Translate this page into:

A Long-Term follow-up Study of Lupus Nephritis in a Single Tertiary Care Centre

Address for correspondence: Dr. Ajay I. Rathoon, Department of Nephrology, SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Chennai, Tamil Nadu - 603 211, India. E-mail: rathoonajay@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Introduction:

Lupus nephritis (LN) is an immune complex glomerulonephritis, which is a very serious complication of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) as it can progress to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD).

Methods

In this study of 92 renal biopsy-proven LN, the patients were followed up for a minimum period of 2 years with a mean follow-up period of 5.4 ± 3.4 years.

Results

The mean serum creatinine of our study population was 1.4 ± 1.53. Our study population included 2 patients with class I lesions, 5 with class II, 22 with Class III, 53 with Class IV, and 10 with Class V lesions. Our therapeutic approach included only oral steroids for class I and class II lesions; for class III, IV, and V lesions, our approach included pulse steroids followed by oral steroids with either intravenous (IV) monthly cyclophosphamide (CYC) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). For maintenance, azathioprine or MMF were used along with low-dose oral steroids after 6 months of CYC or MMF. In CYC induction group containing 78 patients (84.7%), 66 patients (84.6%) attained remission (CR + PR), relapse in five patients (6.4%), ESRD on HD in five patients (6.4%), and death in two patients (2.6%).

Conclusion:

At the end of the study, in all groups, 79 patients (85.86%) were in remission (CR + PR), six patients (6.5%) were in relapse, five patients (5.4%) had reached the ESKD stage on HD, and two patients (2.2%) died.

Keywords

Cyclophosphamide

lupus nephritis

SLE

Introduction

Lupus nephritis (LN) is a frequent and potentially serious complication of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).[1] LN causes morbidity and mortality both directly and indirectly through the complications of its therapy. SLE is more common in females, with a ratio of 10:1, although males with SLE have the same rate of renal disease as females.[2] SLE peaks between the age of 15–45 years, and more than 85% of the patients are younger than 55 years of age. SLE is more commonly associated with severe nephritis in children and males and is milder in older adults.[3] Diagnosis of SLE is established by the presence of clinical and laboratory findings defined by EULAR/ACR 2019 criteria according to which ANA positive status is mandatory.[4]

In patients with SLE, abnormalities of immune regulation lead to a loss of self-tolerance, autoimmune responses, and the production of a variety of autoantibodies and immune complexes.[12] LN is an immune complex glomerulonephritis which is a very serious complication of SLE as it can progress to ESKD.[23]

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort descriptive study of 92 biopsy-proven LN patients who were followed up for a period ranging from a minimum of 2 years to a maximum of 15 years from January 2005 to December 2019. LN was defined by EULAR/ACR 2019 criteria, according to which ANA-positive status was considered mandatory. Only biopsy-proven LN cases were included. Pathologically, LN class was diagnosed according to ISN/RPS 2003 classification.[5]

Inclusion criteria

-

ANA at a titer of ≥1:80 on HEp-2 cell line platform at least once

-

Renal biopsy-proven LN

-

A minimum follow-up period of 2 years

-

All age groups included

Exclusion criteria

-

ANA-negative status

-

Follow-up period less than 2 years

-

LN Class VI

All the patients were followed up for a minimum of 2 years since the day of diagnosis of LN with renal biopsy. Clearance was obtained from the Institutional Human Ethical Committee.

Therapeutic protocol

For classes I and II, oral prednisolone at 1 mg/kg was given which was tapered to 10 mg/day within 6 months and continued during follow-up. For classes III, IV, and V, methylprednisolone pulse of 500 mg/day intravenously for 3 days followed by 1 mg/kg oral prednisolone, which was tapered to 10 mg/day over 6 months, and intravenous (IV) monthly cyclophosphamide (CYC) or mycophenolate was used as the primary induction agent after explaining the potential side effects. Our CYC protocol is explained in Figure 1.

- CYC Protocol

IV CYC was used at the dose of 500 mg/month for 6 months when patient weight was less than 40 kg and 750 mg/month if weight was more than 40 kg. The remaining patients who had a less severe form of disease or were not willing for CYC were started on mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) at a dose of 1.5 g/day as an induction agent in addition to steroids. Azathioprine at a dose of 1–2 mg/kg per day or MMF at a dose of 1 g/day were used as maintenance treatment along with low-dose oral steroid after 6 months of CYC or MMF.

