Translate this page into:

Strongyloides Stercoralis Infection Mimicking Relapse of ANCA Vasculitis

Corresponding author: Narayan Prasad, Department of Nephrology, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences (SGPGIMS), Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. Email: narayan.nephro@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Meyyappan J, Prasad N, Husain S, Veeranki V, Patel MR, Kushwaha RS, et al. Strongyloides Stercoralis Infection Mimicking Relapse of ANCA Vasculitis. Indian J Nephrol. 2025;35:430-2. doi: 10.25259/IJN_23_2024

Abstract

A 48-year-old female with anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, initially responded well to standard therapy but later presented with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH), simulating disease relapse. Following renal remission with standard immunosuppressive therapy, the patient exhibited fever, hemoptysis, and declining renal function, suggestive of a relapse. Bronchoscopy revealed DAH, raising concern for vasculitis exacerbation. However, discordant laboratory findings prompted scrutiny, leading to the detection of Strongyloides larvae in bronchoalveolar lavage.

Keywords

Anthelminthic therapy

ANCA vasculitis

Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage

Misdiagnosis

Strongyloides stercoralis

Introduction

Treatment of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) requires intense immunosuppression, and approximately 30% of patients show relapse during the course of the disease.1 Although a rise in ANCA titers can sometimes precede a relapse, it’s not a consistent indicator. Given its capacity to affect multiple organs, severe complications like renal failure, pulmonary hemorrhage, CNS vasculitis, or mesenteric ischemia can pose life-threatening risks. It’s crucial to be vigilant about conditions that mimic vasculitis because mistaking them for vasculitis relapse may lead to increased immunosuppression, while these mimics, often stemming from infections, can exacerbate and become fatal when treated with immunosuppressive therapies.2

Case Report

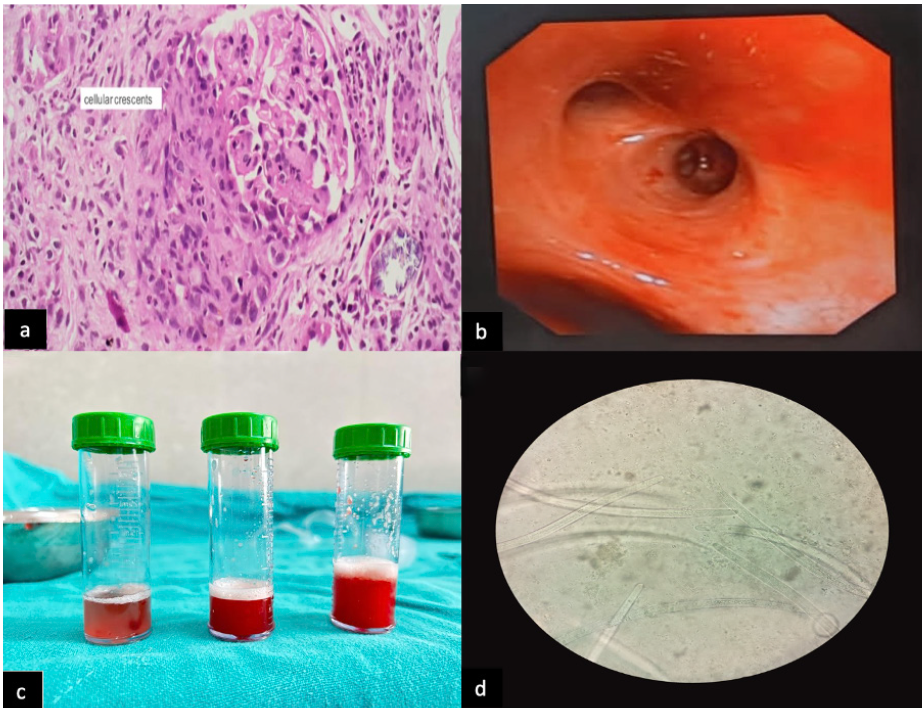

A 48-year-old female presented with a history of loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and progressive renal dysfunction with serum creatinine of 7.2 mg/dl three months ago. Diagnostic workup revealed active urinary sediments, anti-MPO titer >100 IU/ml [Table 1]. Renal biopsy was suggestive of pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis (PICGN) with moderate interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy (IFTA) [Figure 1a]. She was diagnosed with renal-limited PICGN, initially treated with intravenous methylprednisolone 500 mg daily for three days followed by oral steroids 0.5 mg/kg/day and oral cyclophosphamide (1.5 mg/kg/day). She attained renal remission on day 15 and was discharged from hospital.

