Translate this page into:

ABO-incompatible Repeat Kidney Transplantation: Coping with the ‘Twin Immunological Barrier’

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

A repeat renal transplantation is believed to confer the best survival advantage for allograft failure. The scarcity of matching donors at one end, coupled with the expanding pool of ABO-incompatible (ABOi) donors at the other end, lead us to consider the option of ABOi kidney re-transplantation. However, ABOi kidney re-transplantation is associated with heightened immunological risk due to the presence of two substantial immunological barriers. Concern, queries, and uncertainty exist over the course and outcome of this option. We prospectively studied five patients who underwent live-related ABOi re-transplantation after a failed previous transplant. Four patients (mean age 40.8 ± 6.6 years, 4 males) underwent a second renal transplant, whereas one patient had a third renal transplant. All patients received desensitization with rituximab, plasmapheresis, and intravenous immunoglobulin as per routine protocol. One patient required immunoadsorption to achieve the desired Anti-ABO titer. All five patients had good graft survival. One of them developed combined antibody and cell-mediated rejection and another antibody-mediated rejection. Live-related ABOi kidney re-transplantation could be a viable option for patients with a previously failed graft.

Keywords

ABO-incompatible

desensitization

outcome

plasmapheresis

re-transplantation

Introduction

Renal transplantation (RT) is undoubtedly the best modality of renal replacement therapy. Highly sensitized patients awaiting a transplant constitute a challenging subgroup. Patients with a previously failed allograft are believed to be sensitized.[1] A repeat RT offers the best chances at survival for this group of patients and also seems to be the cost-effective option compared to remaining on dialysis. According to the UNOS registry data, the 1-year and 5-year survival rates are 88% and 65% for repeat RT compared to 91% and 70%, respectively, for first RT.[2] However, the unavailability of a compatible donor presents a potential hurdle. The past decade has seen the evolution of ABO-incompatible (ABOi) RT, providing an invaluable expanding pool of donors for the ESRD patient. The number of ABOi-RT has been increasing worldwide with the comparable result to ABO compatible (ABOc) transplantation in the long term.[3456] Advances in desensitization protocols have made ABOiRT a plausible reality.[45]

A challenge and genuine concern face the clinician when an ABOi is to be done in a patient with a previously failed graft. ABOi and HLA incompatibility (HLAi) are two strong immunological barriers that stand in the way of an ABOi repeat RT. We prospectively followed up the outcomes of five patients with a previously failed graft who underwent Live-related ABOiRT at our tertiary care center between 2013 and 2018. Table 1 summarizes the details and outcomes of the cases. Of the 5 cases, 4 patients underwent a second renal transplant, and one patient (Case 2) a third RT. The mean age was 40.8 ± 6.6 years, and four were male. The previous graft survival ranged from 10 months to 12 years (mean 334 ± 49.7 months). The native kidney disease was presumed chronic interstitial nephritis in two patients and presumed chronic glomerulonephritis in three patients. The immunological risk assessment of the patients is shown in Table 2. CDC cross-match was negative in all patients at the time of transplantation. All patients had pre-transplantation anti-ABO titer evaluation [Table 2].

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Sex | 30 y/Male | 44 y/Female | 46 y/Male | 39 y/Male | 45 y/Male |

| Native kidney disease | CIN | CGN | CIN | CGN | CGN HCV positive treated with DAA |

| Previous graft survival | 10 months | 24 months | 11 years | 7 years | 7 years |

| Donor | Mother | Mother | Wife | Wife | Wife |

| Donor kidney GFR (kidney transplanted) (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 38 | 43 | 73 | 44 | 55 |

| Donor blood group | AB+ | B+ | B- | AB+ | A+ |

| Patient blood group | B+ | O+ | A+ | O+ | B+ |

| HLA match | 3/6 | 4/6 | 1/6 | 1/6 | 3/6 |

| Post Transplant Maximum Anti ABO titre in 1st week | Anti A IgG: NIL | Anti B IgG: 4 | Anti B IgG: 4 | Anti A IgG: 16 Anti B IgG: 16 |

