Translate this page into:

Collapsing Glomerulopathy Superimposed on Diabetic Nephropathy

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is characterized by gradually progressive renal failure and proteinuria. Various types of nondiabetic kidney diseases may superimpose on DN, and affect the natural course, prognosis, and management. Collapsing glomerulopathy (CG) is a form of glomerular proliferative injury, characterized by rapid progression and associated with poor prognosis. CG may be idiopathic or secondary to other causes, and it has also been described with other forms of glomerular diseases. The association of CG with DN has not been reported widely. We report on a patient with DN who has undergone renal biopsy due to massive proteinuria and rapid loss of renal function. Renal biopsy was suggestive of CG superimposed on DN. He was treated conservatively, however, progressed to end-stage renal disease rapidly.

Keywords

Collapsing glomerulopathy

diabetic nephropathy

focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

Introduction

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD). It is slowly progressive over the years and characterized by progressive increase in proteinuria and decline in glomerular filtration rate. Various forms of nondiabetic kidney diseases (NDKD) may occur alone or superimpose on DN and may alter the management and prognosis. Collapsing glomerulopathy (CG) is a severe form of glomerular proliferative injury characterized by rapid progression and associated with poor prognosis. CG may be idiopathic or secondary to other causes, and it has also been described with other types of glomerular diseases. The association of CG with DN has not been reported widely. Till date, only one case series of CG in association with DN has been described.[1] Here, we present a patient with long-standing DN, who has undergone renal biopsy due to rapid deterioration in renal function and increase in proteinuria. Renal biopsy was suggestive of CG superimposed on DN.

Case Report

A 56-year-old man, Type 2 diabetic for 15 years, hypertensive and having chronic kidney disease (CKD) from 5 years, presented with a 2-week history of malaise, anorexia, nausea, pedal edema, and oliguria. He was under regular follow-up for the management of CKD, presumed as DN, and was on angiotensin receptor blocker and insulin therapy. One month before his illness, his serum creatinine was 2.1 mg/dl, urine analysis showed 1+ albumin with bland urine sediment, and 24 h urine protein excretion was 1.2 g/day. On examination, he had pallor, pitting pedal edema, and high blood pressure (160/90 mm Hg). Ocular fundus examination revealed nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. Rest of the systemic examination was unremarkable.

The laboratory findings revealed hemoglobin of 9.2 g/dl, serum creatinine of 5.4 mg/dl, and serum albumin of 2.2 g/dl. His urine examination showed 4+ albumin, 10–12 erythrocytes/hpf, and 15–20 pus cells/hpf. Spot urine protein creatinine ratio was high (9.3). Serology for hepatitis B and C, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), anti-nuclear antibody, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody was negative. Serum complement levels and anti-streptolysin O titer were normal. Serum protein electrophoresis was not suggestive of monoclonal gammopathy. Urine culture did not show any bacterial growth. Ultrasonography and Doppler revealed increased resistive index in segmental arteries. We suspected an NDKD superimposed on DN; and hence, renal biopsy was performed.

