Translate this page into:

Rapidly progressive renal failure due to chronic lymphocytic leukemia - Response to chlorambucil

Address for correspondence: Dr. Naushad Ali Junglee, 3rd Floor, Hebog Day Room, Ysbyty Gwynedd, Penrhosgarnedd, Bangor, LL57 2PW, Wales, UK. E-mail: naushadaj@yahoo.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia tends to follow an indolent course and despite infiltration of leukemic cells in numerous organs, resultant target organ damage is uncommon. We present a case of an 83-year-old Caucasian lady who presented with rapidly worsening renal impairment over a several month period with a serum creatinine peak of 2.82 mg/dl. Despite numerous investigations an immediate cause was not apparent. A renal biopsy was therefore conducted which revealed dense infiltration of the interstitium with small lymphocytic lymphoma. Given her age and frailty she was treated with single alkylating agent chemotherapy (chlorambucil). This resulted in a marked decrease in lymphocyte count and resolution of renal impairment close to her previous baseline level. To our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature to demonstrate a marked resolution in renal impairment with chlorambucil alone. We also highlight the value of renal biopsy in identifying a rare cause of renal impairment.

Keywords

Chlorambucil

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

renal biopsy

renal failure

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a chronic lymphoproliferative disorder recognized by a mass production of monoclonal incompetent lymphocytes.[1] In most cases it follows an indolent and prolonged clinical course. Infiltration with B-CLL cells may occur in any organ, mostly lymphoid tissues, such as the spleen, liver, and peripheral lymph nodes. Renal infiltration has been described in 63–90% of all CLL patients who underwent post-mortem autopsy.[2–4]

The major complications of CLL arise from cytopenias (anemia, thrombocytopenia) and immune dysfunction. Infections are responsible for approximately 50% of all deaths.[5] Renal failure caused by direct organ infiltration is very uncommon.[36] We present a case of a 83-year-old female with stable CLL of 6 years until she presented with rapidly progressive renal impairment due to leukemic infiltration. She was treated with single-agent chemotherapy (chlorambucil) and had a gratifying response with significant improvement in her renal function.

Case Report

An 83-year-old Caucasian lady referred to the nephrology clinic in January 2011 with rapidly worsening renal impairment. Her serum creatinine had risen from the baseline value of 1.40 mg/dl to 2.82 mg/dl over a period of around 7 months [June 2010 to January 2011; Figure 1]. Her past medical history included breast carcinoma treated with right-sided mastectomy and axillary clearance 15 years previously, low-rectal carcinoma treated with chemo- and radiotherapy 6 years previously and CLL. The latter had been diagnosed 6 years previously when a full blood count demonstrated a lymphocytosis of 14 × 109/l, the lymphocytes having the typical morphology and expressing the surface markers CD19, CD5, CD23 with weak surface immunoglobulin and no FMC7 (CLL score 5/5).[7] The blood count had been otherwise normal, and she had no lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. The CLL was therefore classed as A(0) and no treatment had been recommended. Her renal function was normal at this stage.

At presentation with renal failure her main complaint was a 1-month history of fatigue that worsened on exertion. She had not developed night sweats or lost weight. Her regular medications included amlodipine 5 mg od PO and ranitidine 150 mg od PO. She denied the use of any over-the-counter medications or supplements. There were no recorded allergies. She lived alone but continued to manage with all her activities of daily living despite her fatigue. She was a nonsmoker and teetotaler.

- Graph illustrating trends in serum creatinine between June 2010 and May 2011. Presentation to the nephrology clinic was in January 2011

Clinical examination revealed a comfortable lady at rest with all vital observations within normal limits. There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy or conjunctival pallor. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and abdominal examinations were unrevealing and in particular there was no evidence of organomegaly or recurrence for the aforementioned solid tumor malignancies.

