Translate this page into:

Color-Doppler sonographic tissue perfusion measurements reveal significantly diminished renal cortical perfusion in kidneys with vesicoureteral reflux

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

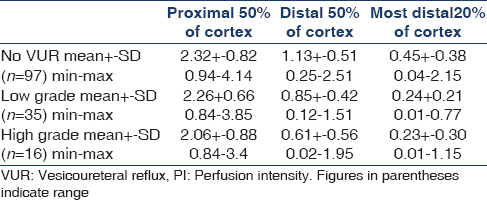

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and its sequelae may lead to reduced renal perfusion and loss of renal function. Methods to describe and monitor tissue perfusion are needed. We investigated dynamic tissue perfusion measurement (DTPM) with the PixelFlux-software to measure microvascular changes in the renal cortex in 35 children with VUR and 28 healthy children. DTPM of defined horizontal slices of the renal cortex was carried out. A kidney was assigned to the “low grade reflux”-group if the reflux grade of the voiding cystourethrogram was 1 to 3 and to the “high grade reflux”-group if the reflux grade was 4 to 5. Kidneys with VUR showed a significantly reduced cortical perfusion. Compared to healthy kidneys, this decline reached in low and high grade refluxes within the proximal 50% of the cortex: 3% and 12 %, in the distal 50% of the cortex: 21% and 44 % and in the most distal 20 % of the cortex 41% and 44%. DTPM reveals a perfusion loss in kidneys depending on the degree of VUR, which is most pronounced in the peripheral cortex. Thus, DTPM offers the tool to evaluate microvascular perfusion, to help planning treatment decisions in children with VUR.

Keywords

Children

cortical perfusion measurement

Doppler ultrasound

vesico-ureteral reflux

Introduction

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is an important cause of renal function decline loss leading to end stage renal failure.[123456] Controversy exists about the mechanism of renal function loss. There is evidence for a disturbed renal development in children with VUR as well as an increased risk for renal infection and subsequent scarring. Both mechanisms can be severe enough to destroy the normal architecture by obliterating the renal microvasculature. Dynamic tissue perfusion measurement (DTPM) is a new method to measure tissue microvascular perfusion by means of the PixelFlux-software (PXFX), and standardized color-Doppler sonographic videos. It has proven potential to measure perfusion in microvessels in kidneys, renal transplants, intestines, lymph nodes, thyroid, cancer of the neck and ovaries and muscles.

The aim of this study was to measure the changes of renal microperfusion in the layers of the renal cortex in children with VUR compared with healthy children. This study was approved by the Institute Ethical Committee.

Patients and Methods

The group of healthy children consisted of 28 (11 girls, 17 boys) from 1 to 16 (mean 9.59) years of age. All of them were healthy and had no history of renal disease, a normal abdominal ultrasound and a normal renal volume.

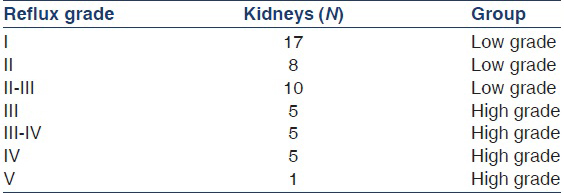

The group of children with VUR consisted of 35 (25 girls, 10 boys) from 0 to 12 years of age (mean 4.07 years). In 16 a bilateral reflux was diagnosed by means of VCU, and in the remaining 19, a unilateral reflux was found. Altogether 51 kidneys were refluxive and were classified according to their reflux grade as low high grade [Table 1].

All children got a color-Doppler sonographic examination under standardized conditions. In those with reflux this exam was within 6 months before or after the VCU in a situation where no acute renal disease was found.

For VCU, the urethra was catheterized with a flexible catheter covered with an anesthetic lubricant and the urinary bladder was slowly filled with contrast medium. When instillation was finished an X-ray of the bladder was performed. After voiding, a second X-ray image of the ureters and kidneys was taken if the fluoroscopy demonstrated a reflux. The reflux grade was determined according to the classification of the International Reflux Study Group.[7]

All ultrasound examinations were done with the patient in prone position by the same investigator (TS). An ACUSON Sequoia 512 ultrasound machine (Acuson, Mountainview, CA, USA) was used equipped with a curved array transducer offering a frequency range from 4 to 1 MHz in B-mode. The B-mode frequency was 4 MHz with a 7 MHz color-Doppler frequency.

The color-Doppler examination was performed with a fixed algorithm and predefined machine settings (fixed preset). Standardized recordings of color-Doppler sonographic videos in DICOM-format were then transferred to a personal computer where DTPM was carried out with the PXFX (PixelFlux-software, Chameleon-Software GmbH, Münster, Germany).[8]

The central part of the kidney in a longitudinal section was enlarged so that the central segment and parts of its neighboring segments were to be seen clearly and as large as possible.

