Translate this page into:

Reduced Baroreflex Sensitivity, Decreased Heart Rate Variability with Increased Arterial Stiffness in Predialysis

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

High cardiovascular morbidity and mortality is observed in predialytic chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. The underlying mechanism of cardiovascular dysfunction often remains unclear. The present study was designed to perform multiparametric assessment of baroreflex sensitivity (BRS), arterial stiffness indices, and cardiovascular variabilities (heart rate variability [HRV] and blood pressure variability [BPV]) together in predialytic CKD patients; compare it with normal healthy controls; and determine their relationships in predialytic nondiabetic CKD patients. Thirty CKD Stage 4 and 5 predialytic non-diabetic patients and 30 healthy controls were enrolled in the study. BRS was determined by spontaneous sequence method. Short-term HRV and BPV were assessed using 5 min beat-to-beat data of RR intervals and blood pressure by time domain and frequency domain analysis. Arterial stiffness indices - carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV) and augmentation index - were measured using SphygmoCor Vx device (AtCor Medical, Australia). Predialytic CKD patients had significantly low BRS, high PWV, and low HRV as compared to healthy controls. Independent predictors of reduced systolic BRS in predialytic CKD patient group on multiple regression analysis emerged to be increase in calcium-phosphate product, increase in BPV, and decrease in HRV. Predialytic nondiabetic CKD Stage 4 and 5 patients have poor hemodynamic profile (higher PWV, lower HRV, and reduced BRS) than healthy controls. Reduced HRV and altered calcium-phosphate homeostasis emerged to be significant independent predictors of reduced BRS.

Keywords

Baroreflex sensitivity

blood pressure variability

chronic kidney disease

heart rate variability

predialysis

pulse wave velocity

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. Surprisingly, even mild impairment of renal function is associated with high cardiovascular mortality,[1] and this relation of CVD with renal impairment has also been clearly demonstrated in predialytic patients.[2]

Recent studies have speculated that one of the principal mechanisms responsible for the underlying cardiovascular dysfunction is probably linked to alteration in baroreflex functioning, which could either be attributed to the accelerated central arterial stiffness and/or the autonomic dysfunction in CKD.[3]

Few studies have focused on the association of baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) and arterial stiffness in predialytic CKD patients[4] and on patients undergoing hemodialysis[5] with conflicting results, while the association of BRS and cardiovascular variabilities has been dealt scarcely only in patients undergoing hemodialysis.[6] Exhaustive evaluation of BRS together with arterial stiffness and cardiovascular variabilities has been done only in two studies in patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis[7] and renal transplant.[8] Correction of the renal deterioration in patients already on renal replacement therapy could probably obscure the relationship between these parameters. Moreover, patients on renal replacement therapy have additional influences attributable to effects of dialysis membrane,[9] dialysate calcium level,[10] fluid status,[11] and immunosuppressive regimen[12] in transplant recipients. All these factors could potentially affect BRS, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular variabilities. Thus, it becomes important to investigate the status of all these parameters together and understand their interrelationship in predialytic patients.

To the best of our knowledge, no study till date has performed a comprehensive evaluation of BRS, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular variabilities (heart rate variability [HRV] and blood pressure variability [BPV]) simultaneously in predialytic patients. Thus, the objective of the present study was to make a combined assessment of these parameters together in predialytic CKD patients; compare it with normal healthy controls; and determine their interrelationships by correlation analysis.

Methods

Patient population and study design

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Human Subjects, AIIMS, New Delhi, with the Institutional Review Board approval. CKD Stage 4 and 5 patients not on dialysis along with age- and gender-matched healthy controls were recruited from the Department of Nephrology, AIIMS, and the cardiovascular parameters were evaluated in the Autonomic and Vascular Function Testing Laboratory, Department of Physiology, AIIMS. Patients with acute illness, active arrhythmias, or neurological abnormality before onset of CKD were excluded from the study in addition to those with diabetes considering its possible direct impact on autonomic and vascular functions. Healthy controls included subjects who were due for voluntary kidney donation under the renal transplantation program at the institute and were fully worked up and declared fit for donation. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants of the study.

