Translate this page into:

Chromoblastomycosis in a renal allograft recipient

Address for correspondence: Dr. Yesudas Santhakumari Sooraj, Nephrology and Poisoning Services, PVS Memorial Hospital, Kaloor, Kochi - 682 017, India. E-mail: drsooraj@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Medknow Publications & Media Pvt Ltd and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

A 50-year-old lady presented with a progressive ulcero-proliferative lesion over the right heel for over 1 month. She was diagnosed with end-stage kidney disease 18 months earlier and had undergone a successful live-related renal transplantation 12 months ago. She was on prednisolone, cyclosporine, and mycophenolate mofetil. Ten months later, she developed severe allograft dysfunction, and renal allograft biopsy revealed acute humoral rejection. She was treated with dialysis, plasmapheresis, and rituximab. Cyclosporine was replaced with tacrolimus. Her allograft function improved but did not reach the baseline.

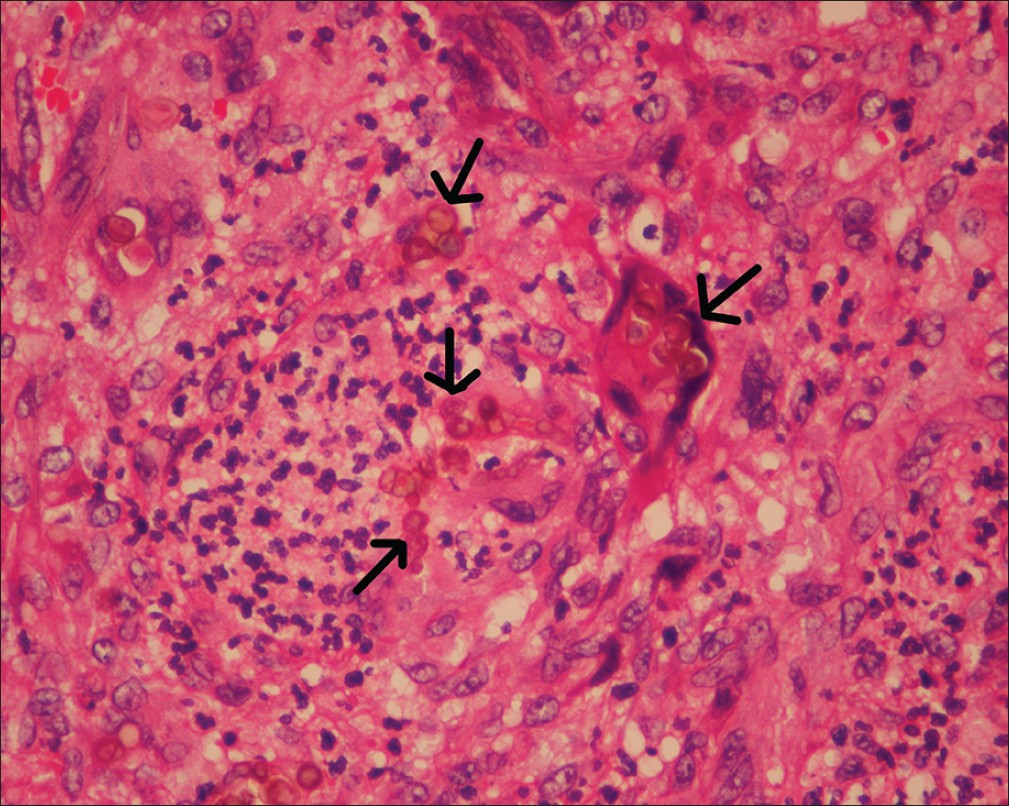

Clinical evaluation revealed an ulcero-proliferative lesion measuring 2 × 1.5 × 0.3 cm. The lesion was completely excised. Sections from skin epidermis showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and an area of ulceration with a sinus tract. Exocytosis of neutrophils with microabscesses was also noted. There was marked ballooning degeneration in the upper layers of the epidermis. Dermis showed dense lichenoid granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate. Multiple small abscesses composed predominantly of neutrophils admixed with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils were seen. Numerous giant cells containing multiple brown-pigmented, ovoid, thick-walled, sclerotic/copper-penny/Medlar bodies were observed, singly scattered and in chain-like clusters. There was no budding and many of the sclerotic bodies showed septations [Figure 1]. These were characteristic of chromoblastomycosis.

- Light microscopy (× 40, magnification) showing numerous giant cells containing multiple brown-pigmented, ovoid, thick-walled sclerotic/ copper-penny/Medlar bodies seen singly scattered and in chain-like clusters (arrows). These are characteristic of chromoblastomycosis

She was treated with oral itraconazole for a period of 4 weeks. There was no recurrence of the lesion and the wound has healed well.

Terra et al., first used the term chromoblastomycosis in cases of polymorphic fungal disease of the lower limbs presenting with nodules or verrucous plaques with hyperkeratosis and acanthosis of the affected epithelial tissues, which could develop into complications such as ulceration, lymphedema, and squamous cell carcinoma.[1] It is mainly caused by the fungal genera Fonsecaea, Phialophora, and Cladophialophora that are saprophytes in soil and plants.[2] The vast majority of cases are attributed to Fonsecaea pedroso.[3] The diagnosis is based on Potassium Hydroxide examination, identification of organism in histologic sections, culture of the organism that reveals slow-growing green to black colonies, and microscopic appearance of the conidia formation, which helps in identifying the species.[4] Medlar bodies seen in either pathologic or microbiologic examinations are diagnostic. They are defined as rounded, brown structures, 5–10 mm in diameter, with thick walls and internal septations.[5]

The characteristic lesion is the warty papule or plaque. The disease spreads to the adjacent skin by forming satellite nodules. Metastatic spread to other organs is very rare.[6] Few cases have been reported from India also[78] and this is the second case to be reported among renal allograft recipients.[9]

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Novo tipo de dermatite verrucosa: Micose por Acrotheca com associação de leishmaniose. Bras Med. 1922;36:363-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromoblastomycosis: Clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and therapy of infections caused by dematiaceous fungi. J Chemother. 2003;15:36-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromoblastomycosis and related infections: New concepts, differential diagnosis, and nomenclatorial implications. Int J Dermatol. 1975;14:27-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromoblastomycosis in sub-tropical regions of India. Mycopathologia. 2010;169:381-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in a renal transplant recipient: A case report and review of the literature. Am J Kidney Dis. 1996;28:137-9.

- [Google Scholar]