The central interlobar artery was running straight toward the transducer with its arcuate arteries branching symmetrically to both sides. The outer surface of the kidney could be discriminated from the surrounding fat (high echogenicity) by a discrete demarcation border. With a fixed color-Doppler sonographic preset (color-Doppler frequency 7 MHz, B-mode frequency 4 MHz, color gain 50, space-time resolution preference 1, edge - 1, persistence 2, postprocessing V, sample volume size 1, wall filter 3) a video sequence of 2 s was recorded in breath holding technique. Each video contained at least one full heart cycle.

All videos were automatically calibrated for distances and color hues by the PXFX.[8] The region of interest (ROI) was defined as a parallelogram encompassing one full cortical segment from the outer borders of the medullary pyramids (MP) to the renal capsule and laterally from the center of one MP to the center of the neighboring MP. Within the ROI horizontal slices were separated, which encompassed the proximal 20% of the ROI (p20), the proximal 50% (p50), the distal 50% (d50) and the most distally 20% (d20) [Figure 1]. Care was taken to observe the watersheds of blood flow between two neighboring cortical segments as lateral borders of the ROI. Perfusion measurement was carried out automatically by PXFX.

- Delineation of the position of subsequent layers for dynamic tissue perfusion measurement within the renal cortex (upper part) and example of perfusion measurement with the PixelFlux-software within the outer 50% of the renal cortex (lower part). A false color map of perfusion distribution within the region and a diagram of distribution of perfusion intensities can be seen. MP - medullary pyramid

Perfusion intensity (PI) was calculated as:

PI (cm/s) = v (cm/s) × A (cm²)/A ROI (cm²)

v: Mean velocity value of all pixels of the ROI at a certain time; A: Mean area occupied by all pixels of the ROI at a certain time; A ROI: Area of the ROI.

All measurements of v and A were done image by image of the entire video. PXFX then recognized complete heart cycles within the video and calculated mean values for v and A for complete heart cycles only. PI thus combines all relevant data that determine blood flow intensity per heart cycle.

For comparisons between groups the Mann–Whitney U-test was applied. Correlations were evaluated by the Spearman rank correlation or Pearson's correlation. p < 5% were regarded as statistically significant.

Results

The number of cases with different grades of reflux are: I: 17, II: 8, II-III: 10, III: 5, III-IV: 5, IV: 5 and V: 1. Significant differences in renal cortical perfusion were found spared between groups [Table 2 and Figure 2]. The differences were most prominent in the outer 20% of the renal cortex (region d20). A significant decline of perfusion could already be demonstrated within the distal 50% [Figure 3]. A clear distinction could be made between low and high grades of reflux. The decline of perfusion intensity from the proximal to the distal cortex (p50 - d50 -d20) was in healthy kidneys 100% - 46% - 18%, in low grade VUR 100% - 38% - 11% and in high grade VUR 100% - 30% - 11%)

- Boxplots of perfusion intensities within the d20 layer in healthy kidneys, affected kidneys free of reflux and refluxive kidneys

- Boxplots of perfusion intensities within the d50 layer in healthy kidneys, and two groups of refluxive kidneys – with low grade and high grade refluxes

Discussion

Vesico-ureteral reflux is associated with renal scars and perfusion deficits.[9] Scarring is the cornerstone of renal function loss and its prevention thus a major goal in the care of children with VUR.[21011] Scintigraphy and ultrasound can detect circumscribed renal scars but these may be late consequences of bacterial infections or long-standing high grade (grade 4–5) VUR. Renal dysplasia was found to be associated with VUR in antenatally detected VUR but no postnatal scarring was found in these children in follow-up, whereas neonatal urinary tract infection superimposed on VUR led to renal scars in 19% of the kidneys.[12]

Scarring is the consequence of local ischemia and may be focal but more often fibrosis is delicately dispersed throughout the renal parenchyma and evades early recognition. Only late parenchymal destruction is seen in ultrasound B-mode images as increasing echogenicity, shrinking of the kidney and loss of intrarenal tissue differentiation. Nothing can be said concerning renal perfusion with B-mode ultrasound. Renal perfusion measurement is feasible with scintigraphic techniques, but their use is restricted due to lower availability and technical limitations (supply of the I-131-hippuran, radiation exposure, need to immobilize younger children). Spatial resolution is low in all scintigraphic techniques compared to ultrasound imaging. Color-Doppler ultrasound offers high spatial resolution of renal parenchyma and high time resolution of perfusion signals. DTPM has demonstrated its capacity to monitor subtle changes of renal parenchyma.[1314151617181920]