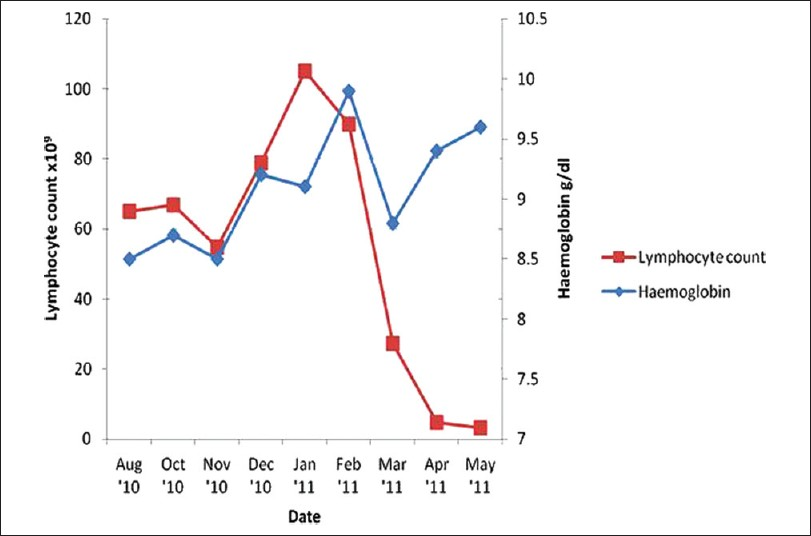

Her hemoglobin was measured at 7.7 g/dl, white cell count 107.8 × 109/l, lymphocytes 101.3 × 109/l, and platelets 200 × 109/l [Figure 2]. The blood film again showed the typical features of untransformed CLL. There was no evidence of hemolysis (no spherocytes, reticulocytes 1.3%, direct Coombs’ test negative, and bilirubin 0.23 mg/dl). Her renal function was severely compromised (urea 41.7 mg/dl and creatinine 2.82 mg/dl) having shown a rapid deterioration over the preceding 8 months [Figure 1]. The peak of her creatinine rise coincided with the peak lymphocyte count in January 2011 [Figure 2].

- Graph illustrating trends in hemoglobin and lymphocyte count between August 2010 and May 2011. Presentation to the nephrology clinic was in January 2011. Treatment of CLL with chlorambucil was commenced in February 2011

Dipstick urinalysis demonstrated protein+and a protein: Creatinine was 44 mg/mmol. Urine culture was negative for growth. Serum and urine electrophoresis were normal. A vasculitic screen (including ANA, ANCA, and dsDNA) was negative. CRP was also normal. Ultrasound of the renal tract was normal with both kidneys measuring 10.9 cm. There was no evidence of postrenal obstruction or intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy.

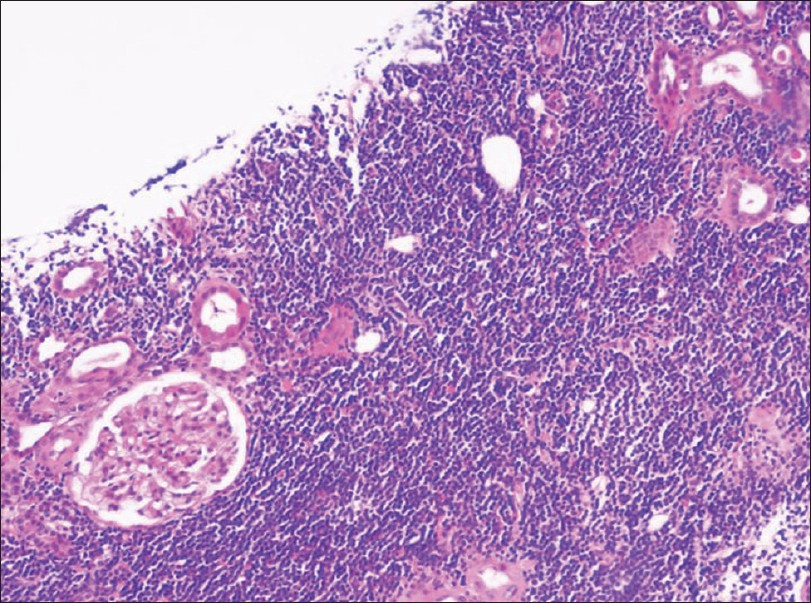

Given the lack of an obvious cause for this lady's renal impairment, a renal biopsy was performed following transfusion two units of packed red cells, local anesthetic and real-time ultrasound imaging guidance. Samples were successfully obtained without complication. Light microscopy of a core revealed dense infiltration of the interstitium with small lymphocytic lymphoma [Figure 3]. Some of the glomeruli were globally sclerosed consistent with chronic kidney disease; however the remaining glomerular and tubular architecture remained preserved [Figure 3]. Immunofluorescence studies were negative for immune complex deposition.

- Renal biopsy demonstrating confluent B-CLL infiltration of the interstitum within which there are few glomeruli and tubules with preserved architecture (H and E; ×40 magnification)

Based upon these findings therapy for CLL was recommended. She was considered too frail for combination chemotherapy with monoclonal antibodies and was therefore given single alkylating agent therapy with chlorambucil 10 mg daily for 14 days repeated every 4 weeks. This was very well-tolerated apart from the need for two unit red cell transfusions and a short treatment delay for asymptomatic mild thrombocytopenia. Her renal function began to improve immediately after starting the first cycle of treatment. By the third, her lymphocytosis had resolved and her serum creatinine had fallen to 1.42 mg/dl [Figures 1 and 2]. She remained clinically stable but with persistent fatigue.