Anti A IgG: 2 |

| Post-transplant Maximum Anti ABO titre in 2nd week | Anti A IgG: NIL | Anti B IgG: 4 | Anti B IgG: 4 | Anti A IgG: 8 Anti B IgG: 8 |

Anti A IgG: 4 |

| Rejection episodes | None | None | ABMR-1 episode | Combined rejection - 1 episode | None |

| Treatment response | N/a | N/a | Complete response | Complete response | N/a |

| Infectious episodes | None | None | UTI: 4 episodes | None | Viral fever: 1 episode |

| Other complications | 1. Post transplant Hyperglycemia 2. Leucopenia |

None | None | Thrombocytopenia (Drug induced) TB Meningitis Septic shock |

Perigraft collection-managed conservatively |

| Baseline creatinine | 1.38 mg/dL | 0.77 mg/dL | 0.8 | 1.05 | 0.8 mg/dL |

| Last documented creatinine | 1.95 mg/dL | 0.79 mg/dL | 1.11 | 2.11 | 1.09 mg/dL |

| Follow up duration | 54 months | 84 months | 28 months | 65 days (Expired) | 24 months |

CIN, chronic interstitial nephritis; GCN, chronic glomerulonephritis; ABMR, acute antibody mediated rejections; UTI, urinary tract infection; GFR-Glomerular filtration rate; HLA, histocompatible antigen; DAA-Directly acting antivirals [used for the treatment of Hepatitis C]

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC Crossmatch | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Pre-transplant | T-FXM: Neg | N/a | T-FXM: Pos | T-FXM: Neg | T-FXM: Neg |

| Flow crossmatch | B-FXM: Neg | B-FXM: Pos | B-FXM: Pos | B-FXM: Neg | |

| Pre transplant DSA | Class1-Neg Class2-Neg |

Class1-Neg Class2-Neg |

Class1-Neg Class2-Neg |

Class1-Neg Class2-Neg |

Class 1-Pos (MFI-1250) Class 2-Neg |

| Baseline Anti ABO antibody titre | Anti A IgG: 32 | Anti B IgG: 256 | Anti B IgG: 8 | Anti A IgG: 512 Anti B IgG: 512 |

Anti A IgG: 32 |

| Anti ABO antobody titre (Pre Transplant) | Anti A IgG: NIL | Anti B IgG: 4 | Anti B IgG: 2 | Anti A IgG: 8 Anti B IgG: 8 |

Anti A igG: NIL |

| Desensitization method | RTX, MMF, Tac, PP + IVIG | RTX, MMF, Tac, PP + IVIG | RTX, MMF, Tac, PP + IVIG | RTX, MMF, Tac, PP + IVIG, IA | RTX, MMF, Tac, PPP + IVIG |

| Number of sessions of PP/IA | 4 sessions of PP + IVIG | 6 sessions of PP + IVIG | 5 sessions of PP + IVIG | 7 sessions of PP + IVIG and 4 sessions of IA | 4 sessions of PP + IVIG |

| Induction Agent | ATG | ATG | ATG | ATG | Basiliximab |

| Immunosuppression | MTP | MTP | MTP | MTP | MTP |

T-FXM, T-Cell Flow cross-match; B-FXM, B-Cell Flow cross-match; DSA, Donor specific antibody; CDC, Complement dependent cytotoxicity; RTX, Rituximab; MMF, Mycophenolate mofetil; Tac, Tacrolimus; PP, Plasmapheresis; IVIG, Intravenous Immunoglobulin; IA, Immunoadsorption; MTP, MMF + Tacrolimus + Prednisolone