Renal biopsy findings

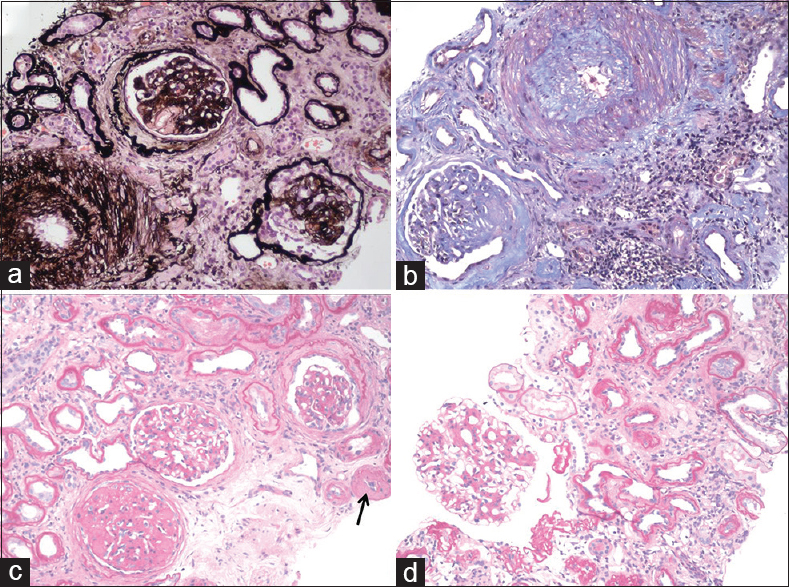

On light microscopy, 10 out of 19 glomeruli were partially to completely sclerosed with hyalinosis lesions, periglomerular fibrosis, and ischemic changes. One glomerulus (about 10% of nonsclerosed glomeruli) showed the global collapse of the tuft with hyperplasia of the overlying podocytes. The other glomeruli showed periodic acid–Schiff positive mesangial widening with no increase in cellularity. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IF/TA) was up to 50% of the cortex sampled. Mild lymphocytic infiltrate was noted around the atrophic tubules. Arteriolar hyalinosis (AH) was seen in many vessels, and arteries showed intimal fibrosis focally exceeding the thickness of media [Figure 1]. The pathological lesions were scored according to Tervaert et al.[2] Immunofluorescence (six glomeruli) was negative for immunoglobulins and complement. Kidney biopsy showed features of advanced DN (glomeruli: class-IV; scores of interstitial inflammation-1/2, IF/TA-2/3, AH-2/2, arteriosclerosis [AS]-2/2) with superimposed CG. On further evaluation, we could not find any secondary causes of CG. He was continued on supportive treatment. However, his renal function worsened further over the next 15 days to reach ESRD and he was prescribed regular hemodialysis.

- (a) Collapsed glomerular tuft with hyperplasia of overlying podocytes in the bottom right glomerulus (methenamine silver, ×100), (b) Large artery with prominent intimal sclerosis (Masson's trichrome, ×100), (c) Arteriolar hyalinosis (arrow), (d) Glomerulus with mesangial widening (c and d: PAS, ×100)

Discussion

CG is a distinct pathologic entity characterized by segmental or global collapse affecting at least one glomerulus with overlying hypertrophy or hyperplasia of visceral epithelial cells (pseudo-crescents), and tubulointerstitial disease (sometimes with microcystic transformation).[345] There is a growing list of disorders that are associated with CG [Table 1].[45]

| Categories | Causes |

|---|---|

| Infections | HIV, HCV, CMV, EBV, HTLV-1, parvovirus B19, Campylobacter, pulmonary tuberculosis, visceral leishmaniasis, filariasis, Loa loa |

| Autoimmune diseases | Adult still’s disease, MCTD, SLE, lupus-like syndrome, giant cell arteritis |

| Drug induced | Interferon, pamidronate, CNI, anabolic steroids, valproic acid |

| Malignancies | Acute monoblastic leukemia, hemophagocytic syndrome, multiple myeloma |

| Post-transplantation | De novo, recurrent, acute vascular rejection |

| Genetic disorders | Action myoclonus-renal failure syndrome, mandibuloacral dysplasia, mitochondrial cytopathy, familial, sickle cell anemia, MYH9, and APOL1 gene polymorphisms |

| Idiopathic | |

| Others | Severe hyaline arteriopathy, TMA, permeability factor, Guillain-Barre syndrome |

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, HCV: Hepatitis-C virus, CMV: Cytomegalovirus, EBV: Epstein-Barr virus, HTLV-1: Human T-cell leukemia-lymphoma virus type 1, MCTD: Mixed connective tissue disease, SLE: Systemic lupus erythematosus, CNI: Calcineurin inhibitors, TMA: Thrombotic microangiopathy

