Translate this page into:

The Ongoing Saga of Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Gastroenteritis in Developing World

Corresponding author: Manisha Sahay, Department of Nephrology, Osmania General Hospital, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: drmanishasahay@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Sahay M. The Ongoing Saga of Acute Kidney Injury Associated with Gastroenteritis in Developing World. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:279-81. doi: 10.25259/IJN_19_2024

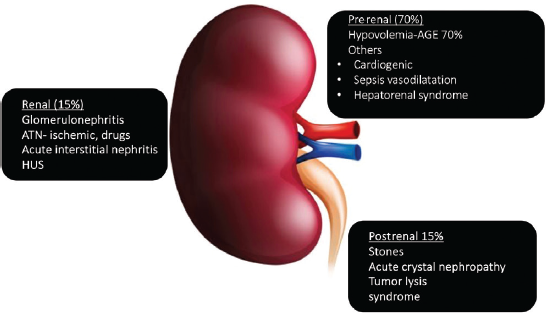

The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) is reported as 22% in the high-income countries (HIC) and 7.5% in lower- and lower-middle-income countries (L/LMIC).1 AKI in HIC is different from AKI in L/LMIC [Table 1]. Prerenal AKI is the most common cause of AKI in L/LMIC and the predominant cause of prerenal AKI is acute gastroenteritis (GE) [Figure 1].

| HIC | L/LMIC | |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Hospital setting | Community acquired |

| Age | Older | Younger |

| Comorbidities | Diabetic, multiple comorbidities, CKD, cardiovascular disease | Usually none, occurs in healthy individual |

| Etiology | Nephrotoxins, contrast, cardiogenic | Gastroenteritis, infections, toxins, insect bites |

| Prognosis | Poor | Better |

| Prevention | Difficult as multiple comorbidities | Preventable |

HIC: high-income countries, L/LMIC: lower-middle-income countries, AKI: acute kidney injury, CKD: chronic kidney disease

- Etiology of AKI. AGE: acute gastroenteritis, ATN: acute tubular necrosis, HUS: hemolytic uremic syndrome, AKI: acute kidney injury

In a study in this issue of IJN, among 923 adults admitted with GE, 10.07% of the patients had AKI.2 In a study from Saudi Arabia, which included both adults and children, in 300 patients with GE, 41 (13.6%) had AKI.3 Bradshaw et al. showed that one in ten adults hospitalized with acute gastroenteritis (AGE) experienced AKI.4 GE is a common ailment and 10% incidence of AKI in GE in the current study implies a substantial disease burden.

In the current study, among 313 AKI patients treated in the hospital, 29% was attributed to AGE.2 In an earlier study done two decades ago, among 187 cases of AKI in a government hospital, 23.5% was attributed to GE.5 Thus, despite marked improvement in sanitation and several schemes for control of diarrhea, it is unfortunate that GE-AKI remains the predominant cause of AKI. Vairakkani et al. reported a lower incidence of GE-AKI which accounted for only 5% of the total AKI burden.6 This may reflect a seasonal variation with a higher incidence during monsoons. GE-AKI is significantly more common in the elderly.4,5 However, in the current study, patients above 70 years were excluded.

Those with comorbidities may be more prone to GE-AKI. In a study by Bogari et al., the most common comorbidity was malignancy, especially leukemia and lymphoma.3 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and hypertension were associated with increased odds of AKI.4 In the current study, 28% had type 2 diabetes, 30% were hypertensive, and 24% had a history of alcohol consumption. However, patients who had a prior history of CKD, prior renal transplant, or patients having contracted kidneys were excluded; hence the incidence of AKI in the current study might have been lower than studies that included these risk groups.2

In the current study,2 8.6% of GE was attributed to Vibrio cholerae, while cultures were negative in others due to prior antibiotic use. Viral studies were not done in the current study. In a study by Tatte et al., in 110 adults with AGE from Western India, the prevalence of enteric viruses was rotavirus A (RVA): 38.5%; enterovirus, 23.1%; astrovirus, 23.1%; adenovirus, 7.7%; human bocavirus, 7.7%; and norovirus, 0%.7 The nonviral causes include bacteria (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Campylobacterjejuni, Shigella spp, Salmonella spp, Yersinia, and Escherichia coli) and parasites (e.g., Giardia and Cryptosporidium). In a study from Saudi Arabia, the most frequent cause of AGE was Salmonella spp. (n = 163, 53.3%) and AKI was seen in 36.5% with Salmonella infection while Clostridium difficile diarrhea was associated with AKI in 51.2%.3 Norovirus, often reported as a frequent cause of AGE was not documented in these studies.