Desensitization protocol

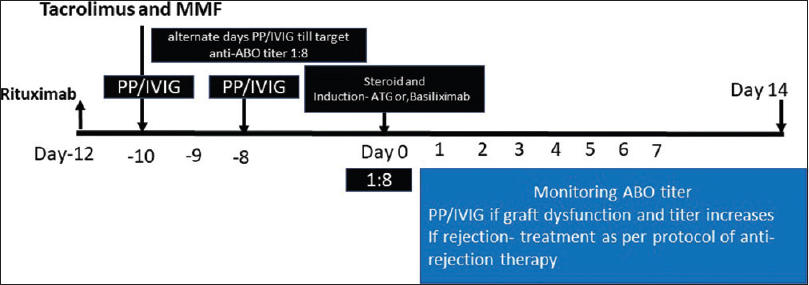

The desensitization protocol used in these patients are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2. All patients received rituximab 500 mg intravenously 12 days prior to transplantation as a part of desensitization. After 48 hours of rituximab injection, plasmapheresis (PP) (1 plasma volume removal with a replacement of 50% with plasma and 50% albumin) was performed on alternate days. Each PP was followed by IVIG infusion in a dose of 100 mg per kg of bodyweight to all recipients until the Anti-ABO antibody titers of 1:8 were achieved. Only the case 4 with Anti-ABO antibody titer of 1:512 required four sessions of Immunoadsorption with a low-molecular carbohydrate column containing A and B blood group antigens linked to a sepharose matrix (Glycosorb; Glycorex Transplantation, Lund, Sweden) to achieve the desired titer of 1: 8 before transplantation in addition to 7 sessions of plasmapheresis with IVIG infusion, as their titer used to bounce back. All patients received Tacrolimus (0.15 mg/kg body weight) and Mycophenolate-mofetil (1.5-2 g/day) from day-10 before RT. Four patients received three doses of rabbit ATG (1.5 mg per kg per dose for 3 doses on alternate day), and one patient received two doses of Basiliximab induction 20 mg each on day of RT prior to surgery and day-4 post RT. All patients received prophylaxis with Valganciclovir (450 mg once daily for six months); and Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (180/800 mg once daily for one year).

- Immunosuppression protocol used in the desensitization of the patients in the study

Post-transplant complications and follow-up

All patients had an uneventful immediate post-transplant course. Case 3 developed biopsy proven antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR) in the first week following RT which recovered with five sessions of plasmapheresis followed by IVIG infusion (400 mg/kg body weight). Case 4 developed combined rejection in the second post-transplant week, which responded to 3 doses of 500 mg methylprednisolone, and seven sessions of PP followed by IVIG infusion. None of the patients had a significant rebound of Anti ABO titer following transplant. Following discharge, patients were followed regularly.

Four episodes of E. coli UTI were noted in Case 3 within six months post RT and all episodes responded to the treatment. Case-5 had one episode of viral fever, which resolved itself. Case 1 had post-transplant hyperglycemia and transient leukopenia related to valganciclovir. Case 4 had thrombocytopenia related to MMF and resolved with a reduction of MMF dose. He later presented with altered sensorium. The magnetic resonsnce of head showed leptomeningeal enhancement and cerebrospinal fluid examination showed protein 80 mg/dl, glucose of 60 mg/dl, total leukocyte count 110 cells with lymphocyte predominance of 80 percent. The gene-xpert test turned to be positive and confirmed the diagnosis of tubercular meningitis. He had been started on anti-tuberculous therapy, however, he succumbed. This patient had received the highest degree of immunosuppression with seven sessions of PP and immunoadsorption, which predisposed him for the activation of infection.

Discussion

Our case series of repeat ABOi RT as a viable option showed an acceptable patient and graft survival on follow-up. Approximately 35% of the donors are excluded because of ABO incompatibility.[67] Even though ABOi RT, is now considered as an established modality of RT, the concerns and queries still exist with the varied approaches, risk assessment, rejections, infections, and success of repeat ABOi RT.[3456] Even the repeat ABOc RT recipients are also considered to be sensitized, and reportedly carries a higher risk of rejection and graft failure as compared to the first transplantation.[89] ABOi RT may further heighten the risk requiring more aggressive desensitization and, as a consequence, the attendant infectious complications. However, It is still considered to be a cost-effective option and provides a better quality of life.[10]

Each patient in the present case series received pre-transplant desensitization and immunosuppression as per the routine protocol for ABOi RT. All had mandatory CDC cross-match negative, and the Anti-ABO antibody titer was less than 8 at the time of RT. Only one patient had to be given Immunoadsorption in addition to PP for the attainment of desired titer. None of the patients had a post-transplant rebound of Anti ABO antibody titer. The patients who developed rejection responded to usual anti-rejection therapy. Infectious complications were not frequent or severe. In a situation of scarcity of organs in India with limited organized deceased donor program, fewer centers performing paired kidney, the repeat ABOi RT may be a small step forward to fill the gap to some extent.[11]