Therapeutic response was assessed at 6th, 12th, 18th, and 24th month. KDIGO criteria were used to define complete remission, partial remission, no response, and relapse,[6] which are noted in Table 1. The primary endpoint of the study was to look for the percentage of remissions or relapses or ESKD on HD or death during the follow-up period.

| CONDITIONS | CRITERIA |

|---|---|

| Complete remission | Return of S.Cr to the previous baseline plus a decline in uPCR ≤500 mg/g |

| Partial remission | Stabilization (± 25%), or improvement of S.Cr, but not to normal, plus a ≥50% decrease in urine PCR. If there was nephrotic-range proteinuria (uPCR ≥3000 mg/g), improvement requires a ≥50% reduction in u PCR, and uPCR ≤3000 mg/g. |

| No remission | If not fitting into the above two criteria |

| Relapse | Creatine level <2.0 mg/dL, an increase of 0.20-1.0 mg/dL >2.0 mg/dL, an increase of 0.40-1.5 mg/dL and/or If baseline uPCR is: <500 mg/g, an increase to >1000 mg/g 500-1000 mg/g, an increase to >2000 mg/g >1000 mg/g, an increase of >2-fold |

Results

We analyzed 92 patients with baseline serum creatinine <1.40 mg/dL in 71 patients (77.2%) and >1.41 mg/dl in 21 patients (22.8%). Urine spot PCR of 0.5–3.0 in 63 patients (68.5%) and >3.0 in 29 patients (31.5%) were noted. Basic characteristics of the study population are listed in Table 2. Antiphospholipid antibodies (APLAs) were positive in seven patients (7.6%), thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) was seen in two patients (2.1%) who had class IV, and class transfer proved by repeat renal biopsy was seen in three (3.2%) patients.

| Characteristics | n (%) or mean±SD or Median (range) |

|---|---|

| n | 92 |

| Mean age | 37.1±12.5 |

| F: M | 81:11 |

| Proteinuria | 3.37±2.5 |

| Active Urine Sediments | 77 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.4±1.53 |

| Renal biopsy (ISN/RPS) | |

| Class I | 2 (2.2%) |

| Class II | 5 (5.4%) |

| Class III | 22 (23.9%) |

| Class IV | 53 (57.6%) |

| Class V | 10 (10.9%) |

| CYC induction | 78 (84.7%) |

| MMF induction | 7 (7.6%) |

| Mean follow-up duration | 5.4±3.4 years |

IV CYC induction was used in 78 patients (84.7%), and MMF induction in seven (7.6%). Only oral steroids were given for LN Class I and II, which was in seven patients (7.6%). The cumulative CYC dose used was 4.5 g in 49 patients (53.3%), 3 g in 27 patients (29.3%), and 1.5 g in two patients (2.2%), in whom due to infection further doses were not given. For maintenance, we used azathioprine along with low-dose oral steroids in 77 patients (81.5%), MMF along with low-dose oral steroids in nine patients (9.8%), and only oral steroids in eight patients (8.7%).

At the end of 6 months, 37 (40.2%) patients attained complete remission, 37 (40.2%) partial remission, and 18 (19.6%) no remission. At the end of 12 months, 54 (58.7%) patients attained complete remission, 24 (26.1%) partial, and 14 (15.2%) no remission. At the end of 18 months, 60 (65.2%) patients attained complete remission, 22 (23.9%) partial, and 10 (10.9%) no remission. At the end of 24 months, 65 (70.7%) patients attained complete remission, 20 (7.6%) partial, and seven (7.6%) no remission. A total of 85 patients (92.3%) attained remission at the end of 2 years of follow-up. One patient attained complete remission at the 26th month of follow-up. Response in various classes is shown in Figure 2.

