Translate this page into:

Chronic type B aortic dissection in association with Hemolyticuremic syndrome in a child

Address for correspondence: Dr. Dinesh Gera, Department of Nephrology and Clinical Transplantation, Institute of Kidney Diseases and Research Centre, Dr. H.L. Trivedi Institute of Transplantation Sciences, Civil Hospital Campus, Asarwa, Ahmedabad - 380 016, Gujarat, India. E-mail: dineshgera@ymail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Aortic dissection (AD) is a potentially life-threatening medical emergency usually encountered in the elderly. Here, we report a 9-year-old child who was incidentally detected to have asymptomatic chronic type B dissecting aneurysm of aorta when he presented with relapse of Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) without any genetic abnormalities like Marfan or Ehler-Danlos syndrome. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of AD associated with HUS in a child without any known associated genetic or inherited risk factors.

Keywords

Child

dissecting aneurysm of aorta

hemolytic uremic syndrome

hypertension

Introduction

A population based longitudinal study over a period of 27 years, from Hungary reported annual incidence of aortic dissection (AD) of 2.9/100,000 population.[1] The international registry of acute aortic dissection (IRAD) reported mean age of 63 years, 63.5% affecting male, with male:Female ratio of 2:1 and 62.3% were of type A dissection.[2] In the younger population incidence is still more rare and usually has some associated special risk factor or positive family history. Out of a total 1085 patients reported in two large series of dissecting aortic aneurysms 38 (3.5%) occurred in persons 19 years of age or younger.[3] In IRAD data 72% had a history of hypertension as the most important modifiable risk factor.[2]

Since acute AD of ascending aorta is potentially life-threatening emergency with the mortality rate of 1-2% per h for 1st 48 h in untreated patients.[2] Immediate suspicion of possibility from symptomatology, clinical presentation and knowledge of pre-disposing risk factors, after hemodynamic stabilization, the diagnosis should be persuaded by optimal uses of available imaging modalities depending on patient's condition and patient should be shifted at earliest to nearest aortic center.

Case Report

A 9-year-old male child weighing 23.5 kg was admitted in December 2012 with complains of vomiting, oliguria, edema face and pallor for 4 days. There was no history of fever, diarrhea and frank hematuria, pain in abdomen, pain in chest, dyspnea, dysuria or joint pain. Child had a history of similar complains in February 2012 when he was admitted in our institute and was diagnosed to have hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). He had undergone six sessions of plasma exchanges and alternate day hemodialysis (HD) during his stay in hospital. He was discharged on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) with tablet nifedipine- retard 10 mg twice-a-day, tablet clonidine (0.1 mg) half-tablet twice-a-day and tablet sodium bicarbonate (500 mg) twice-a-day. In May 2012, his CAPD catheter was removed when his urine output was increased to 1.5 L/day and he was maintaining serum creatinine of 0.6 mg/day. He was continued on anti-hypertensive medication and he was on monthly follow-up evaluation.

