Translate this page into:

Social Media and Organ Donation: Pros and Cons

Address for correspondence: Prof. Sanjay K. Agarwal, Department of Nephrology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India. E-mail: skagarwalnephro@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Shortage of organ donors is the most important obstacle standing in the way of lifesaving organ transplantation in a myriad of patients suffering from end-stage organ failure. It is vital that the transplant societies and associated appropriate authorities develop strategies to overcome the unmet needs for organ donation. The power of prominent social media (SoMe) platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, which reach millions of people, can increase awareness, provide education, and may ameliorate the pessimism toward organ donation among the general population. Additionally, public solicitation of organs may be helpful for waitlisted candidates for organ transplantation, who cannot find a suitable donor among near relations. However, the use of SoMe for organ donation has several ethical issues. This review attempts to highlight the advantages and limitations of using social media in the context of organ donation for transplantation. Some suggestions on the best utilization of social media platforms for organ donation while balancing ethical considerations have been highlighted here.

Keywords

Coercion

organ donation

social media

transplantation

Introduction

Over the past few decades, the emergence of social media (SoMe) has revolutionized our information and communication strategies. Easy and affordable access to the internet has made it a convenient mode of communication. when compared to conventional print media (magazines, newsletters, newspapers, and leaflets), electronic media, and radio broadcasts have been largely replaced by platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.[1,2] While SoMe can play a constructive role in increasing public awareness, collecting views, and spreading righteous information about organ donation in the general population, its use can have disadvantages.[3] SoMe platforms, especially Facebook, are being used by patients and their relatives to identify potential organ donors.[4] Transplantation is a complex and highly regulated area of the health-care sector, enforced through stringent legislation. Independent solicitation for organs on SoMe can undermine the laws regulating transplant and result in inadvertent harm to patients and the current transplantation system. The field of medicine is susceptible to serious consequences such as misinformation, false claims, financial scams, coercion, and manipulations resulting from the malicious use of SoMe.[5] Further, SoMe usage in organ transplantation has several ethical implications. We hereby review the advantages and limitations of utilizing SoMe for organ transplantation, focusing on ethical issues.

Globalization and outreach of SoMe

SoMe is currently an integral part of the daily routine and personal lives of almost everyone, and its use has skyrocketed over the past few decades. According to a recent survey, as of 2021, over 4 billion people use SoMe worldwide, with the average user engaging in 8.6 accounts on different networking platforms.[6] YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter are the most widely used SoMe platforms. However, Instagram, LinkedIn, and Pinterest engage several million users as well. The use of these platforms depends on multiple factors, such as age, gender, and educational level, and is especially popular among the younger generation. Facebook has roughly 2.6 billion active users per month worldwide, while Twitter, yet another internet-based SoMe platform, engages over 350 million active users per month.[7] A total of 10 billion hours are spent on various SoMe platforms per day.[7] Various professional organizations, news channels, academicians, scientists, and many political leaders use Twitter to connect with the general public.[8] Social networks have also evolved from being a smooth means of keeping in touch with relatives and friends to having a substantial impact on the society in more pressing health-related issues, including organ donation and transplantation.

SoMe as a tool in organ donation

In the context of organ transplantation, SoMe is used to encourage deceased donor registrations, create awareness, disseminate information, and promote communication and social networking. Centers are now leveraging SoMe platforms to increase advertising and endorsement of their transplant programs. Quite often, personal stories and documentaries are posted on SoMe in a heart-warming manner to seek the attention of potential living organ donors, and it is not uncommon to see appalling stories asking for financial help.[9] The information is propagated in numerous forms, including news, texts, images, blogs, animations, or videos. In May 2012, Facebook made some amendments to its US agreements that allowed its users to mention “organ donor” in their profile description, and they were also offered a link to their state registry to complete an official registration, after which their network was made aware of the new status as a donor. This initiative had a considerable impact, resulting in 13,054 new online registrations, representing a 21.1-fold increase on the very first day; however, registrations diminished over the following 2 weeks.[4] Although the facebook effect les to an increase in number of donor registrations, whether it results into a higher number of donation rates is still unclear. Similarly, other SoMe platform-based efforts by Facebook, Twitter, and Tinder supported public advocacy campaigns to boost organ donations.[10] These initiatives make it less complicated for the general population to register as donors and have shown potential in addressing the unmet need for organ donors. Apple and Donate Life America enabled iPhone users to indicate their decision to register as donors in the national registry by launching the registerme.org platform.[11] Recently, the World Sight Day 2020 #idonation campaign on Twitter encouraged people to donate their corneas.[12]