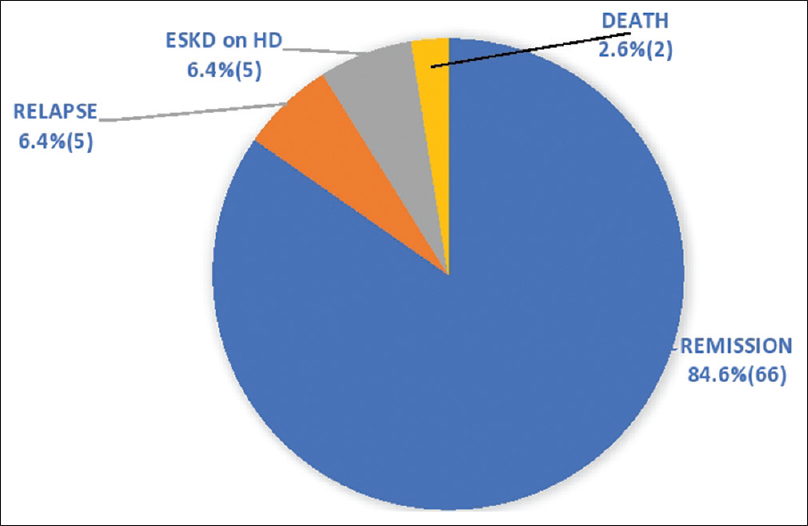

- Response at the end of 24 months in all classes

In patients with creatinine >1.4 mg/dL (21 patients), 10 (47.6%) patients attained complete remission, seven (33.3%) partial, and four (19%) no remission. In the CYC induction group of 78 patients (84.7%), at the end of 24 months, 55 (70.5%) patients attained complete remission, 17 (21.8%) partial, and 6 (7.7%) no remission, which is shown in Figure 3. At the end of the study, 66 (84.6%) patients attained remission, of which 51 patients complete and 15 partial, relapse in five patients (6.4%), ESKD on HD in five patients (6.4%), and death in two patients (2.6%), which is shown in Figure 4.

- At the end of 24 months in the CYC induction group

- At the end of the study in the CYC induction group

The mean duration at which remission was achieved was 7.4 ± 6.2 months. The range of attaining complete remission was 1–22 months with a mean of 7.4 ± 5.4 months. The range of attaining partial remission was 3–27 months with a mean of 9.5 ± 7.9. The mean duration of remission was 4.6 ± 3.3 years with a maximum remission period of 15 years.

Relapse was seen in 15 patients (16.3%), and 77 patients did not have relapse till the end of their follow-up period. We treated relapse by switching the maintenance drug from azathioprine to MMF. If a patient did not attain remission with this, then rituximab was used as a rescue drug. We used rituximab in 4 such patients, of which 3 patients attained remission and one patient did not attain remission and progressed to ESKD. Two patients presented with LN with TMA, who were started on IV CYC 750 mg/month six doses with five sessions of plasmapheresis, of which one patient improved and attained partial remission and the other patient progressed to ESKD on HD.

The minimum follow-up duration was 2 years, and maximum 15 years. The mean years of follow-up were 5.4 ± 3.4 years. Further, 51 patients (55.4%) had a follow-up duration of less than 4 years, 25 (27.2%) 5–9 years, and 16 (17.4%) 10–15 years. Of 92 patients in the study, 61 patients (66.3%) are still on regular follow-up. At the end of the study, 79 (85.86%) patients were in remission (CR + PR), 6 (6.5%) in relapse, 5 had reached the ESKD stage on HD, and 2 (2.2%) died.

Adverse events such as pneumonia were seen in 4 patients, acute bronchitis in 7, fungal skin infection in 2, herpes zoster in 5, leukopenia in 2, abscess in 1, and deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) in 1 patient.

Discussion

This is a single-center retrospective cohort study that was conducted in a tertiary care center in South India. We included all patients who were ANA positive with a renal biopsy-proven LN and a minimum follow-up period of 2 years to a maximum period of 15 years. The male:female ratio in our study population was 1:7.3. We defined remission, relapse, and treatment failure according to the KDIGO guidelines.[6]

In our study, we used IV CYC at a dose of 500 mg/once a month for 6 months when patient weight was less than 40 kg and 750 mg/once a month for 6 months when patient weight was more than 40 kg for class III, IV, and V lesions compared to NIH regimen where CYC dose of 0.5–1 g/m2 was given once a month for 6 months followed by quarterly for 2 years,[7] and according to Euro-lupus regimen, a CYC dose of 500 mg was given once in 2 weeks for 3 months irrespective of the weight of the patient.[8] In these two regimens, CYC was not used in class V patients.

Our CYC protocol was used in 78 (84.7%) patients out of the total 92 patients of the study population, of which 66 (84.6%) attained remission; relapse was noted in five (6.4%) patients, 5 (6.4%) progressed to ESKD on HD, and 2 (2.6%) died. Of 22 class III patients, CYC was used in 19 patients, of which 18 (94.7%) patients attained remission. Of 53 class IV patients, CYC was used in 51 patients, of which 40 (78.4%) patients attained remission.

