Translate this page into:

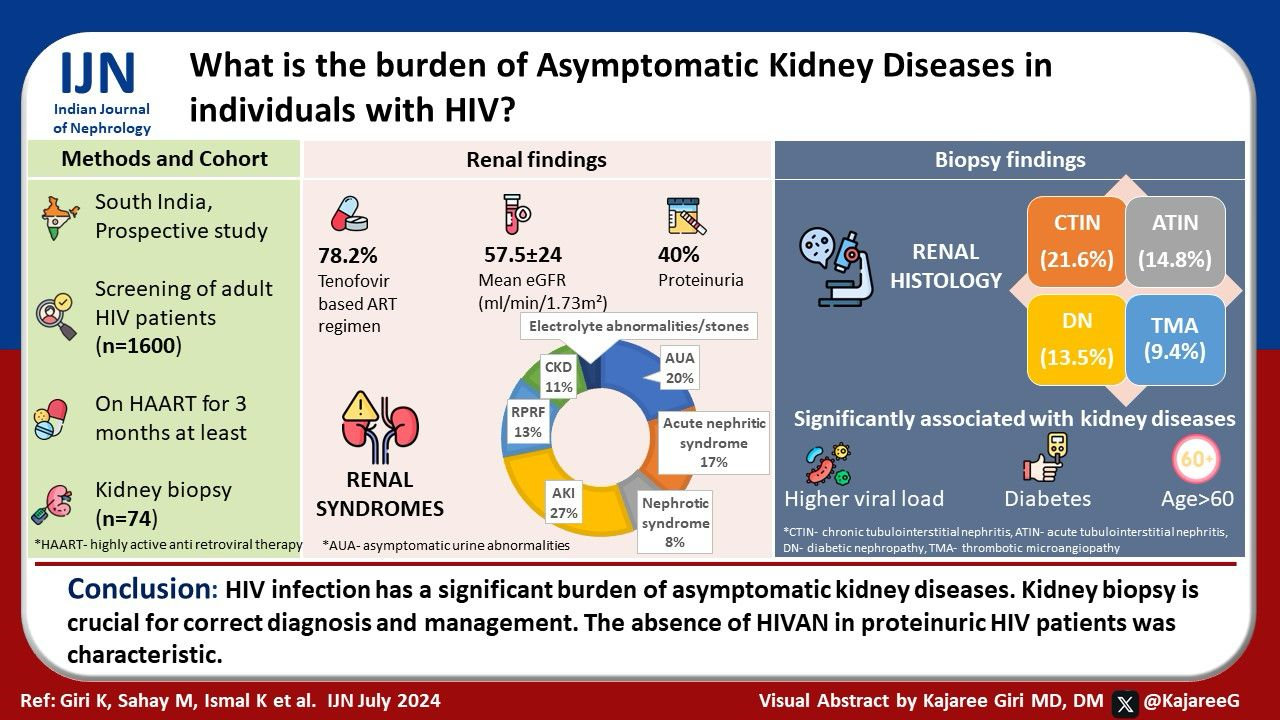

The High Burden of Asymptomatic Kidney Diseases in Individuals with HIV: A Prospective Study from a Tertiary Care Center in India

Corresponding author: Manisha Sahay, Department of Nephrology, Osmania Medical College and Hospital, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: drmanishasahay@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Giri K, Sahay M, Ismal K, Kavadi A, Rama E, Gowrishankar S. The High Burden of Asymptomatic Kidney Diseases in Individuals with HIV: A Prospective Study from a Tertiary Care Center in India. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:623-9. doi: 10.25259/ijn_10_24

Abstract

Background

HIV infection is associated with a significant kidney disease burden. This study is aimed to screen for kidney disease in all HIV patients on highly active anti retroviral therapy (HAART), study clinico-histological correlation, and assess the impact of early diagnosis on the clinical course.

Materials and Methods

It was a prospective, longitudinal study done in a tertiary care hospital. Adult HIV-infected patients, on HAART for at least 3 months, were screened for kidney disease. Kidney biopsy was done if indicated. Patients were treated as per standard guidelines. Results were analyzed at 3 months.