The earlier clinical descriptions of “malignant” focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) were probably due to underlying CG.[6] However, the term “CG” was used for the first time to describe a new clinicopathologic entity, in patients with severe proteinuria and rapid progression to renal failure.[7] Soon after, patients infected with HIV were recognized to have similar pathological findings, an entity that has been termed HIV-associated nephropathy.[8] It was considered as a subtype of FSGS under the Columbia classification.[3] CG is now classified separately from FSGS under the spectrum of podocytopathies, as both have distinct pathogenetic mechanisms. Both CG and FSGS are characterized by podocyte injury, leading to podocyte dedifferentiation and proliferation in the former, and podocyte depletion in the latter.[5] Clinically, CG usually presents with massive proteinuria, hypertension, and renal insufficiency with rapid progression to ESRD. CG may occur concurrently with other glomerular diseases such as IgA nephropathy (IgAN),[9] membranous nephropathy, thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA),[10] systemic lupus erythematosus, and pauci-immune glomerulonephritis.[11]

DN is presumed in a patient with long-standing diabetes mellitus with proteinuria and renal dysfunction. Renal biopsy is required only in specific circumstances when an NDKD is suspected [Table 2].[112] Various forms of glomerular diseases may superimpose on DN.[12] Histologically, DN is characterized by excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix with mesangial expansion and glomerular basement membrane thickening.

| Short duration of diabetes (especially within 5 years of onset) |

| Absence of diabetic retinopathy/neuropathy |

| Atypical evolution |

| Rapid onset and progression of proteinuria |

| Massive proteinuria (>5-8 g/day) |

| Gross or persistent microscopic hematuria |

| Low serum complement levels |

| Nonproteinuric renal impairment |

| Unexplained rapid deterioration of renal function |

| Presence of systemic disorder affecting kidney |

The association of CG with DN has not been widely reported, which might be due to differences in biopsy policies in diabetic patients and also due to focal nature of CG, which could be missed on biopsy. The development of CG in DN has a unique pathology. Histologically, mesangial matrix expansion due to DN may prevent complete glomerular collapse, and it is accompanied by prominent glomerulosclerosis.[1]

On reviewing the literature, we have come across only one case series of superimposition of CG over DN. In a retrospective study by Salvatore et al., of 534 patients with biopsy-proven DN, 26 HIV-negative patients were found to have CG superimposed on DN (5% of total cases). More than 90% of patients had nephrotic-range proteinuria (mean 9.5 g/day) and mean serum creatinine was 3.8 mg/dl at the time of biopsy. Renal biopsy showed CG in 2%–30% (mean 16%) of glomeruli. DN classification was Class IV-12, III-8, IIb-4, and IIa-2. Extensive AH and moderate-to-severe AS were seen in most of the cases. Only one patient was treated with corticosteroids, while the rest were managed conservatively. Follow-up data were available in 17 patients, out of which 13 (77%) developed ESRD within 7 months of biopsy, while remaining four had increasing serum creatinine with stable proteinuria at 5–24 months’ follow-up.[1]

