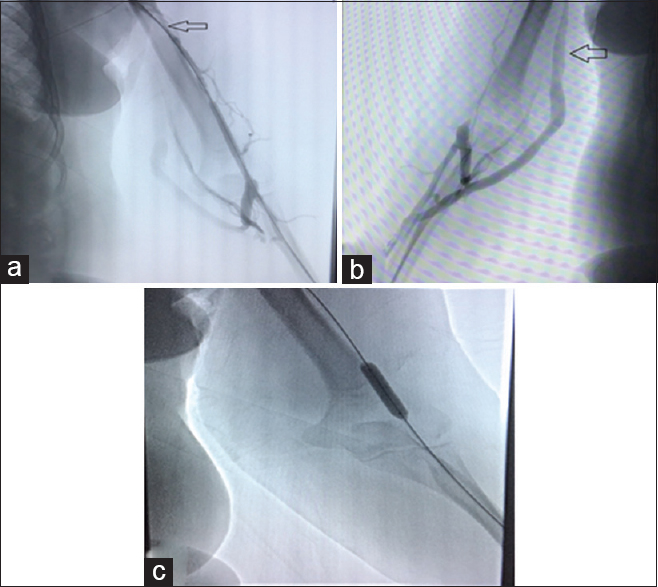

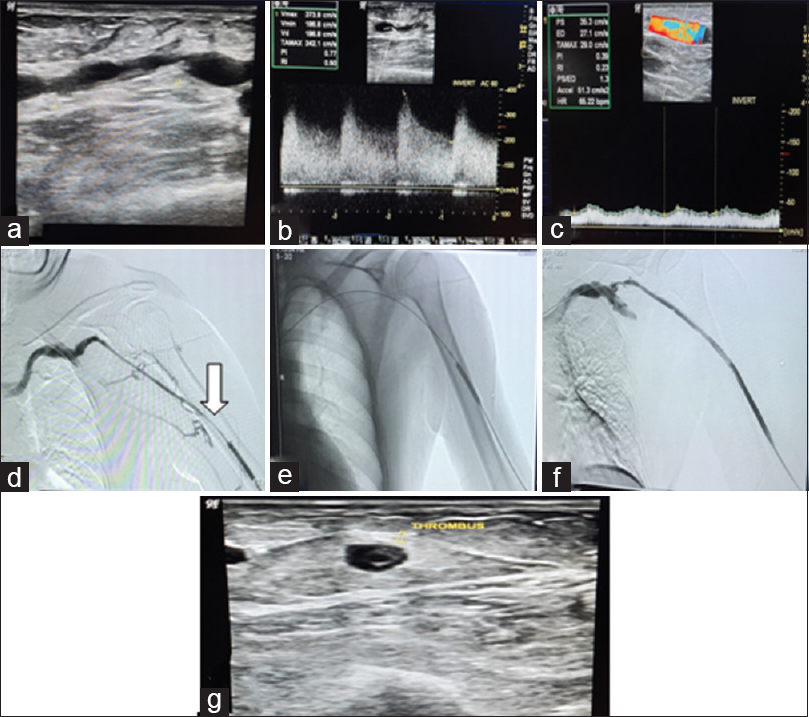

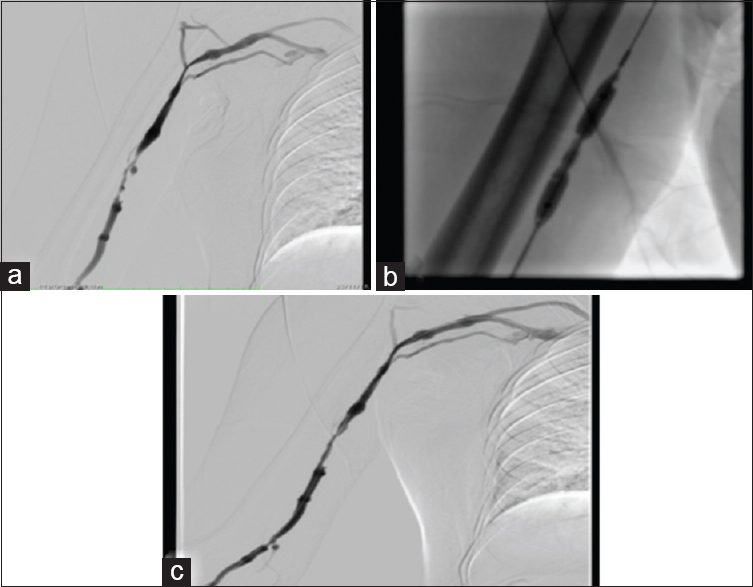

All our patients underwent a balloon angioplasty session at our institution with four (10%) patients requiring stent placement. The procedure was performed under antibiotic and heparin cover using balloons with maximum pressure up to 10 to 12 atms for 90 to 150 seconds. The endpoint of the procedure was when no waist was seen in the contrast-inflated balloon. The success of the procedure was assessed both during the procedure in the form of residual stenosis <30% as well as immediately postprocedure (24–72 hours) in the form of Doppler parameters [Figures 2 and 3]. The technical success in our study was 98% with only one patient in whom we were unable to cross the stenosis with the guidewire. The clinical success of the procedure in our study was around 92%, which was confirmed both on DSA in the form of opening of the stenosis and by Doppler indices in the form of increased mean flow rate and decreased mean PSV and stenosis. Our success rates are more or less similar to many previous studies including those of Irani et al.,[18] Forauer et al.,[19] Aktas et al.,[20] and Machado et al.[21] In these studies and many others, the technical and anatomic/clinical success varied between 75% and 100%. This is probably because of the varying expertise of the interventionist, the characteristics of the study group (age, diabetic), and also the nature of the stenosis (long vs. short segment, single vs. multisite). In our study, we found that patients (n = 5) with failure of the procedure had one or more of the following characteristics: long-segment stenosis (n = 4, 80%) [Figure 4], multisite stenosis (n = 4, 80%) [Figure 5], diabetes (n = 5, 100%), and age >68 years (n = 5, 100%). These findings are in concordance with the previous studies done by Higashiura et al.,[10] Neuen et al.,[22] and Wu et al.[23] The patency rates of those treated successfully in our study were 83% and 71% at 3 and 6 months, respectively. The patients who suffered restenosis also showed certain characteristics in the form of long-segment stenosis, diabetes, and failure to completely remove the balloon waist despite maximum pressure. These patency rates are quite similar to that of Özkan et al.