| Index admission | Follow-up day 7 | Follow-up day 15 | Follow-up day 30 | Follow-up day 75 | Day 88 readmission | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb, g/dl | 8.4 | 9.1 | 9.0 | 10.4 | 12.1 | 8.4 |

| TLC,*103/mm3 | 18.9 | 21.1 | 9.4 | 7.9 | 2.8 | 4.2 |

| Platelet count,*103/mm3 | 412 | 230 | 312 | 180 | 102 | 130 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 7.2 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 2.3 |

| Urine RBCs/hpf | 50-60 | 30-40 | 10-12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 24-hour urine proteinuria (grams/day) | 1.8 | - | 0.8 | - | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Anti-MPO, IU/ml | >100 | - | 36 | <3.0 | - | <3.0 |

| Anti-PR3, IU/ml | <3.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Anti-GBM, IU/ml | <4.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

Hb: Hemoglobin, TLC: Total leucocyte count, RBC: Red blood cells, MPO: Myeloperoxidase, PR3: Proteinase 3, GBM: Glomerular basement membrane

- (a) Histopathological Examination (H/P E) of renal biopsy showing cellular crescent (Index admission) High power view (40x). (b) Image of bronchoscopy showing alveolar hemorrhage (day 90 follow-up, on readmission). (c) Broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) sequential lavage fluid samples suggestive of DAH (day 90 follow-up). (d) Cytopathological examination of BAL fluid showing larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis (40x).

On follow-up days, 30, 45, and 60, the patient continued to be in renal remission with no drug-related adverse events [Table 1]. On day 75, the patient had leukopenia and hence, oral cyclophosphamide induction therapy had to be interrupted. She was continued on tapering dose of prednisolone.

On day 90, the patient presented with fever, exertional intolerance, and cough. There was worsening of creatinine to 2.4 mg/dl. The patient was admitted with a provisional diagnosis of relapse of ANCA vasculitis. While in the hospital, she developed hemoptysis and a progressive fall in hemoglobin was noticed. Chest X-ray was normal, but high-resolution CT was suggestive of alveolar hemorrhage. A clinical diagnosis of diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) was made, which was supported by a rise in DLCO levels. Relapse of ANCA vasculitis was considered initially; however, the anti-MPO titer was less than 3 IU/ml and urinalysis was normal. Due to this discrepancy, she was subjected to bronchoscopy [Figure 1b], demonstrating blood throughout the trachea-bronchial tree which confirmed the diagnosis of DAH [Figure 1c]. The patient’s clinical condition continued to deteriorate—oxygen saturation at ambient air was 75% and she required high-flow oxygen. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) washings were subjected to microbiological analysis which revealed Strongyloides stercoralis larvae [Figure 1d].

The patient was treated with albendazole 400 mg per oral once daily and ivermectin 12 mcg per oral daily for three days. Patient showed rapid clinical improvement. Within three days, the patient’s oxygen saturation improved significantly, allowing discharge. Follow-up at one month demonstrated sustained recovery without respiratory symptoms. Patient continued to be in renal remission.

Discussion

In tropical regions, parasitic infections are relatively common, yet occurrences of strongyloides hyperinfection are infrequent. Although vasculitis is typically prompted by viral or bacterial infections, parasitic infections can incite this condition. In this particular case, the patient exhibited symptoms indicative of pulmonary capillaritis, including hemoptysis and rise in creatinine, mimicking a relapse.

The seroprevalence of Strongyloidiasis may be as high as 30% in some parts of India, and with a worldwide prevalence of 30 million, it is a neglected tropical disease.3,4 The organism’s filariform larvae penetrate the skin, enter the bloodstream, and may disseminate to organs such as the gastrointestinal tract and lungs. Autoinfection by rhabditiform larvae can result in a hyperinfection syndrome, especially in individuals with compromised immune systems, such as in our patient receiving immunosuppressive therapy. We have previously documented a case of fatal Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome, underscoring the importance of timely diagnosis, as delayed identification contributed to the patient’s demise.5

The identification of Strongyloides stercoralis larvae in BAL washings was unexpected yet pivotal in redirecting the treatment strategy. Strongyloidiasis, a potentially life-threatening parasitic infection, can present with pulmonary manifestations mimicking DAH,6 leading to diagnostic challenges, especially in the context of a patient with underlying vasculitis.

This case underscores the diagnostic challenges posed by overlapping clinical presentations of ANCA vasculitis relapse and Strongyloidiasis. It emphasizes the importance of considering parasitic infections in vasculitis-suspected cases, especially in tropical countries, to prevent misdiagnosis and ensure timely therapy, ultimately leading to favorable patient outcomes.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Relapse in anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;5:7-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Severe strongyloidiasis and systemic vasculitis: Comorbidity, association or both? Case-based review. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:2315-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seroprevalence of strongyloides stercoralis infection in a South Indian adult population. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022;16:e0010561.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Strongyloidiasis—the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:967-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatal strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in a renal allograft recipient: A case report and review of literature. Indian Journal of Transplantation. 2014;8:63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hyperinfective strongyloidiasis in the medical ward: Review of 27 cases in 5 years. Southern Medical Journal. 2002;95:711-7.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]