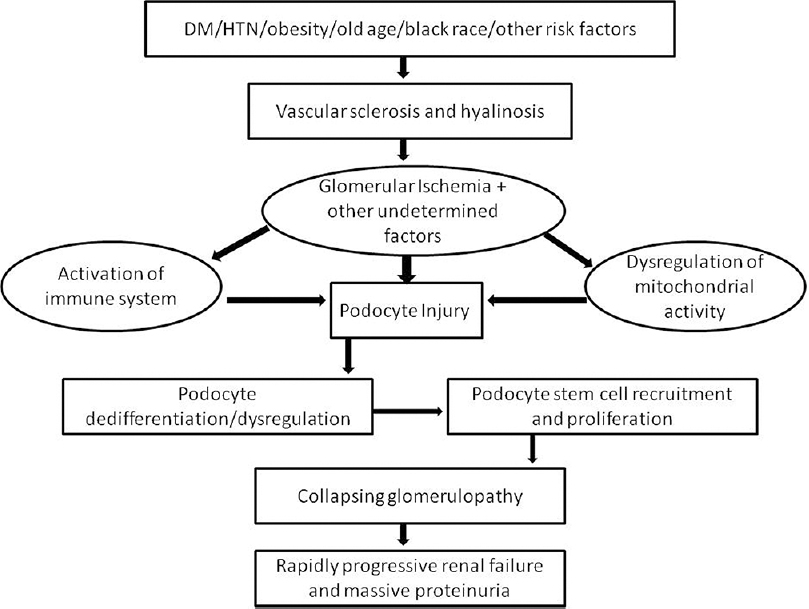

The pathogenesis of CG involves visceral epithelial cell injury leading to cell cycle dysregulation and a proliferative phenotype. Various authors proposed that renal ischemia may play a role in promoting glomerular collapse. The development of de novo CG in the transplant setting could be related to cyclosporine-induced arteriolopathy, hyalinosis, TMA, or acute rejection.[13] In a report on allograft nephrectomy specimens, zonal distribution of CG related to obliterative vascular changes was identified.[14] In another report, biopsies taken from renal allografts immediately adjacent to the areas of infarction demonstrated typical features of CG.[15] The ischemic hypothesis is substantiated by observations of CG in patients with TMA of native kidneys, cholesterol crystal embolism, and after renal artery stenosis.[10] A recent retrospective study reported 11 cases of CG associated with IgAN, and AS and TMA were identified in most of them.[9] The microvascular injury characterized by AS and AH, in patients with DN could lead to glomerular ischemia and podocyte injury, inducing collapsing glomerular lesions, similar to other forms of CG seen in native and transplant kidneys [Figure 2].[14]

- Proposed mechanism of development of collapsing glomerulopathy (CG) in diabetic nephropathy

The optimal treatment for CG is unknown. Primary or idiopathic forms are treated with various immunosuppressive agents with a poor response to therapy.[4] The development of CG irrespective of underlying disease is associated with a rapidly progressive course and poor prognosis.

In the present case, we have observed glomerular collapse in about 10% of nonsclerosed glomeruli, on the background of advanced DN with severe vascular disease (glomerular Class-IV, AH Score-2/2, AS Score-2/2). This is probably the first case report of CG superimposed on DN from India. The development of CG was attributed to vascular injury; hence, he was treated conservatively. However, the patient progressed to ESRD rapidly, requiring regular hemodialysis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Collapsing glomerulopathy superimposed on diabetic nephropathy: Insights into etiology of an under-recognized, severe pattern of glomerular injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:392-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:556-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: A working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:368-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- A proposed taxonomy for the podocytopathies: A reassessment of the primary nephritic diseases. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:529-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with rapid decline in renal function (“malignant FSGS”) Clin Nephrol. 1978;10:51-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nephrotic syndrome, progressive irreversible renal failure, and glomerular “collapse”: A new clinicopathologic entity? Am J Kidney Dis. 1986;7:20-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathology of HIV associated nephropathy: A detailed morphologic and comparative study. Kidney Int. 1989;35:1358-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis plays a major role in the progression of IgA nephropathy. II. Light microscopic and clinical studies. Kidney Int. 2011;79:643-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy is common in the setting of thrombotic microangiopathy of the native kidney. Kidney Int. 2016;90:1321-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Collapsing glomerulopathy in a case of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis. Indian J Nephrol. 2016;26:138-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nondiabetic kidney diseases in type 2 diabetic patients. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2013;32:115-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- De novo collapsing glomerulopathy in renal allografts. Transplantation. 1998;65:1192-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zonal distribution of glomerular collapse in renal allografts: Possible role of vascular changes. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:437-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glomerular collapse associated with subtotal renal infarction in kidney transplant recipients with multiple renal arteries. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:558-65.

- [Google Scholar]