Measurements were carried out on the same day with prior standard instructions given to participants that included report to laboratory either in fasting state or 3–4 h after a light meal, refrain from coffee, tea or smoking 24 h before test, and avoid alcohol 48 h before the test. Tests were performed after 10 min of supine rest in a temperature controlled (22–25°C) room.

Assessment of baroreflex sensitivity, heart rate variability, and blood pressure variability

Continuous beat–to-beat blood pressure (BP) and lead II electrocardiogram (ECG) were recorded noninvasively for 5 min in patients by Finometer® (Finometer® model 2, Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Measures of BRS, HRV, and BPV were extracted using Nevrokard Software (Nevrokard, Izola, Slovenia). Spontaneous BRS was quantified using time domain sequence method with regression analysis of the relationship between BP and RR intervals.[13] HRV was assessed using time and frequency domain analysis, while time domain parameters of BPV were used for analysis. The details of the methodology have been mentioned in our previous papers.[8]

Assessment of vascular function

Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV) was determined using the SphygmoCor device (AtCor Medical, Australia). PWV was derived by applying a previously described and validated methodology that uses an ECG-gated signal and anthropometric distances.[814]

Central pulse wave profile was obtained by radial artery tonometery using the SphygmoCor Vx pulse wave analysis system (AtCor Medical). Central pulse wave profile was estimated using the validated generalized transfer function algorithm to determine the central systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP), augmentation pressure, and heart rate-adjusted augmentation index (AI).[815]

Biochemical assays

Morning fasting blood samples were taken and analyzed in local biochemistry and specialty renal laboratory using enzymatic methods in standard autoanalyzers.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for parametric data and median (quartile range) if data were nonparametric. Parametric data were analyzed using a two-tailed independent t-test, while analysis of nonparametric data was done using a two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlation was done using two-tailed Spearman's correlation analysis with univariate linear regression. All statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla California USA). Multiple regression analysis for BRS was done using backward method including all variables found to have P < 0.07 in univariate correlation analysis using MedCalc software version 12.2.1.0 (Ostend, Belgium) for Windows.

Results

Comparison of parameters of chronic kidney disease patients and controls

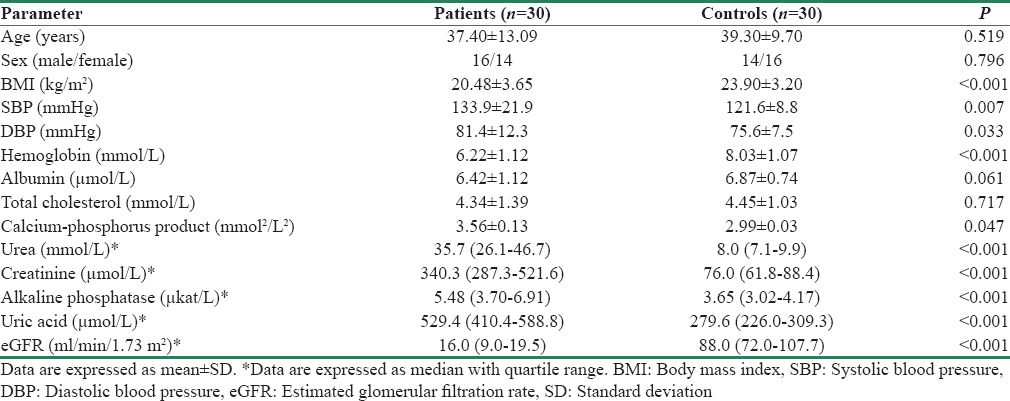

Thirty CKD Stage 4 and 5 predialytic nondiabetic patients and 30 healthy controls were enrolled in the study. There were equal numbers of smokers in both groups (2 in each group). The demographic and clinical profiles of the patient and control group are shown in Table 1.

As expected, the CKD patients had lower body mass index (BMI) and hemoglobin as compared to control group because of malnutrition related to chronic disease. On similar lines, CKD patients had a significantly higher SBP, DBP, and calcium-phosphorus product. However, there was no significant difference found in serum cholesterol and albumin levels between the two groups. CKD patients as anticipated had higher blood urea, serum creatinine, alkaline phosphatase, and uric acid and a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) than the control group.

Among the CKD group, 80% were hypertensives with most patients requiring either one or two drugs for antihypertensive therapy. Most common etiology was found to be chronic glomerulonephritis and chronic interstitial nephritis. Two-thirds of patients were in CKD Stage 4 and one-third were in Stage 5, and all of them were on conservative management and not yet started on dialysis.

