Translate this page into:

Immune Complex Associated Glomerulonephritis in a Patient with Prefibrotic Primary Myelofibrosis: A Case Report

Address for correspondence: Dr. Tanya Sharma, Pathology and Lab Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. Department of Pathology and Lab Medicine, AIIMS Bhopal, Saket Nagar, Bhopal - 462 020, Madhya Pradesh, E-mail: tanya.patho@aiimsbhopal.edu.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A case of prefibrotic myelofibrosis with immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis is presented. A 45-year-old female, with history of right subclavian and axillary vein thrombosis, presented with abdominal distension, facial puffiness, and pedal edema. Evaluation revealed deranged renal functions with nephrotic range proteinuria and acute kidney injury. JAK2 mutation evaluated in view of portal vein thrombosis and splenomegaly was positive. Renal biopsy revealed mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with full house immune complex deposition on direct immunofluorescence (DIF). The patient had no signs or symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus and serological markers for autoimmune or collagen vascular disease were negative. Renal involvement in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) is uncommon and histological patterns of DIF negative mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis, and immunoglobulin A nephropathy have been reported.

Keywords

Glomerulopathy

immune complex mediated

mesangial proliferative

myeloproliferative neoplasms

prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis

Background

Myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders characterized by the proliferation of cells of one or more of the myeloid lineages. MPNs have a potential to progress to marrow failure due to myelofibrosis and ineffective hematopoiesis or transform to an acute blastic phase.

Primary myelofibrosis (PMF) is an MPN associated with JAK2 V617F, CALR, or MPL mutations and is characterized by bone marrow fibrosis and extramedullary hematopoiesis. The 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) revision of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia defines two stages of PMF: early/prefibrotic PMF (pre-PMF) and overt fibrotic PMF (overt PMF). Diagnostic criteria rely on bone marrow morphology and grade of fibrosis (0–1 in pre-PMF, 2–3 in overt PMF).[1].

Thrombotic and hemorrhagic events are frequently seen associated with MPNs especially essential thrombocythemia (ET), polycythemia vera (PV), and PMF. Prefibrotic PMF may have a different thrombotic risk profile than that of ET or overt (fibrotic) PMF.[23] Renal involvement is reported to be uncommon in cases of MPNs and even rarer in PMF. Renal involvement may be seen in form of thrombosis of renal arteries, extramedullary hematopoiesis, or leukemic infiltration in renal parenchyma causing obstructive uropathy and renal failure. The glomerular involvement in cases of MPNs has been described in various studies. Term “MPN-related glomerulopathy” has been proposed for the histomorphological changes, which include mesangial sclerosis and hypercellularity, segmental sclerosis, features of chronic thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), and intracapillary hematopoietic cell infiltration.[45] A case of nephrotic syndrome due to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis has been reported in patients of Pre-PMF.[6] However, none of the reported cases have shown immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis.

We report a case of nephrotic syndrome due to immune complex glomerulonephritis with crescents in a patient of pre-PMF.

Case Report

A 45-year-old female presented with complaints of abdominal distension and discomfort, fatigue, and malaise for past one and half years. She complained of pedal edema and facial puffiness for 3 months. There was no history of joint pain, rashes, photosensitivity, jaundice, cola colored urine, dry mouth, dry eyes, Reynaud's phenomenon, hematemesis, or black colored stools.

Her medical history was significant for right upper limb pain 3 years back, when she was diagnosed as right subclavian and axillary vein thrombosis, which was treated with anticoagulation for 6 months and had recovered. No formal workup for thrombotic state was done at that time. History was not significant for diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, or coronary artery disease. Patient did not give history of smoking or alcoholism. Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 150/100 mm Hg, pulse rate of 86/minute, regular with pedal edema 2+, moderate splenomegaly, and free fluid in abdomen.

Present investigations revealed anemia with hemoglobin of 10.4 gm/dl, total leukocyte count 6.88 × 109/L, platelet count 254 × 109/L, and a hematocrit of 27.1%. Red blood cells (RBCs) showed mild to moderate anisopoikilocytosis with presence of few microcytes and tear drop cells. No nucleated RBCs were noted in peripheral blood. Few large platelets and platelet anisokaryosis were seen. Mild left shift in white blood cell series was noted.