[24] Based on our findings, we believe that patients who are diabetic with long-segment or multisite stenosis and with failure to completely inflate the balloon on PTA should be given the option of redo surgery especially in a resource constraint developing countries like ours, where the cost of endovascular treatment can be a limiting factor. Also, while treating multisite stenosis, the proximal disease should be targeted first followed by the distal one. Therefore, a careful selection of patients can increase the success rates and reduce the economic burden on an already drained-out patient.

![Left brachiobasilic AVF with left upper limb edema (a). DSA angiogram was taken (b) showing severe subclavian vein stenosis (arrow) with multiple venous collaterals (COL). Balloon angioplasty was attempted,however there was waist on balloon[resistant stenosis] (c). Post angioplasty angiogram showed significant residual stenosis(>30%) (d). Self expandable metallic stent (ST) was then deployed across the stenosis with the waist persistent (arrow), however final angiogram (e and f) showed minimal (<30%) stenosis wit no opacification of venous collaterals. P- Pacemaker apparatus](/content/170/2022/32/3/img/IJN-32-233-g002.png)

- Left brachiobasilic AVF with left upper limb edema (a). DSA angiogram was taken (b) showing severe subclavian vein stenosis (arrow) with multiple venous collaterals (COL). Balloon angioplasty was attempted,however there was waist on balloon[resistant stenosis] (c). Post angioplasty angiogram showed significant residual stenosis(>30%) (d). Self expandable metallic stent (ST) was then deployed across the stenosis with the waist persistent (arrow), however final angiogram (e and f) showed minimal (<30%) stenosis wit no opacification of venous collaterals. P- Pacemaker apparatus

- A 59 year old male patient on HD via a brachio-cephalic fistula showing a narrowing of the draining vein (arrow in a). USG (not shown) showed increased PSV and aliasing at the site of stenosis. The patient underwent a session of balloon dilatation (c) with complete inflation of the balloon and no waist. Post PTA angiogram (b) showing no evidence of any residual stenosis

