Translate this page into:

The First ABO Incompatible Kidney Transplantation without Splenectomy in India – A Review at 12 Years

Address for correspondence: Dr. Santosh Varughese, Department of Nephrology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu - 632 004, India. E-mail: santosh@cmcvellore.ac.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Dear Editor,

Non-availability of a blood-group compatible related donor used to be a major barrier to kidney transplantation previously. Today, the world over, ABO-incompatible (ABOi) kidney transplantation has become commonplace. We look back at the first successful ABOi kidney transplantation without splenectomy done over 12 years ago on April 23, 2009. The first ABOi kidney transplantation in India was done successfully at Christian Medical College Vellore on April 23, 2009 without splenectomy. ABOi kidney transplantations are performed more often today[1-3] all over India.

ABOi transplantation had previously been considered an “unwise” prospect.[4] A 21-year-old male, a native of Vellore, Tamil Nadu, presented to us in mid-October 2008 with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 5, the serum creatinine was 20 mg/dl, and ultrasonography revealed shrunken kidneys. He was commenced on hemodialysis, and a left radio cephalic arterio-venous fistula was subsequently constructed. He desired kidney transplantation from his 42-year-old mother, the only prospective related donor. However, his blood group was O Rh-positive while his mother was A Rh-positive. Following counseling regarding the potential additional risks of ABOi transplantation, the patient and his family remained keen for an across ABO barrier transplantation.

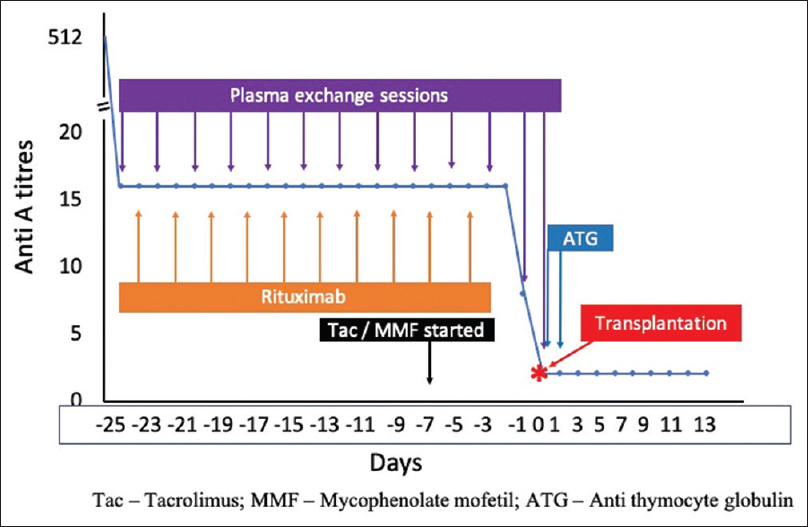

The patient was HLA haploidentical with his mother, with no detectable anti-HLA antibodies. The baseline anti-A titer (Coombs) was 1:512. The desensitization protocol included the following: for 14 days, the patient received 3 L of plasma exchange (PLEX) on alternate days with replacement with fresh frozen plasma (FFP). The arteriovenous fistula thrombosed from low anti-thrombin levels needing prophylactic heparin anticoagulation. Intravenous rituximab 750 mg (10 doses) was given on the non-PLEX days. The CD 19 + B cells decreased to 0.142% of total circulating lymphocytes. Both tacrolimus (0.1 mg/kg/day) and mycophenolate mofetil (30 mg/kg/day) were started a week before the date of transplantation, each in two divided doses.

The anti-A titers were measured after each session of PLEX. There was a quick reduction in the anti-A titers (Coombs) to 1:16, which remained stable until the 11th session of PLEX when, the titer dropped to 1:8, and he was taken up for transplantation. Figure 1 shows the desensitization protocol and decline in anti-A titers. He was given induction immunosuppression with two doses of anti-thymocyte globulin (Thymoglobulin®) – 1 and 3 mg/kg on consecutive days. Preoperatively, the donor ureter was found to be short and was anastomosed to the native ureter rather than a ureteroneocystostomy. A double J stent was temporarily left in situ. The recipient proximal native ureter was ligated.

