Translate this page into:

Endogenous Endophthalmitis in the Setting of Kidney Disease: A Case Series

Corresponding author: Ramprasad Ramalingam, Department of Nephrology, NU Hospitals, Bangalore, India. E-mail: dr.ramprasad@nuhospitals.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Santanaraman R, Ramalingam R, Rangarajan D, Patro KC, Elenjickal NJ. Endogenous Endophthalmitis in the Setting of Kidney Disease: A Case Series. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:652-4. doi: 10.25259/IJN_271_2024

Abstract

Blood stream infections (BSI) are common in patients with kidney disease. Metastatic foci of infections are one of the known complications of BSI. Endophthalmitis which is defined as infection and inflammation of the inner coats of the eye ball and intraocular fluids (aqueous and vitreous), is one such focus. We discuss the clinical profile of five patients who had endogenous endophthalmitis in the setting of kidney disease and their management and outcome. All five had diabetes mellitus; the source was central venous catheter in two and urinary tract infection in two. Microbial cause was Staphylococcus aureus in two, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in one, Klebsiella pneumoniae in one and Candida albicans in one. All five required dialysis. Recovery of vision was poor with partial recovery only in two patients. A vision-threatening emergency, this condition requires early identification and management for better recovery of vision.

Keywords

Endophthalmitis

Kidney Disease

Sepsis

Vitritis

Introduction

Endophthalmitis, a dreaded ophthalmological emergency, is the intraocular infection of the inner coats of the eyeball associated with diffuse vitreous inflammation.1 Exogenous endophthalmitis can result from trauma, keratitis, or postsurgery or intravitreal injection of medications.2 Endogenous Endophthalmitis (EE) occurs in only 2–8% of all cases of endophthalmitis.1 EE is a systemic complication of hematogenous spread of infectious pathogens from foci of infection elsewhere. The most common systemic risk factors include diabetes mellitus (DM), immunosuppression, long-term corticosteroid use, solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, malignancies, chemotherapy, chronic alcoholism, intravenous infusion, indwelling catheters, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, drug abuse, etc.3

Case Series

We present details of five patients with kidney disease who developed EE between 2015 and 2023 in Table 1. All five had DM; three were females. The endogenous infection occurred in the setting of catheter related blood stream infection in two, urosepsis in two, and subcutaneous infection in one. Bilateral involvement occurred in two. The cause of blood stream infection (BSI) was bacterial in four (Staphylococcus aureus in two, Pseudomonas aeruginosa in one, and Klebsiella pneumoniae in one) and fungal in one. The same organism could be isolated from ocular fluid in two out of the four patients who had undergone ocular fluid sample collection. Overall, the outcome is poor in these patients; two had expired within a month of the infection; only two are on follow-up at the time of this write-up. Recovery of vision was worse with partial recovery only in two. Ethical approval was obtained.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 40 | 51 | 71 | 34 | 70 |

| Gender | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female |

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Eye involvement | Right eye | Left eye | Both eyes | Both eyes | Right eye |

| Kidney disease |

Renal Transplant recipient (10 years) Return to dialysis after graft loss Vascular access–CVC |

CKD 5D Vascular access–CVC |

Infection-related glomerulonephritis Dialysis requiring AKI managed with short-course steroid therapy |

Pyelonephritis Dialysis requiring AKI Managed with antibiotics and bilateral ureteric stenting |

CKD 5D Vascular access–tunneled CVC |

| Septic focus | Skin and subcutaneous infection–Abscess over IV cannula site (no CVC for 10 days prior to this episode) | CVC (Catheter days 81)–removed promptly | Urinary tract | Urinary tract | CVC (Catheter days: 233) – removed promptly |

| Blood culture | Staphylococcus aureus | Staphylococcus aureus | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Candida albicans | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Urine culture | - | - | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Candida albicans | - |

| Aqueous and vitreous culture | Staphylococcus aureus | - | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Sterile | Sterile |

| Systemic antibiotic | Vancomycin | Dicloxacillin followed by Cefazolin | Piperacillin Tazobactum followed by Meropenem | Caspofungin followed by Fluconazole | Ceftazidime and oral Ciprofloxacin |

| Intraocular antibiotic | Vancomycin and Amikacin | Vancomycin and Amikacin | Imipenem and Amikacin | Vancomycin, Voriconazole and Amphotericin B | Vancomycin and Amikacin |

| Vitrectomy |

Not done Lateral canthotomy was done to reduce intraocular pressure |

Done | Right eye vitrectomy and left eye evisceration were advised. Patient was transferred to multispecialty care where he expired | Done | Not done |

| Vision outcome | Right eye–perception of light | Left eye–no vision | Right eye–perception of light; left eye–- no vision | Left eye: 6/24 unaided; 6/12 with glasses Right eye: counting finger at 1 meter | Right eye: counting finger at 1 meter |

| Patient survival | Lost to follow-up | Alive | Expired | Alive | Expired |

CVC: Central venous catheter, CKD: Chronic kidney disease, AKI: Acute kidney injury