Results

Among 1600 patients, 966 were compliant with HAART and were tested. Two hundred and sixty-two patients completed the study duration. Out of these 262 patients 78.2% were receiving tenofovir-based ART regimen. Around 31.2% were hypertensive and 19.8% were diabetic. The mean eGFR was 57.5 ± 24 mL/min/1.73 m2. Around 19.8% had asymptomatic urine abnormalities, 40.1% had proteinuria, and 27.1% had AKI. Acute nephritic syndrome was seen in 16.4%, rapidly progressive renal failure (RPRF) in 13.3%, and CKD in 10.6% patients. Out of 74 patients who underwent biopsy, histology showed chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis in 16 (21.6%), acute tubulointerstitial nephritis in 11 (14.8%), diabetic nephropathy in 10 (13.5%), and thrombotic microangiopathy in 7 patients (9.4%). Higher viral load levels, diabetes mellitus, and age above 60 years were associated with kidney disease.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic HIV infection has a significant burden of kidney disease. Kidney biopsy is crucial for correct diagnosis and management. The absence of HIV associated nephropathy in proteinuric HIV patients is notable in this study.

Keywords

HIV

Histopathology

Kidney disease

Screening

Asymptomatic urine abnormalities

HIVAN-HIV associated nephropathy

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection has been a global pandemic. In 2021, an estimated 38.4 million people worldwide were living with HIV infection.1 In India, there are an estimated 23.48 lakh people living with HIV (PLHIV).1 HIV prevalence is higher in Telangana (0.49%) compared to national figures (0.24%).

Kidney disease (proteinuria and or low GFR) has been commonly reported among PLHIV. The first description of severe proteinuria with a rapid loss of kidney function in HIV-infected patients was published in 1984, where a characteristic lesion named HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) was reported, with histological features of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS).2 Kidney disease in HIV may be caused by a combination of any of the mechanisms. HIV infection of the kidney (intrarenal HIV gene expression), immunologic responses to the virus, opportunistic infections and neoplasms that characterize AIDS, and various therapies or hemodynamic derangements or lesions related to comorbidities.3-5

Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) causes effective and persistent viral load suppression, eventually decreasing immune activation. As the life expectancy of PLHIV has increased, several factors such as HAART, age-related comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease), HIV-related coinfections (Hepatitis C, Hepatitis B, tuberculosis), low CD4 counts, lipodystrophy, and polypharmacy have a significant impact on the development of kidney diseases. HIV-infected adults are 32% more likely to have hypertension than HIV-uninfected adults and it is an independent risk factor for renal diseases.6,7

The burden of kidney disease in PLHIV in India varies between 7% and 30%.8 There is paucity of data on the prevalence, spectrum as well as clinico-histopathological correlation of kidney disease in PLHIV from India. This study aimed to screen for kidney disease in PLHIV on HAART therapy. The objectives were to study the clinical-histological correlation of kidney disease in PLHIV on HAART, identify the risk factors predictive of kidney disease, and assess the impact of early diagnosis on the clinical course of these patients.

Materials and Methods

The study was hospital-based, investigator-initiated, prospective, longitudinal study, conducted from January 2022 to December 2022. It was conducted in a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India. It is the largest tertiary anti-retroviral treatment (ART) center in the state under National AIDS Control Organization (NACO). It provides ART services, diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring for both inpatients and outpatients and caters to around 1000 patients per month. Institutional ethics board approval has been taken.

