Translate this page into:

Unusual Late Onset Recurrent Venous Thrombosis in Two Young Post Renal Transplant Recipients – Challenges in Diagnosis and Management with Review of Literature

Corresponding author: Ratan Jha, Department of Nephrology, Care Hospital, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad, India. E-mail: jharatan08@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Jha A, Rakesh A, Jha R, Avinash K. Unusual Late Onset Recurrent Venous Thrombosis in Two Young Post Renal Transplant Recipients – Challenges in Diagnosis and Manageement with Review of Literature. Indian J Nephrol. doi: 10.25259/IJN_207_2024

Abstract

The risk of thromboembolic complications, including recurrence, remains elevated in renal transplant recipients. We discuss two young patients seven and eight years post renal transplant with recurrent venous thrombosis necessitating indefinite anticoagulation. One patient received tenecteplase for pulmonary thromboembolism twice without any complication.

Keywords

Recurrent venous thrombosis

Tenecteplase therapy

Apixaban

Introduction

Recurrent venous thrombosis (VT) poses significant challenges in post-renal transplant recipients in the context of diagnosis, risk assessment, therapeutic choices, and strategies for preventing recurrence.1,2 We report two such cases in young kidney transplant recipients (KTR), highlighting the complexity of diagnosis and management.

Case Reports

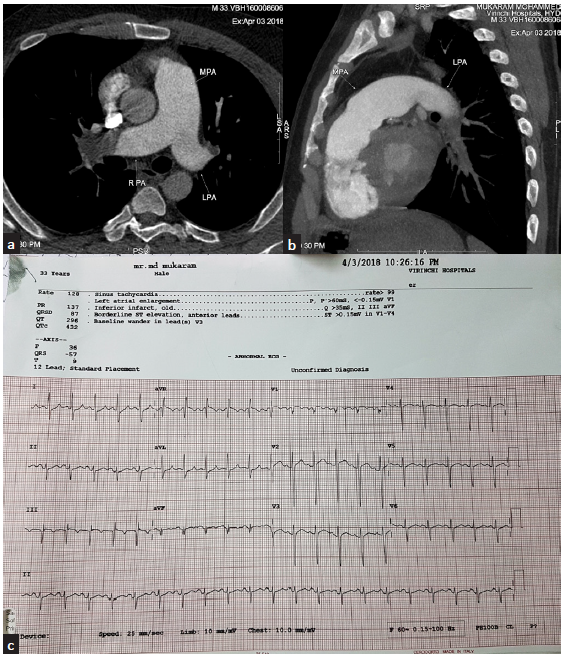

Case 1: A 33-year-old male KTR presented with sudden-onset dyspnea 7 years after renal transplant. He was anxious with tachypnea, tachycardia and hypoxia. Based on the confirmed diagnosis [Figure 1] of VT with pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), thrombolytic therapy with bolus tenecteplase (40 mg) was given followed by heparin and later monitored oral anticoagulant acenocoumarol. Oral anticoagulation was discontinued after 1 year and he was kept on antiplatelet aspirin. Two years later, the patient had non-severe COVID pneumonia. A year later, he experienced a recurrence of sudden onset severe breathlessness. His repeat evaluation for dyspnea reconfirmed it as deep vein thrombosis (DVT) with PTE recurrence [Table 1]. The patient received similar therapy initially as his first PTE 5 years back (Tenecteplase 40 mg followed with heparin). He was continued on low-dose apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily (as he had epistaxis with initial 5 mg dose) with no recurrence till 1 year of follow-up.

- (a) CT pulmonary angiogram – axial section at the level of pulmonary artery bifurcation reveals dilated pulmonary artery with large hypodense occlusive thrombus at right distal pulmonary artery and at the origin of left upper lobe artery. (b) Sagittal section reveals complete obstruction of left distal pulmonary artery with thrombus extending into lower lobar and segmental artery. (c) ECG – typical S1, Q3, T3 suggestive of PTE. CT = computerised tomography, ECG = electrocardiogram, S1 Q3 T3 = deep S wave in lead 1 Q wave in lead 3, inverted T in led 3, MPA = main pulmonary artery, RPA = right pulmonary artery, LPA = left pulmonary artery.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | During first attack | During second attack | First attack | Second attack |