Baroreflex sensitivity of patient and control groups

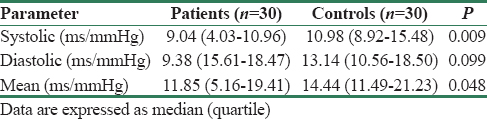

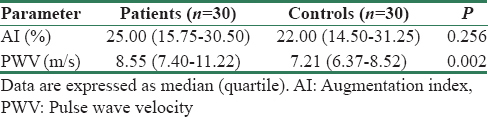

Systolic and mean BRS were significantly lower in patients in comparison to healthy controls [Table 2 and Figure 1]. Although the difference in diastolic BRS was not significant, a trend toward decreased BRS was seen in patients.

- Systolic baroreflex sensitivity of patients and controls. Figure shows markedly lower systolic baroreflex sensitivity in patients than controls. *indicates P < 0.001

Arterial stiffness parameters of patient and control groups

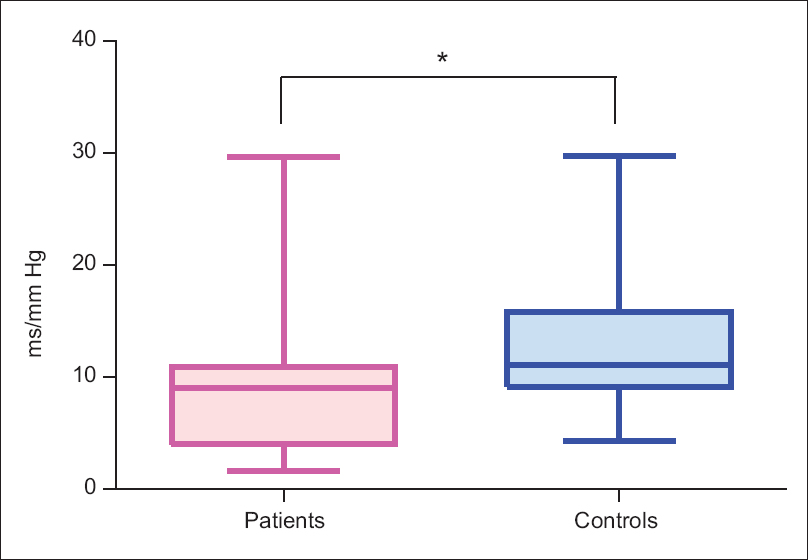

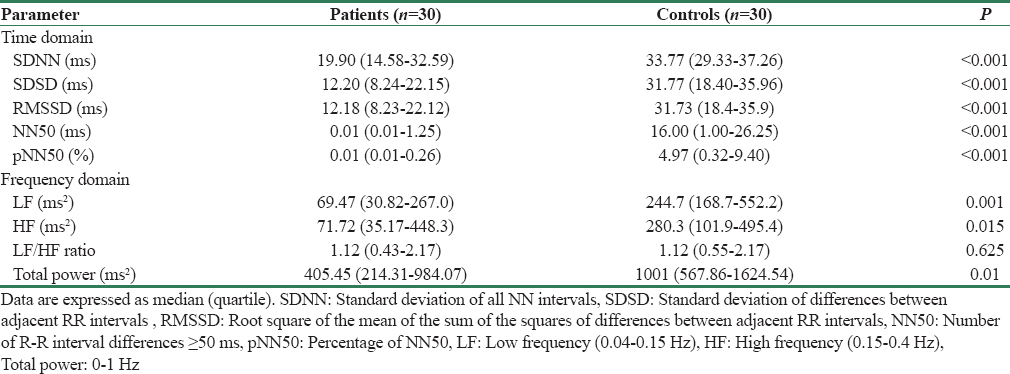

Interestingly, PWV of patients was significantly high as compared to controls [Figure 2] while there was no significant difference found between the two groups in AI [Table 3].