- Desensitization protocol

Immediately after transplantation surgery, a final session of PLEX dropped titer to 1:2. In attempting ABOi transplant for the first time and with a high titer of anti-A antibodies, we monitored anti-A titers twice daily for the first 3 days after transplant, once daily for a week, alternate days for the next week, and weekly thereafter for a month. The anti-A titers remained at a nadir of 1:2 and on one occasion at 1:4 without graft dysfunction or requirement of intervention. Should there have been a rebound of anti-A titers, the patient and the team were prepared for further PLEX sessions and splenectomy if deemed necessary. His treatment was heavily subsidized considering the low socioeconomic background of the family.

The implantation graft biopsy was normal. Both the patient and his donor mother recovered well. Prednisolone was started at 20 mg per day and tapered to a maintenance dose of 7.5 mg per day. The doses of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were adjusted based on tacrolimus trough level and mycophenolic acid 6-h exposure monitoring. He received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and valganciclovir prophylaxis for 6 months.

He developed two episodes of urinary tract infections, the first in the fourth week after transplantation with Escherichia coli urosepsis. Following a second episode in the third month, he received antibiotic prophylaxis. There was a gradual graft dysfunction in the ninth month after transplantation with creatinine rising from 1.5 to 1.8 mg/dl. The anti-A titers continued to remain at 1:2. A renal biopsy did not reveal significant pathology. The doses of tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil were optimized based on therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) and the renal function improved. At 18 months, following another episode of urinary tract infection, he developed cytomegalovirus infection which resolved with valganciclovir treatment.

Although he required insulin for elevated blood sugars during the initial urinary tract infection, he had good glycemic control without medication until December 2019, when with a weight gain of 20 kg, he developed new-onset diabetes. During the first wave of the COVID pandemic in July 2020, he developed a mild SARS-Cov-2 infection. Currently, he is on prednisolone 7.5 mg, tacrolimus 0.75 mg twice daily, and mycophenolate mofetil 500 mg and 750 mg. His recent serum creatinine is 1.6 mg/dl, 24-h urine protein 120 mg, and anti-A titers are 1:2. Today, at 33 years of age, he is married, has a daughter of 9 months, and earns his living running a small restaurant. His mother remains healthy. His most recent TDM for immunosuppressive drugs showed tacrolimus trough of 5.8 ng/mL and mycophenolic acid 6-h AUC 44.2 mg.h/L.

The mechanism of accommodation accounts for the persistently low anti-A titers. This phenomenon likely results from a decrease in blood group antigenicity as a result of reduced expression on graft endothelial cells,[5] anti-apoptotic gene expression leading to resistance to humoral injury,[6] blood group chimerism,[7] and other postulated mechanisms. Worldwide, earlier reports showed an increased frequency of infections in ABOi transplant recipients compared to ABO compatible transplant recipients[8,9] but with the decrease in the intensity of desensitization, infection risks appear to be similar.[10] Retrospectively, we could have managed this transplantation with a less intense desensitization protocol. The present protocol involves a single dose of 375 mg/m2 rituximab on day 30, starting tacrolimus and mycophenolate from day 7, followed by PLEX with albumin replacement until antibody titers <1:8. Basiliximab is our preferred induction agent. This protocol is similar to those currently in practice and mitigates some of the ever-present latent infective risks and those in the community.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- ABO-incompatible renal transplantation in developing world-crossing the immunological (and mental) barrier. Indian J Nephrol. 2016;26:113-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- ABO-incompatible renal transplantation: The journey so far on a road less traveled. Indian J Transplant. 2018;12:177.

- [Google Scholar]

- ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation: Indian working group recommendations. Indian J Transplant. 2019;13:252.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences with renal homotransplantation in the human: Report of nine cases. J Clin Invest. 1955;34:327-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decrease of blood type antigenicity over the long-term after ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2011;25:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Accommodation of vascularized xenografts: Expression of “protective genes“by donor endothelial cells in a host Th2 cytokine environment. Nat Med. 1997;3:196-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endothelial chimerism after ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2012;93:709-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increase of infectious complications in ABO-incompatible kidney transplant recipients--A single centre experience. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:4124-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and outcomes of BK virus allograft nephropathy among ABO- and HLA-incompatible kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1320-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- ABO-incompatible living kidney transplants: Evolution of outcomes and immunosuppressive management: ABO-incompatible transplant immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:886-96.

- [Google Scholar]