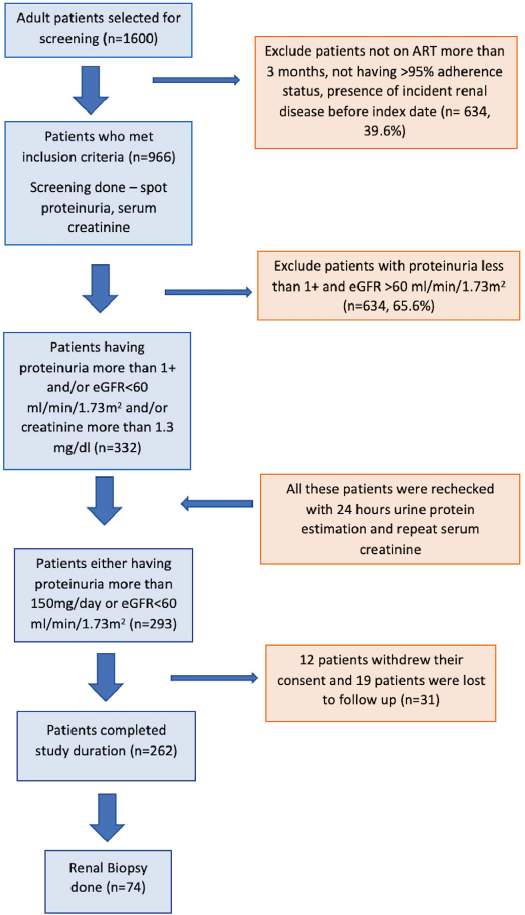

The inclusion criteria for screening were HIV-positive patients aged more than 18 years, on HAART for at least 3 months, compliant with treatment with more than 95% adherence. The patients excluded from screening were pregnant patients, those diagnosed with CKD due to other causes, individuals with active urinary tract infections, and those unwilling to give consent.

All consecutive HIV seropositive patients attending the outpatient HIV clinic, kidney clinic, or admitted under medicine or nephrology services were considered for screening. A written informed consent was obtained from all patients. They were screened with spot proteinuria and serum creatinine. The confounding factors of proteinuria (heavy exercise, cardiac failure, uncontrolled hyperglycemia, uncontrolled hypertension, acute illness, and urinary tract infection) were excluded. Patients with serum creatinine ≥1.3 mg/dl and/or eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and/or ≥1+ spot proteinuria were included. The included patients underwent a complete urine examination, 24-h urinary protein, electrolyte panel, and repeat creatinine estimation to negate any laboratory errors. Patients were categorized into syndromes (AKI, CKD, RPRF, nephrotic syndrome, acute nephritic syndrome, asymptomatic urine abnormalities, electrolyte abnormalities) as per standard definitions.

A structured questionnaire was used for data collection. Sociodemographic history, clinical history, comorbidities, co-infections, and the treatment history were gathered. Records of previous, baseline, and current biochemical investigations, chest roentgenogram, and ultrasonography of the kidney were noted. eGFR was calculated using CKD-EPI. Urine was analyzed for protein, albumin, albumin-to-creatinine ratio, nitrite, red blood cells, white blood cells, and pH using the urine chemistry analyzer (Cybow reader 300) and 12C Cybow strips. Kidney biopsy was performed if clinically indicated under ultrasound guidance with a biopsy gun (BARD 18 G, 22 mm, cutting edge) and samples were sent for light and immunofluorescence microscopy. All patients were advised for follow-up in our outpatient kidney clinic. Patients having minimum follow-up monthly for three consecutive months were included. The algorithm depicting recruitment and follow-up is given in Figure 1.

- Consort diagram. eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate. ART: Anti-retroviral treatment.

The data from questionnaires were entered into Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 24. Summary statistics were determined as means with standard deviation, median, and range for continuous data and frequencies with percentages for categorical data. Continuous data were analyzed using Student’s t-test. The association between independent and dependent variables was determined using univariate analysis; multivariate analysis was used to adjust for confounders. A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Among 1600 patients, 966 were compliant with HAART and were tested [Figure 1]. Two hundred and sixty two patients (27.2%) had kidney disease. The baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 262) are given in Table 1. The recommended first choice of therapy in this ART center was tenofovir (TDF 300 mg) + lamivudine (3TC 300 mg) + dolutegravir (DTG 50 mg) regimen (TLD) as a fixed-dose combination in a single pill once a day. All patients diagnosed with HIV infection were eligible for HAART therapy irrespective of their CD4 counts or viral load status.