| Age at presentation | 33 yrs (7 yrs post rtx) | 38 yrs (12 yrs post rtx) | 40 yrs (8 yrs post rtx) | 41 yrs (9 yrs post renal tx) |

| Donor | Mother 50 yrs | - | Live donor 40 yrs, HLA mismatched | - |

| Native kidney disease | Presumed chronic glomerulonephritis | - | Horseshoe kidney | - |

| Triple Immunosuppression | Tacrolimus/mmf/prednisolone (no induction agent used) | Triple immune suppression continued | Deflazacort/MMF/tacrolimus. (Basiliximab as induction agent) had post transplant diabetes mellitus 2 yrs post surgery and was on insulin and oral hypoglycemics | Triple immune suppression continued |

| Other comorbidities | 3 anti-hypertensive medication/no diabetes/high BMI 28.7 (weight 82 kg, height 169 cm) | Same comorbidity | Post transplant diabetes mellitus 2 yrs post surgery and was on insulin and oral hypoglycemic and 4 anti-hypertensive and high BMI 25 (weight 70 kg, height 165 cm) | Same |

| Presenting complaints | Sudden-onset dyspnea | Dyspnea at rest | Intense hemicranial headache on the left with vomiting | Left lower limb pain and swelling |

| Clinical examination | Patient was anxious, had mild bilateral pedal edema, blood pressure 120/70, respiratory rate 30/m, and pulse rate 124 and O2 saturation on room air 86%. | Respiratory rate 28/m, pulse rate 100/m, blood pressure 138/90 | Treated elsewhere. | Blood pressure 130/90, pulse rate 88/m, respiratory rate 14/m. Left leg swollen and tense compared to right and no inflammation. |

| CBP | TLC 12,500, Hb 14.1, platelet 2.4 lakh | TLC 9700, Hb 13.6, platelet 1.7 lakh | TLC 11500, Hb 15.1, platelet 2.48 lakhs |

TLC 11600, Hb 14.9, platelet count - 2.4 lakhs |

| Creatinine | 2.5 mg/dL | 3.3 mg/dL | - | 1.4 mg/dL |

| D-dimer | 800 ng/mL | 600 ng/mL | - | 4600 |

| NT-ProBNP | 1010 pg/mL | 881 pg/mL | - | - |

| Trop I | 129 | - | - | - |

| UPCR | 2.8 | 1.85 | 1.5 | 1.45 |

| Uric acid | 6.3 | 9.7 | 8.6 | 8.4 |

| HbA1c | - | - | - | 6.5 |

| Plasma Tacrolimus level | 5.2 ng/mL | 4.4 ng/mL | - | 14.5 ng/mL |

| Homocysteine level | 45 micromol/L | - | 65 micromol/L | |

| Thrombotic risk factors factor v leiden mutation/anti thrombin iii/protein C&S level/fibrinogen level/APLA antibody | Negative | - | Negative | - |

| ECG | Acute changes(s1/q3/t3pattern) | Non-specific ST, T abnormality | - | - |

| 2D-Echo of heart |

Dilated right atrium, right ventricle. No RWMA Dilated main pulmonary artery RVSP 80 mmHg TAPSE 0.7 mm/s |

Right ventricular dysfunction (right ventricular systolic pressure 75 mmHg | Normal | Normal |

| Doppler USG of lower limbs | Acute DVT (involving the right popliteal posterior tibial veins extending into gastrocnemius and soleal veins | DVT involving popliteal vein on the right side | - | Proximal DVT of the left lower limb involving femoral vein and extending to external iliac. |

| Imaging |

CTPA – Pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) V/Q scan – high probability scan |

