Translate this page into:

Clinical Transplant Kidney Function Loss Due to Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth

Corresponding author: Tomoo Kise, Division of Paediatric Nephrology, Okinawa Prefectural Nanbu Medical Centre, Children’s Medical Centre, Haebaru, Japan. E-mail: tomookise0618@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Kise T, Uehara M. Clinical Transplant Kidney Function Loss Due to Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Indian J Nephrol. doi: 10.25259/ijn_535_23

Abstract

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a clinical syndrome involving gastrointestinal symptoms caused by the presence of excessive bacteria in the small intestine. SIBO often leads to diarrhea and poses diagnostic and treatment challenges. Here, we report about a renal transplant recipient who experienced diarrhea-induced hypovolemic shock due to SIBO, necessitating the reintroduction of dialysis, and aim to provide insights to aid health-care providers in diagnosing and managing severe diarrhea in this specific patient group. A 14-year-old boy, who had undergone renal transplantation at the age of 2 years, experienced severe, recurring diarrhea leading to hypovolemic shock. The patient underwent volume loading and continuous hemodiafiltration. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy findings suggested Whipple’s disease. Antibiotics were initiated; however, the diarrhea did not improve. Examinations for infectious enteritis and food allergies yielded negative results. The diarrhea improved with rifaximin (RFX), but recurred repeatedly after its discontinuation. Antibiotic rotation, wherein RFX, amoxicillin hydrate and potassium clavulanate, ciprofloxacin, and RFX were administered in this order for 4 weeks each, improved the diarrhea. A lactulose breath test performed immediately before the second RFX course yielded negative results. The patient’s condition was diagnosed as SIBO based on the clinical course, although the diagnostic criteria were not met. SIBO should be considered in cases of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with transplanted kidneys. Antibiotic rotation should be considered for SIBO treatment in immunosuppressed patients.

Keywords

Antibiotic rotation

post-kidney transplant patient

severe diarrhea

small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

immunosuppression

Introduction

Diarrhea is the most common gastrointestinal symptom in kidney transplant patients and is often caused by infections or drugs.1 Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a clinical syndrome characterized by gastrointestinal symptoms due to excessive bacterial population within the small intestine.2 Herein, we report about a renal transplant recipient who experienced diarrhea-induced hypovolemic shock due to SIBO, necessitating dialysis reintroduction.

Case Report

A 14-year-old boy was admitted to our intensive care unit with hypovolemic shock secondary to diarrhea. He underwent renal transplantation at 2 years of age owing to bilateral hypoplastic/dysplastic kidneys. He had chronic diarrhea and anorexia for 2 years before admission. Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed no abnormalities. He was prescribed loperamide and esomeprazole based on his symptoms. After the onset of chronic diarrhea, his weight decreased from 38 to 30 kg over 2 years. Regarding chronic rejection, his transplanted kidney function, indicated by the estimated glomerular filtration rate, was 40 mL/ min/1.73 m2. The immunosuppressants administered include methylprednisolone 4 mg every alternate day, cyclosporine 120 mg/day, and mycophenolate mofetil 750 mg/day.

On admission, the patient’s vital statistics included weight, 25.8 kg; height, 152 cm; body temperature, 36.5°C; blood pressure, 98/60 mmHg; heart rate, 62 beats/min; and oxyhemoglobin saturation, 88%. Clinical findings revealed drowsiness, inability to walk, sunken eyes, clear breath sounds, absence of heart murmurs, flat abdomen with increased bowel sounds, and cold limbs. Laboratory data indicated renal dysfunction, hypokalemia, metabolic acidosis, and anemia.

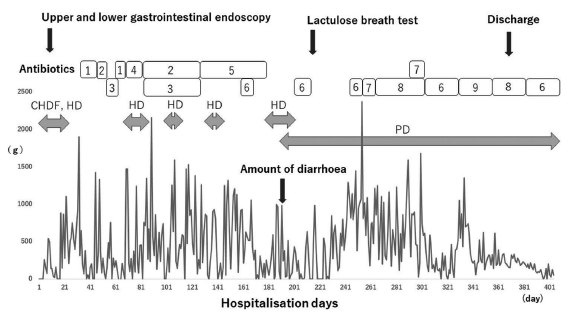

The patient underwent volume loading and continuous hemodiafiltration in the intensive care unit. Whipple’s disease was suspected based on duodenal findings from upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, and intravenous ceftriaxone (CTRX) was initiated [Figure 1]. His diarrhea was initially ameliorated, but subsequently worsened. Transitioning from CTRX to doxycycline (DOXY) led to no improvement. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), CTRX, meropenem, DOXY + HCQ, and ampicillin were administered in that order, yet the diarrhea persisted. The patient could not eat and received total parenteral nutrition. In addition, he was sleep deprived because of nighttime episodes of diarrhea. Examinations for infectious enteritis and food allergies yielded negative results. Hemodialysis was then switched to peritoneal dialysis.