| Characteristics | N = 262 (mean +/– SD) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 69 | 26.4 |

| Male | 193 | 73.6 |

| Education level | ||

| No formal education | 56 | 21.4 |

| Secondary education level | 114 | 43.5 |

| Higher education level | 92 | 35.1 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married/Cohabiting | 116 | 44.2 |

| Unmarried | 84 | 32 |

| Divorced | 62 | 23.8 |

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 46.51 ± 10.8 | |

| Occupation | ||

| Employed (Government/private) | 171 | 65.2 |

| Unemployed/part time work | 91 | 34.8 |

| Mode of acquisition | ||

| Presumed sexual | 172 | 65.6 |

| Nonsexual | 90 | 34.4 |

| HIV Positivity of partners | ||

| Positive | 72 | 27.4 |

| Negative | 105 | 40 |

| Not known | 85 | 32.6 |

| Address | ||

| Urban | 165 | 62.9 |

| Rural | 97 | 34.1 |

| CD4 count (mean ± SD) (cells/microliter) | 618 ± 303 | |

| Median | 460.43 | |

| Range | 6–2044 | |

| Viral load (mean ± SD) (copies/mL) | 7332 ± 28694 | |

| Virological suppression achieved | 176 | 67.2 |

| Not achieved | 86 | 32.8 |

| WHO clinical stage | ||

| Stage 1 | 132 | 50.4 |

| Stage 2 | 92 | 35.1 |

| Stage 3 | 34 | 12.9 |

| Stage 4 | 4 | 1.6 |

| Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis | ||

| Patients taking | 68 | 25.9 |

| Patients not taking | 194 | 74.1 |

| Average time duration since initiation of HAART and screening | 6 ± 2.5 years | |

| Coinfections | ||

| Tuberculosis (pulmonary + extrapulmonary) | 8 (5 + 3) | 3.05 |

| Hepatitis B | 11 | 4.19 |

| Hepatitis C | 13 | 4.96 |

| Others | 23 | 8.77 |

| ART regimen used | 205 | |

| Tenofovir based | 57 | 78.2 |

| Non-tenofovir based | 21.8 | |

| Hypertensive | 82 | 31.2 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mean ± SD) mmHg | 142 ± 21 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mean ± SD) mmHg | 86 ± 15 | |

| Diabetic | 52 | 19.8 |

| Random blood glucose (mean ± SD) | 154 ± 11.5 | |

| Median (mg/dl) | 138 | |

| Range (mg/dl) | 75–484 |

SD: standard deviation, CD4: clusters of differentiation 4, HAART: highly active anti retroviral therapy, ART: anti retroviral therapy.

The biochemical parameters of the study population (n = 262) are given in Table 2. Among the 966 patients who were screened, 27.2% of patients had kidney disease. The mean eGFR (CKD EPI) was 57.5 ± 24 mL/min/1.73 m2. The microangiopathic blood picture was found in two patients and in one patient histopathology revealed thrombotic microangiopathy. Low C3 was found in five patients (biopsy showed infection-related glomerulonephritis in three cases). Among clinical renal syndromes, the majority of the patients (27.1%) had AKI, followed by asymptomatic urine abnormalities (19.8%) and acute nephritic syndrome (16.4%). Among the distinct category of patients having asymptomatic urine abnormalities (n = 52), the majority 48.2% (25) had microscopic hematuria; 44.2% had proteinuria 150–1000 mg/dl and 7.6% had nephrotic range proteinuria.

| Characteristics | N = 262 (mean +/– SD) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 9.25 ± 2.534 | |

| Total Leukocyte count (cells/cmm) | 9237 ± 237 | |

| Blood urea (mg/dl) | 82 ± 23.947 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 3.36 ± 1.67 | |

| Less than 1.3 mg/dl | 82 | 31.3 |

| 1.3–3 mg/dl | 127 | 48.4 |

| More than 3 mg/dl | 53 | 20.3 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 2.92 ± 0.862 | |

| Serum calcium (mg/dl) | 8.30 ± 0.947 | |

| Serum phosphorus (mg/dl) | 3.256 ± 0.862 | |

| eGFR value (mean ± SD) (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 57.5 ± 24 | |

| Median | 72 | |

| Range | 6–144 | |

| More than 90 | 33 | 12.5 |

| 60–90 | 68 | 25.9 |

| 30–59 | 89 | 33.9 |

| 15–30 | 52 | 19.8 |

| Less than 15 | 20 | 7.9 |

| Complete urine examination findings | ||

| Microscopic hematuria | 38 | 14.5 |

| Proteinuria more than 150 mg/dl (1+) (excluding nephrotic range) | 105 | 40.7 |

