Translate this page into:

Wunderlich Syndrome: A Rare Case Associated with Bleeding Renal Angiomyolipoma (AML)

Corresponding author: Dr. Nidha Gaffoor, Assistant Professor, Department of Pathology, Dr. Chandramma Dayananda Sagar Institute of Medical Education and Research, Dayananda Sagar University, Ramanagara, Karnataka, India. E-mail: nidha.gaffoor@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Gaffoor N, Mysorekar VV, Gunadal S, Divyashree BN, Sandeepa S, Murali N. Wunderlich Syndrome: A Rare Case Associated with Bleeding Renal Angiomyolipoma (AML). Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:271–3. doi: 10.4103/ijn.ijn_397_23

Abstract

Renal angiomyolipoma (AML) is a benign mesenchymal tumor composed of fat, smooth muscle, and blood vessels. It represents 1–3% of solid renal tumors. Despite the benign nature of this tumor, it can be aggressive with locoregional extension. We describe a case of a 60-year-old female who presented with left flank pain and unstable blood pressure. A CT scan showed a renal mass with hemorrhagic densities. Peroperatively, bleeding from the renal mass was revealed, and the patient underwent radical nephrectomy. A myriad of symptoms such as acute flank pain, flank mass, and bleeding led to the diagnosis of Wunderlich syndrome, which is usually seen secondary to AML and renal cell carcinoma. Histopathologic examination helped in arriving at the diagnosis of renal AML with secondary changes, ruling out malignancy. Early diagnosis and immediate intervention saved her life and reduced morbidity. This case report helps in sensitizing clinicians and thus facilitates the detection of similar cases at the earliest.

Keywords

Angiomyolipoma

renal

syndrome

Introduction

Renal angiomyolipoma (AML) is a benign mesenchymal neoplasm consisting of thick dysmorphic blood vessels, smooth muscle, and adipose tissue, accounting for 1–3% of solid renal tumors.1 They represent the most common benign renal tumor, constituting 0.3–3% of all renal masses, and are typically diagnosed in middle-aged adults. While most AMLs are sporadic, some are associated with tuberous sclerosis complex.2 Often incidentally discovered on imaging, they can manifest with symptoms such as flank pain, gross hematuria, or severe retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Despite their benign nature, AMLs can exhibit locoregional and venous extension, occasionally leading to life-threatening bleeding necessitating urgent intervention.3

Case Report

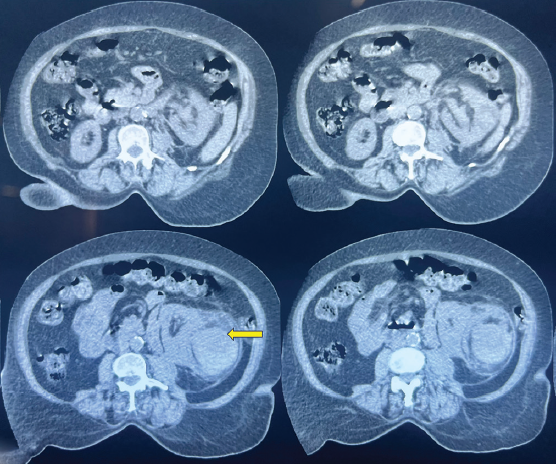

A 60-year-old postmenopausal woman presented with a one-week history of dull aching left flank pain and constipation. Physical examination revealed severe pallor and tachycardia (heart rate: 100 beats per minute) with a tender, bimanually palpable mass in the left lumbar region. Laboratory investigations indicated a hemoglobin level of 6.1 g/dL and elevated serum creatinine (2.1 mg/dL). Non-contrast computerized tomography (NCCT) of the abdomen revealed a large heterogeneous exophytic mass in the left kidney measuring 10.2 × 9.2 × 7.9 cms, containing fat and hemorrhagic densities, with anterior displacement of the descending colon [Figure 1]. These findings were suggestive of a renal mass with bleeding, possibly AML or renal cell carcinoma (RCC).

- NCCT abdomen and pelvis showing a hyperechoic exophytic mass (yellow arrow) in the left kidney, which contains fat and hemorrhagic densities. NCCT: non contrast computerised tomographic scan

The patient was admitted, and surgery was planned after correcting her anemia, as she remained stable. However, on the third day, she experienced giddiness, sweating, increased abdominal pain, and gross hematuria. Examination revealed a pulse of 126/min and blood pressure of 80/40 mmHg. She received intravenous fluid resuscitation, inotropic support and underwent emergency exploration and left radical nephrectomy. Intraoperatively, a markedly enlarged left renal mass with hematoma was observed, along with posterior adherence to the psoas fascia and approximately 150 cc of clot within the bladder. Radical nephrectomy and bladder clot evacuation were performed.