- Progress after hospitalization. Numbers in the antibiotics column: 1. ceftriaxone, 2. doxycycline, 3. hydroxychloroquine, 4. meropenem, 5. ampicillin, 6. rifaximin, 7. metronidazole, 8. ciprofloxacin, 9. amoxicillin hydrate and potassium clavulanate. CHDF = continuous hemodiafiltration, HD = hemodialysis, PD = peritoneal dialysis.

As pediatric nephrologists with 20 years of experience, we consulted a pediatric gastroenterologist regarding the patient’s diagnosis and treatment. A 10-day regimen of rifaximin (RFX) was initiated for SIBO treatment; loperamide and esomeprazole were discontinued. Diarrhea improved 10 days after RFX initiation. Since diarrhea recurred after RFX discontinuation, three RFX courses were administered. A lactulose breath test performed immediately before the second RFX course yielded negative results. Ten days after initiating the third RFX treatment, diarrhea worsened, rendering the patient unable to consume food. RFX was replaced with metronidazole (MTR), but diarrhea worsened. Subsequently, MTR was substituted with ciprofloxacin (CPFX). Approximately 1 week after switching to CPFX, the diarrhea subsided, allowing the patient to resume eating. Following 4 weeks of CPFX treatment, CPFX and MTR were administered for 2 weeks. Owing to worsening diarrhea, CPFX and MTR were substituted with a fourth RFX course. Approximately 2 weeks after RFX initiation, the diarrhea decreased. RFX was administered for 4 weeks, followed by amoxicillin hydrate and potassium clavulanate for 4 weeks and CPFX for 4 weeks. The patient was discharged on hospitalization day 362. After CPFX, the fifth course of RFX was administered for 4 weeks and then discontinued. After discharge, the patient experienced solid and stable stools, occurring three to four times daily. Six months after discharge, the patient’s weight improved to 40 kg. Even after the diarrhea subsided, the renal function did not improve, and peritoneal dialysis was continued. All immunosuppressants were discontinued after discharge.

Discussion

In SIBO treatment, antibiotic rotation and elimination of exacerbating factors help improve diarrhea. Several antibiotics are used, with an administration period of 5–28 days and an efficacy rate of 30%–100%.2 RFX is the most widely studied antibiotic for SIBO.3 Despite its effectiveness, relapse is common, with 44% of patients experiencing relapse within 9 months of the initial treatment.3 Our patient had initial RFX efficacy, with repeated relapses, prompting antibiotic rotation every 4 weeks to prevent recurrence. The antibiotic rotation reported by Tauber et al.4 did not include RFX and had a 57% efficacy rate. Antibiotic rotation should be considered in SIBO treatment for immunosuppressed patients.

SIBO risk factors include hypochlorhydria, pancreaticobiliary disease, motility disorders, anatomic disorders, and immune disorders.5 In addition, chronic renal dysfunction worsens the intestinal flora.6 In our patient, the use of immunosuppressants, proton pump inhibitors, and antidiarrheal agents worsened the intestinal flora and caused SIBO.

In our patient, although the diagnostic criteria were not met, SIBO was diagnosed based on clinical findings. SIBO is diagnosed using a small intestinal aspirate culture or lactulose or glucose breath test.2 However, intestinal culture is invasive, and breath tests have a sensitivity of only 31%–68% for lactulose and 20%–93% for glucose when compared to cultures of the small bowel.2 Improved SIBO diagnostic methods are needed. Nevertheless, SIBO should be considered in cases of gastrointestinal symptoms in kidney transplant patients.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Nanbu for supporting diagnosis and treatment.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Etiological spectrum of infective diarrhea in renal transplant patient by stool PCR: An indian perspective. Indian J Nephrol. 2021;31:245-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- ACG Clinical Guideline: Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:165-78.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Clinical features and therapeutic management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2019;10:e00078.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and predictors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:S82-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2021;50:463-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney Int. 2013;83:308-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]