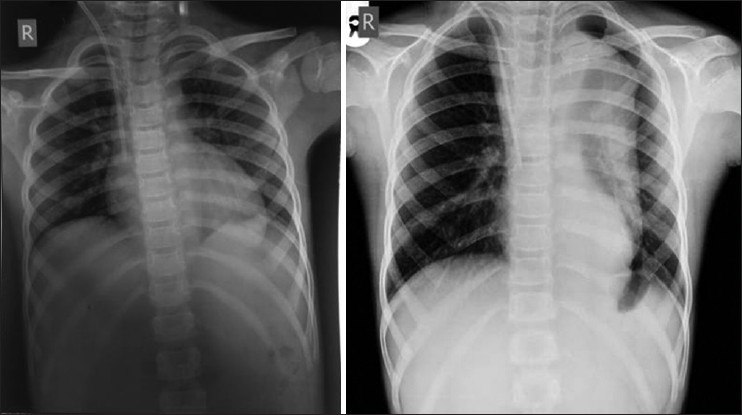

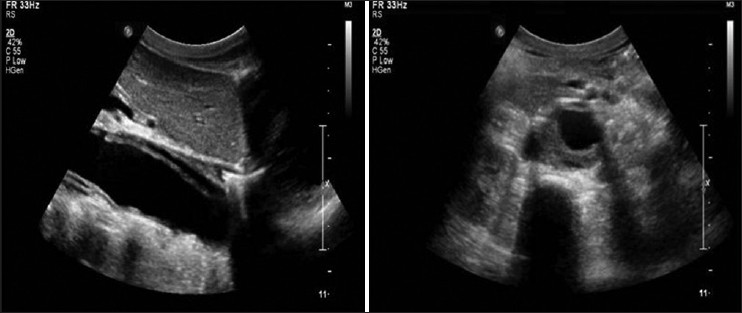

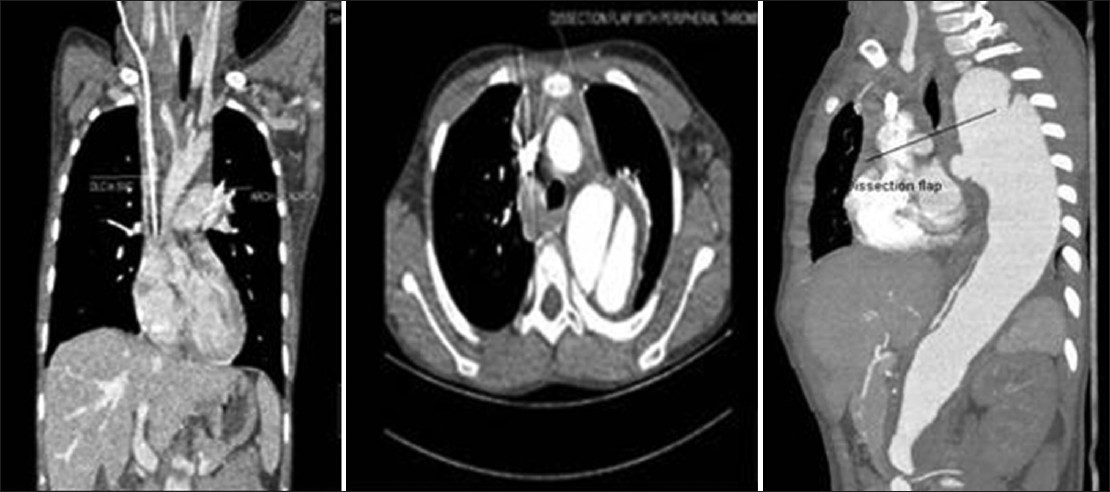

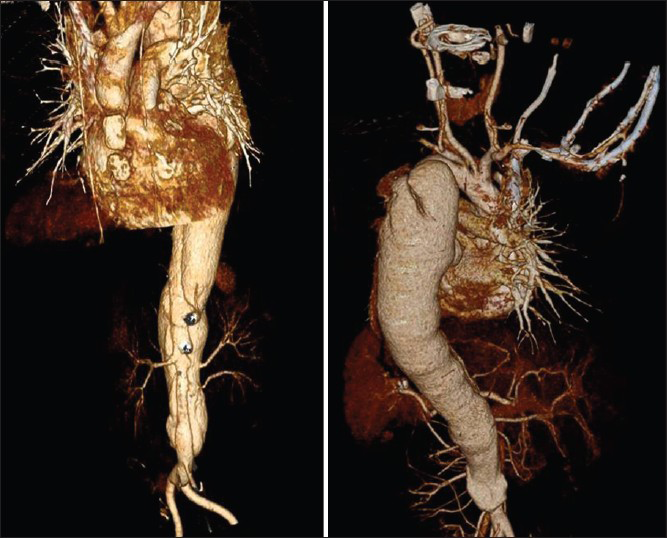

On examination, child was well-built, well-nourished, intelligent with normal skin texture without any bruises on joints, having a height of 130 cm, upper segment 66 cm, lower segment 64 cm with an arm span of 126 cm without any abnormal phenotypic feature. His pulse was 100 beat/minhaving bilateral symmetry, blood pressure 200/100 mm of Hg in both upper limb in a sitting position and 206/100 mm of Hg in both lower limbs in lying down position. Femoral, popliteal and dorsalis pedis arteries were equally palpable on both sides. There were no parasternal murmurs on auscultation. Respiratory system was normal on examination and fundus examination was normal. On investigation, urine examination showed albumin +2, sugar nil, 30-40 dysmorphic red blood cells/high power field, hemoglobin 13.1 g/dL, platelet-100,000/cm, peripheral smear showed many schistocytes suggestive of hemolysis. Direct Coomb's test was negative. Blood urea was 154 mg/dL, serum creatinine-5.36 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 1317 U/L, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein 2.7 μg/mL (reference range 1-3 μg/mL), serum sodium 138 meq/L, serum potassium 4.8 meq/L, serum C3 level 68 mg/dL (reference level 90-207 mg/dL) serum C4 level 30 mg/dL (reference level 17.4-52.4 mg/dL), ultrasound abdomen showed right kidney 8.4 cm × 3.1 cm and left kidney 8.7 cm × 3.1 cm with increased echogenicity without stone or hydronephrosis. Right internal double lumen catheter (DLC) was inserted for management and X-ray chest was taken to confirm the position of DLC, which showed widening of the mediastinum and well-defined soft-tissue opacity in left paratracheal and left paracardiac region and shadow of aortic knob and descending aorta was not visualized. Contour of right cardiac border was normal and catheter tip was in the right atrium. X-ray chest of previous admission was brought out and it was showing normal cardiac shadow [Figure 1]. Transthoracic echocardiography showed normal aortic valve, ascending aorta and cardiac chambers. Doppler of the abdominal aorta and computed tomography with contrast (CT angio) showed dissection of aorta arising distal to the left subclavian artery and extending up to bifurcation of the aorta with a diameter of descending thoracic aorta 4 cm and abdominal aorta 38 mm with central patent lumen of 2.4 cm and intimal flap