The United Nations Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry reported 1- and 5-year survival rates of 91% and 70%, respectively, for first renal transplants compared with 88% and 65% for repeated RT, primarily second grafts.[2] In a repeat RT study, Coupel et al. assessed the survival of cadaveric second kidney allografts and found a graft survival of 89% at one year, 76% at five years, and 53% at ten years.[8] A multivariate analysis of a French cohort showed that though second transplants had a higher risk of late graft failure, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of acute rejection or steroid-resistant acute rejection.[9] In our case series, two patients developed rejections; however, both responded to the therapy.

The past decade has seen the evolution of ABOi RT. It has been shown that ABOi RT has outcomes comparable with compatible RT in terms of safety and efficacy.[356] A study from Japan showed similar ten years patient and graft survival between ABOc and ABOi RT.[5] A protocol biopsy study reported a similar rate of rejection at 3 and 12 months post-transplantation.[6] Despite multiple success stories of ABOi RT in literature and our success story of repeat ABOi RT, there are multiple contradictory reports, as well. A recent meta-analysis comparing ABOi versus ABOc RT showed higher ABMR (10% vs 2%), lower one-year survival (96% vs 98%), higher non-viral infections (12% vs 6%) and infection associated death (49% vs 13%) in ABOi RT.[12] Another recent systematic review and meta-analysis showed ABOi was associated with significantly higher 1-year mortality and significantly lower death-censored graft survival. However, graft survival was equivalent to that of ABOc after five years and patient survival after eight years of RT.[13] Both studies suggest a higher requirement of immunosuppression and infection rate in ABOi transplantation.[1213] It is plausible that ABOi repeat RT is associated with heightened immunological risk.

In Meshari et al.[14] study of 124 patients, 39 ABOi and 85 histocompatible imcompatibility (HLAi), only 3 had both HLAi and ABOi, and 20% had re-transplantation. They showed 96% graft survival and 98% patients’ survival on 23 months follow-up after desensitization with risk stratification strategies. They observed an acute T cell mediated rejection rate of 12% and ABMR of 4%, out of which all rejection episodes reversed except one ABMR in the ABOi group. Pankhurst et al.[15] analyzed the UK National registry of 879 patients (522 HLAi and 357 ABOi); of them, only 55 were both ABOi and HLAi, which were included in HLAi group for data analysis. The 5-year transplant survival rates were 71% for HLAi and 83% for ABOi, compared with 88% for standard living donor transplants and 78% deceased donor transplants. Increased chance of transplant loss in HLAi was associated with an increasing number of DSA, and center performing the transplant, antibody level at the time of transplant. They have not separately analyzed the outcome of 55 patients who were both HLAi and ABOi.

In a Korean nationwide cohort study of 1964 transplantations, 31 were both ABO and HLAi and only 19% re-transplantation. The authors revealed that the patient survival rate was lower than the control group, and desensitization was found to be an independent risk factor for mortality on follow-up. The incidence of biopsy-proven acute rejection in the combined ABOi and HLAi group was higher than the control group. Still, the allograft survival remained the same, and the rejections were mainly late. HLA incompatibility, irrespective of ABOi, was found to be a significant risk factor for biopsy-proven acute rejection.[16]

One study[17] looked at outcomes of RT recipients transplanted across simultaneous ABOi and HLAi compared to recipients with ABOi or HLAi alone. In the combined ABOi and HLAi group, 57% of the recipients were re-transplanted, out of which less than half had received 2 or more transplants. One-year patient and death censored graft survival was 96% and 93%, respectively. The patient and death censored graft survival in combined ABOi and HLAi group was 93% and 82%; only HLAi group was 88% and 87%; only the ABOi group was 85% and 79%, respectively after 36 months follow-up. The study showed the short-to-medium term safety and efficacy of transplanting patients across simultaneous ABOi- and HLAi barriers in a relatively larger number of patients. In a retrospective study, Barnes et al.[18] showed that third and fourth kidney transplants could be performed safely with similar outcomes to first and second transplantation. However, this study did not include ABOi RT. A case of ABO Incompatible simultaneous liver-kidney Transplant with positive cross-match has been reported.[1920]