Our protocol had a better remission rate of 84.6% with CYC when compared to ALMS multicenter study, where the remission rate was 56.2% in the MMF group and 53.0% in the CYC group.[9] In the American study by Ginzler et al.[10] published in 2005, the remission rate for MMF was 52.1% and for CYC was 30.4%, rates which were less when compared to our study. In the NIH trial, the methylprednisolone and CYC group attained a remission rate of 85%,[7] and in a multicenter Chinese study,[11] the remission rates for CYC as per NIH protocol was 82.1%, which was similar to our results.

Our cumulative CYC dose range (3–4.5 g), is less than the NIH regimen and the same as or slightly higher than the EURO-LUPUS regimen. However, our duration of treatment was over 6 months when compared to 3 months in the EURO-LUPUS trial.[8] Our CYC regime exposes the patients of LN to a lower cumulative dose of CYC over a longer duration; thus, the side effects, especially infections and leukopenia, were less without sacrificing efficacy. Comparison of basic characteristics and outcome of various studies is listed in Table 3. The adverse events in our study and their comparison with other studies are listed in Table 4.

| Variable | ELNT low-dose CYC arm8] | Jayaprakash et al.[11] | Manish Rathi et al.[12] CYC arm | Our study CYC arm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 44 | 41 | 50 | 78 |

| Mean age | 33±12 | 27.1±9.24 | 30.6±9.5 | 35.1±11.5 |

| F: M | 41:3 | 37:4 | 45:5 | 67:11 |

| Race | Caucasian | South Asian | South Asian | South Asian |

| Proteinuria | 24-h urine protein 3.04±2.39 g | Urine PCR 4.99±2.13 | Urine PCR 3.0 | Urine PCR 3.45±2.6 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.15±0.66 | 2.24±1.45 | 0.87 | 1.5±1.6 |

| Renal Biopsy | ||||

| Class III | 11 (25) | 7 (17.1%) | 6 (12%) | 19 (24.3%) |

| Class IV | 31 (70.45%) | 34 (82.9%) | 30 (62%) | 51 (65.4%) |

| Class V | 2 (4.5%) | - | 14 (28%) | 8 (10.3%) |

| Pulse MP dose (mg) | 750 | 1000 | 750 | 500 |

| Cumulative CYC Dose (g) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3-4.5 |

| Dosing of CYC | Fortnightly | Monthly | Fortnightly | Monthly |

| Induction duration | 3 months | 6 months | 3 months | 6 months |

| Renal Remission | 31 (71%) | 27 (65.9%) | 31 (62%) | 66 (84.6%) |

| CR | - | 13 (31.7%) | 15 (30%) | 51 (77.3%) |

| PR | - | 14 (34.1%) | 16 (32%) | 15 (22.7) |

| Death | 2 (4.5%) | 5 (13.8%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (2.6%) |

| Adverse Event | ELNT low-dose CYC arm[8] (n=44) | Jayaprakash et al.[11](n=41) | Manish Rathi et al.[12] CYC arm (n=50) | Our study CYC arm (n=78) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Acute Bronchitis | - | - | - | 7 |

| UTI | 5 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| Fungal Skin infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Herpes zoster | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Esophageal candidiasis | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Abscess | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Sepsis | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Leukopenia | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| DVT | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

The limitations of this study are that it was a single-center observational study with no control group. The MMF induction population was very small. The study population belonged to a single ethnic group.

Conclusion

In our study according to the treatment protocol discussed above, we reached a comparable or even better remission rate with a very less toxicity profile. However, a larger, multicenter, multi-ethnic, randomized, controlled study is required to provide stronger evidence.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Understanding the epidemiology and progression of systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39:257-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2020. In: Definitions. Qeios. Available from: https://www.qeios.com/read/definition/14382. [Last accessed on 2021 May 29].2020. Available from: https://www.qeios.com/read/definition/14382

- The ISN/RPS 2003 classification of lupus nephritis: An assessment at 3 years. Kidney Int. 2007;71:491-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis: The Euro-Lupus nephritis trial, a randomized trial of low-dose versus high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide: Immunosuppressive therapy in lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2121-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide for induction treatment of lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1103-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mycophenolate Mofetil or Intravenous Cyclophosphamide for Lupus Nephritis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2219-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- End of induction treatment outcomes with a novel cyclophosphamide-based regimen for severe lupus nephritis: Single-center experience from South India. Indian J Rheumatol. 2020;15:100-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of low-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide with oral mycophenolate mofetil in the treatment of lupus nephritis. Kidney Int. 2016;89:235-42.

- [Google Scholar]