Translate this page into:

Membranous Nephropathy with Collapse: Poor Prognosis

Address for correspondence: Dr. Raja Ramachandran, Department of Nephrology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh - 160 012, India. E-mail: drraja_1980@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Sir,

Collapsing glomerulopathy (CG), initially reported in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, is now described with other etiologies such as autoimmune diseases, malignancies, drugs, and apolipoprotein 1 (APOL1) risk variants.[1] Primary membranous nephropathy (MN), an autoimmune glomerular disease, is not commonly described with CG, barring isolated reports.[23]

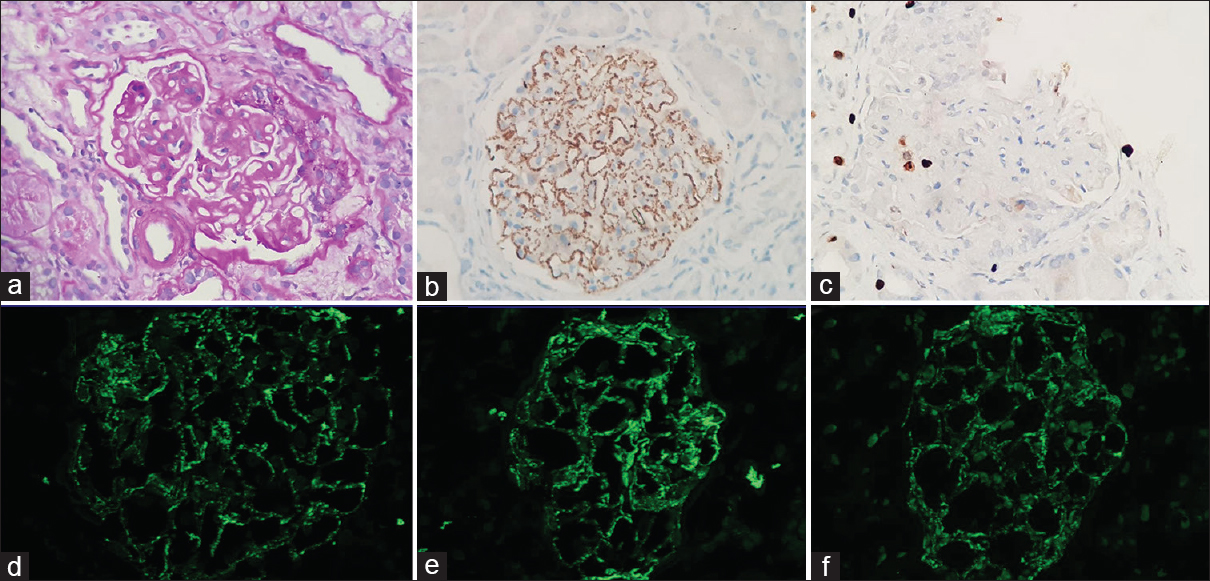

We report the clinical outcome of five patients with coexistent primary MN and CG from our center after informed consent from the patients. All the patients were worked up for secondary etiologies for MN including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, malignancy, and exposure to drugs associated with MN. MN and CG were diagnosed based on typical features of light microscopy, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. Serum anti-PLA2R antibodies (EUROIMMUN AG, Lubeck, Germany) and tissue PLA2R stain were done in all patients. Loss of Wilms' tumor-1 and gain of Ki67 confirmed dedifferentiation of podocytes causing glomerular collapse. Nephrotic syndrome was defined as proteinuria ≥3.5 g/day along with hypoalbuminemia and oedema.[4] Complete remission (CR) and partial remission (PR) were defined according to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome criteria.[4] Of the total 321 patients enrolled in the MN registry at our center, 5 (1.45%) adult patients with coexistent primary MN and CG were identified. The median age of patients was 29.50 [interquartile range (IQR): 25–33.75] years, and all were males. The median (IQR) serum creatinine, serum albumin, and 24-hour proteinuria at presentation were 1.8 (0.9–2.4) mg/dL, 2.2 (1.8–3.7) g/dL, and 6.2 (3.8–9.7) g/day, respectively. Four (80%) of the five patients presented with nephrotic syndrome; three (60%) had renal dysfunction and 2 (40%) had hypertension at diagnosis. Serum anti-PLA2R antibody was positive in two (40%) patients (Patients 1 and 5). None of the patients had evidence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV infection, lupus nephritis, malignancy, or potential drug exposure. The clinical characteristics of each patient are shown in Table 1. Renal biopsy findings are shown in Figure 1a–f. PLA2R stain was positive along the glomerular capillary wall in three (60%) patients [Figure 1b]. Significant interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy (>25% of the cortical area) and glomerulosclerosis were noted in two (40%) patients (Patients 1 and 4, on repeat biopsies in both). All patients received cyclical cyclophosphamide and steroid therapy along with angiotensin receptor blockade and a statin. At 6 months of therapy, PR was observed in one (20%) patient, CR in one (20%) patient, and no response in three (60%) patients. Both the patients (Patients 1 and 2) in remission were PLA2R-related MN and had negative anti-PLA2R at 6 months (anti-PLA2R <14 RU/mL); Patient 1 had anti-PLA2R antibody titer of 57.9 RU/mL at baseline and Patient 2 had negative serum anti-PLAR antibody throughout. At 12 months of therapy, one (20%) patient was in CR, one (20%) had PR, and three (60%) were non responders. Patient 1 had a relapse of the disease at 50 months of follow-up with an increase in anti-PLA2R to 286 RU/mL. Patients 1 and 5 were treated with rituximab (two doses of 1 g each 2 weeks apart) for relapse and resistant disease, respectively. Although serum creatinine normalized in one (Patient 5), both patients showed no response in proteinuria after rituximab therapy. Anti-PLA2R at the end of 6 months of rituximab was 180 RU/mL (Patient 1) and 194 RU/mL (Patient 5). At the last follow-up (median: 36 months), only one (20%) patient was in remission (CR), and four (80%) patients had a resistant disease with two (40%) of them receiving renal replacement therapy.