Urinalysis showed nephrotic range proteinuria with protein 3+, pus cells- 4–6/high power field, and RBCs 10–15/high power field. Further investigations revealed acute kidney injury (stage III, acute kidney injury network classification) with serum creatinine 3.04 mg/dl, serum albumin 3.0 gm/dl, and blood urea nitrogen 79.7 mg/dl. Twenty-four-hour urinary protein was 6.80 gm. Liver function tests were within normal limits. Ultrasonography of abdomen revealed splenomegaly of 22 cm, portal vein thrombosis, normal sized kidneys with raised echogenicity, and no active evidence of thrombosis of renal veins or inferior vena cava. Coagulation studies were within normal range. Protein C and Protein S levels were normal, ruling out factor deficiency-related thrombotic state. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels were raised to 692 U/L.

Serology for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, phospholipase A2 receptor (PLA2R), antinuclear antibody (ANA), antidouble stranded-DNA, antismith, antiphospholipid antibody, rheumatoid factor assay, anti Scl 70 (topoisomerase I), anti Ro, and anti La were negative. Complement levels C3 and C4 were within normal range. Hepatitis B surface antigen and antibodies for hepatitis C virus and human immunodeficiency virus were negative.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed high grade esophageal varices and stool for occult blood was positive. Cytogenetic analysis for JAK2 mutation was performed in view of portal vein thrombosis and splenomegaly, which turned out to be positive. Cytogenetics for BCR-ABL translocation was negative. Serum erythropoietin levels were 19 IU/L (Normal).

In view of positive JAK2 V617F mutation, a bone marrow examination was done. Bone marrow aspirate and trephine were hypercellular and showed expansion of granulopoiesis with megakaryocytic hyperplasia. Megakaryocytic atypia was seen along with areas of dense clustering of megakaryocytes. Frequent hypolobated forms as well as cloud-like nuclei were seen [Figure 1]. Erythroid series showed normoblastic maturation. Iron stores were 4+. Reticulin stain showed grade 0–I reticulin fibrosis, showing loose network of linear reticulin fibers with focal intersections [Figure 1]. In view of presence of splenomegaly and elevated serum LDH levels, the case was diagnosed as prefibrotic/early pre-PMF. A diagnosis of ET was excluded based on normal platelet counts and bone marrow morphology.

![(a) Hypercellular marrow showing expansion of granulopoiesis and increase in megakaryocytes. (b) Atypical megakaryocytes showing cloud-like, hypolobulated, and hyperchromatic nuclei, abnormally dislocated toward the trabecular bone. (c) Atypical megakaryocytes with cloud like nuclei in bone marrow aspirate. (d) Reticulin fibrosis grade 1 [H and E 40X]](/content/170/2021/31/1/img/IJN-31-50-g001.png)

- (a) Hypercellular marrow showing expansion of granulopoiesis and increase in megakaryocytes. (b) Atypical megakaryocytes showing cloud-like, hypolobulated, and hyperchromatic nuclei, abnormally dislocated toward the trabecular bone. (c) Atypical megakaryocytes with cloud like nuclei in bone marrow aspirate. (d) Reticulin fibrosis grade 1 [H and E 40X]

A renal biopsy was performed and samples for light microscopy and DIF were obtained. Light microscopy revealed 22 glomeruli. A total of 7 (31.8%) out of 22 glomeruli were globally sclerosed. Rest of the glomeruli showed diffuse mild to moderate mesangial hypercellularity and mesangial matrix expansion [Figure 2]. Six (27.2%) glomeruli showed segmental sclerosis. Fibrocellular crescents were seen in three (13.6%) glomeruli. No evidence of intracapillary thrombosis, tuft necrosis, or subendothelial deposits was seen. No evidence of hematopoietic cell infiltration was seen in interstitium. Tubular atrophy and interstitial inflammation was seen in 20–25% of renal cortex.