Discussion

Some degree of renal infiltration in CLL is common but the incidence of marked infiltration such as that seen in our patient is probably much less.[8] Schwartz et al. study reported on 47 patients with CLL evaluated at autopsy.[2] They found leukemic involvement in 90% of patients, but noted that renal infiltration occurred in only four cases in a more diffuse, although still well-defined, manner.

Renal failure due to leukemic infiltration in CLL is rare. Although such infiltration is well recognized in acute leukemia, only 14 cases of renal failure due to CLL cell infiltration (including ours) have been described in the literature so far.[9] Renal failure in the context of CLL is usually secondary to complications of disease and/or its treatment (e.g., infection or tumor lysis syndrome following chemotherapy). In a recent study of 700 patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and CLL, 17 CLL patients proposed to have manifestations of renal failure of which only three of them were directly related with CLL.[10] Several case reports have described patients with only mild CLL disease activity (as in our patient) although more aggressive forms can also exist along with renal failure.[11–17] Despite thorough initial investigation, a straightforward cause for our patient's renal impairment was not apparent. Thus, a renal biopsy was required for diagnosis. In retrospect, renal ultrasound imaging revealed normal sized kidneys on a background of chronic kidney disease – possibly suggestive of relative organomegaly due to lymphocyte cell infiltration.[10–12] However, the kidney size can also be within normal limits.[13–15]

Renal histology may demonstrate various lesions known to be associated with CLL, including immunotactoid glomerulopathy, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type 1 (with or without mixed cryoglobulinemia), urate nephropathy, amyloidosis, and minimal change disease.[1316] The biopsy of our patient did not exhibit any features of the latter and clinically there were no signs to support the nephrotic syndrome. However, our patient did have mild proteinuria which is associated with CLL infiltration. Interstitial infiltrates are a common occurrence in CLL, but more diffuse ones as demonstrated in our case may result in target organ damage. The mechanism by which CLL cells cause renal dysfunction is not known, but it has been postulated that tumor infiltration causes compression of the tubular lumen and microvasculature, producing intrarenal obstruction and ischemia respectively. Interestingly, our biopsy did not reveal features of tubular compression [Figure 3].

Given concerns regarding age and potential intolerance of intensive chemotherapy, a decision was made to give chlorambucil only. Previous reports in this setting have initiated more aggressive treatment regimes including fludarabine/rituximab/prednisone, methyprednisolone/cyclophosphamide, and adjunctive radiotherapy. Response to treatment has varied from complete resolution of the acute renal failure to more often a partial response to no response.[10131418] To our knowledge, there has only been one previous case in the literature where chlorambucil has been used solely and this did not result in a return to baseline renal function.[13] Thus, our case report is the first case to date to demonstrate a marked resolution in renal impairment with chlorambucil alone.

In conclusion, we present successful treatment of rapidly progressive renal failure due to leukemic infiltration in an elderly Caucasian female with CLL. Despite leukemic infiltration being common in CLL, detailed evaluation is recommended for patients with increased serum creatinine levels and no other apparent cause for deterioration. In particular, our case highlights the value of renal biopsy to confirm diagnosis. When diagnosed, the condition tends to respond well to a variety of chemotherapeutic agents and may avert the need for renal replacement therapy. Our case is the first to date to demonstrate a marked resolution in renal impairment with chlorambucil alone. This treatment could be considered as an alternative to more intensive regimes where side effect profiles could be detrimental to the patient given age, frailty, and other comorbidities.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- New insights into the pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010;20:377-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of leukemic infiltrates in various organs in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Human Pathol. 1981;12:432-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- An autopsy study of 1206 acute and chronic leukemias (1958 to 1982) Cancer. 1987;60:827-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal involvement in myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative disorders: A study of autopsy cases. Gen Diagn Pathol. 1997;142:147-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Infection and immunity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1039-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- The immunological profile of B-cell disorders and proposal of a scoring system for the diagnosis of CLL. Leukemia. 1994;8:1640-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure secondary to chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A case report. Medscape J Med. 2008;10:67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal infiltrate by a plasmocytoïd chronic B lymphocytic leukaemia and renal failure: A rare occurrence in nephropathology.A case report and review of the literature. Nephrol Ther. 2011;7:479-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney involvement and renal manifestations in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and lymphocytic leukemia: A retrospective study in 700 patients. Eur J Haematol. 2001;67:158-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible renal failure due to renal infiltration and associated tubulointerstitial disease in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1990;5:616-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:770-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible renal failure due to specific infiltration of the kidney in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1550-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute renal failure due to leukaemic infiltration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Case report. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2005;59:53-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal failure caused by leukaemic infiltration in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:1131-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reversible renal failure due to specific infiltration on chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Am J Med. 1988;85:579-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal failure due to leukaemic infiltration in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1990;5:1051-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal dysfunction due to leukemic infiltration of kidneys in a case of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hemodial Int. 2010;14:87-90.

- [Google Scholar]