In a survey involving 299 American Society of Transplant Surgeons members, respondents indicated that they use SoMe to communicate and interact with friends and family (76%), other transplant professionals (58%), transplant candidates (15%), recipients (21%), and living organ donors (16%). Interestingly, SoMe was extensively used by its members to spread awareness about the deceased and living donors, share information, and advertise their respective transplant programs.[13] The National Health Services (NHS) also launched an advertising campaign with celebrities to promote organ donation on SoMe.[14]

Disparity in SoMe usage between high- and low-income countries

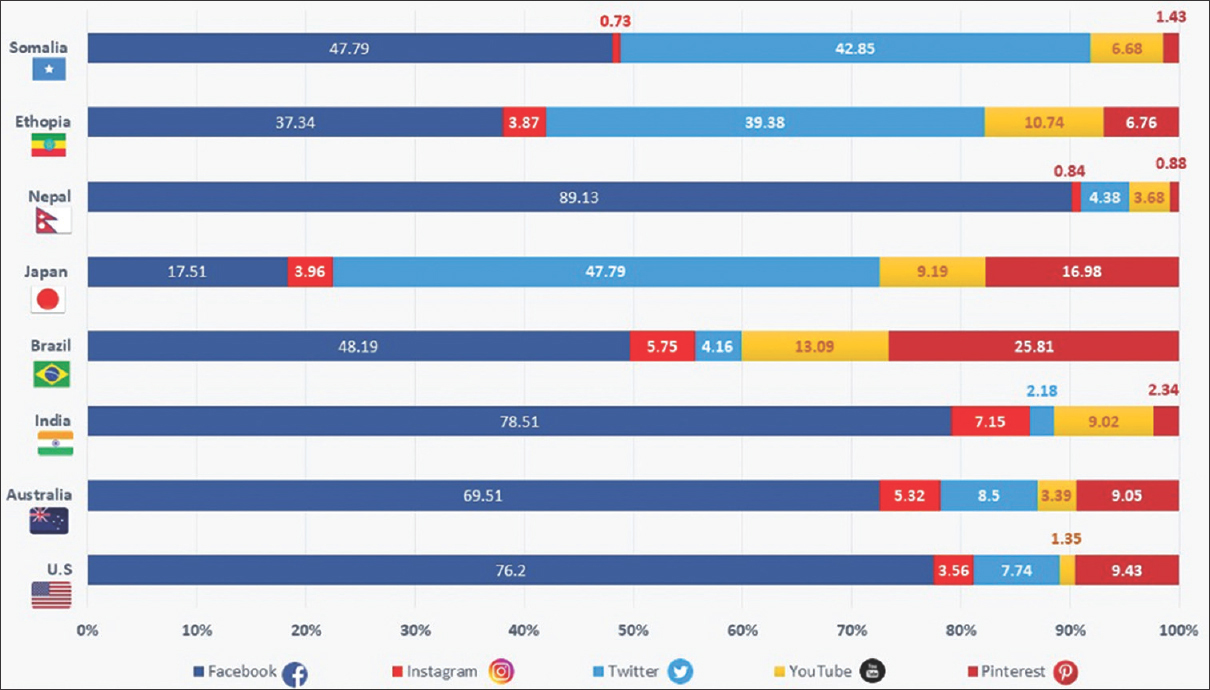

While the use of SoMe is progressively rising, its coverage and influence seem to be more intense in developed countries. Availability and accessibility of the internet have been shown to be consistently related to the gross national income (GNI) per capita of the country. The popularity and usage of SoMe are restricted in low-/middle-income countries (LMICs).[15] Surveys have showcased that over 80% of Americans seek health-related information from social networks,[16] and in the UK, patients take shared-informed decisions by utilizing facilitated communication, positive interactions, and available research data on SoMe.[17] Usage of health issue-related communications and patient education on SoMe platforms are more efficient and cogent in the health-care systems of high-income countries.[15] A statistical analysis based on the number of active SoMe users of the top social networks reported that SoMe penetration was meagre in countries like Nigeria (12%), Kenya (16%), Ghana (19%), and India (23%), when compared to the total population of the countries (as of January 2019).[18] Thus, there is a huge gap between countries in the penetration of internet services. In January 2021, the internet penetration stood at 36.7% in Nepal, whereas it was over 90% in Japan.[19] Figure 1 shows the most popular SoMe platforms around the world as of July 2021. These findings highlight that, strategies for promoting organ donation cannot be implemented in all countries in a similar fashion. There is a need to address the matter on the basis of the target population as well as the resources available. Despite the continuous lag in the number of SoMe users in developing countries, a cross-sectional study from Ghana reported that digital media was the prime source of information in creating awareness and providing knowledge about organ transplantation. Other modalities of information dissemination were lectures and seminars by health-care providers, newspapers, family, and friends.[20] Another study from Uganda also emphasized the effective use of health communication campaigns for health sector empowerment of the community.[21]

- Most used social media platform around the world as of July 2021

Education and awareness versus public organ solicitation

