Translate this page into:

Strongyloid Hyperinfection in a Patient with Immunocompromised Chronic Kidney Disease

Address for correspondence: Dr. S. Hedau, Care Hospitals, Road No. 1, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad - 500 028, Telangana, India. E-mail: santoshhedau@live.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Strongyloid hyperinfection is seen in immunocompromised individuals with underlying lung disease. The use of immunosuppressive drugs is an important risk factor. We report a case of IgA nephropathy with crescent, started on glucocorticoid and mycophenolate mofetil. He presented with bilateral lung opacities with breathlessness. As the breathlessness was not improving, despite adequate ultrafiltration, bronchoscopy was done. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid examination showed the presence of strongyloid larvae, which was later demonstrated in stool also. He responded to antihelminthic treatment with disappearance of larvae from stool but later developed secondary bacterial infections.

Keywords

CKD

pulmonary strongyloidiasis

strongyloid hyperinfection

Introduction

Strongyloid stercoralis is often considered a disease of tropical and subtropical areas, though endemic foci are also seen in temperate regions.[1] The parasite is mostly confined to the tropics and subtropics infecting about 100 million people in about seventy countries.[2] Hyperinfection syndrome is not exactly defined, but the hallmark is an increase in the number of larvae in the stool and/or sputum along with manifestations confined to respiratory and gastrointestinal systems along with peritoneum.[3] Hyperinfection syndrome is estimated to happen in 1.5%–2.5% of the patients with strongyloidiasis.[4]

Case Report

A 69-year-old male, a known case of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease (CKD), presented to emergency room (ER) with fever, shortness of breath (SOB), and gross fluid overload. He underwent renal biopsy 4 months back due to rapid worsening of renal parameters (creatinine 4 mg/dl). He was started on immunosuppression (prednisolone and mycophenolate) in view of cresenteric IgA nephropathy on biopsy. He had rapid worsening of renal parameters (creatinine 7 mg/dl) despite 4 months of immunosuppression and initiated on hemodialysis through the right internal jugular vein access. In the next 3 weeks, dialysis was not done and he developed fluid overload.