![Glomeruli showing expansion of mesangial matrix with mild increase in mesangial cellularity. Interstitial inflammation seen [Periodic Acid Schiff stain, 40X].](/content/170/2021/31/1/img/IJN-31-50-g002.png)

- Glomeruli showing expansion of mesangial matrix with mild increase in mesangial cellularity. Interstitial inflammation seen [Periodic Acid Schiff stain, 40X].

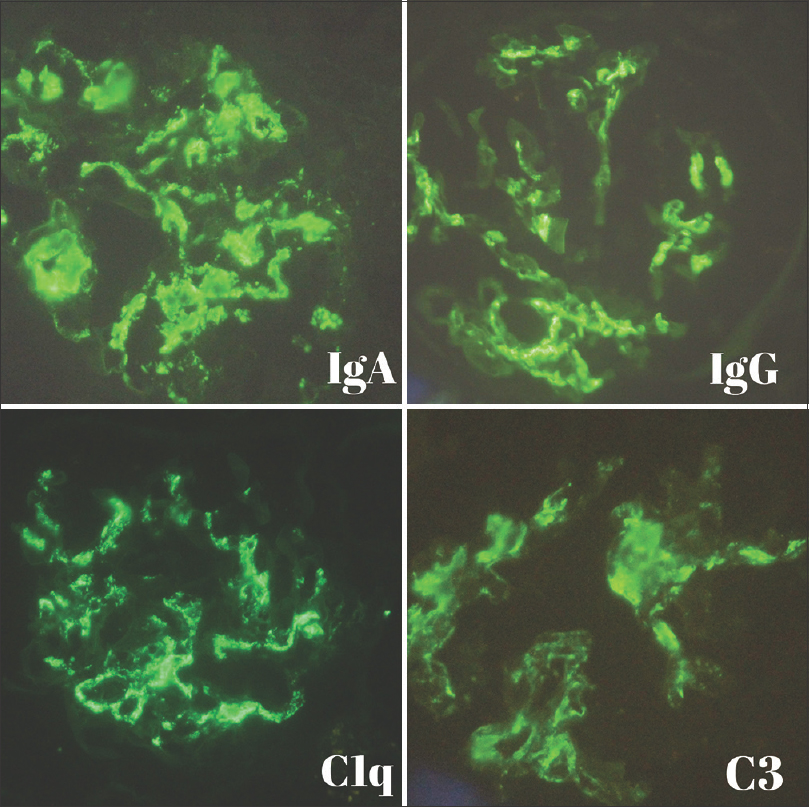

Sample for DIF contained seven glomeruli and revealed mesangial and glomerular capillary loops granular staining for immunoglobulin G (IgG) (2+), IgA (3+), immunoglobulin M (IgM) (2+), and complement components including C1q (2+) and C3 (3+) [Figure 3]. There was no light chain restriction and IgG subclass showed IgG1 and IgG3 positivity. The patient had no signs or symptoms of systemic lupus erythematosus and serological markers for autoimmune or collagen vascular disease were negative. A final diagnosis of mesangial proliferative glomerulonephritis with crescent was given.

- Direct immunofluorescence showing mesangial and peripheral capillary loops granular staining of IgA (3+), IgG (2+), C1q (2+), and C3 (3+)

Patient was started on oral steroids: Prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day and mycophenolate mofetil 1 gm twice daily in addition to telmisartan 80 mg once daily. After 1st month of follow-up her renal function improved (estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate 29 ml/min/1.73 m2 from 18 ml/min/1.73m2) and proteinuria decreased to 2.1 gm/day from 6.80 gm/day. She suffered recurrent episode of diarrhea and therefore mycophenolate was withdrawn, and steroids tapered. The patient is currently on follow-up and is in partial remission.