Limited awareness and disinformation in the general population are one of the prominent barriers that deter transplantation. Awareness and education might persuade an individual to consider different perspectives on a matter and increase their engagement and communication. The most important aspect of education and awareness is that it can create a positive attitude and righteous belief in an individual and facilitate a well-informed decision about organ donation with accurate and balanced information. The promotion and raising of awareness can be both aimed to encourage public engagement in organ donation. The general population may be approached to enhance their knowledge regarding organ donation and transplantation through advertising and promotional events, mobile vehicle promotion, television and radio shows, publicity via eminent celebrity involvement, interactive public meeting, theatre shows, public rallies, and increased sponsorship in sports and entertainment events.[22]

Public solicitation of organs involves a recipient or their representative soliciting an organ for transplantation. It can be by means of public broadcast on social network sites (such as Facebook), billboards, advertisements, personal blogs, or announcements. The intended donor and recipient are not likely to have a prior relationship. The motive is to more donors. In a way, public organ solicitation is a reflection of the issue of organ shortage and seeks to gain access to a potential organ that would not otherwise have been available for donation. At the same time, the practice of public solicitations of the organ is unregulated, and thus has concerns. Therefore, it is not allowed in many countries like India. It has been criticized as unfair, as the donation is allowed to the identified recipients rather than to the waiting list recipient. So, there are chances that solicitation bypasses the fair allocation process.

Positive impact of SoMe in organ donation

The most striking feature of SoMe is that the information reaches its target audience instantly without any lag period. Unlike conventional media, SoMe is a two-way communication where there is room for interaction with the audience and organization and among the audience; therefore, the attitude of people can be studied, which cannot be done in traditional media. Information published on SoMe is versatile. It can be modified/edited and updated as information changes something not available to traditional media. Furthermore, the information on SoMe is available and accessible indefinitely, unlike print media where the information is available only once.

Evidence has already suggested a positive impact of SoMe on various health-related issues such as smoking, alcohol abuse, the importance of nutrition and exercise, and the role of medical screenings.[23] SoMe is an effective means of educating and creating awareness for organ donation. Undoubtedly, organ transplantation is the best treatment modality for patients with end-stage organ failure.[24] However, the shortage of organ donors globally creates a substantial unmet need for organs. Statistically speaking, every 9 min, a person is added to the existing transplant waiting list, and 17 people die each day waiting for an organ transplant.[25] SoMe can be fairly utilized for public education, deceased donor registration, advocacy, and supporting donors and recipients, especially in LMICs. Regular dissemination of facts regarding organ donation and engaging the common public can be a suitable approach to educate people and bust common myths. Sharing stories of waitlisted candidates, experiences from prior living donors, testimonials, simplifying the instructions, answering queries on how to register for organ donation, and posting recent research findings related to transplantation can facilitate the education of the general public on SoMe.