- Pulse wave velocity of patients and controls. Figure shows significantly higher pulse wave velocity in patients than controls. *indicates P < 0.001

Heart rate variability parameters of patient and control groups

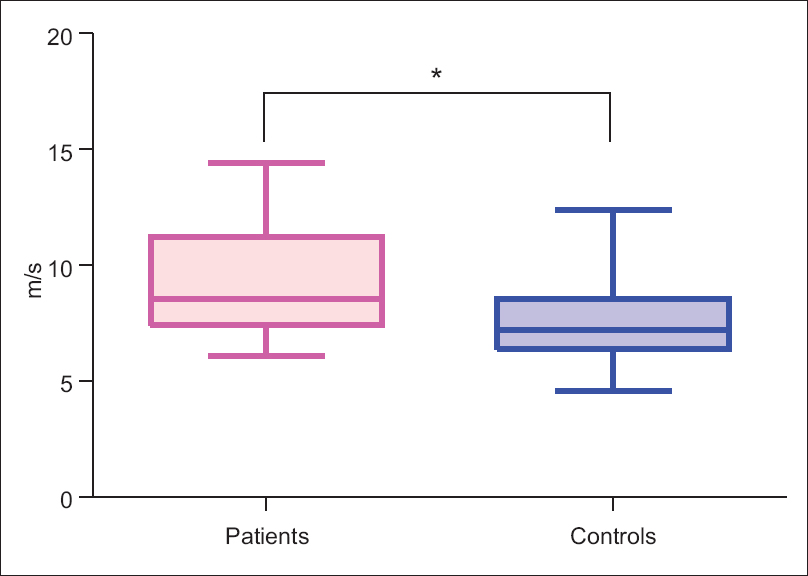

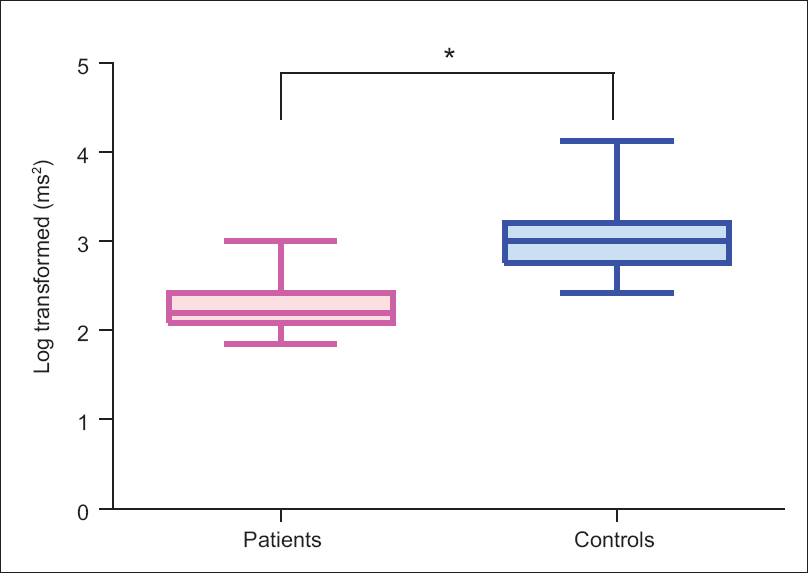

All the parameters of time domain analysis were significantly depressed in CKD patients as compared to healthy controls [Table 4]. While in the frequency domain analysis - low frequency (LF), high frequency (HF), and total power (TP) of HRV [Figure 3] were found to be significantly depressed in patients compared to controls, which is in line with the time domain results. The LF/HF ratio was not statistically different between the two groups due to the reduction in both sympathetic and parasympathetic modulations in the patient group.

- Heart rate variability (frequency domain-total power) in patients and controls. Figure shows significantly higher heart rate variability in patients than controls. *indicates P < 0.05

Blood pressure variability parameters of patient and control groups

Time domain parameters of BPV were not statistically different between patients and controls.

Association of glomerular filtration rate with vascular and autonomic parameters

Interestingly, we found that GFR was correlated to both vascular (PWV - r = −0.3430; P = 0.0073) and autonomic (HRV measure number of RR interval differences ≥50 ms [NN50] - r = 0.5505; P < 0.0001 and systolic BRS - r = 0.3179; P = 0.0133) parameters when analysis was done using the pooled data of both patients and controls. This portrays the possible relationship between kidney functions and the observed spectrum of vascular and autonomic functions varying across the two distinct study groups. The same relationship was lost when correlation analysis was limited to the data obtained from patient group alone.