within with false lumen diameter of 0.4 cm with partial peripheral thrombus in true lumen [Figures 2 and 3]. CT angio showed two left renal arteries and one right renal artery of normal caliber without any aortic branch vessel involvement [Figure 4]. As the child is asymptomatic and has type B dissection of the aorta with a diameter of less than 4 cm, he was started on conservative management with beta blocker and other anti-hypertensive medications along with CAPD and other supportive medications on surveillance monitoring. For his relapse of HUS child was given alternate day hemodialysis and five sessions of plasma exchange each of 1L volume when his platelet count reached 320,000/cu mm and LDH 240 U/L. His oliguria persisted to 300 mL/day and serum creatinine remained 4.28 mg/dL. Renal biopsy was performed, which showed acute on chronic HUS [Figure 5]. CAPD catheter was again inserted and peritoneal dialysis cycles were restarted and his anti-hypertensive requirement included tablet atenolol (50 mg/day), tablet minoxidil (2.5 mg twice a day), tablet prazosin (slow release) (5 mg/day), tablet losartan (50 mg twice a day) and he is maintaining blood pressure of 110/70 mm of Hg at the time of discharge. His father was trained to measure blood pressure at home and keeps a record of same and he has been informed about warning symptoms and child is prohibited from weight lifting.

- X-ray chest on initial admission and at the time of relapse of Hemolytic uremic syndrome, second X-ray shows well-defined soft-tissue opacity in left paratracheal and left paracardiac region and shadow of aortic knob and descending aorta not visualized

- Doppler study - Longitudinal section view showing dissection flap within aorta separating true lumen and false lumen and peripheral thrombus in true lumen

- Computed tomography angio of coronal and axial view-showing normal ascending aorta, dissection starting after left subclavian artery extending up to bifurcation of the aorta with dissection flap and peripheral thrombus in true lumen

- 3D representation of aorta showing dissection starting after left subclavian artery extending to bifurcation of the aorta with the site of intimal flap and renal arteries of normal caliber on both sides (left side two renal arteries, right side one renal artery)

- Glomeruli show wrinkled and duplicated basement membranes and congested capillary lumina with red blood cells and fibrin thrombi. Interlobular artery shows marked mucointimal proliferation with subintimal focal fibrin deposition