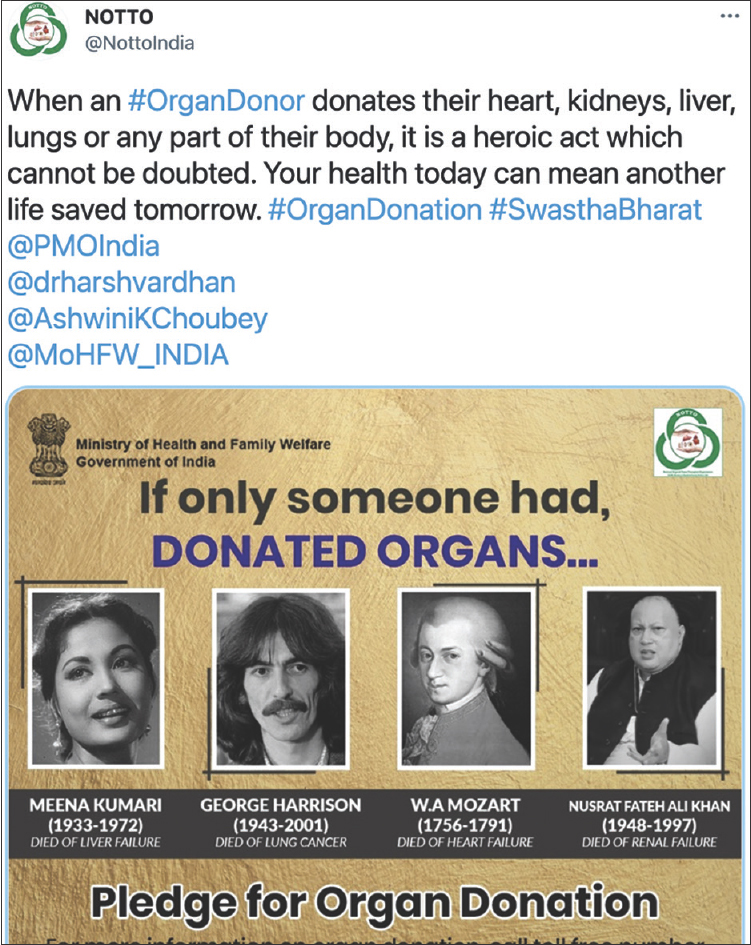

Figure 2 shows an example of the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization (NOTTO) spreading organ donation awareness using SoMe. In high-income countries, an increase in the number of non-directed organ donors can have a profound impact. For instance, such donors can initiate a chain of living kidney donations. Such a noble act would also encourage other donors to come forward and pledge for organ donation. Such initiatives grant hope to the waiting list candidates who cannot find an eligible donor among their near relations. But these practices are only applicable in some countries like the USA and are not considered legal in developing nations such as India. DuBray et al.[26] retrospectively investigated self-referrals for living kidney donations and compared individuals petitioned through SoMe versus verbal communication. Notably, half of the respondents had an altruistic relationship, and the majority (94%) of these were petitioned through SoMe.

- An example of NOTTO spreading organ donation awareness using social media. NOTTO = National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization

Despite the technological advancement in communication, there is still a remarkable knowledge gap and a persisting negative attitude about organ donation in the general population; however, this can be overcome.[27] Figure 3 shows the positive influence of SoMe on organ donation. A survey to assess the use of Twitter in communicating information about living solid organ donation found that 16% of the users who identified themselves as organ donors had already shared educational and motivational information about organ donation and transplantation in their profiles.[28] A meta-analysis showed that media campaigns on organ donation awareness resulted in an overall 5% augmentation of outcomes, such as donor registry sign-ups.[29] DONOR (www.thedonorapp.com) is another internet-based application designed to be used on smartphones, enabling transplanted candidates to use SoMe to share their stories on living organ donor and seek living organ donations.[30]

- Positive influence of social media on organ donation

The flipside of SoMe usage in organ donation

The use of SoMe in organ donation has some logistic and ethical implications too. It should not be underestimated that if not used with regulations, issues such as coercion, organ trading, financial fraud, public shaming, and breaches of the integrity of the national transplantation program can arise from SoMe involvement.[5,31]

-

Breach of donor/recipient confidentiality and privacy:

Confidentiality and privacy are challenged while contending with the SoMe use. For instance, in deceased donations, information is protected, and organ procurement organizations (OPOs) share only relevant information about the recipient to the donor families. Similarly, altruistic living donors are provided with limited required information about the recipients. However, with the widespread use of SoMe information, anonymity and confidentiality may be compromised.[5]

-

Likelihood of sharing misinformation

As individuals are free to choose the content of medical or personal information on SoMe, there are concerns about sharing misinformation to influence potential living donors. Moreover, the information shared may not be accurate. With disinformation, there is a high chance that the Samaritans’ pursuit of living organ donation would be based on the persuasiveness of the solicitor’s appeal rather than the more relevant clinical information. A study that examined 224 profiles of potential kidney transplant recipients who registered on a donor-matching internet site found that solicitors shared only a few sociodemographic and medical details other than the blood group type, gender, and region.[32] Such considerable variability in the revealed information highlights the inherent ethical issues with the public solicitation of living donors on SoMe.

-

Influence and coercion

Personal stories shared on SoMe to solicit organs can be misleading and bias the donors to offer their organs to solicitors rather than make an independent decision to give higher priority to those in greatest need.[33] In an analysis by Rodrigue et al.,[32] concerns were raised that some participants even intended to hire a marketing consultant to make their profile more enticing to potential living donors. There was an inclination to hide information like ethnicity, appearance, and body mass index. Such selective disclosure of information may increase the chances of obtaining favourable responses from potential donors and impede making a well-informed independent decision. Sharing personal information on SoMe through posts or personal messages can even result in circumstances such as converting an altruistic donation into a directed one.

-

Problems with an informed consent

Obtaining a well-informed consent before proceeding with organ donation is a crucial step. Donors should be well informed about the short- and long-term complications of organ donation, expenses, and post-surgery recovery. Unfortunately, most public organ solicitations fail to disclose such important information that may influence the decisions of potential donors.

-

Negative perception

Public organ solicitation and malicious use of SoMe for organ donation could also lead the general public to doubt the integrity of the entire transplantation system, which is otherwise a complex and highly regulated system. The fear of organ trafficking, health hazards, suspicion of recipients’ ulterior motives, and insider trading may discourage potential donors from registering.[34] Information failing to adequately explain the entire process could add to this mistrust.[35] On SoMe, information becomes viral instantly to a colossal audience, and thus carries the risk of spreading information rapidly. Dissemination of even a single misinformation may have huge impact and can negatively affect attitude of the people toward organ transplantation.

-

Discrimination

A large proportion of SoMe users belong to a higher socioeconomic stratum, which is more educated, wealthier, and can afford to use SoMe more persuasively.[36] Similarly, some recipient–donor matching websites demand fees to create and publish profile. So, individuals who can afford to pay such fees have more access to donors.[37] This inequity due to economic disparities could lead to discrimination and increase the likelihood of exploitation of potential donors that those in greater need could have otherwise used.

-

Fear of financial scams and organ trafficking

The use of SoMe is unrestricted and unregulated by demographics, and thus, there is an added risk of illegal and unethical practices such as organ trade/trafficking in the realm of organ procurement between LMICs and developed nations, in addition to the risks of financial scams.

Laws on public solicitation of organs in different countries

The practice of public solicitation of organs and SoMe usage for organ transplantation varies markedly in different parts of the world. In European countries, the practice of organ donation public solicitation is less frequent. Ethical, Legal, and Psychosocial Aspects of Transplantation (ELPAT) section of the European Society for Organ Transplantation working group has addressed the issue and given a definition for solicited living organ donation. The working group defined it as solicited “specified donation,” whereby an organ is donated directly to the recipient specified in the public solicitation, without being related to that person (emotionally or genetically).[38] The majority of European countries including Germany, France, and Greece do not allow unspecified donation, thus precluding organ donation from donors who respond to the public solicitation. Moreover, even in countries like the UK or the Netherlands which permit unspecified living donation, transplant centers remain unaccommodating toward donation resulting from the public solicitation. As per the Human Tissue Act 2004 and the Human Tissue (Scotland) Act 2006, in the UK, it is not illegal to seek a living organ donor, online or in a newspaper, providing the condition that no offering of any reward, payment, or material advantage to the potential donor is involved. If any recipient intends to do so, he/she should consult his transplant unit.[39] Moreover, in an ELPAT view, paper recommendations were made that as long as donor shortage persists, the patients who do not have a living kidney donor or are at very less likely chance of finding a suitable donor, for instance, highly sensitized patients, should not be condemned if they decide to publicly solicit for a live donor.[38]