| Patient no. | Follow-up (months) | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) Baseline | Serum albumin (g/dL) Baseline | Proteinuria (g/day) Baseline | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) 6 m | Serum albumin (g/dL) 6 m | Proteinuria (g/day) 6 m | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) 12 m | Serum albumin (g/dL) 12 m | Proteinuria (g/day) 12 m | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) LV# | Serum albumin (g/dL) LV | Proteinuria (g/day) LV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 56 | 1.8 | 3.12 | 6.2 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 8.3 |

| Patient 2 | 24 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 0.12 | 0.8 | 4.2 | 0.34 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 0.25 |

| Patient 3 | 7 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 7.8 | 3.8 | 3.4 | - | - | - | 7.8 | 3.8 | 3.4 |

| Patient 4* | 132 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 9 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 7.2 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 8 | 12.2 | 2.9 | 5.1 |

| Patient 5 | 36 | 0.83 | 1.8 | 10.5 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 14 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 23 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 10.7 |

*Underwent renal transplant (serum creatinine and proteinuria at 24 months of renal transplant are 1 mg/dL and 321 mg/day, respectively); #LV: last visit (prior to renal transplant in patient 4)

- (a) PAS-stained paraffin section showing membranous nephropathy with overlying podocyte hyperplasia indicating collapse, (b) PLA2R immunostain showing fine granular positivity along the capillary wall, (c) Ki67 immunostain showing occasional positivity on the podocytes, and (d-f) direct immunofluorescence showing fine granular capillary wall positivity from IgG, kappa, and lambda, respectively (400× magnification)

Al-Shamari et al.[2] described three HIV-negative patients with coexistent CG and MN who progressed to advanced chronic kidney disease despite immunosuppressive therapy. Although well known to be associated with autoimmune diseases,[1] primary MN is not commonly described with CG and the pathogenesis is uncertain. A possibility of viral infection causing both podocyte injury (CG) and increased expression of viral antigens on the podocyte foot process leading to immune complex deposition (MN) was also put forward.[2] To conclude, we observed 80% of patients to be resistant to therapy among five non-HIV-infected patients with coexistent MN and CG. The association of CG in patients with primary MN may act as a poor prognostic factor for response to standard therapy. Larger prospective multicentric studies shall provide a better understanding of this association.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Collapsing glomerulopathy coexisting with membranous glomerulonephritis in native kidney biopsies: A report of 3 HIV-negative patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:591-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histopathologic effect of APOL1 risk alleles in PLA2R-associated membranous glomerulopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64:161-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int (Suppl 2):181-5.

- [Google Scholar]