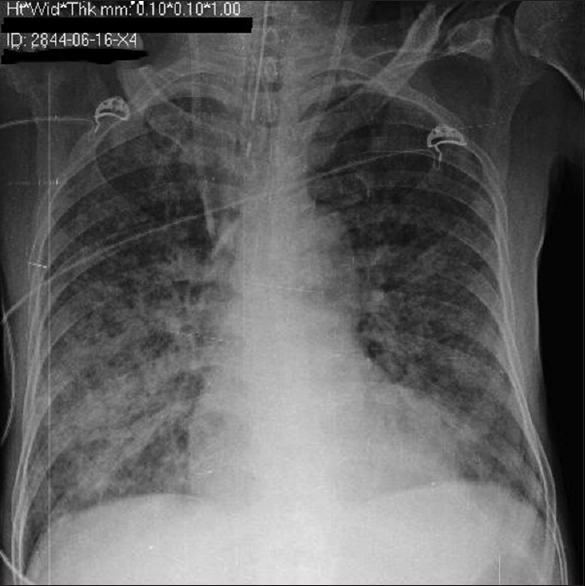

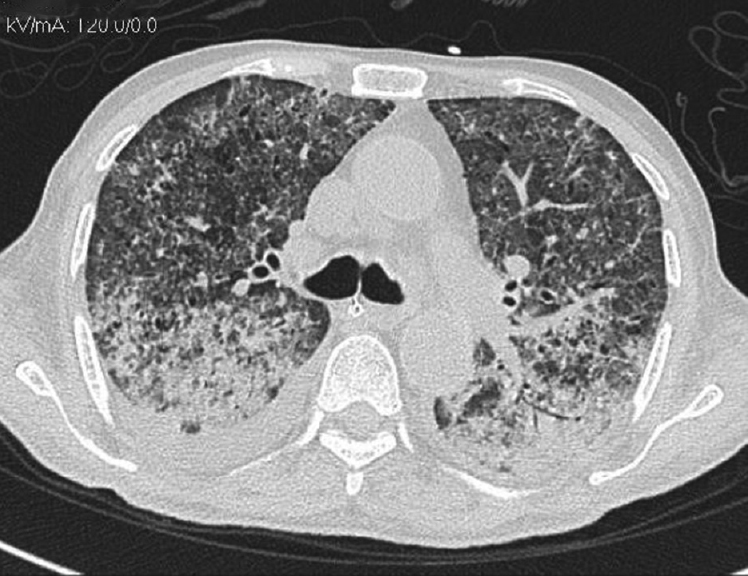

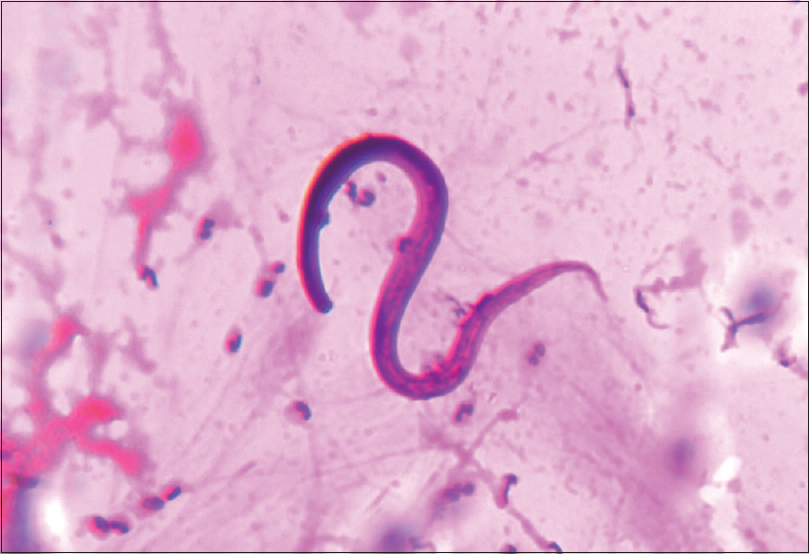

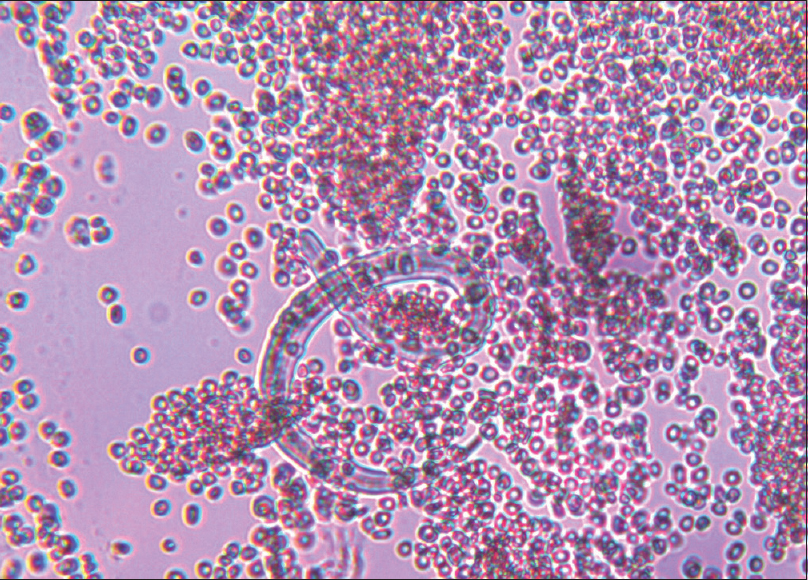

He presented to ER with fever, SOB, and gross fluid overload. On admission, heart rate was 96/min, respiratory rate was 30/min, and SpO2 was 94%, with 10 liter/min oxygen supplement. His complete blood count revealed anemia with no leukocytosis or eosinophilia. Renal parameters were grossly deranged (urea: 203 mg/dl and creatinine: 6.3 mg/dl). Arterial blood gas showed severe metabolic acidosis (pH 7.29, HCO3 11.9). There was severe hypoalbuminemia (serum albumin: 1.7 g/dl). His chest X-ray showed bilateral diffuse opacities [Figure 1]. His oxygenation was not improving despite adequate dialysis and decongestion. Computed tomography scan of the chest revealed bilateral fluffy opacities involving the lower and middle lobes [Figure 2]. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid showed strongyloid larvae [Figure 3]. Subsequently, stool examination also revealed the presence of strongyloid larvae [Figure 4]. BAL culture was sterile. Blood culture showed Escherichia coli growth. He was started on ivermectin 9 mg and albendazole 200 mg once daily along with meropenem for blood stream infection. Strongyloid larvae became undetectable after 7 days of treatment, and serial chest X-ray showed gradual improvement. Subsequently, he developed right lung consolidation, and repeat blood culture showed Chryseomonas growth. The patient remained sick and ventilator dependent. He finally succumbed to secondary bacterial infection after 2 weeks of admission.