In the USA, transplant centers often accept organs from living donors who come forward following public solicitation. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN)/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) provides minimal regulatory guidance on the appropriate usage of SoMe for live donor solicitation, stating that organ transplant policy developers and centers should continuously re-evaluate the new developments in communication methods available to the community, however, it is crucial to re-examine the living donor/candidate relationships.[40] A position paper by the Canadian Society of Transplantation concluded that organ transplantation with living donors who respond to public organ solicitation is legally and ethically acceptable if done in compliance with Canadian law, and there is no evidence suggestive of organ trafficking or monetary or material rewards.[41] In contrary to this, such practices are precluded from countries like India as an altruistic non-directed donation is not permitted.

By the provided recommendations regarding public organ solicitations from different countries, it can be inferred that it is crucial for all transplant program centers to be transparent about their policies and evaluation procedures for solicited living organ donors. To maximize the impact of SoMe campaigns on organ donation and make it more ethically acceptable, re-evaluating the intentions behind any public organ solicitation is essential. Psychosocial assessment of live donors and an intensive evaluation of the motivation of potential donors should be a standard practice. Appropriate organizations and authorities should adopt newer methods such as developing new online real-time monitoring tools to assess and examine the attitude of general population toward organ donation, thereby regulating and modifying the campaign as and when needed. It is crucial to lay strict regulations to use SoMe as a tool for creating organ donation awareness and not as an organ-matching tool, before the widespread use of SoMe for organ donation.

The Indian scenario

There were 467.0 million SoMe users in India as of January 2022, which is equivalent to 33.4% of the total Indian population. Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and LinkedIn’s advertisement reach was equivalent to 23.5%, 33.4%, 16.4%, and 5.9%, respectively, of the total population of India at the start of 2022.[7] Despite the high usage of SoMe, the awareness and education regarding organ donation in India are lacking, and the usage of SoMe varies according to the socioeconomic status of the population. There is an immense hesitation about organ donation, contributing to an abysmally low deceased donation rate of 0.05–0.08/million population.[42] A survey of 900 clinic attendees and kin of dialysis patients showed that 44.2% were unaware of the organ donation law. In 32% of people, the source of information was a doctor or hospital brochures. Others obtained information from television (12.4%) and newspapers (24.8%). Only 4% of people received information from the internet.[43] Organizations such as MOHAN Foundation, a nongovernment, non-profit organization, are continuously engaged in activities of promoting awareness about organ transplantation among the general public through interactive meetings.[22] Politicians and celebrities including actors and cricket players have been frequently seen to be involved with the organization in promoting the noble cause of organ donation.[22] Offline events such as marathons, rallies, distribution of donor cards, and public shows can be broadcast on SoMe to increase the outreach and target audience. For instance, tweets of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s “Mann Ki Baat” session that emphasized the need for organ donation received a colossal response from the Twitter community. To constrain the illegal unrelated donation activities, donations between unrelated individuals are highly discouraged in the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA), which precludes the use of SoMe for public solicitation of potential donors in India.[44] Sensitization of the general population about organ donation after death is one of the important measures to improve the donation rates in the country. Implementing strategies such as dispersing accurate, clear, and focused messages and preparing an ethically guided framework could be applied to avoid ethical dilemmas.[45] Unregulated use of SoMe for organ transplantation by individual institutions may be interpreted as advertisement, and hence may induce mistrust among public. At present, creation of awareness by SoMe must be done only by the appropriate authority in transplant and restricted to deceased donation in the Indian scenario.