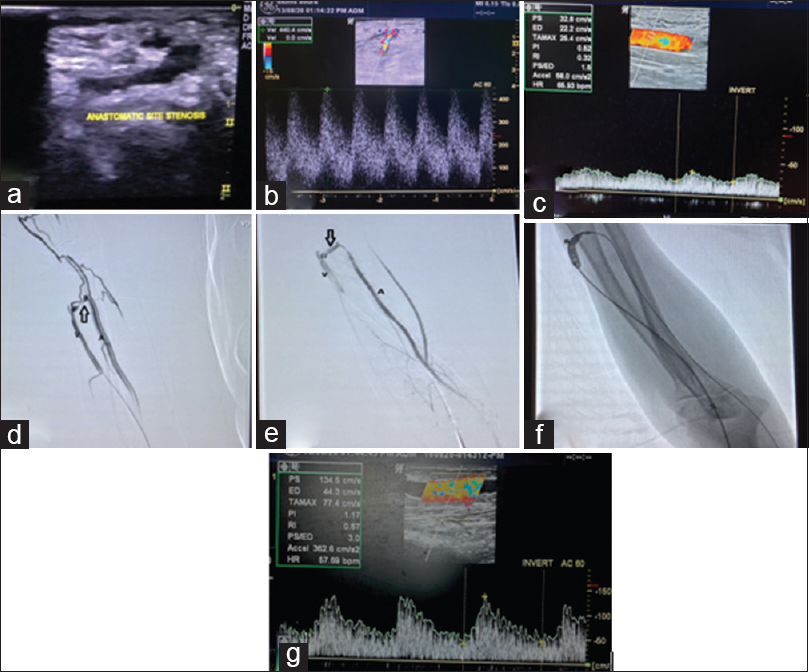

- Left brachiocephalic AVF with decreased thrill. Long segment stenosis in draining was seen on USG (a) with aliasing and high PSV (373.8cm/s) at stenotic site (b) and inadequate flow in draining vein (app. 110 ml/min) (c).DSA venogram confirming the long segment stenotic site (>4 cm) (arrow in d). Balloon angioplasty was done at multiple sites (e). Final angiogram after PTA showing no residual stenosis (f). Partial thrombosis of draining vein (g) was seen on the immediate USG after procedure (24 hours) which progressed to complete thrombosis causing failure

- 65 year old male on hemodialysis via radio-cephalic fistula presenting with decreased thrill with difficult cannulation. USG (not shown) revealed multi site narrowing's of distal draining vein. DSA venogram obtained after gaining vascular access (a) reveals multi site venous narrowing's both short and long segment. Multiple balloon dilations (b) were attempted however a waist was observed each time suggesting a resistant stenosis. Post PTA DSA venogram (c) showing persistence of the stenosis at multiple sites indicating failure

Five of our patients had a central venous stenotic lesion detected on venography mostly secondary to central venous line or pacemaker placement. These lesions were resistant to balloon angioplasty, and 4 (80%) had a residual post-PTA stenosis [Figure 6]. In these four patients, a self-expandable stent was placed in the same or the second setting with good patency rates of 75% at 6 months. One of the patients with central stent placement developed stent thrombosis 3 months post placement and died due to an underlying heart condition. Although the number of patients with the stent is quite small, our results were in concordance with the previous studies including those of Morinière et al.[25] and Bhatia et al.[26] Thus, stent placement is an effective option in cases with central stenosis, especially those resistant to PTA.

- Left distal RC AVF referred in view of inadequate flow with decreased thrill. Anastomotic site stenosis was seen on screening USG (a) with aliasing and high PSV (440cm/s) at stenotic site (b) and inadequate flow in draining vein (app. 150 ml/min) (c). DSA Venogram confirming the stenotic site (arrow in d). Angioplastic balloon was then placed across the stenosis and fully inflated (e) and final angiogram was obtained after PTA with no residual stenosis (arrow in f). Follow up USG showing adequate flow in draining vein (app. 550 ml/min) (g). V-draining Vein, A- Supplying Artery

The role of USG has been studied previously not only in the diagnosis of dysfunctional fistula but also in the objective assessment of angioplasty success. We found that patients with dysfunctional fistulas had a mean flow volume in draining veins of 210.2 ± 63 mL/minute, mean PSV of draining vein of 365.4 ± 62.25 cm/second, and mean diameter of draining vein of 4.33 ± 0.768 mm. We also observed the stenosis in 88% of the patients. The difficulty in identifying the culprit stenosis was more for centrally placed lesions. We observed a significant change in the Doppler parameters post angioplasty [Table 1, Figure 4]. These findings are quite similar to the previous studies done by Nassar et al.[27] and Hingorani et al.[28] who found USG Doppler parameters as effective measurements for PTA success. Also, in patients with failure, USG was able to identify thrombosis of the anastomosis or draining vein in three out of five patients (60%). Thus, USG should be considered at regular intervals in patients with an AVF not only to diagnose dysfunction but also to assess the effectiveness of any interventional procedure. We, therefore, recommend the use of Doppler USG for the initial assessment of AVF failure; however, in cases where USG is not able to identify the culprit lesion, DSA should be done with or without angioplasty.