CTPA-PTE, V/Q scan-nuclear ventilation perfusion scan showed high probability segmental and subsegmental perfusion defect in both lung fields | MRV-cerebral venogram, cerebral venous thrombosis of left transverse sinus | HRCT chest - normal |

| COVID-RT-PCR | - | Negative | - | Negative |

| Initial therapy | Thrombolysis with Inj. Tenecteplase 40 mg, heparin infusion followed by oral acenocoumarol 2 mg daily with dose adjusted 1/1.5 mg daily based on the patient in follow up | Thrombolysis with Inj. Tenecteplase 40 mg, heparin infusion followed by oral apixaban 5 mg twice daily reduced to 2.5 mg twice after 1 m | Heparin initially and followed with warfarin for 8 months | Enoxaparin for 5 days, hydration, reduction of Tacrolimus dose and started on apixaban 5 mg twice daily. |

| Follow up | Improvement in right ventricular dysfunction with resolution of DVT and PTE on imaging. Oralanticoagulation was discontinued after 1year and was kept on antiplatelet aspirin | Improvement in right ventricular dysfunction (drop of systolic bp from 75 to 45 mm of Hg). Initiated on low-dose apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily with no recurrence till 1 yr of follow up now (latest serum creatinine 3.1 mg%) | Stopped warfarin on his own after 8 months | DVT resolved completely without any further thrombotic episodes and is on apixaban since 4 years (last serum creatinine 2 mg %) |

APLA: antiphospholipid antibody, BMI: body mass index, CTPA: computerized pulmonary angiography, DVT: deep vein thrombosis, HR CT: high resolution CT, MRV: magnetic resonance venogram, PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism, RT PCR: reverse transcription based polymerase chain reaction, TAPSE: tricuspid annulus peak systolic excursion, UPCR: urine protein creatinine ratio, USG: ultrasonogram, V/Q scan: ventilation perfusion scan on nuclear imaging.

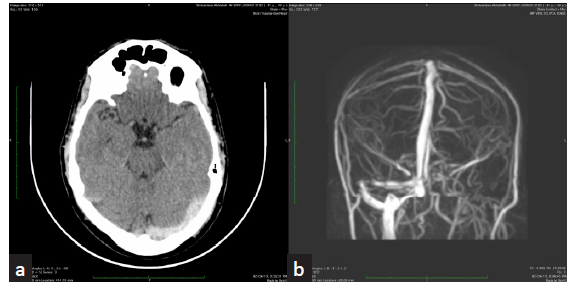

Case 2: A 41-year-old male KTR presented with left lower limb pain and swelling during COVID lockdown 9 years post transplant. His vitals were normal. His evaluation confirmed proximal DVT with a high potential for embolism [Table 1]. He suffered with intense hemi cranial headache last year with vomiting due to cerebral venous thrombosis [Figure 2] and was treated elsewhere with heparin followed by warfarin, which he discontinued after 8 months during the COVID lockdown. He was treated for his new DVT with enoxaparin followed with apixaban 5 mg twice daily as antithrombotic. He is doing well on apixaban at 3 year follow up so far with no thrombotic episodes even during his COVID pneumonia that he suffered one year later.

- (a) Non-contrast axial CT of brain reveals hyperdensity of left transverse sinus suspicious of thrombosis. (b) Phase-contrast 3D MRI coronal MIP shows absence of flow signal in left transverse sinus. Suggestive of thrombosis. CT - computer tomography, MRI- magnetic resonance imaging, MIP - maximum intensity projection.

Discussion

Kidney transplant recipients are at an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Timely diagnosis and adequate treatment with multidisciplinary support is essential. Estimates of thrombotic embolic (TE) risk have range between 0.6% and 25%. One of the detailed study conducted over 11 years observed a long-term risk of TE as 7.4%, a cumulative incidence at 5 years of 5.8% and an eightfold increased risk compared with the general population.2

The hypercoagulable state in KTRs is multifactorial; some of the risk factors are common with the general population while others are specifically related to transplant. Unique factors incriminated are post-transplant erythrocytosis, hyper homocysteinemia, chronic inflammation, proteinuria, GFR below 30 mL/mim, tacrolimus, sirolimus, hospitalization, low hemoglobin and lack of use of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors.2 A recent Indian study indicates that VTE events are more common in KTRs with advanced renal impairment.3 Our patients developed thrombotic events in late transplant period with mild renal dysfunction and had no impact on survival nearly 5 years follow up post initial event though renal function did decline as part of chronic allograft non-immune injury to some extent.