Determinants of baroreflex sensitivity

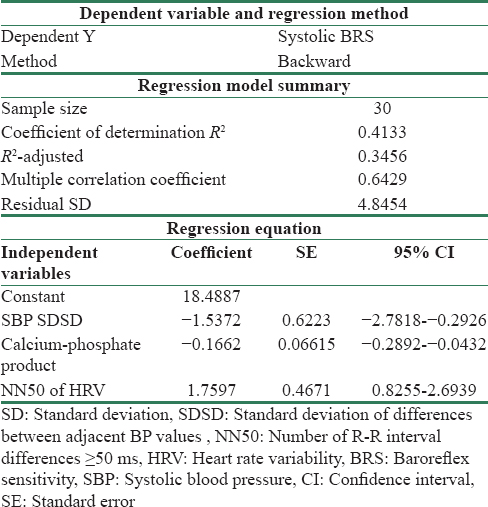

Univariate correlation was performed to decipher the association of systolic BRS with demographic, biochemical, clinical, vascular, and autonomic parameters with both patients and controls together and patients group alone and thus determine the plausible pathophysiological factors associated with the reduction in BRS. With the pooled data of patients and controls, BRS was found to correlated with numerous parameters - age, BMI, and smoking status (known demographic parameters), biochemical parameters related to kidney function (serum creatinine, eGFR, calcium-phosphate product, and urea), pulse pressure variability and HRV (NN50, standard deviation of all NN intervals [SDNN], root square of the mean of the sum of the squares of differences between adjacent RR intervals, and TP), while in patient group, only association found was between SDNN (HRV time domain parameter) and systolic BRS. On multiple linear regression analysis, the significant independent predictors of systolic BRS in patient group consisted of calcium-phosphate product, BPV, and HRV [Table 5]. Interestingly, this model could explain 35% (adjusted R2 = 0.3456) of the variations in BRS.

Discussion

The salient findings of the present study include that predialytic nondiabetic Stage 4 and 5 CKD patients have reduced BRS, decreased HRV, and higher arterial stiffness than healthy controls.

BRS is an index of overall baroreflex loop functioning, which plays an important role in short-term BP regulation. CKD is associated with metabolic alterations that result in hastened vascular calcification as well as uremic autonomic neuropathy. Few studies have investigated baroreflex function in predialytic CKD patients,[41617] with similar findings to our study that BRS is depressed in these patients. Studies on arterial stiffness indices are in concordance to our results that PWV[181920212223] in CKD Stage 4 and 5 predialytic patients is higher than controls while AI[23] is similar in predialytic patients and controls. On similar grounds, studies on predialytic CKD patients have found a reduction in HRV parameters[24252627] while there is paucity of studies in short-term (5 min) BPV. Recent literature has tried to decipher the mechanism responsible for reduced BRS in CKD patients by exploring the relationship between vascular (arterial stiffness) and neural (HRV) components[7828] in renal transplant recipients and peritoneal dialysis patients.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively study the baroreflex loop function using multiple parameters - BRS, arterial stiffness indices, HRV, and BPV together and decipher their relationship in predialytic CKD patients. We could find only one study in which investigators have assessed BRS and arterial stiffness indices together and discerned their relationship to each other in predialytic CKD patients. Lacy et al., 2006[4] investigated BRS and arterial stiffness indices in 55 nondialysis-dependent nondiabetic CKD Stage 1–5 patients and found that reduced GFR was correlated with decreased BRS and increased PWV. They found no correlation between PWV and BRS. However, this study had not evaluated the neural component of baroreflex (HRV) and also comprised considerably older age group (mean 60 years) in their study. Although, when we combined healthy controls and CKD patients, we found similar correlation between GFR with BRS and PWV, this was lost in patient group alone probably due to narrow spectrum of GFR limited to CKD Stage 4 and 5 and lower sample size in our study. In agreement to their findings, we found no significant correlation of BRS with PWV in both the combined group (healthy controls and CKD patients) and CKD patients alone.

