Translate this page into:

Obesity and graft dysfunction among kidney transplant recipients: Increased risk for atherosclerosis

Address for correspondence: Dr. Aminu S. Muhammad, Department of Medicine, Yariman Bakura Specialist Hospital, PMB 1010, Gusau, Zamfara State, Nigeria. E-mail: aminuskj@yahoo.com

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Weight gain after kidney transplant is common, and may be related to graft dysfunction and high cardiovascular risk. We investigated the prevalence of obesity and evaluated the relationship between obesity and graft dysfunction in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs). All patients who received kidney transplant at the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH) between January 2005 and December 2009 were recruited. Information on demographics, clinical characteristics and post-transplant care were documented. All patients underwent transthoracic echocardiography and carotid Doppler ultrasound for the assessment of cardiac status and carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT), respectively. Inferential and modelling statistics were applied. One hundred KTRs were recruited, of which 63 were males. The mean age was 42.2 ± 12.42 years with a range of 19-70 years. The mean body mass index and waist circumference of the recipients were 26.4 ± 4.81 kg/m2 and 90.73 ± 14.76 cm, respectively. Twenty-nine patients (29%) were obese; of these, 24 (82.8%) had moderate obesity, 4 (13.8%) had severe obesity, and 1 (3.4%) had morbid obesity. Graft dysfunction was present in 52%. Obese patients were older (P < 0.0001), had graft dysfunction (P = 0.03), higher mean arterial blood pressure (P = 0.022), total cholesterol (P = 0.019), triglycerides (P < 0.0001), left ventricular mass index (P = 0.035) and cIMT (P = 0.036). Logistic regression showed obesity to be independently associated with graft dysfunction (P = 0.033). Obesity after kidney transplantation is common and is associated with graft dysfunction and markers of atherosclerosis.

Keywords

Graft dysfunction

kidney transplant recipients

obesity

Introduction

Weight gain after transplantation is common and may be related to improved appetite with reversal of uremia, relatively high steroid doses in the peri-transplant period and physical inactivity.[1] High body mass index (BMI) correlates with diabetes, high blood pressure (BP) and plasma lipids as well as proteinuria and graft dysfunction.[2] Bardonnaud et al., found obese kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) to be older, diabetic and more likely to have had delayed graft function.[3] Several studies showed similar graft and patients' outcomes between obese and normal weight KTRs.[234]

We investigated the prevalence of obesity and evaluated relationship between obesity and graft dysfunction in KTRs at the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH).

Materials and Methods

Enrollment commenced in June 2012 and was completed in October 2012 in this cross-sectional study. Using a structured interview form, information on age, gender, physical activity, tobacco use and the number of transplants was collected. Physical activity was evaluated by asking patients if they engaged in regular exercises such as brisk walking, jogging, swimming or bicycling. Patients were classified into three groups based on their smoking history. They were categorized as smokers if they were current smokers, former smokers if they stopped smoking for at least 6 months and nonsmokers if they had never smoked. The types of immunosuppression, use of BP medications and biopsy-proven rejection were all recorded. Height and weight were measured with the Detecto scale (New York), and BMI was calculated as the ratio of weight to height squared. Waist circumference was measured using a tape rule, and the point of measurement was the anterior superior iliac spine.[4] Graft dysfunction was defined as estimated GFR of <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 based on the modification of diet in renal disease formula. Obesity was defined as BMI of ≥30 kg/m2.

Blood pressure

Blood pressure was recorded at the time of clinic visit using an Accoson mercury sphygmomanometer in the sitting position. BP average of four clinic visits was taken as the patient's actual BP (averaged over 12 months). Pulse pressure was calculated as the difference between the systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), whereas mean arterial pressure (MAP) was the sum of DBP and one-third of the pulse pressure.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was done at the Cardiology Unit of CMJAH using the Philips iE33 machine equipped with a S5-1 1-5 MHz transducer, allowing for M-mode, two-dimensional and color Doppler measurements (Philips Corporation, USA).

Carotid intima-media thickness

Carotid artery intima media thickness (IMT) was measured using high-resolution B-mode ultrasonography with an L3-11 MHz linear array transducer (Philips Corporation, USA). Patients were examined in the supine position with the neck hyper-extended, and the head turned 45° from the side being examined. Reference point for the measurement of IMT was the beginning of the dilatation of the carotid bulb. IMT was taken as the distance from the leading edge of the first echogenic line to the leading edge of the second echogenic line.