The major pathogenetic mechanism of AKI in AGE is prerenal or ATN. However, severe ATN may activate toll-like and other pattern recognition receptors on resident immune cells with microinflammation with infiltration of neutrophils, M1 macrophages, generation of cytokines, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction. Unless there is prolonged hypoperfusion, numerous counter-regulators promote resolution of necroinflammation and healing. Regeneration occurs by the proliferation of progenitor cells (immature tubular cells) which exist along the nephron. If these cells are lost, as occurs in severe ATN/cortical necrosis, there is permanent loss of renal tissue.

Renal biopsy is indicated only in cases where recovery is delayed for more than two weeks or urine shows RBC and/or protein. Histology commonly shows acute tubular injury. In this study, ATN, and less commonly acute tubulointerstitial nephritis, were the commonest findings. Other lesions like hemolytic uremic syndrome, acute cortical necrosis, and proliferative glomerulonephritis may be seen rarely.2

AKI is mostly prerenal and can be prevented if identified early. Bogari et al. showed that 96.4% patients with AKI had mild dehydration.3 Thus, kidney injury can be induced even by mild dehydration. Mahajan et al. noted that volume depletion was the most common precipitating factor for AKI.8 Rapid and effective restoration of extracellular fluid (ECF) volume within 4 h can prevent AKI.9 A significant proportion of patients with GE in the current study presented with shock, which highlights the lack of awareness of the public about early fluid resuscitation and also the inadequate implementation of standard protocols for volume resuscitation at the primary care level.

In the current study,2 71% were classified as having KDIGO stage 3 AKI, vasopressor support was required in 22.6% due to refractory hypotension, and 29% required dialysis, while in another study,5 64.1% needed dialysis. The dialysis rates may be higher in a tertiary hospital or those with a policy of early initiation of dialysis. Low rates of dialysis requirement in the current study may be due to early referral to the nephrology unit. Both peritoneal dialysis (PD) and hemodialysis (HD) are effective. In Muthusethupati’s study, 71.6% were managed by PD alone.6 PD is also more frequently used in LMIC: in children, those with shock, and when patients cannot be shifted to dialysis units. CRRT can also be offered; however, cost is prohibitive.

In the current study, 84.9% had complete recovery while 8.6% of patients progressed to CKD.4 In another study, CKD occurred in 24.6% of a general hospitalized population with varying causes of AKI after three years of follow-up.10 Thus, it is imperative to manage GE-AKI effectively to prevent progression to CKD. Though most cases in the current study recovered, this does not necessarily represent regeneration of the affected tubular cells, as some tubular cells die and do not regenerate but GFR still returns to normal by compensatory hypertrophy of unaffected tubular epithelial cells. This is a risk factor for CKD.

In the 1990s, the mortality was high—28% in one study5 and 53.7% in another.11 The current study reported 6.5% mortality which may reflect better awareness about AKI and availability of dialysis. Though predictors of mortality could not be assessed in this study, metabolic acidosis, hypotension, encephalopathy sepsis, advanced AKI stage, mechanical ventilation, leukocytosis, and hyperkalemia were associated with in-hospital mortality in most studies. Though the mortality was lower in this study as compared to the previous studies, it still does not meet the KDIGO goal of “0” preventable deaths from AKI.

This important study highlights that while we focus on novel and emerging causes of AKI, we often tend to neglect GE-AKI, which accounts for almost 30% of all cases of AKI. Majority of patients present late with shock—fluid resuscitation is often late and inadequate. Unlike other causes of AKI, GE-AKI is largely preventable with the provision of safe drinking water, provision of toilet facilities, education about handwashing and oral rehydration therapy at the public health level, and implementation of SOPs for volume resuscitation at the level of primary care centers and in ICUs. Prevention of GE-AKI will be a huge step toward realizing the International Society of Nephrology (ISN) goal of “0 by 25” and will also help reduce the CKD burden.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:607-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post-diarrheal acute kidney injury during an epidemic in monsoon – a retrospective study from a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:310-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute gastroenteritis-related acute kidney injury in a tertiary care center. Ann Saudi Med. 2023;43:82-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Acute kidney injury due to diarrheal illness requiring hospitalization: Data from the national inpatient sample. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1520-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure in South India. J Assoc Physicians India. 1987;35:504-7.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acute kidney injury in a tertiary care center of South India. Indian J Nephrol. 2022;32:206-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Circulation of unusual and diverse enteric virus strains in adults with acute gastroenteritis: A study from Pune (Maharashtra), Western India. Arch Virol. 2023;168:160.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting the outcome of acute renal failure among the elderly population in India: A hospital based study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2006;38:391-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical studies in Asiatic cholera II development of 2:1 Saline – Lactate regimen comparison of this regimen with traditional methods of treatment between April and May 1963. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1966;118:174-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Three-year outcomes after acute kidney injury: Results of a prospective parallel group cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015316.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure due to acute diarrhoeal diseases. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990;38:164-6.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]