| Microscopic hematuria + proteinuria | 82 | 31.29 |

| Nephrotic range proteinuria | 22 | 8.39 |

| Normal | 15 | 5.75 |

| UPCR | ||

| Less than 0.2 | 33 | 12.6 |

| 0.2–2 | 182 | 69.3 |

| More than 2 | 47 | 18.1 |

| 24 hours urine protein excretion (g/day) | 2.6 ± 2.53 | |

| Median (g/day) | 1.324 | |

| Range (g/day) | 0.4 - 13 | |

| Kidney syndromes | ||

| Asymptomatic urine abnormalities (AUA) | 52 | 19.8 |

| Proteinuria 150–1000 mg/dl (1+ to 3+) | 23 | 44.2 |

| Nephrotic range proteinuria | 4 | 7.6 |

| Microscopic hematuria | 25 | 48.2 |

| Acute nephritic syndrome | 43 | 16.4 |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 22 | 8.3 |

| AKI | 71 | 27.1 |

| RPRF | 35 | 13.3 |

| CKD | 28 | 10.6 |

| Others (electrolyte abnormalities/nephrolithiasis) | 11 | 4.2 |

| Electrolyte abnormalities | ||

| Hypophosphatemia | 6 | 2.2 |

| Hyperphosphatemia | 3 | 1.1 |

| Hypokalemia | 3 | 1.1 |

| Hyperkalemia | 5 | 1.9 |

| Hypocalcemia | 28 | 10.6 |

| Metabolic acidosis | 18 | 6.8 |

| Glycosuria in absence of hyperglycemia | 6 | 2.2 |

| Histopathology involvement (N = 74) | ||

| Glomerular | 32 | 43.2 |

| Tubular | 23 | 31.3 |

| Vascular | 7 | 9.4 |

| Glomerular + tubular | 7 | 9.4 |

| Glomerular + vascular | 5 | 6.7 |

SD: standard deviation, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, UPCR: urine protein creatinine ratio, AKI: acute kidney injury, RPRF: rapidly progressing renal failure, CKD: chronic kidney disease.

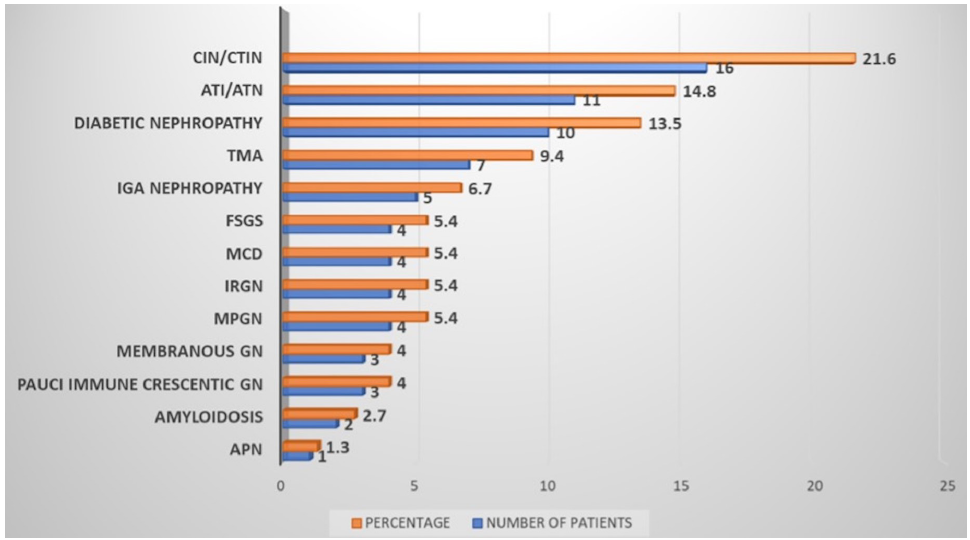

The kidneys were normal-sized in 63.3% (166), bulky in 13.3% (35), and contracted in size, with altered echotexture in 23.4% (61) patients. The histopathology of the study population (n=74) is shown in Figure 2. The majority 21.6% (16) patients had chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis (CTIN) followed by acute tubulointerstitial nephritis (ATIN) (14.8%, 11), diabetic nephropathy (13.5%, 10), and thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) (9.4%, 7). Four patients had membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) pattern on light microscopy. They were sent for electron microscopy; two of them revealed additional findings of segmental sclerosis with focal foot process effacement labeled as evolving secondary FSGS and other two showed only focal foot process effacement labeled as having podocytopathic changes. Two patients had collapsing FSGS but none of them had microcystic tubular dilatation and interstitial cell infiltrate and hence could not be classified as classical HIVAN.