In addition, in the present study, we tried to evaluate the determinants of reduced BRS in CKD patients. Multiple regression analysis in CKD patient group interestingly revealed a model (R2 adjusted = 0.3456) of independent predictors of reduced BRS comprising three variables – increase in calcium-phosphate product, increase in BPV, and decrease in HRV. Thus, at least the results of this study suggest that in predialytic CKD Stage 4 and 5 patients, impaired BRS may be related to autonomic neural involvement (that is reduced HRV). This cannot completely rule out the contribution of arterial stiffness-mediated changes in compliance, resulting in decrease in BRS (although we did not any find any significant association between the two in this population). In addition, the prediction model comprises calcium-phosphate product, which has been found in the previous studies to be associated with increased vascular calcification[29] and this enhanced calcification has been reported to be an independent-positive predictor of PWV.[30] The major strength of the present study lies in the comprehensive multiparametric evaluation of autonomic and vascular functions in relation to BRS in predialytic CKD patients. In addition, selection of a nondiabetic patient group eliminates the confounding influence of diabetes on autonomic and vascular parameters and aids in delineating the direct role of kidney disease per se on the parameters studied. The limitations of the present study are that the regression model lies in the narrow spectrum of CKD (Stage 4 and 5) with a limited sample size of 30.

The findings of the present study suggest that predialytic CKD patients have stiffer arteries (increase in PWV), autonomic neuropathy (reduced HRV), and reduced BRS.

Conclusion

Predialytic nondiabetic CKD Stage 4 and 5 patients had higher PWV, lower HRV, and reduced BRS than healthy controls. Reduced HRV and altered calcium-phosphate homeostasis emerged to be significant independent predictors of reduced BRS.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mild renal insufficiency is associated with increased cardiovascular mortality: The Hoorn Study. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1402-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and risk factors of atherosclerotic cardiovascular accidents in predialysis chronic renal failure patients: A prospective study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2597-602.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduced glomerular filtration rate in pre-dialysis non-diabetic chronic kidney disease patients is associated with impaired baroreceptor sensitivity and reduced vascular compliance. Clin Sci (Lond). 2006;110:101-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduced baroreflex sensitivity is associated with increased vascular calcification and arterial stiffness. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1140-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Restoration of baroreflex function in patients with end-stage renal disease after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1305-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of impaired baroreflex sensitivity and increased arterial stiffness in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2016;20:302-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal transplantation normalizes baroreflex sensitivity through improvement in central arterial stiffness. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2645-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute effect of haemodialysis on arterial stiffness: Membrane bioincompatibility? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:2797-802.

- [Google Scholar]

- Contribution of volume overload and angiotensin II to the increased pulse wave velocity of hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:177-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with increased arterial stiffness in renal transplant recipients. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:CR301-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- How to measure baroreflex sensitivity: From the cardiovascular laboratory to daily life. J Hypertens. 2000;18:7-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens. 2012;30:445-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulse-wave analysis: Clinical evaluation of a noninvasive, widely applicable method for assessing endothelial function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:147-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of dialysis and renal transplantation on autonomic dysfunction in chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1991;40:489-95.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cardiac baroreceptor sensitivity: A prognostic marker in predialysis chronic kidney disease patients? Kidney Int. 2005;67:1019-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arterial stiffness in predialysis patients with uremia. Kidney Int. 2004;65:936-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stepwise increase in arterial stiffness corresponding with the stages of chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:494-501.

- [Google Scholar]

- Arterial stiffness and enlargement in mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2006;69:350-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Increased aortic wall stiffness associated with low circulating fetuin A and high C-reactive protein in predialysis patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2009;113:c81-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pulse wave velocity and vascular calcification at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J Hypertens. 2010;28:163-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of volume status and arterial stiffness in chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2014;36:28-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heart rate variability is decreased in chronic kidney disease but may improve with hemoglobin normalization. J Nephrol. 2008;21:45-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heart rate variability in advanced chronic kidney disease with or without diabetes: Midterm effects of the initiation of chronic haemodialysis therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:3749-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Depressed cardiac autonomic modulation in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Bras Nefrol. 2014;36:155-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Relationship between heart rate variability and pulse wave velocity and their association with patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Clin Nephrol. 2014;81:9-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Baroreflex sensitivity after kidney transplantation: Arterial or neural improvement? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:2401-3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1478-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Associations between vascular calcification, arterial stiffness and bone mineral density in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:586-93.

- [Google Scholar]