We demonstrated a significant decline of renal cortical perfusion with increasing degrees of VUR with the new technique of DTPM. Our results are in contrast to experimental perfusion measurements using radio labeled microspheres in pigs where no relevant perfusion changes could be demonstrated immediately after operation-induced VUR.[21] Nevertheless, the same authors found in the same model clear perfusion changes preferentially in the upper and lower pole region.[22] In another porcine model renal function as well as maintenance of renal perfusion was disturbed after 3–4 months after experimental induction of reflux.[23] Porcine kidneys are prone to intrarenal reflux due to the fusion of MPs in the upper and lower poles with gaping collecting ducts[242526] and differ from human kidneys in this aspect.[27]

No direct measurements of renal perfusion could be retrieved in a PubMed search with the items “VUR” and “perfusion” or “blood flow” except the paper from Greenfield et al. and Lewis et al. and their group.[2122] Frauscher et al. found a significantly increased vascular resistance with color-Doppler sonographic measurements and a good correlation to scintigraphy in 46 children with VUR.[28] But resistance index measurements give no clue to tissue perfusion since they do not refer to true flow velocities and perfused area inside a ROI. This limitation is now overcome by DTPM. It was shown in a recent study that DTPM can reveal very early microvascular damage in renal parenchyma in children with type 1 diabetes before the onset of a microalbuminuria.[29]

We could demonstrate with the present investigation that this technique can already detect a perfusion decline in low grade VUR and is able to demonstrate severe microvascular impairment in kidneys with a high grade reflux. Thus, it offers the opportunity to follow-up patients in order to respond to the beginning of this functional deterioration with kidney preserving therapies.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Thomas Scholbach co-developed the PixelFlux-software, applied in this work to measure cortical perfusion, and is a shareholder of Chameleon Software GmbH.

References

- Outcome of kidneys in patients treated for vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) during childhood. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2491-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vesicoureteral reflux associated renal damage: Congenital reflux nephropathy and acquired renal scarring. J Urol. 2010;184:265-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Long-term followup of infants with gross vesicoureteral reflux. J Urol. 1992;148:1709-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Primary vesicoureteral reflux with renal failure in adults. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 1991;111:1721-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vesicoureteral reflux in the adult. II. Nephropathy, hypertension and stones. J Urol. 1983;130:41-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal outcome in patients with congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract. Kidney Int. 2009;76:528-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- International system of radiographic grading of vesicoureteric reflux. International Reflux Study in Children. Pediatr Radiol. 1985;15:105-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chameleon-Software, PixelFlux. 2009. Available from: http://www.chameleon-software.de

- [Google Scholar]

- High grade primary vesicoureteral reflux in boys: Long-term results of a prospective cohort study. J Urol. 2010;184:1598-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal scarring in familial vesicoureteral reflux: Is prevention possible? J Urol. 2006;176:1842-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal parenchymal damage in intermediate and high grade infantile vesicoureteral reflux. J Urol. 2008;180:1635-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Risk of renal scarring in vesicoureteral reflux detected either antenatally or during the neonatal period. Urology. 2003;61:1238-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new method of color Doppler perfusion measurement via dynamic sonographic signal quantification in renal parenchyma. Nephron Physiol. 2004;96:p99-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dynamic tissue perfusion measurement: A novel tool in follow-up of renal transplants. Transplantation. 2005;79:1711-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tissue pulsatility index: A new parameter to evaluate renal transplant perfusion. Transplantation. 2006;81:751-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Correlation of histopathologic and dynamic tissue perfusion measurement findings in transplanted kidneys. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dynamic tissue perfusion measurement: A new tool for characterizing renal perfusion in renal cell carcinoma patients. Urol Int. 2013;90:87-94.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-invasive assessment of renal allograft fibrosis by dynamic sonographic tissue perfusion measurement. Acta Radiol. 2011;52:920-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Donor effect on cortical perfusion intensity in renal allograft recipients: A paired kidney analysis. Am J Nephrol. 2011;33:530-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of cardiovascular organ damage on cortical renal perfusion in patients with chronic renal failure. Biomed Res Int 2013 2013 137868

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal blood flow measurements using radioactive microspheres in a porcine model with unilateral vesicoureteral reflux. J Urol. 1991;146:649-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regional renal blood flow measurements using radioactive microspheres in a chronic porcine model with unilateral vesicoureteral reflux. J Urol. 1995;154:816-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal blood flow and function in vesico-ureteric reflux. An experimental study in the pig. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1975;28(suppl):71-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal papillary morphology and intrarenal reflux in the young pig. Urol Res. 1975;3:105-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The relation of the shape of renal papillae and of collecting duct openings to intrarenal reflux. Br J Urol. 1977;49:345-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of renal resistance index in children with vesico-ureteral reflux. Ultraschall Med. 1999;20:93-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Color Doppler sonographic dynamic tissue perfusion measurement demonstrates significantly reduced cortical perfusion in children with diabetes mellitus type 1 without microalbuminuria and apparently healthy kidneys. Ultraschall Med. 2014;35:445-50.

- [Google Scholar]