- Histopathology—HIV renal disease; CIN/CTIN: chronic interstitial nephritis/chronic tubulo-interstitial nephritis, ATI: acute tubular injury, ATN: acute tubular necrosis, TMA: thrombotic microangiopathy, IGA: IgA nephropathy, FSGS: focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, MCD: minimal change disease, IRGN: infection related glomerulonephritis, MPGN: membranoproliferative glomerular disease, GN: glomerulonephritis, APN: acute pyelonephritis.

Crescents were noted in 13 (17.5%) patients (three had pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis, three had diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis, two had IgA nephropathy, and the rest had diabetic nephropathy). Mesangial hypercellularity was noted in 22 patients (29.7%). Immune deposits were noted in 46 cases (62.1%) 22 patients had predominant C3; 10 had C3, IgM, and IgG; 6 had C3 and IgM deposits; 5 had IgA deposits; and the rest had other combinations of deposits. Chronicity more than 50% was noted in 12 patients (16.2%).

The clinico-histopathological correlation reveals a significant burden of kidney disease in HIV patients with asymptomatic urine abnormalities [Table 3]. Among the patients having CTIN and ATIN on renal histology, 50% (eight) and 54.5% (six) patients presented clinically as cases of asymptomatic urine abnormalities (AUA). Histology revealed thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) in seven cases, of which 57.1% (four) patients presented as AUA.

| Histopathology | Asymptomatic urinary abnormalities | Acute nephritic syndrome | Nephrotic syndrome | RPRF | AKI | CKD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTIN (n = 16) | 8 (50%) (p < 0.05) | - | - | 3 (21.4%) | 2 | 3 (21.4%) |

| AIN/ATIN (n = 11) | 6 (54.5%) (p < 0.05) | - | - | 2 (18.2%) | 3 (27.2%) | - |

| Diabetic nephropathy (n = 10) | 3 (30%) | 1 | 1 | 2 (22.2%) | 1 | 2 |

| TMA (n = 7) | 4 (57.1%) (p < 0.05) | 1 | - | 2 | - | - |

| IGAN (N = 5) | 1 | 2 | - | 2 | ||

| FSGS (n = 4) | 1 (20%) | - | 2 (40%) | 1 (20%) | - | - |

| MCD (n = 4) | - | 1 | 3 (75%) | - | - | - |

| IRGN (n = 4) | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - |

| MPGN (n = 4) | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - |

| Membranous (n = 3) | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Crescentic GN (n = 3) | - | 1 | - | 2 | - | - |

| Amyloidosis (n = 2) | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | - |

| APN (n = 1) | - | - | - | - | 1 | - |

AIN/ATIN: Acute interstitial nephritis/acute tubulointerstitial nephritis, ATN: Acute tubular necrosis, APN: Acute pyelonephritis, CTIN: Chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis, IGAN: IgA nephropathy, IRGN: Infection-related glomerulonephritis, MPGN: Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, MCD: Minimal change disease, DN: Diabetic nephropathy, FSGS: Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, TMA: Thrombotic microangiopathy. Bold values indicate p value <0.05 as statistically significant.

