Translate this page into:

A Case of Acute Renal Infarct Secondary to Protein S Deficiency

Corresponding author: Daniel Sam Mathews, Department of General Medicine, Dr. Jeyasekharan Hospital, Nagercoil, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: dxdanies@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Mathews DS, George N, Jeyasekharan R. A Case of Acute Renal Infarct Secondary to Protein S Deficiency. Indian J Nephrol. 2025;35:292-4. doi: 10.25259/ijn_522_23

Abstract

Renal infarction is an underdiagnosed and underreported condition with multiple etiologies. A 45-year-old man presented with acute pain in the right lumbar region, CT scan showed a wedge shaped, non-enhancing, hypodense lesion in the cortex of the upper pole of the right kidney- suggestive of infarct. A pro-thrombotic workup revealed a protein S deficiency and a heterozygous mutation for MTHFR gene. Protein S is a vitamin-K dependent plasma glycoprotein, the deficiency of which is associated with a hypercoagulable state, which in turn led to renal infarction in this patient.

Keywords

Hypercoagulable state

MTHFR mutation

Protein S deficiency

Renal infarction

Thromboembolism

Introduction

Renal infarction is underreported, with a reported incidence of 0.004% - 0.007%.1 It presents with flank pain, fever, nausea, vomiting, hematuria, and sudden rise in blood pressure or can mimic pyelonephritis, renal colic, or other diseases. Delayed or missed diagnosis results in irreversible injury to the kidneys. Timely revascularization can restore renal function.

Numerous etiologies lead to the development of renal infarction, but thromboembolism of cardiac origin atheromatous disease are the most frequent. Less common causes identified include hypercoagulable conditions (sickle cell disease, thrombophilia), cocaine misuse, trauma to the kidneys, malignancies, and renal vascular disease (vasculitis, fibromuscular dysplasia, spontaneous renal artery dissection, and dissecting aortic aneurysm). Rare causes include septic emboli in systemic candidiasis or emboli in Takotsubo syndrome. The underlying cause of renal infarction may be unknown despite extensive investigations, and these are labeled idiopathic renal infarcts.1 Only about 6% of the cases occur due to a hypercoagulable state.2

Case Report

A 45-year-old nonsmoker male presented with acute pain in the right lumbar region and fever, without associated chills, rashes, or joint pain. He had no nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, bowel or urinary symptoms, abdominal trauma, illicit drug use, or alcohol abuse. He gave no past history of renal stones, cardiac disease, or any chronic diseases or surgeries; there was no family history of blood disorders or malignancies.

On examination, he was conscious and oriented and the vital signs were normal. Mild tenderness was noted in the right lumbar region. Chest examination was within normal limits with no cardiac murmurs. The remaining physical evaluation was unremarkable.

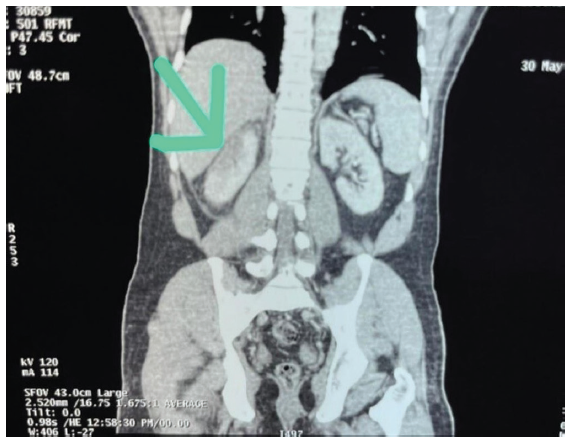

Laboratory results showed normal white blood cell (WBC) count, renal function, and urinalysis, with no growth on urine culture. Abdominal ultrasound showed an enlarged fatty liver and prostate. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen revealed a wedge-shaped, nonenhancing, hypodense lesion in the cortex of the upper pole of the right kidney, suggestive of infarct [Figure 1]. Renal artery Doppler was normal.

- CT abdomen showing infarct in the right kidney. The green arrow marks the wedge-shaped hypodense lesion in the cortex of the upper pole of the right kidney. CT = computed tomography.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram did not reveal atrial fibrillation, and the transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. A prothrombotic workup showed protein S deficiency and a heterozygous mutation in MTHFR gene.

The patient was started on dual antiplatelets and anticoagulants. The pain gradually subsided, and he was discharged with dual antiplatelets and oral anticoagulation. Follow-up revealed no further episodes, and renal function remained normal.

Discussion

Renal infarction is an unusual cause of abdominal pain. Based on autopsy data, a previous study estimated the incidence of renal infarction as 1.4%;3 however, only a few cases are reported due to the nonspecific presentation. The patients could even be asymptomatic, wherein the diagnosis is only identified incidentally on computed tomography (CT) scan.

WBC counts, C-reactive protein (CRP), alkaline phosphatase, and transaminases are often raised, though not consistently. Raised lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) is sensitive, but not specific.4 Raised serum creatinine may also be seen. Doppler has low sensitivity for identifying renal ischemia (10%).5 Renal artery angiography is the gold standard for diagnosis. It typically demonstrates wedge-shaped patches of hypoattenuation within the renal parenchyma, indicating perfusion defect. Etiological investigation requires electrocardiogram (ECG), Holter monitoring, echocardiography, CT angiography, hypercoagulability panel, and autoantibody assay.

A small percentage is caused by hypercoagulable diseases – antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), protein C, S, or factor V Leiden deficits, hyperhomocysteinemia, and polycythemia vera. In this patient, the underlying protein S deficiency was considered the likely cause of renal infarction. Protein S is a vitamin K-dependent plasma glycoprotein, acting as a cofactor for the activated protein C (APC) and tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) pathways. In addition, it inhibits the intrinsic tenase and prothrombinase complexes, thus having direct anticoagulant actions.6 Thus, patients deficient in protein S are at risk of developing recurrent thromboembolic events. Here, a heterozygous mutation in MTHFR manifested clinically, possibly contributing to the hypercoagulable state.

Treatment aims to restore blood flow to the kidneys early and prevent further embolic episodes. Treatment depends on the underlying etiology and needs to be tailored for each patient. It is mainly based on anticoagulants, and antiplatelets in select patients.

Given the nonspecific presentation, a high index of clinical suspicion should be maintained for early identification of renal infarction and its etiology, to avoid prolonged ischemia and irreversible renal damage.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acute renal infarction: A case series. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:392-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical characteristics and outcomes of renal infarction. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:243-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renal infarction: Statistical study of two hundred and five cases and detailed report of an unusual case. Arch Intern Med. 1940;65:587-94.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal infarction pathogenesis and atrial fibrillation: Case report and literature review. World J Nephrol Urol. 2016;5:11-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Idiopathic renal infarction: A new case report. Urol Case Rep. 2021;39:101752.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anticoagulant protein S—New insights on interactions and functions. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:2801-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]