The complications we encountered were minor and included pain and minor hemorrhage in 15 patients, which were managed conservatively. Four patients had a perivascular hematoma managed conservatively in all, and four others developed thrombosis (three partial and one complete). The patients with thrombosis were managed with anticoagulation, but two of them required a redo surgery owing to the failure of recanalization. No aneurysms or pseudoaneurysms were observed in our study probably due to the use of USG guidance for access puncture as well as lack of cutting balloons associated with high rates of venous rupture.

The limitations of our study included the fewer number of patients in comparison with other previous studies. This is mainly because PTA is a new modality that is being used in our part of the world. Our study did not use cutting balloons and drug-eluting stents, which are being commonly used in other parts of the world with somewhat better results.

Conclusions

PTA is an effective treatment modality for dysfunctional AVFs with high technical and clinical success rates. PTA should be used with caution in patients with diabetes having long-segment and multisite stenotic lesions especially in a resource-constrained environment like ours. USG with Doppler is a sine qua non in AVF assessment both prior and after the PTA and provides objective measurable parameters to document the success of the endovascular procedure.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Nephrology and CVTS, Sheri Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, for their help with this study.

References

- Chronic kidney disease and its complications? Prim Care. 2008;35:329-vii. doi: 10.1016/j. pop. 2008.01.008

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in hemodialysis fistula. Int J Vasc Med. 2018;2018:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of self-reported prognostic expectations of people undergoing dialysis: United States renal data system study of treatment preferences (USTATE) JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1325-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommended standards for reports dealing with arteriovenous hemodialysis accesses. J VascSurg. 2002;35:603-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effectiveness and safety of dialysis vascular access procedures performed by interventional nephrologists. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1622-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in arteriovenous fistulas: Current practice and future developments. J Radiol Nurs. 2017;36:145-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Society of interventional radiology clinical practice guidelines? J VascInterv Radiol. 2003;14:S199-202. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi. 0000094584.83406.3e

- [Google Scholar]

- Balloon catheter dilatation in patients with failing arteriovenous fistulas. Surgery. 1981;89:439-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with secondary functional patency after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of the early failing or immature hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:34-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasonography-guided balloon angioplasty in an autogenous arteriovenous fistula: Preliminary results. Ultrasonography. 2007;26:129-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maintenance of hemodialysis arteriovenous fistulas by an interventional strategy: Clinical and duplex ultrasonographic surveillance followed by transluminal angioplasty. JUltrasound Med. 2009;28:1159-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound-guided angioplasty of autogenous arteriovenous fistulas in the office setting. J VascSurg. 2012;55:1701-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arteriovenous fistula for the 80 years and older patients on hemodialysis: Is it worth it? HemodialInt. 2013;17:594-601.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary failure of the arteriovenous fistula in patients with chronic kidney disease stage 4/5. Open Access Maced J MedSci. 2019;7:1782-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Radiocephalic and brachiocephalic arteriovenous fistula outcomes in the elderly. J VascSurg. 2008;47:144-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Frequency of swing-segment stenosis in referred dialysis patients with angiographically documented lesions. AmJKidney Dis. 2008;51:93-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula and graft stenoses: Randomized trial comparing drug-eluting balloon angioplasty with conventional angioplasty. J Vasc IntervRadiol. 2018;289:238-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dialysis access venous stenoses: Treatment with balloon angioplasty—1- versus 3- minute inflation times. Radiology. 2008;249:375-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty in stenosis of native hemodialysis arteriovenous fistulas: Technical success and analysis of factors affecting postprocedural fistula patency. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2015;21:160-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Results of endovascular procedures performed in dysfunctional arteriovenous accesses for haemodialysis. Port J Nephrol Hypert. 2012;26:266-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with patency following angioplasty of hemodialysis fistulae. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;25:1419-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Baseline plasma glycemic profiles but not inflammatory biomarkers predict symptomatic restenosis after angioplasty of arteriovenous fistulas in patients with hemodialysis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:598-600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular stent placement of juxtaanastomotic stenosis in native arteriovenous fistula after unsuccessful balloon angioplasty. Iran J Radiol. 2013;10:133-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Percutaneous recanalization of occlusion of central and proximal veins in chronic hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 1997;52:1406-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of surgical bypass and percutaneous balloon dilatation with primary stent placement in the treatment of central venous obstruction in the dialysis patient: One-year follow-up. Ann VascSurg. 1996;10:452-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endovascular treatment of the “failing to mature” arteriovenous fistula. Clin J AmSoc Nephrol. 2006;1:275-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of reintervention for failing upper-extremity arteriovenous autogenous access for hemodialysis. J VascSurg. 2001;34:1004-9.

- [Google Scholar]