The factors predictive of kidney disease among HIV patients on HAART (n = 966) reveal that patients with age more than 60 years, viral load more than 1000 copies/mL, and diabetes mellitus had a fivefold increased likelihood of getting kidney disease. Patients with CKD grade IV and V were started on conservative management with lifestyle modification, antihypertensives, angiotensin converting enzymes inhibitors (ACEI), statins, anemia correction, bicarbonate supplementation, and strict glycemic control. Mean follow-up duration was 12 weeks (range 4 to 20 weeks). All patients MPGN (four), FSGS (four), MCD (four), crescentic GN (three), and IGAN (two) were started on low-dose steroids (0.5 mg/kg/day) and ACEI along with HAART. All cases of MCD, two patients of MPGN and one patient of FSGS had more than 50% reduction in proteinuria after 1 month of treatment. The response of FSGS to steroids was largely variable. One patient with serum creatinine–2.2mg/dl, eGFR 20.5 mL/min, and 24-h proteinuria of 1.4 g/day did well on ACEI and low-dose steroid (0.5 mg/kg/day). He had eGFR of 45 mL/min and proteinuria of 350 mg/day after 6 weeks of treatment. In other cases of FSGS, there was no significant improvement in eGFR. Three patients of crescentic GN were dialysis dependent at the end of 8 weeks. All cases of IRGN (four) were managed with antihypertensives and ACEI; there was remission of proteinuria and recovery of kidney function of three patients after 8 weeks.

Discussion

This study shows a substantial burden of kidney disease among the HIV-infected patients screened. A retrospective analysis of the DC Cohort, showed incidence of kidney disease to be 0.77 episodes per 100 person-years in 2011–2015.4 Kidney disease was also evident in 25% of the cases in Dar-Es-Salam, Tanzania.9 Whereas, in a similar study in Mulago, Uganda, the prevalence was found to be 2.52%.10 Two different studies from North India, report the prevalence of kidney diseases in 17.3% and 46.4% of HIV-infected patients, respectively.8,11 Another study from Eastern India reports kidney disease in 22.9% of HIV-infected patients who are ART naïve compared to 13.7% of patients who are on ART.12 Prior studies reveal higher magnitudes (53–76%) of kidney disease among ART-naive patients, it confirms that HIVAN has decreased in the era of HAART.13 AKI may occur due to drugs or infections.

Microalbuminuria is an early predictor of progressive cardiovascular and kidney diseases and is also seen to be linked with accelerated progression of HIV. Proteinuria was reported in 29.8% and 14% of patients, respectively, in two studies from the USA.14,15 The reported prevalence of proteinuria was low (5-6%) in studies from Africa and Brazil.13,16 In this study, higher prevalence rates of proteinuria (40.07%) were noted even in those with insignificant viral load. This emphasizes the need for routine screening of HIV-infected patients including those with good viral suppression. Prompt control of microalbuminuria has shown to retard progression of kidney disease and reduce cardiovascular risks.

In prior studies, HIVAN had been consistently reported to be the most common glomerular lesion in HIV-positive patients in the US, Brazil, African countries, and Western Europe, whereas to a lesser degree in the Asian Indian cohort.11 However, the current prevalence of HIVAN is declining as a result of the widespread use of HAART. Swanepoel et al. reported biopsy diagnosed HIVAN in 55.3% in 2011.17 Lescure et al. also showed that HIVAN decreased with time between 1995 and 2007.18 Kudose et al. reported 14% of HIVAN in a biopsy series between 2011 and 2018 from a major US center.19 Similarly, Varma et al. from India did not find any case of HIVAN but reported one case of collapsing FSGS and four cases of noncollapsing FSGS.20 The first case of classical HIVAN was reported in India from the state of Jammu and Kashmir.21

In the present study, 74 (28%) patients were underwent kidney biopsy which is greater than most studies.9,11,13 Glomerular lesions constituted 43.2% in this study. Even tubular and vascular lesions were substantially more than other studies.8,11 Our cohort showed an increased proportion of histological diagnosis of FSGS (NOS) type, which has been hypothesized to represent a partially treated or attenuated form of HIVAN. Similarly, the increase in the trend for tubulointerstitial lesions in HIV patients in this study may be attributed to the use of tenofovir or cotrimoxazole or immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).22 A high incidence of interstitial nephritis (48%) was also reported in a multicentric study from Paris.23

HIV-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) has been reported in 9.4% of our biopsy cohort, which is not evident in any other studies. To our surprise, patients with histological evidence of TMA (57%), CTIN (50%), ATIN (54.5%), diabetic nephropathy (30%), and FSGS (20%) had no clinical symptoms (asymptomatic urine abnormalities). They were identified on routine screening. Hence, following the advent of the HAART era, routine screening is necessary to identify kidney diseases promptly.