Discussion

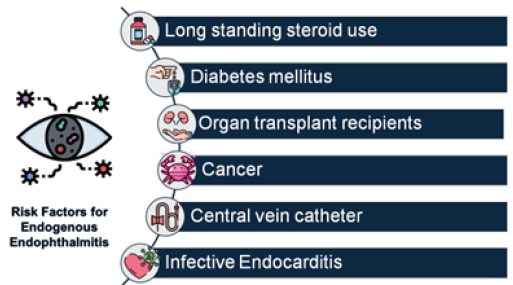

Patients with renal dysfunction are more vulnerable to infections for several reasons: structural and functional abnormalities of urinary tract, immunocompromised state secondary to DM, immunosuppressive therapy for glomerular and interstitial diseases and for renal transplantation, and dialysis access and dialysis procedure can predispose patients with kidney disease to infections. Hematogenous spread of infectious agents in the setting of severe sepsis and the occurrence of metastatic infection is more likely in these patients. EE is one such rare metastatic focus that often leads to permanent vision loss [Figure 1].

- Risk factors for Endogenous Endophthalmitis.

Microorganisms circulate in the bloodstream from a distant focus of infection to the inner eye as septic emboli through posterior segment vessels and cause EE. These septic emboli then act as focus of infection that spreads to adjacent tissues by breaking the blood retinal barrier. The most important diagnostic feature is vitreous involvement.

The pathogens causing endophthalmitis most frequently are gram-positive bacteria (85%) including coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Staphylococcus aureus; gram-negative bacteria, especially Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas, are the causes in 10% and fungal organisms in 4–6%.4

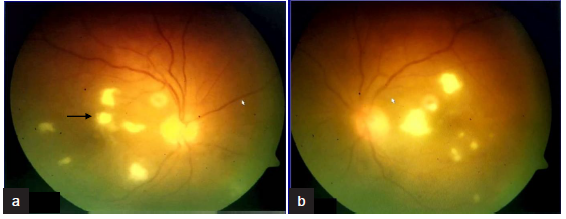

Endophthalmitis presents with painful red eye, photophobia, floaters or reduced vision. Bilateral involvement can happen in 19–33% of cases.5 Ocular examination shows reduced visual acuity, conjunctival injection, corneal edema, hypopyon, anterior chamber cells, iritis and vitritis.5 A key diagnostic finding is the presence of white infiltrate originating in the choroid erupting into the vitreous cavity [Figure 2]. The fundus may be obscured because of vitreous haze or vitritis. If the posterior segment cannot be visualized, B-scan ultrasound can help to identify vitritis or chorioretinal infiltrates.6 Vitreous fluid culture has high yield of causative organism. PCR test is useful in culture-negative cases to detect both bacteria and fungi. Beta glucan assay may be useful in suspected fungal cases and has high negative predictive value (98%).6

- Fundus findings of patient 4 with fungal endophthalmitis (a) Right eye (b) Left eye. The fundus findings showing multifocal white retinitis lesions in both eyes with foveal involvement in right eye (black arrow in a).

Systemic as well as intraocular antibiotic therapy with appropriate antimicrobial agent is warranted; the retinal blood barrier prevents antibiotic from reaching intraocular layers7 though inflammation allows for some antibiotic penetration. Vitrectomy with intraocular antibiotics has better visual outcomes and is less likely to require evisceration or enucleation when compared with intravitreal antibiotic alone.6 Judicious and early use of systemic and intraocular steroid therapy may help in better visual outcomes.

Endophthalmitis complicating dialysis access infection is not common and is infrequently reported.7,8 All the three patients in these two reports had DM; central venous catheter was the source. Organism responsible was Staphylococcus aureus in two and Staphylococcus hemolyticus in one. Two had undergone evisceration; vision improved with intraocular antibiotic in the other patient.7,8

Patients with septicemia in the setting of kidney disease are at high risk for EE in view of the disease burden combined with multiple comorbidities. EE, a sight-threatening emergency, requires high degree of suspicion for early referral to a vitreoretinal surgeon and early initiation of broad spectrum antibiotic essential for better outcomes.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Endogenous endophthalmitis: Diagnosis, management, and prognosis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2015;5:32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Endogenous endophthalmitis: 10 year experience at a tertiary referral centre. Eye (Lond). 2011;25:66-72.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Microbiology spectrum and antibiotic sensitivity in endophthalmitis: A 25 year review. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1634-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endophthalmitis: State of art. Clin ophthalmol. 2015;9:95-108.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Endophthalmitis complicating dialysis access infection. Kidney int. 2017;92:270.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endophthalmitis: A rare but devastating metastatic bacterial complication of hemodialysis catheter-related sepsis. Ren Fail.. 2012;34:119-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]