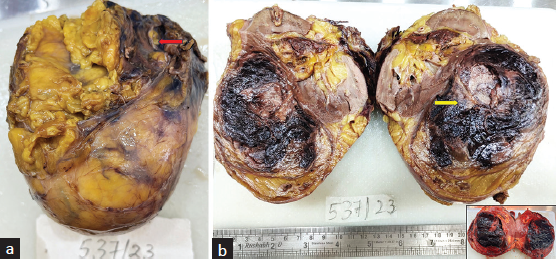

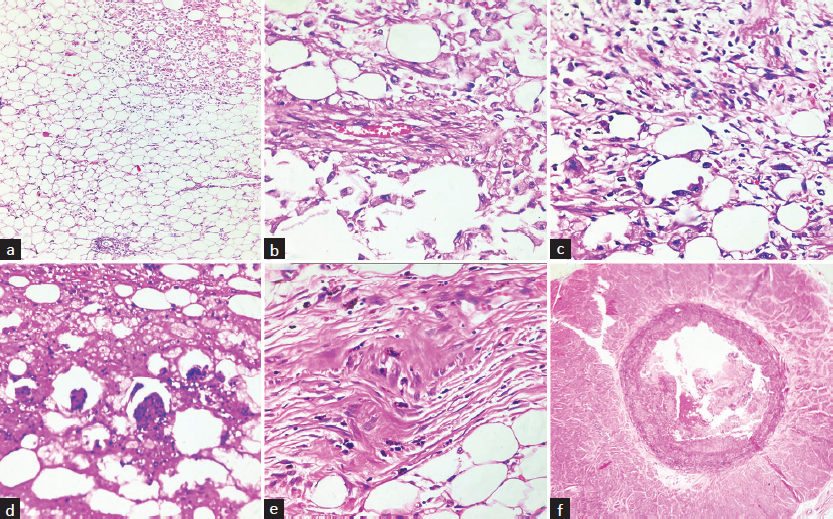

Histopathological examination of the nephrectomy specimen showed a hematoma near the hilar region but with an intact renal capsule and Gerota’s fascia. The cut surface revealed a relatively circumscribed grey-brown lesion with areas of hemorrhage and a fat component [Figure 2]. The renal artery cut margin displayed a thrombus. Ureteric and renal vein cut margins were unremarkable. Microscopic sections showed a benign tumor displaying a triphasic component consisting of mature adipose tissue, myoid cells with perivascular epithelioid differentiation, and some cells with reactive atypia. Extensive areas of necrosis and hemorrhage, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, fat necrosis, foamy histiocytes, and inflammatory cells were also observed. The renal artery cut margin showed a thrombus [Figure 3]. No malignant features were identified. Based on these findings, a final diagnosis of Renal AML with secondary changes was established.

- (a) Left nephrectomy specimen showing hematoma near the hilar region (red arrow); (b) Cut section showing grey-brown lesion with areas of hemorrhage and focal fat component (yellow arrow). Inset: Cut section – unfixed state.

- (a) Microphotograph showing sheets of mature adipose tissue with myoid component (right upper); (b) Dysmorphic blood vessels with thickened wall and perivascular epithelioid differentiation of myoid cells; (c) Myoid cells showing atypia with admixed fat cells; (d) Areas of fat necrosis with admixed inflammatory cells; (e) Fibrofatty areas showing pigment deposits; (f) Renal artery displaying thrombus formation.

Discussion

Renal AML was described by Grawitz in 1900 and is characterized by high vascularity and a variable composition of smooth muscle and adipose tissue.3 AMLs are often incorrectly referred to as hamartomas; however, they differ in that AMLs are true tumors, while hamartomas are disorganized collections of cells and tissues native to the location and are typically a result of trauma, infection, infarction, obstruction, or hemorrhage. In our case, there was no history of trauma. AMLs should not be confused with Grawitz tumors which include malignant RCC or hypernephroma.1

Epithelioid AML (EAML) is an uncommon variant described by Pea et al.4 in 1998, and it is considered potentially malignant. EAML primarily comprises sheets of epithelioid cells with a high degree of atypia and pleomorphism. Additionally, it may exhibit necrosis, making it challenging to differentiate from RCC. Literature suggests that EAML contains minimal or no fat, making diagnosis challenging. In our case, mature adipocytes were the dominant component, unlike EAML, and the epithelioid component was limited to the perivascular region.

Wunderlich syndrome (WS) is a surgical emergency and can be fatal if not promptly detected. The classic WS presentations are acute flank pain, a flank mass, and hypovolemic shock, collectively known as Lenk’s triad, described by German physician Carl Reinhold August Wunderlich. Renal AML is the leading cause of WS. Early detection of AML can prevent unnecessary high-risk surgeries. In this case, early detection allowed for immediate intervention, which saved the patient’s life and reduced morbidity.3 Management of AML depends on clinical manifestations, tumor size, number, growth pattern, and malignant potential.1 Symptomatic AML patients with evidence of growth should be considered for prophylactic embolization, which is the most successful nephron-sparing procedure. Nephrectomy is reserved for hemodynamically unstable patients or in cases of failed embolization.3 Given our patient’s bleeding lesion and unstable blood pressure, she underwent radical nephrectomy.

Early detection of AML-causing WS is critical to reduce patient mortality and morbidity. Diagnosing WS is challenging, especially when patients present with vague clinical features. A high index of suspicion for malignancy in such cases is essential. Correlation of clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings is crucial for an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Renal angiomyolipoma. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- [Google Scholar]

- A renal angiomyolipoma with a challenging presentation: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15:477.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A rare case of wunderlich syndrome secondary to bleeding renal angiomyolipoma. Surg Chron. 2021;26.:214-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal epithelioid angiomyolipoma: A case report and review of literature. Oman Med J. 2020;35:e178. doi: 10.5001/omj.2020

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]