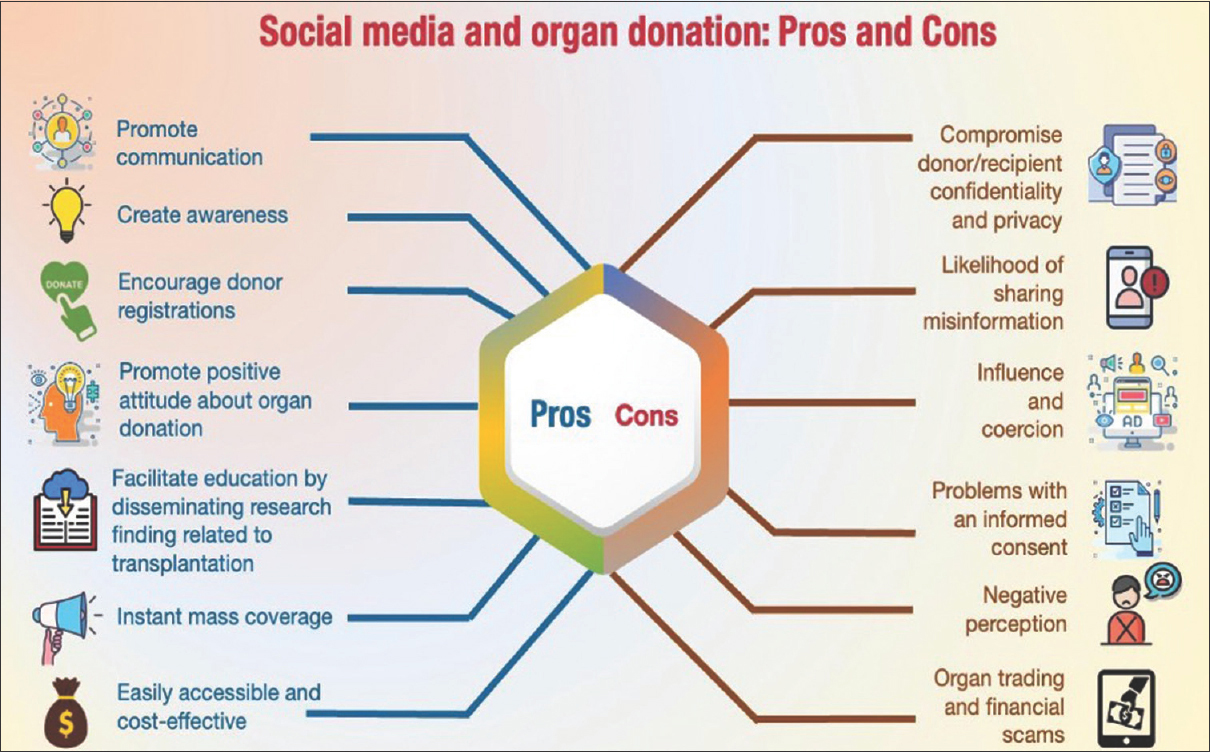

Figure 4 summarizes the pros and cons of using SoMe in organ transplantation.

- Summary of pros and cons of using social media in organ transplantation

Conclusion

Worldwide, the requirement for organ transplants greatly outpaces the supply. Newer strategies are required to redress the demand–supply mismatch situation in organ transplantation, and SoMe is an effective tool for establishing communication between transplant centers, transplant networks, transplant candidates, and potential donors. It will be fascinating to use it in propagating the latest research in the field of organ transplantation and to help waitlist candidates and potential donors make a well-informed decision. If used with continuous monitoring without undermining regulatory guidelines and implementing ethical considerations, SoMe platforms can help spread considerable awareness regarding living and deceased kidney donation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Critical analysis of communication strategies in public health promotion: An empirical-ethical study on organ donation in Germany. Bioethics. 2021;35:161-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effective uses of social media in public health and medicine: A-systematic review of systematic reviews. Online J Public Health Inform. 2018;10:e215.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social media and organ donor registration: The Facebook effect. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2059-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social media and organ donation: Ethically navigating the next frontier. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:2803-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social Media Use. 2021. Pew Research Center. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/

- [Google Scholar]

- Global social media stats. Available from:https://datareportal.com/social-media-users

- Interviews of living kidney donors to assess donation-related concerns and information-gathering practices. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:130.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facebook and Twitter join US effort to attract a million new organ donor registrations. BMJ. 2016;353:i3369.