Discussion

Thrombotic microangiopathy defines the characteristic pathologic changes of HUS. Kidneys are the main target organs. In the acute phase renal biopsy shows glomerular or arteriolar fibrin rich thrombi in different distribution and severity, whereas subendothelial fluff is seen after days or weeks.[45] Large vessels involvement is not described in HUS, (rather not studied in HUS), but our patient presented with type B AD at the time of relapse of HUS that is why we intend to report this unusual association. He was on anti-hypertensive medication after the first attack of HUS, but his blood pressure was out of control at the time of relapse. His hypertension could be contributory to causation of AD. That even in adults also a minority of patients with hypertension get a dissection suggests that a structural weakness of the arterial wall is also necessary to develop dissection.[6] In pediatrics, AD in general is rare and in the absence of genetic, hereditary or congenital cardiac or aortic defect it is extremely rare. Our patient didn’t have a history of diarrheal prodrome. Moreover, recurrent nature and protracted course of the disease points to an atypical nature of HUS.

Various hereditary diseases with abnormal connective tissue like Marfan syndrome, Ehler-Danlos syndrome type IV are commonly associated with AD in young.[37] Certain congenital cardiac defects such as bicuspid aortic valve, coarctation of aorta, annuloaortic ectasia, history of balloon angioplasty for coarctation, fibromuscular dysplasia are additional risk factors for dissection in young.[237] Advanced age, chronic hypertension and atherosclerosis are important risk factors in adults.[89]

Stanford's classification (Daly) of AD is more widely used. Dissection that involves ascending aorta is classified as type-A regardless of the site of primary intimal tear and all other dissections not involving the ascending aorta as type B.[10] The dissection is considered “acute” when the diagnosis is made within 14 days of onset and it is considered “chronic” if >14 days have elapsed since the acute event.[611]

Acute type A AD is a surgical emergency requiring early surgical repair of aorta.[11] Acute type B dissection is defined to be complicated type B dissection by the presence of visceral, renal or limb ischemia, rupture, refractory pain or uncontrollable hypertension is the key factor that determines the necessity of endovascular intervention.[111213] Our patient was asymptomatic and didn’t have any of these complications. Series have shown that drug treatment alone can result in 78% 3 year survival in uncomplicated type B dissection.[14] Current guidelines deem this a difficult benchmark to surpass by endovascular management.[14] Endovascular management is increasingly possible with low mortality[15] and its role in uncomplicated type B dissection will be clarified by the result of acute dissection stent grafting or best medical treatment trial (NCT00742274).[12] Until results are available, medical management remains the gold standard.[1214]

Whatever treatment has been given initially, they need best blood pressure control and close surveillance for early detection of any complication. Regular out-patient visit at 3 month interval during 1st year after discharge and yearly thereafter is recommended.[1216] Entire length of the aorta is to be screened by imaging.[12]

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, it is the first reported case of type B AD in a child in association with HUS who does not have any other genetic pre-disposing factor. It may be possible that weakness of aorta caused by HUS in combination with hypertension may have led to AD. Finding of widened mediastinum on chest radiograph warrants immediate further imaging to rule out aortic aneurysm or dissection.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- The international registry of acute aortic dissection (IRAD): New insights into an old disease. JAMA. 2000;283:897-903.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dissecting aortic aneurysm in childhood and adolescence. Case report and literature review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1981;20:578-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aortic dilation, dissection, and rupture in patients with turner syndrome. J Pediatr. 1986;109:820-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histologic changes in the normal aging aorta: Implications for dissecting aortic aneurysm. Am J Cardiol. 1977;39:13-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk factors for aortic dissection: A necropsy study of 161 cases. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:849-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aortic dissection: New frontiers in diagnosis and management: Part I: From etiology to diagnostic strategies. Circulation. 2003;108:628-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term survival in patients presenting with type B acute aortic dissection: Insights from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. Circulation. 2006;114:2226-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expert consensus document on the treatment of descending thoracic aortic disease using endovascular stent-grafts. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(Suppl 1):S1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chronic aortic syndrome: How to follow patients, which complications and when to treat? Presse Med. 2011;40:88-93.

- [Google Scholar]