It has been observed that desensitization strategies varied widely in each study, and outcomes also varied depending on the center's experience. The careful selection of patients with the absence of DSA could have probably contributed to the excellent graft survival seen in our series. Only one patient had DSA in our series. No additional immunosuppression was utilized than that needed in a routine ABOi first renal transplant and therefore the fewer infectious episodes were seen in our series. The present case series showed that ABOi repeat RT might be possible in highly sensitized patients. A case report of third successful transplantation has recently been reported from India,[21] which was performed much later than third transplant patients in our case series. Our third transplant recipient was different in the sense that this patient had hyperacute rejection during the second transplant.

The main limitation of our observation is the small sample size, being limited to a single-center, and the variable duration of follow up. Further multicentric studies are a necessity to understand the course and prognosis of patients undergoing ABOi repeat RT. A good pre-transplant cross-matching, sensitive HLA matching, screening for DSA, and the utilization of potent immunosuppression are undeniably the crux of managing patients undergoing ABOi- repeat RT.

Conclusion

Live related ABOi repeat RT is a viable option for patients with a previously failed graft. Careful pretransplant testing and the utilization of potent immunosuppression with adequate ABO desensitization enables to perform repeat transplant with a reasonably good graft and patient survival.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Outcome of second kidney transplant: A single center experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2013;24:696.

- [Google Scholar]

- Current progress in ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2015;34:170-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- ABO incompatible living donor kidney transplantation in Korea: Highly uniform protocols and good medium-term outcome. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:875-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation as a renal replacement therapy—A single low-volume center experience in Japan. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0208638.

- [Google Scholar]

- Histological analysis in ABO-compatible and ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation by performance of 3- and 12-month protocol biopsies. Transplantation. 2017;101:1416-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- ABO-incompatible renal transplantation in developing world-crossing the immunological (and mental) barrier. Indian J Nephrol. 2016;26:113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ten-year survival of second kidney transplants: Impact of immunologic factors and renal function at 12 months. Kidney Int. 2003;64:674-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Poor long term outcome in second kidney transplantation: A delayed event. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47915.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cost-effectiveness of repeat medical procedures: Kidney transplantation as an example. Med Decis Making. 1997;17:363-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney paired donation and optimizing the use of live donor organs. JAMA. 2005;293:1883-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcomes after ABO-incompatible renal transplantation. Lancet. 2019;394:1988-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of desensitization in human leukocyte antigen- and ABO-incompatible living donor kidney transplantation: A single-center experience in more than 100 patients. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:1423-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The UK national registry of ABO and HLA antibody incompatible renal transplantation: Pretransplant factors associated with outcome in 879 transplants. Transplant Direct. 2017;3:e181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcomes of ABO- and HLA-incompatible kidney transplantation: A nationwide cohort study. Transpl Int. 2017;30:1215-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney transplant across simultaneous ABO/HLA incompatible barriers is similar to either ABO or HLA incompatible transplant for safety and efficacy. Transplantation. 2012;10S:178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kidney re-transplantation from HLA-incompatible living donors: A single center study of third and fourth transplants. Clin Transplant. 2017;31:e13104.

- [Google Scholar]

- ABO incompatible simultaneous liver-kidney transplant with positive crossmatch. A case report [Abstract] 2015. Am J Transplant. 15 https://atcmeetingabstracts.com/abstract/ abo-incompatible-simultaneous-liver-kidney-transplant-with-posit ive-crossmatch-a-case-report/

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful simultaneous liver-kidney transplantation in the presence of multiple high-titered class I and II antidonor HLA antibodies. Transplant Direct. 2016;2:e121.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful third kidney transplant after desensitization for combined Human leucocyte antigen (HLA) and ABO incompatibility: A case report and review of literature. Am J Case Rep. 2019;20:285-9.

- [Google Scholar]