- [Google Scholar]

- Apple &Donate Life America bring national organ donor registration to iPhone 2016. Available from:https://www.apple.com/in/newsroom/2016/07/05Apple-Donate-Life-America-Bring-National-Organ-Donor-Registration-to-iPhone/

- NHSBT launches #IDonation Twitter campaign for World Sight Day to highlight ongoing need for cornea donors. Available from:https://www.nlg.nhs.uk/news/nhsbt-launches-idonation-twitter-campaign-for-world-sight-day-to-highlight-ongoing-need-for-cornea-donors/

- How should social media be used in transplantation?A survey of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. Transplantation. 2019;103:573-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- 4.NHS Organ Donation Campaign Post for Donate Life Concert:NHS Organ Donation Campaign 2013. Available from:https://www.facebook.com/organdonationuk/posts/10151407731386816

- High-quality health systems:Time for a revolution in research and research funding. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e303-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- “I can also serve as an inspiration”:A-qualitative study of the TB&Me blogging experience and its role in MDR-TB treatment. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108591.

- [Google Scholar]

- Which countries use social media the most and why 2019. Available from:https://www.languageinsight.com/blog/2019/countries-use-social-media-the-most/

- [Google Scholar]

- Social Media Stats Worldwide. :[Last accessed on 2021]. Available from:https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats

- The internet use for health information seeking among Ghanaian University students:A-cross-sectional study. Int J Telemed Appl. 2017;2017:1756473.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing Uganda's Public Communications Campaigns Strategy for Effective National Health Policy Awareness, 2009

- MOHAN Foundation Organises a Masterclass on Social Media for Organ Donation and Transplantation. Available from:https://www.mohanfoundation.org/activities/MOHAN-Foundation-Organises-a-Masterclass-on-Social-Media-for-Organ-Donation-and-Transplantation-6323.htm

- The role of social network technologies in online health promotion:A-narrative review of theoretical and empirical factors influencing intervention effectiveness. J-Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Survival benefit of solid-organ transplant in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:252-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Available from:organdonor.gov

- Impact of social media on self-referral patterns for living kidney donation. Kidney. 2020;360:1419-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organ donation awareness: Rethinking media campaigns. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7:1165-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Use of Twitter in communicating living solid organ donation information to the public: An exploratory study of living donors and transplant professionals. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13447.

- [Google Scholar]

- A-meta-analytic review of communication campaigns to promote organ donation. Commun Rep. 2009;2:63-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social media and kidney transplant donation in the United States: Clinical and ethical considerations when seeking a living donor. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:583-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ethical complexities of online organ solicitation via donor-patient websites: Avoiding the “beauty contest”. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:43-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Web-based requests for living organ donors: Who are the solicitors?Clin Transplant. . 2008;22:749-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Family discussions about organ donation: How the media influences opinions about donation decisions. Clin Transplant. 2005;19:674-82.

- [Google Scholar]

- Examining the association between media coverage of organ donation and organ transplantation rates. Clin Transplant. 2007;21:219-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Entertainment-(mis) education:The framing of organ donation in entertainment television. Health Commun. 2007;22:143-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Changing patterns of social media use?A population-level study of Finland. Univ Access Inf Soc. 2020;19:603-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dealing with public solicitation of organs from living donors—An ELPAT view. Transplantation. 2015;99:2210-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- The UK Human Tissue Act and consent:Surrendering a fundamental principle to transplantation needs? J Med Ethics. 2006;32:283-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Direction of the organ procurement and transplantation network and united network for organ sharing regarding the oversight of live donor transplantation and solicitation for organs. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:37-40.

- [Google Scholar]

- Public solicitation of anonymous organ donors: A-position paper by the Canadian Society of Transplantation. Transplantation. 2017;101:17-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organ donation in India:Scarcity in abundance. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61:299-301.

- [Google Scholar]

- Why poor organ donation?A survey with focus on way of thinking and orientation about organ donation among clinic attendees and dialysis patients relatives. Transplantation. 2017;101:S75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transplantation of human organs and tissues Act-“Simplified”. Indian J Transplant. 2018;12:84-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Social media and organ donation-A narrative review. Indian J Transplant. 2021;15:139-46.

- [Google Scholar]