Translate this page into:

Cytomegalovirus-Related Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis after Renal Transplantation

Address for correspondence: Dr. Urmila Anandh, Department of Nephrology, Yashoda Hospitals, Secunderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: uanandh@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Dear Sir,

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare multifaceted disease when seen in adults in the context of autoimmune diseases, infections, and malignancies. It is often missed because of its subtle symptomatology and lack of clinical suspicion. Sporadic and rare cases of HLH are reported in organ transplantation.[1] We report a case of renal allograft recipient who had persistent lymphopenia secondary to cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection which finally evolved into HLH.

A 49-year-old lady who underwent a renal transplant (native kidney disease – IgA nephropathy) a year ago was back referred to us with history of electrolyte disturbances and allograft dysfunction. She had been well with stable allograft function (last follow up serum creatinine 1.09 mg/dl) after transplantation. Two weeks before the referral, she had presented to her initial transplant nephrologist with seizures and fever. Evaluation at our center showed severe dehydration, hyponatremia (109 meq/mL), hypocalcemia (corrected calcium 6.2 mg/dL), hypophosphatemia (1.8 mg/dL), and profound hypomagnesemia (0.8 mg/dL). As the clinical assessment of the patient revealed severe dehydration, a diagnosis of acute symptomatic hypovolemic hyponatremia was considered, and the patient was treated with 3% saline. Other electrolyte deficits were appropriately replaced. Her fever evaluation revealed the presence of CMV viremia (quantitative PCR showed more than 2.9 million IU/mL). A EBV PCR test was not done due to financial constraints. She was treated with intravenous ganciclovir (5 mg/kg twice a day for 2 weeks). The electrolyte abnormalities were thought to be tacrolimus-mediated proximal tubular dysfunction, and tacrolimus was replaced with everolimus (0.75 mg once a day and later increased to twice a day.). Mycophenolate sodium was also discontinued because of leucopenia. An allograft biopsy did not reveal significant abnormality. There was no evidence of acute tubular injury, thrombotic microangiopathic changes, or chronicity. Staining for CMV was not done. Her fever subsided on the fourth day and she was discharged on iv ganciclovir. At discharge her hemogram was normal. On follow up after a week, her quantitative PCR revealed the presence of CMV viremia (56,000 IU/mL) and was told to continue iv ganciclovir for another week. Her hemogram at follow up showed normal leucocyte (7640/μL) and platelet counts (156000/μL).

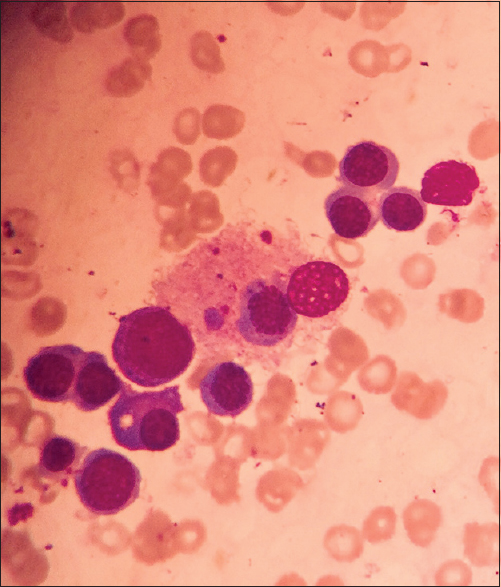

A week later, she presented with symptoms of giddiness, dehydration, and tingling of limbs. Her investigations revealed allograft dysfunction (creatinine 2.2 mg/dL), hyponatremia (serum sodium 129 meq/L), and pancytopenia (Hemoglobin 9.6 g/dl, total leucocyte count 2030/μL Platelets-75 thousand/μL). There was splenomegaly on the ultrasound evaluation of her abdomen. Everolimus was stopped and her steroids were increased. Hypovolemia was corrected with intravenous fluids. The hyponatremia and allograft dysfunction improved; however, her leucocyte count dropped to 700/μL and she received G- CSF injections (300 μg s.c for 3 days). Her ganciclovir dose was also interrupted (she had already received more than 20 days of the injection). She underwent a bone marrow aspiration and biopsy as her counts did not improve. The bone marrow revealed significant hemophagocytosis [Figure 1]. Further evaluation revealed a high ferritin (5670 ng/ml) and low fibrinogen (104 mg/dl) levels. A presumptive diagnosis of HLH was made. The CMV infection was considered to be responsible for HLH and ganciclovir was restarted with intermittent G-CSF injections. She received the therapy for a total of another 2 weeks. She also received weekly intravenous immunoglobulin (100 mg/kg) for 4 weeks. On follow up after 2 weeks, her repeat CMV PCR was negative. Her leucocyte count (10,100/μl) and platelets (240,000/μL) also normalized. Her creatinine stabilized at 1.5 mg/dL and ferritin was 859 ng/mL on follow up. She is currently on everolimus (0.75 mg twice a day), mycophenolate sodium (360 mg three tablets a day), and steroids (5 mg/day).

- Bone marrow aspirate showing a histiocyte with engulfed erythroid precursor and platelets

In a review on HLH in transplant patients, the authors mention that patients usually present with high fever and constitutional symptoms. Hepatosplenomegaly may be absent. Hyponatremia is seen in about 60% of patients.[2] Our patient satisfied many criteria for the diagnosis of HLH.[3] The clinical diagnosis was not considered initially as the cytopenia was attributed to drug toxicity and CMV infection. It was only when cytopenia worsened despite withdrawal of the offending drugs that the clinical suspicion of HLH was considered, which was subsequently confirmed by a bone marrow examination.

CMV infection has been associated with the development of HLH and the diagnosis is often missed because of overlapping signs and symptoms of both the clinical entities.[4] A late onset CMV infection leading to HLH can be fatal unless treated early. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment including IVIg[5] of this potentially fatal disease led to a favorable outcome in our patient. The current recommendation of viral infections associated HLH suggest the use of virostatics and IVIg. Even though there is difference in adult and pediatric HLH, successful treatment in adults is also becoming common if the cause is identified and treated adequately.[6]

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Groupe cooperatif de transplantation d'lle de France. Hemophagocytic syndrome in renal transplant recipients; report of 17 cases and review of literature. Transplantation. 2004;77:238-243.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hemophagocytic syndrome- A life-threatening complication of renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:2623-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnostic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Semin Oncol. 1991;18:29-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hemophagocytic syndrome in kidney transplant recipients: Report of four cases from a single center. Acta Haematol. 2006;116:108-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment of cytomegalovirus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome by intravenous immunoglobulins. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:159-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019;133:2465-77.

- [Google Scholar]