Hemodynamic stability dictates the algorithm of evaluation like ECG, chest X-ray, D-dimer, NT pro-BNP, troponin T, echocardiography of heart, lower limb venous Doppler, computerized pulmonary angiogram (CTPA), and ventilation- perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan). Patients are categorized into low, intermediate (low intermediate or high intermediate) or high risk based on clinical, radiological and biomarkers. According to the recent guidelines, the use of thrombolytic therapy is for high risk only but can be considered in selected cases of intermediate-risk PE as was our first case.4,5 Both low-dose thrombolysis and catheter-directed thrombolysis are effective with low bleeding risk in high-risk situations. Tenecteplase could be a good alternative to alteplase because of its easy availability and low cost. We employed in our case tenecteplase on both occasions with successful outcomes.

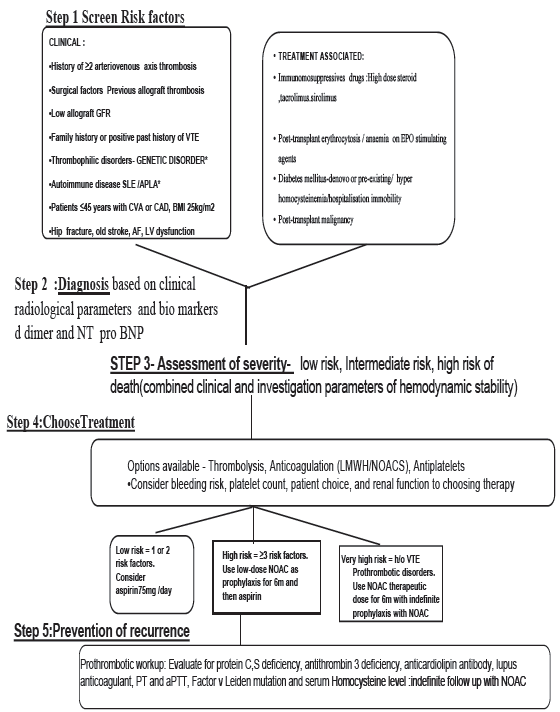

No overt detectable prethrombotic risk was noted in both the cases [Table 1]. KDIGO recommendation does not support routine screening of all transplant candidates for thrombophilia testing.6 Despite no consensus about the approach on risk assessment, treatment and follow up, we propose a clinical algorithm [Figure 3] that can be used in this situation based on KDIGO suggestion.

- Proposed algorithm for VTE risk assessment and thromboprophylaxis in renal transplant. VTE: Venous thromboembolism, BMI: Body mass index, LMWH: Low molecular weight heparin, NOAC: novel oral anticoagulants, EPO: Erythropoietin, AF: atrial fibrillation, LV: left ventricle, PT: prothrombin time, aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time, CTPA: CT pulmonary angiogram, NT pro BNP: nterminal pro brain natriuretic peptide.

Six months of anticoagulant use in idiopathic or unprovoked first events, as recommended, may not be adequate in renal transplant, and the need for further treatment should be re-evaluated. Our patients had recurrence after stopping the prophylaxis in the follow up necessitating anticoagulation indefinitely.

The role of novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) in renal transplant recipients, warrants careful attention, as recent studies have demonstrated its efficacy and safety in such transplant recipients with no drug interactions with calcineurin inhibitors.7

Conclusion

In the absence of identified thrombophilic risk factors, individualized algorithm use is needed for diagnosis and management of putative risk factors. It is of paramount importance to address the risk-benefit of appropriate thrombolytic therapy, choice of long-term oral anticoagulant and duration of prophylaxis based on clinical profile to ensure optimal outcome.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vascular and lymphatic complications. In: Knechtle SJ, Marson LP, Morris PJ, eds. Kidney transplantation principles and practice (8th ed). Elsevier Publishers; 2020. p. :458-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- The risk of thromboembolic events in kidney transplant patients. Kidney Int. 2014;85:1454-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, risk, and outcomes of venous thromboembolic events in kidney transplant recipients: A nested case-control study. Renal Failure. 2023;1:2161395.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Management of acute pulmonary embolism: Consensus statement for Indian patients. J Assoc Physicians India. 2015;63:41-50.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the european society of cardiology (ESC). 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3033-69.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KDIGO clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and management of candidates for kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2020;104:S11-03.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Can direct oral anticoagulants be used in kidney transplant recipients? Clin Transplant. 2021;35:e14474.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]