As patients with HIV live longer, they are at more risk of chronic diseases like diabetes and hypertension, which likely increase the prevalence of CKD. Measurement of proteinuria and early nephrology referral has been shown to improve outcomes in patients with CKD. Hence, the importance of routine screening in HIV patients is once again emphasized.

Overt kidney failure due to TDF is rare (0.3%).24 Characteristic tenofovir-induced intracytoplasmic inclusions in proximal tubular cells are rare and were not seen in any of our patients, though the majority were on a tenofovir-based regimen.

This study has done a screening of 1600 patients and included the maximum number of histology reports, to provide a bird’s eye view of the kidney diseases in HIV patients on HAART. This study suggests that incorporating screening for kidney disease and diabetes in all HIV patients in the ART clinic is of urgent need. This will not only enable early detection, treatment, and monitoring of HIV patients for such complications and improve the quality of life but also by reducing the need for kidney replacement therapy, it will decrease the financial and economic burden of the country.

The limitations of the study were electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry could not be carried out on all samples, which might have detected more cases of immune complex diseases. APOL1 genotyping was not determined. There was a short median follow-up duration of our subgroup of patients.

Asymptomatic HIV-infected patients have a significant burden of kidney diseases. HIV is a high-risk group; hence, routine screening with proteinuria and GFR is mandatory. Renal biopsy is crucial for correct diagnosis and management of HIV-related kidney disease. Age, diabetes, and viral load of more than 1000 copies/mL are independent predictors of kidney diseases in HIV. The best strategy to combat this is frequent screening, early initiation of HAART, and strict control of hypertension and diabetes.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- India HIV estimates 2021 Fact sheet. Available from http://naco.gov.in/hiv-facts-figures [Last accessed 2024 January 02].

- Renal disease in patients with AIDS: A clinicopathologic study. Clin Nephrol. 1984;21:197-204.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and etiology of acute renal failure among ambulatory HIV-infected patients. Kidney Int. 2005;67:1526-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DC cohort executive committee. Incidence and risk factors for renal disease in an outpatient cohort of HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4:1075-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional study of HIV-seropositive patients with varying degrees of proteinuria in South Africa. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2243-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higher prevalence of hypertension in HIV-1-infected patients on combination anti-retroviral therapy is associated with changes in body composition and prior stavudine exposure. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:205-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conference Participants. Kidney disease in the setting of HIV infection: Conclusions from a kidney disease: Improving global outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2018;93:545-59.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- HIV associated renal disease: A pilot study from north India. Indian J Med Res. 2013;137:950-6.

- [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Renal dysfunction among HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy in dar es salaam, tanzania: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nephrol. 2020;2020:8378947.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of renal dysfunction among HIV infected patients receiving Tenofovir at Mulago: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:232.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Kidney disease in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients: Absence of human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy was a characteristic feature. Indian J Nephrol. 2017;27:271-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional study on renal involvement among HIV-infected patients attending a tertiary care hospital in Kolkata. Transactions of Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2018;112:294-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in newly diagnosed patients with human immunodeficiency virus in Ilorin, Nigeria. J Bras Nefrol. 2015;37:177-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abnormal urinary protein excretion in HIV-infected patients. Clin Nephrol. 1993;39:17-21.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of persistent asymptomatic proteinuria in HIV-infected outpatients and lack of correlation with viral load. Clin Nephrol. 2001;55:1-6.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A cross-sectional study of HIV-seropositive patients with varying degrees of proteinuria in South Africa. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2243-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV and renal disease in Africa: The journey so far and future directions. Port J Nephrol Hypert. 2011;25:11-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- HIV-associated kidney glomerular diseases: Changes with time and HAART. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:2349-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The spectrum of kidney biopsy series in HIV-infected patients in the modern era. Kidney Int. 2020;97:1006-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spectrum of renal lesions in HIV patients. J Assoc Physicians India. 2000;48:1151-4.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy in an HIV-positive patient in a low-incidence belt. Indian J Nephrol. 2010;20:211-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathological correlation of kidney disease in HIV infection pre- and post-ART rollout. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0269260.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Renal disease associated with HIV infection: A multicentric study of 60 patients from Paris hospitals. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8:11-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for the treatment of HIV infection in adults: The first 4 years. AIDS. 2007;21:1273-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]