Measurements were taken on the longitudinal views of the far walls of the common carotid artery 1 cm proximal to the dilatation of the carotid bulb. The linear array transducer generates a measurement of the IMT and displays it on the screen with a percentage success of the procedure, ranging from <50% success to 100%. For this study, the percentage success of >95% was used. The same procedure is done for each side and the mean of right and left common carotid IMT was calculated.

The presence of plaques was defined as localized echogenic structures encroaching into the vessel lumen, for which the distance between the media adventitia interface and the internal side of the lesion was ≥1.2 mm.[5] IMT was measured in the plaque-free areas and measurements were carried out on both sides.

Laboratory tests

Serum creatinine, urea, lipids, complete blood count and urinary protein quantification were done at the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) as part of the routine tests for the standard of care of patients at the kidney transplant clinic. All samples for serum chemistry were analyzed using ADVIA® Chemistry Systems (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc).

Serum creatinine was measured using the modified Jaffe method. The normal range for males is 62-106 mmol/l and for females is 44–80 mmol/l at the NHLS laboratory.

Serum cholesterol and triglycerides were determined using enzymatic colorimetric methods. The triglyceride concentration was measured based on the Fossati three-step enzymatic reaction with a Trinder endpoint. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol was measured after precipitation of the non-HDL fraction with phosphotungstate-magnesium, while low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol was estimated indirectly by the use of Friedewald formula; LDL cholesterol = total cholesterol − (HDL cholesterol + triglycerides/5).

Complete blood count was done using automated hematology analyzer (ADVIA 2120® Philips Corporation, USA). This formed part of routine tests done at every clinical visit.

For 24 h urine protein excretion, the ratio of the urinary protein excretion in mg/dl to that of urinary creatinine in mg/dl from a spot urine sample was used. Spot urine protein to creatinine ratio has been validated as a better test than 24 h urinary protein quantification; it is not affected by urine volume or concentration, whereas the latter is prone to errors of collection and it is inconvenient to the patient and laboratory staff.[6]

All data obtained were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science for windows software (SPSS), version 17. Chicago: SPSS Inc. Quantitative data were reported as mean ± standard deviation. Differences in means for continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test while categorical variables were compared using Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests as appropriate.

Results

Among the 100 KTRs studied, 63 were males (63%) and 37 were females (37%). The mean age of the study population was 42.2 ± 12.42 years with a range of 19-70 years. Ninety-five (95%) had primary transplants while 5 (5%) had second transplants. Mean duration of follow-up was 60 ± 18.8 (range 36–89) months. Immunosuppression was calcineurin inhibitor based, with 44% on tacrolimus, 34% on cyclosporine, 19% on mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor and 3% on leflunomide. All but one KTR were on low dose steroid (5 mg daily) in addition to mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. There were 31 biopsy-proven rejection episodes, of which 26 were due to acute cell-mediated rejections, 4 were acute humoral rejections and 1 was combined cell mediated and humoral.

The mean BMI and waist circumference of the recipients were 26.4 ± 4.81 kg/m2 and 90.73 ± 14.76 cm, respectively; males had mean BMI of 26.21 ± 4.2 while females had mean BMI of 26.72 ± 5.66; P = 0.609. Twenty-nine patients were obese; of these, 24 (82.8%) had moderate obesity, 4 (13.8%) had severe obesity while 1 (3.4%) had morbid obesity. Obese KTRs had graft dysfunction (P = 0.033), they were however not different from their non-obese counterparts in terms of gender (P = 0.586), diabetes status (P = 0.549), levels of physical exercise (P = 0.567), rejection episodes (P = 0.351) or smoking status (P = 0.807). Graft function was similar between KTRs who smoked and those who did not (P = 0.15).