- Chest X-ray showing bilateral diffuse opacities

- Computed tomography chest showing bilateral fluffy opacities predominantly in the lower and middle lobes

- Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid showing strongyloid larvae

- Stool examination showing strongyloid larvae

Discussion

The life cycle of Strongyloides stercoralis is distributed between the free-living and parasitic cycles.[3] S. stercoralis is a soil-dwelling nematode and may take one of the two cycles depending on the prevalent conditions and turns parasitic in adverse conditions.[3] The free-living cycle begins with the passage of the rhabditiform larvae in the stool, which, on reaching the soil, molt under favorable conditions to become adult-free living worms. These worms reproduce sexually and produce rhabditiform larvae in turn, which then molt into filariform larvae. The latter forms infect the human host.[3] When a susceptible host is available, the infective filariform larvae penetrate the intact skin, travel to the blood stream through subcutaneous lymphatics, and reach the pulmonary circulation.

Autoinfection is one of the important characteristic features of the life cycle of S. stercoralis. The various life cycle changes in the case of autoinfection are the rhabditiform larvae instead of being shed in the stool molt twice in the body of the host (mainly in the intestine) to become filariform larvae that then penetrate the intestinal wall or perianal skin and reach different organs of the body leading to hyperinfection syndrome if limited to respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts or disseminated infection with involvement of other organ systems.[3]

The hyperinfection syndrome happens from the enormous multiplication and migration of infective larvae, especially in an immunosuppressed state.

Corticosteroids, endogenous as well as exogenous, have been shown to affect the immunity by increasing the apoptosis of Th2 cells, reducing the eosinophil count and inhibiting the mast cell response, thereby leading to hyperinfection or disseminated infection.[1] It is also proposed that both exogenous and endogenous corticosteroids increase steroid-like substances (naturally occurring sterols with nonhormonal anabolic effects) in the body, mainly in the intestinal wall. These substances act as molting signals and lead to increased production of autoinfective filariform larvae leading to hyperinfection and disseminated infection.[56]

The mortality from disseminated infection could be up to 87%.[157] The high mortality rate associated with hyperinfection syndrome and disseminated disease is frequently due to secondary bacterial infections.[8]

For this reason, various authors suggested that steroid-treated patients with chronic lung disease or suspected malignant tumors should be screened for strongyloides infection.[9] Sputum cytology may be the most useful screening procedure,[10] and a BAL may be done to identify the organism in case the sputum is negative for larvae. Although it is a potentially lethal iatrogenic opportunistic infection, it is amenable to treatment with antihelminthic agents if recognized in time. This case illustrates the need to suspect opportunistic pulmonary strongyloidiasis when a patient has immunosuppressed state due to underlying CKD, malnutrition, and exposure to immunosuppressive drugs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Clinical and epidemiologic features of strongyloidiasis. A prospective study in rural Tennessee. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1257-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical features of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in an endemic area of the United States. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:1481-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloides stercoralis. In: Blaser MJ, ed. Textbook of Infections of Gastrointestinal Tract (2nd ed). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002. p. :1113-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloidiasis. In: Guerrant RL, ed. Textbook of Tropical Infections Diseases: Principles, Pathogens, and Practice (2nd ed). Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. :1274-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Complicated and fatal Strongyloides infection in Canadians: Risk factors, diagnosis and management. CMAJ. 2004;171:479-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial complications of strongyloidiasis: Streptococcus bovis meningitis. South Med J. 1999;92:728-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloidiasis of respiratory tract presenting as “asthma”. Br Med J. 1973;2:153-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of pulmonary strongyloidiasis by sputum cytology: A case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1993;36:489-91.

- [Google Scholar]