Discussion

According to the revised WHO classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia, the case was diagnosed as prefibrotic/early PMF as the case fulfilled the major and minor criteria.[7] Polycythemia was excluded based on hemoglobin less than a cut-off value of 16 gm/dl. ET and pre-PMF were close differential diagnosis in this case. However, platelet count less than the cut-off value of 450 × 109/L for ET, raised levels of LDH, and bone marrow morphology favored a diagnosis of pre-PMF. Also, the criteria for overt PMF were not met, as bone marrow did not show a reticulin fibrosis of more than MF 1 (Thiele et al.).[8].

Glomerular involvement in “Classical” MPN-related glomerulopathy include mesangioproliferative pattern with segmental sclerosis, chronic TMA, infiltrating hematopoietic cells in glomerular capillaries with absence of crescents.[5] It is usually pauci immune on DIF. However, in the present case, there were no features of chronic thrombotic microangiopathy or intracapillary hematopoietic cell infiltrate. Instead, DIF showed a full house pattern. Negative serological evaluation and lack of clinical features favored nonlupus full house nephropathy.

IgA nephropathy has been reported previously in cases of PV and ET.[910] IgA being the dominant immunoglobulin on DIF in the present case, a possible diagnosis of IgA nephropathy was considered. However, IgA nephropathy was precluded based on significant C1q deposition, which is uncommon in IgA nephropathy. However, electron microscopy could not be performed due to unavailability.

It has been postulated that autoimmunity, immune dysfunctions, and chronic inflammation are important factors in pathogenesis of MPNs, including PMF. Patients of MF have shown circulating immune complexes in blood, indicating role of immune derangements in pathogenesis of MF.[111213] It is suggested that these immune complexes form in circulation and get trapped in bone marrow or may form in bone marrow itself and activate the complement system.[1415].

In similar lines, we hypothesize that kidney disease in our patient might have developed due to entrapment of circulating immune complexes in glomeruli, formed in circulation at an early stage of pre-PMF, accompanied by activation of complement system as evidenced by deposition of complement components C3 and C1q.[16] Also, chronic portal vein thrombosis may result in functional bypass of hepatic reticuloendothelial system due to portosystemic shunting and consequently reduced hepatic clearance of immune complexes. This could have contributed to pathogenesis in the present case. Full house positive membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in patients with portosystemic shunt has been reported previously.[17].

The present case, to the best of our knowledge, is the first reported case of nonlupus full house immune complex-associated glomerulonephritis in a patient of pre-PMF. It is an addition to the existing list of glomerular diseases in hematological malignancies. We conclude that renal involvement and glomerular diseases have a wide spectrum and can occur early as well as late in the course of MPNs and immune complex-associated glomerulonephritis could be a manifestation of early occurrence of renal disease in this continuum.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Diagnosis and management of prefibrotic myelofibrosis. Expert Rev Haematol. 2018;7:537-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- The underappreciated risk of thrombosis and bleeding in patients with myelofibrosis: A review. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:1595-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Idiopathic myelofibrosis with extramedullary haematopoiesis in the kidneys. Clin Nephrol. 1999;52:256-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in a patient with prefibrotic primary myelofibrosis. BMJ Case Rep 2018 doi: 10.1136/bcr2017-223803

- [Google Scholar]

- The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2391-405.

- [Google Scholar]

- Essential thrombocythemia vs.pre-fibrotic/early primary myelofibrosis: discrimination by laboratory and clinical data. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7:643-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal biopsy cases in myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN) CEN Case Rep. 2013;2:215-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- IgA nephropathy in a patient with polycythemia vera.Clinical manifestation of chronic renal failure and heavy proteinuria. Am J Nephrol. 2002;22:397-401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immune derangements in patients with myelofibrosis: The role of Treg, Th17, and sIL2Rα. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116723.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immune complexes in myelofibrosis: A possible guide to management. Br J Haematol. 1978;39:233-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Idiopathic myelofibrosis: A possible role for immune-complexes in the pathogenesis of bone marrow fibrosis. Br J Haematol. 1981;49:17-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Immunologic abnormalities in myelofibrosis with activation of the complement system. Blood. 1981;58:904-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Full house” positive immunohistochemical membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in a patient with portosystemic shunt. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:2258-62.

- [Google Scholar]