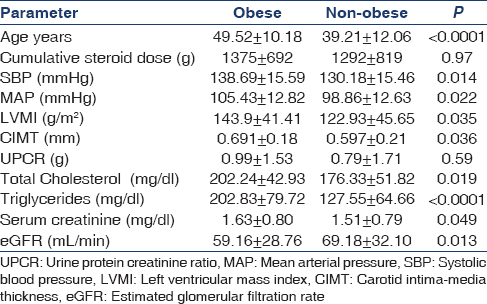

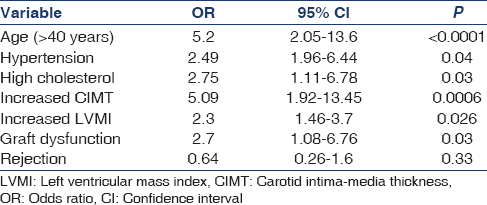

Table 1 shows the clinical and laboratory characteristics of the study population. Association of obesity with age, BP, left ventricular hypertrophy, rejection, increased carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT) and total cholesterol is shown in Table 2.

Logistic regression showed obesity to be independently associated with graft dysfunction (P = 0.036).

Discussion

This is the first study documenting cardio-metabolic risks and atherosclerosis in KTRs in sub-Saharan Africa. The recipients were all those attending a public hospital transplant facility serving the lower socio-economic sector of the population, especially those without health insurance.

Prevalence of obesity in this study was high, similar to that reported in other studies.[1234] Obese KTRs had higher BPs in our cohort; Armstrong et al. in a Canadian study[2] found SBP, proteinuria progression, fasting blood glucose and lipid disorders to be significantly higher among obese KTRs. Bardonnaud et al.[3] however, found no difference between obese and normal weight KTRs in terms of BP, graft and patient survival.[3]

Female gender, black race and low socioeconomic status were found to be risk factors for obesity in one large study.[7] In our study, the prevalence of obesity was similar between male and female KTRs; this could be due to the small sample size in this study. Blacks constituted over 85% of our KTRs; thus, comparison of racial differences in obesity would be inappropriate in our study subjects. We did not assess socioeconomic status in this study.

Obese KTRs were older in this study; the same observation was made by Kovesdy et al. in a prospective study of 993 KTRs[4] and also by Bardonnaud et al.[3] It appears that as the KTRs advance in age, the tendency to become obese also increases.

Obese KTRs are more likely to have lipid abnormalities, higher left ventricular mass index and thicker carotid intima-media. Obese KTRs were not different from normal weight KTRs in terms of proteinuria and levels of physical exercise; they were also not different in terms of cumulative steroid dose, incidence of diabetes mellitus, rejection episodes and smoking habit. Moreira et al.[8] reported higher incidence of new-onset diabetes after transplant in obese recipients, contrary to our findings. Mean serum creatinine and GFR were significantly different between obese and non-obese KTRs; obesity was independently associated with graft dysfunction in our study. Obesity was associated with high BP, high serum lipids and cIMT, similar to other reports.[4910]

Obesity is prevalent among KTRs in South Africa, and it is associated with graft dysfunction and markers of atherosclerosis. Further longitudinal studies with a large sample size are needed to fully ascertain the relative contribution of several documented risk factors for obesity and the impact of the intervention in our South African KTRs.

The limitation of this study was the small sample size and the fact that pre-transplant BMI was not documented, hence the assumption that all the obese KTRs only became obese in the post-transplant period; however, potential recipients were only listed for renal transplantation if their BMI was <30 kg/m2.

We wish to acknowledge the contributions of Prof. Russel Britz and Dr. Ben Wambugu of the Divisions of Vascular Surgery and Nephrology, respectively, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Relation between steroid dose, body composition and physical activity in renal transplant patients. Transplantation. 2000;69:1591-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obesity is associated with worsening cardiovascular risk factor profiles and proteinuria progression in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2710-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcomes of renal transplantation in obese recipients. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2787-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Body mass index, waist circumference and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:2644-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Methodological considerations of ultrasound measurement of carotid artery intima-media thickness and lumen diameter. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2007;27:341-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of patterns of proteinuria on renal allograft function and survival: A prospective cohort study. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:E297-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Variables affecting weight gain in renal transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:349-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obesity in kidney transplant recipients: Association with decline in glomerular filtration rate. Ren Fail. 2013;35:1199-203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Obesity and cardiac risk after kidney transplantation: Experience at one center and comprehensive literature review. Transplantation. 2008;86:303-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of body mass index on renal transplant outcomes: A significant independent risk factor for graft failure and patient death. Transplantation. 2002;73:70-4.

- [Google Scholar]